An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 90 (of 95 parts) - Bold Colliery Part 1 (1875 - 1955)

Photo Album 1 | Photo Album 2 | Photo Album 3 | Photo Album 4

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me

Photo Album 1 | Album 2 | Album 3 | Album 4

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

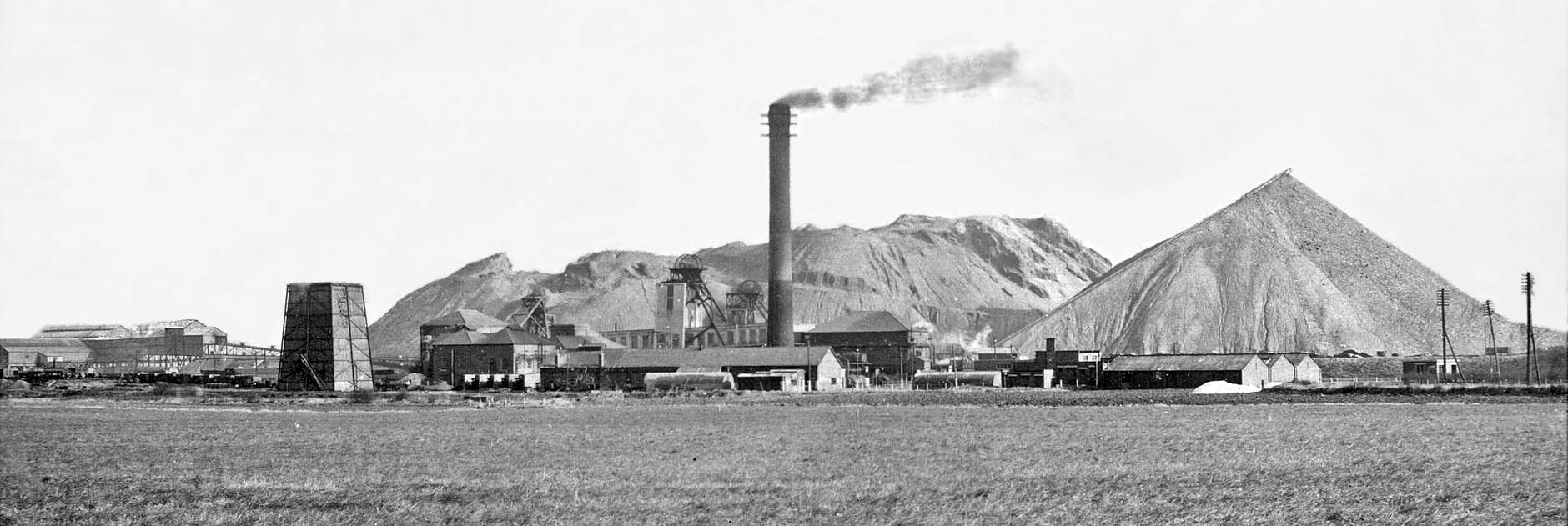

An early 20th century photograph of Bold Colliery which had its first shafts sunk in the 1870s and closed in 1986

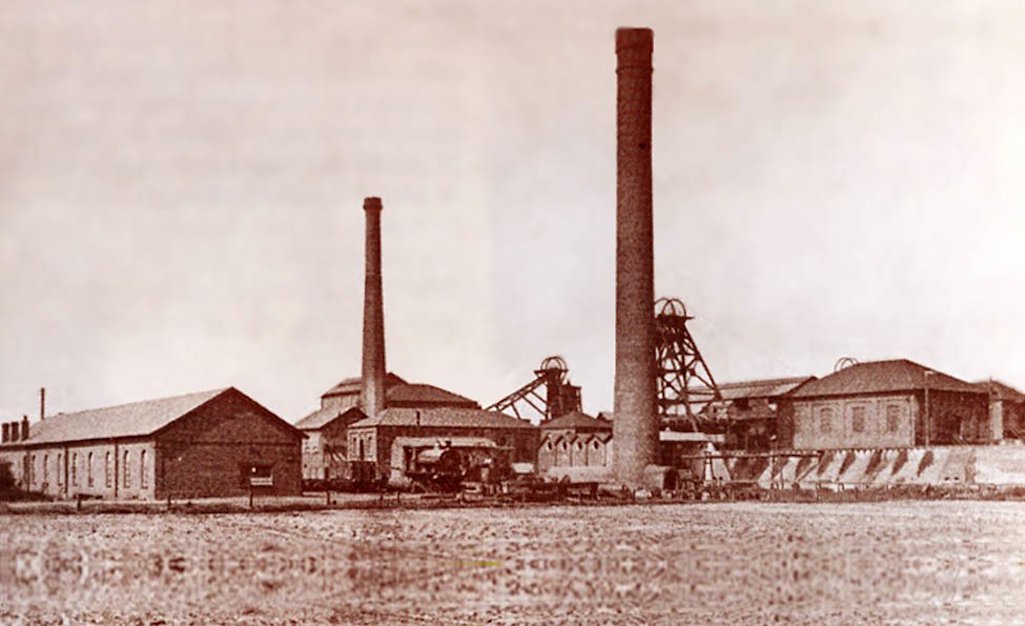

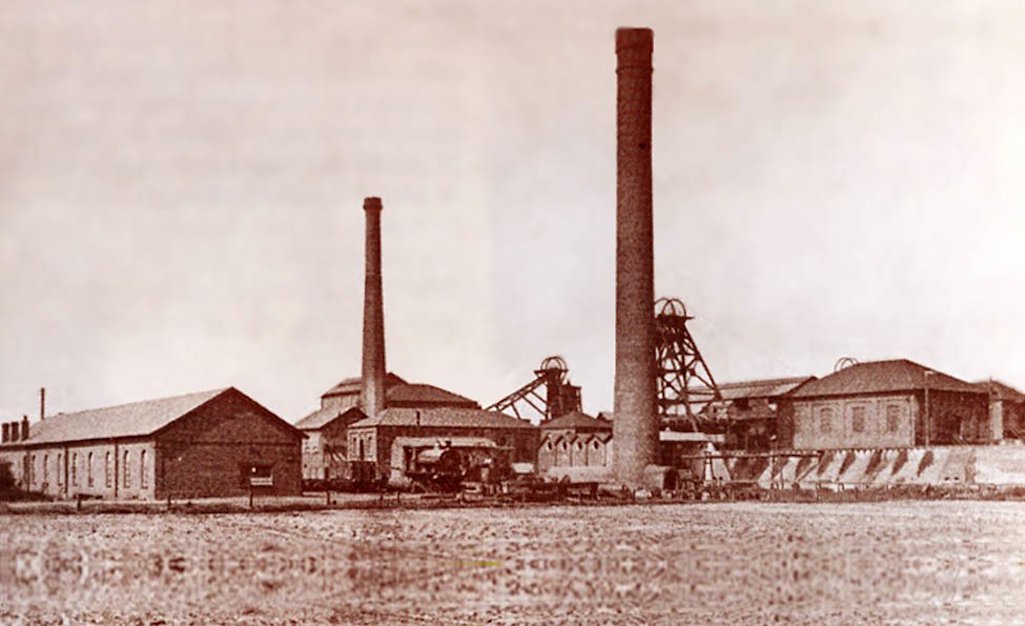

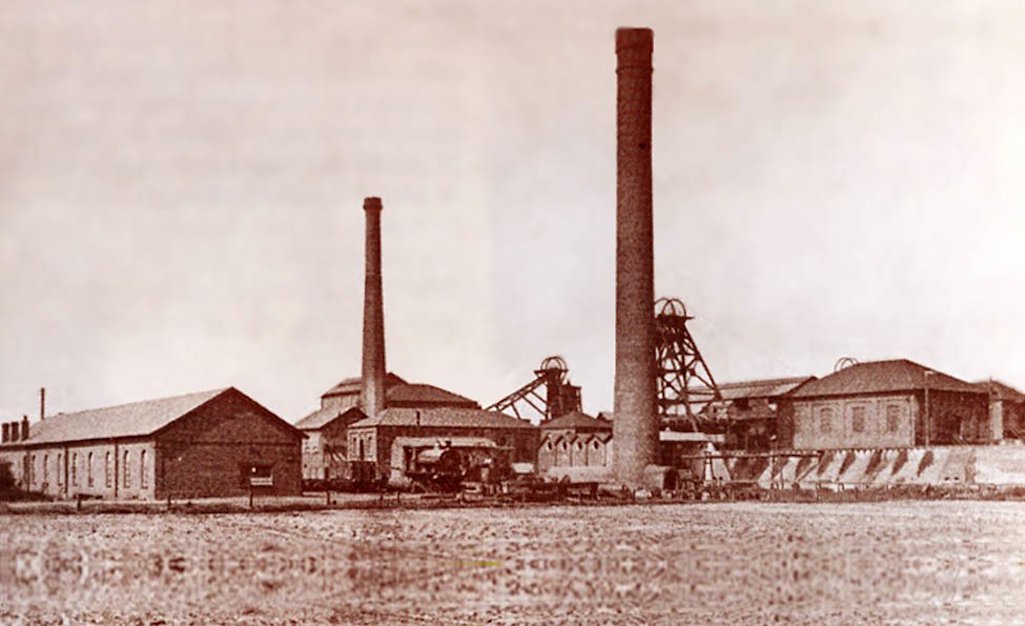

An early 20th century photograph of Bold Colliery

An early photograph of Bold Colliery

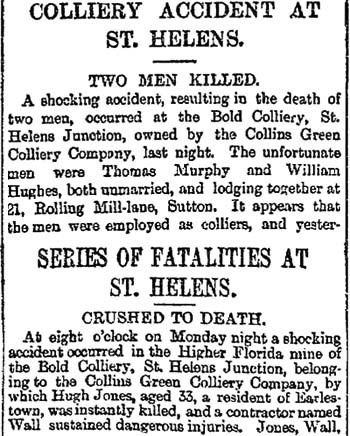

By 1875, no.1 shaft with a diameter of 12 feet had been sunk to 607 yards and no.2 shaft with a diameter of 16ft 6 inches had been sunk 200 yards. Later that year after £57,000 had been spent, operations were abandoned due to flooding. However, in 1878 the Collins Green Colliery Company bought the plant and extended the no.2 shaft to match no.1's depth of 607 yards. On January 23rd 1886, 18-years-old William Yates was killed when installing a heavy bar. He was working with his father when a prop suddenly gave way and the bar struck him on his head. A few days later, 35-year-old Dominic Dalton died after entering a cage to remove loaded tubs. The engine accidentally lifted the cage eight feet and although Dalton, the pit banksman, was able to leap out, a tub of coal fell on top of him.

Bold Colliery miner pictured c.1900

The Collins Green Company were back in court on April 4th 1887 when they were prosecuted for storing 48 lbs. of dynamite and 51 lbs. of blasting cartridges within unlicensed places in Bold Colliery. Their gunpowder store was also said to have been very dirty when inspected, with iron hooks and brass cans lying about. The company initially put the blame on their former storekeeper, telling the court that he should have been summoned not them. Then they said it was the fault of a Mr. Pygott who had sunk the shaft eight months previously and left dynamite behind. However the sinker took the stand and claimed he had not used dynamite, nor left any behind. The magistrates said the case demonstrated an 'utter want of care and supervision' and imposed the full penalty on the company that the law allowed, which amounted to £4 10s. plus costs. The company had previously been fined 60 shillings in 1884 for keeping gunpowder in an unauthorised place.

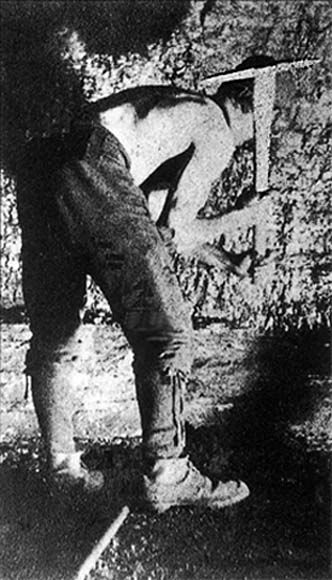

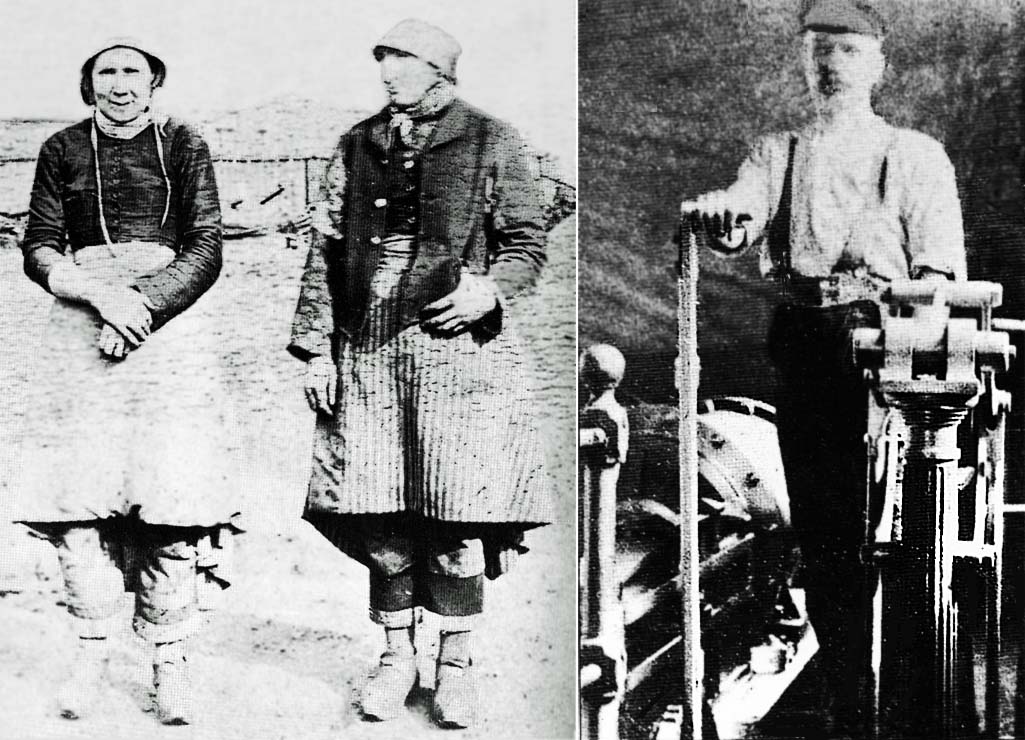

Two ‘pit brow lasses’ who worked in the Bold Colliery screenings and an engine man - both photos taken around 1900

Two pit brow lasses at Bold Colliery and an engine man c.1900

Pit Brow lasses and engine man c.1900

Then on February 11th 1888 William Storey endured a dreadful death at Bold Colliery. The 45-year-old was a blacksmith and was helping to install a new pit cage. The work was almost finished when the foreman William Holmes asked Storey to pass him some shackles. He should have walked round the outside of the cage to hand them to his boss. But instead Storey went across the front, missed his footing and fell between the cage and the side of the pit. Storey was hurled 600 yards to the bottom of the shaft, smashing through a scaffolding of three-inch planks and finally landing in 20 feet of water. It took four hours to recover his body and bring it to the surface. The Liverpool Mercury said it “presented a most shocking appearance”.

During the afternoon of Thursday 16th October 1890, 36-year-old Robert Lewis of 414 Watery Lane, Sutton was crushed by a stone that fell on his back from the pit roof. He was taken to his home and died at midnight. His inquest was held at the Vulcan Inn the following Monday where no blame was apportioned. Mr. Hall, the government inspector, had found the place where the accident happened had been well timbered with props. This wasn't always the case with insufficient supports costing the lives of a number of men at Bold and at 8pm on November 10th 1890, 33-years-old tunneller Hugh Jones was instantly killed by a roof fall and another man severely injured.

In 1890 the sinking of shaft no. 3 began and this was completed to a depth of 617 yards by 1892. By that year, the height of the headgears for all three shafts was recorded as being 60 feet and it was also stated that the Collins Green Colliery Company had constructed 100 workers' cottages at Burtonwood with 54 more being built. A social club had also been established which had 100 members of which the Colliery Guardian said 'Every endeavour is made to provide means of recreation and to give interest and employment to the mind'.

Health and safety during the nineteenth century was, of course, nowhere near as strict as today. However, there were certain rules that had to obeyed and smoking or drinking were taboo. In April 1891, Richard Houghton, John Riley and a man called Tickle were each fined between five and 40 shillings for drinking in the engine house at Bold colliery.

Then on April 12th 1892 Richard Clare appeared in St.Helens Police Court charged with breaching the Coal Mines Regulation Act. He was accused of getting into the cage at the bottom of no. 2 shaft when the full complement of twelve men had been reached. Clare refused to get out and after five minutes hooker-on James Yates felt obliged to signal the cage up, allegedly jeopardising the safety of the men. The collier from Sutton was defended by feisty solicitor Henry Riley who argued that the prosecution was instigated because his client was a trade union activist. Riley also argued that all 13 men had technically breached the law and Clare shouldn't be singled out. Enoch Woods gave evidence that there was a lack of discipline when getting into the cage and he and fellow collier John Leyton agreed with Clare's assertion that he had been seventh in order but had been pushed out of the way. The magistrates fined Richard Clare half a crown plus costs.

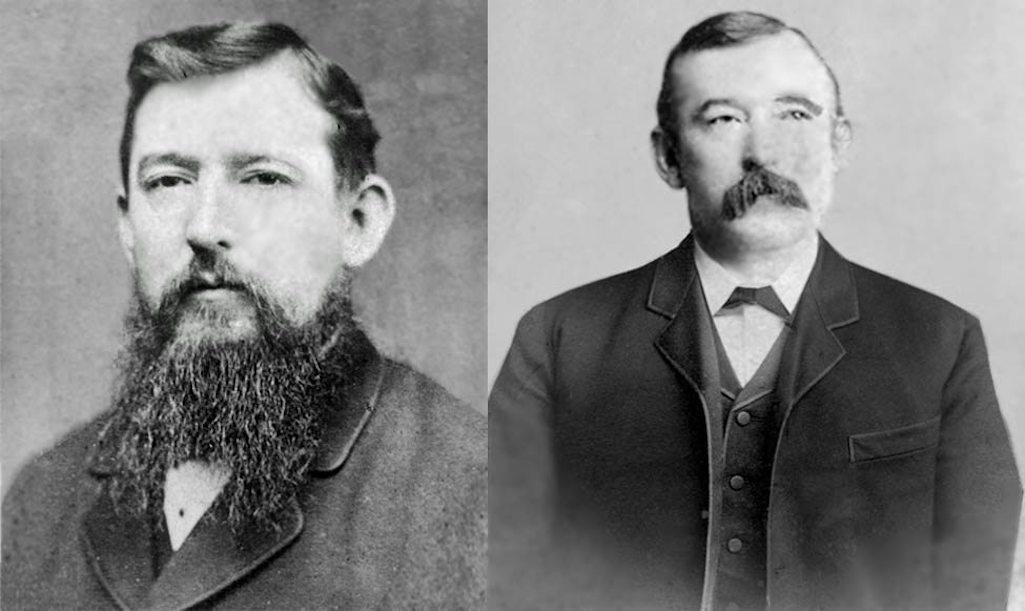

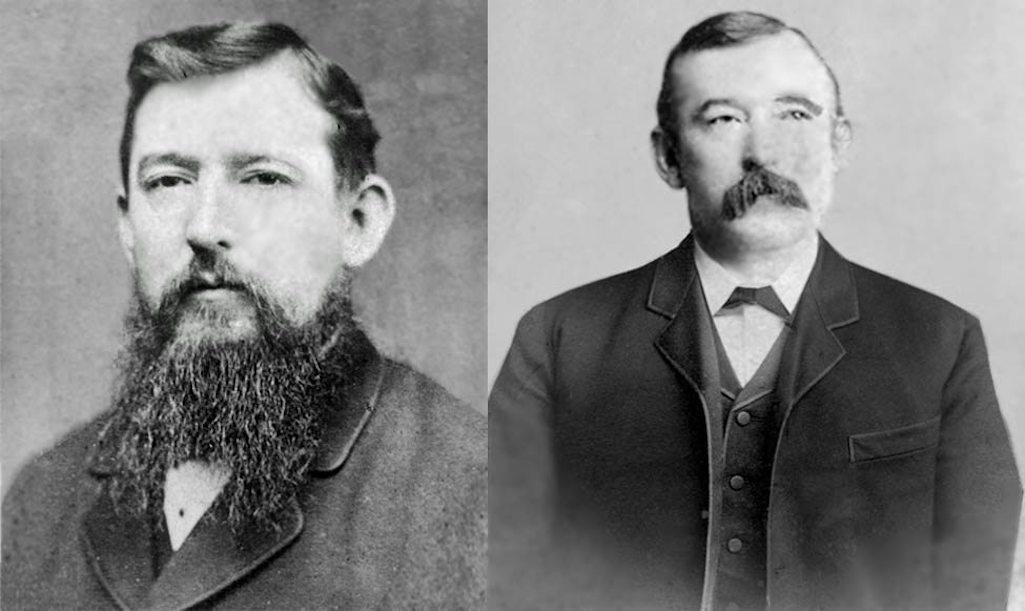

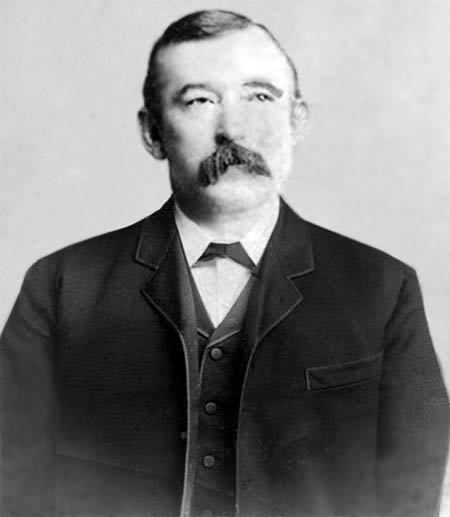

Two pictures of Andrew Jackson who was an early manager of Bold Colliery - contributed by Martin Heys

Two pictures of Andrew Jackson who was an early manager of Bold Colliery

Bold manager Andrew Jackson

Many mineworkers received serious injuries which, although not life-threatening, could have fatal consequences. In October 1892, 48-years-old labourer Joseph Grice of Hills Moss Road, Sutton was injured at Bold and was unable to return to work. Consequently he became very depressed and on August 21st 1893 he took his own life in a pit of water near his home. Grice had used handkerchiefs to bind his body and left a widow and seven children.

The number of boys who sacrificed their lives at the colliery was especially tragic. On January 9th 1893, 15-years-old Edward Parry became the second youngster to be killed at Bold colliery. He was the son of collier William Parry of 5 Rolling Mill Lane, Sutton and they were working together in the Florida Mine when a large stone detached itself from the roof and struck Edward. A similar tragedy occurred on November 23rd 1894 when 43-years-old packer John Griffith was crushed by a stone from the roof.

There was no production at Bold for several months during 1893, as a result of a strike that affected all Lancashire and Yorkshire pits. It was caused by the owners cutting wages by 25% to compensate for a drop in the market price of coal. Although the unions gave permission for men to carry out important maintenance and safety work, this didn't always go down well with firebrands such as William Jackson. He was a Barnsley miner who came to St Helens in June of 1893 and on August 30th he led 200 miners, women and boys to Bold colliery. They were met by manager Andrew Jackson who insisted that no coal had been wound since the strike had begun.

The sixteen men who were keeping the pit in good order were brought to the surface and warned by the strikers not to to undertake any work in future. Jackson also led strikers to Lea Green and Ashton's Green collieries and was given the nicknames 'Leader' and 'Agent'. On September 23rd 1893, William Jackson was sent to prison for two months for smashing 11 panes of glass in a cobbler's shop in Worsley Brow after a dispute (details here).

It took two hours to dig out Hughes's body as the fall of stones had been so great. The two friends had only started working at Bold some three or four days earlier and at their inquest, the jury and coroner called for a legal requirement for officials to visit work persons more than once during each shift. Coroner Sam Brighouse pointed out the large number of fatalities through roof falls and how the law only required employers to make timber available to the miners so they could prop up roofs. The obligation was on the worker to keep himself safe and not the employer.

Three months later on December 6th, 28-years-old William Jones of 13 Junction Lane was killed by another roof fall while creating a roadway down the mine. Then on May 27th 1896, John Smallshaw, the 48-years-old surface manager at Bold colliery, died in St.Helens Hospital from injuries sustained nine days earlier. Smallshaw, who lived at Bold Villas at St.Helens Junction, had been inspecting a new engine house when he missed his foothold and fell eighteen feet. He landed on his head and also damaged his spine. On January 3rd 1896, 40-years-old day wageman John Jones was crushed to death by a roof fall and on May 1st of that year, 50-years-old engine wright John Smallshaw was fatally injured after he'd fallen while working on a new fan house.

By now the Collins Green Colliery Company were taking a more proactive approach to health and safety and on March 9th 1897 it took three of its own workers to court for separate breaches of its rules. Shot lighter William Cartledge of Mansfield Street, Sutton, was summoned for not putting up a danger board and fencing off an area. This was after a 'shot' - an electrically-triggered high explosive - had misfired on January 12th. For that he was fined £2 in the St.Helens Police Court. Some time later an accident occurred when Robert Jones attempted to unram the misfired shot and he was very badly injured. Despite his injuries, Jones was prosecuted as a warning to others and fined £1. Robert Hughes of Watery Lane was also summoned for having matches down Bold Colliery and he was fined £1.

On June 27th 1898, fifteen men were seriously injured when the cage in no.3 pit crashed into a wooden platform at the bottom of the shaft. The engine seemingly developed a fault and began operating at full speed which led to the ascending cage getting stuck in the headgear. On July 20th, collier Edward Hewitt had his right arm amputated after an accident with a box. When he later made a claim under the Workman's Compensation Act, the Collins Green Colliery Co. took out a summons against him that alleged he'd breached regulations. On November 2nd 1898, collier 48-years-old Samuel Jones of Penny Lane, Collins Green was killed in no.3 pit of Bold colliery by a stone of more than two tons that fell from the roof.

On February 20th 1899 there was a dreadful accident that cost three lives and left two men injured. The dead were 16-years-old James Thomason of Newton Road in Parr, 27-years-old William Donnellan and 23-years-old Philip Fogarty, both of Weymouth Street in Sutton. The tragedy was caused by a couple of wagons that broke loose from the endless rope haulage which then triggered a roof fall. Although help was quickly at hand, it took over an hour to extricate the three men who were all found to be dead. Their bodies were removed to the Clock Face Inn where an adjourned inquest was held. It continued in Farnsworth, where Mr. Hall, the government inspector commented that generally he did not feel that the colliery owners maintained a high standard of safety.

On Sunday May 7th 1899, 20-years-old Henry Rigby of 102, Normans Road, Sutton told his father John that he didn't want to go to work as he feared falling down the new shaft. On Monday the pumpman did exactly that, plummeting 75 feet into 12 feet of water and was dead when removed. He had been expected to work on a platform measuring 7 feet by 2 feet 6 inches with no safety fencing. At Rigby's inquest on the 12th, Mr. Matthews, the government inspector, recommended that a fence should be put around the platform, which was a bit too late for Henry Rigby.

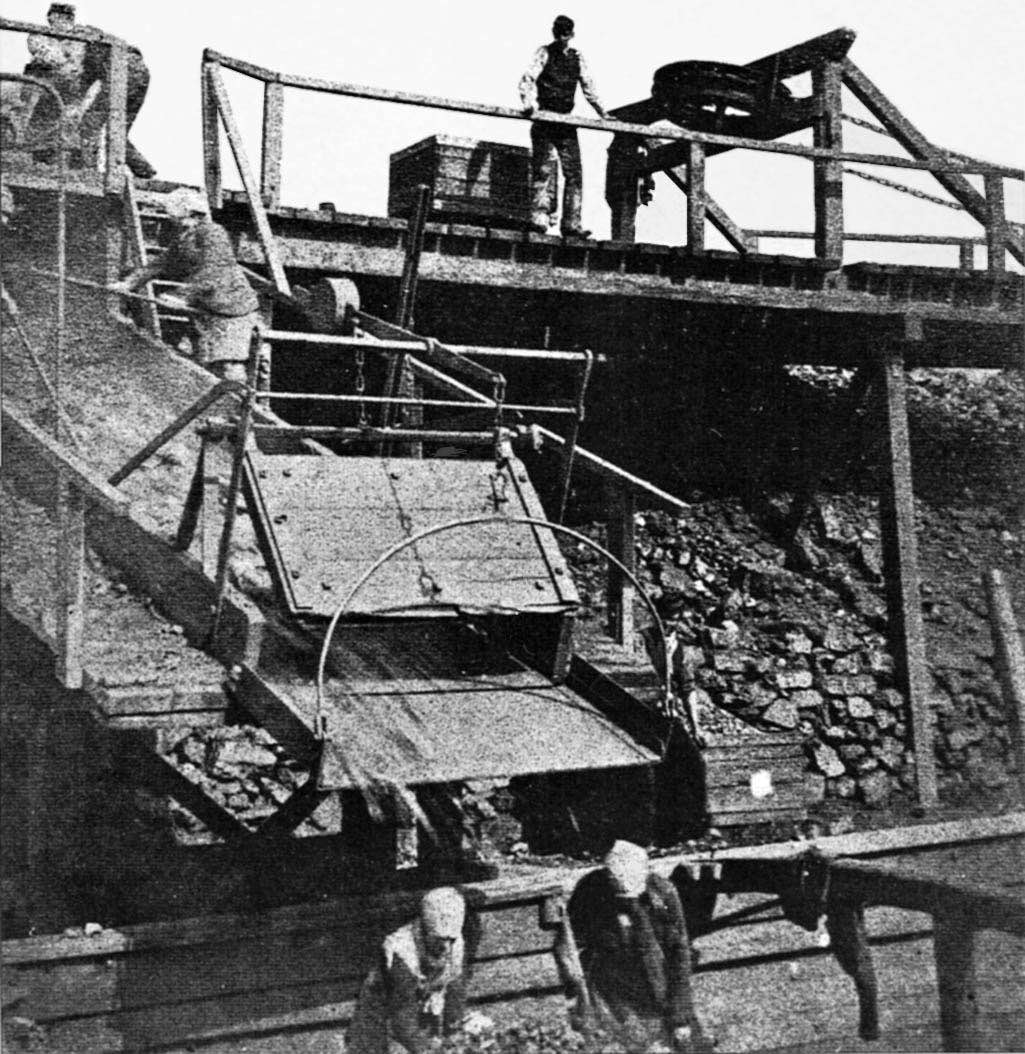

The pit bank haulage hand watches the operations below and would likely be shouting out instructions to the girls and those responsible for lowering the empty rail wagons down into position for filling, as well as moving the full ones away. A lever-operated door at the middle level could hold coal delivery to the conveyor back, if there were any problem below. It was normal to have up to three tippler/chute arrangements in place on pit banks to cover the various sized coal outputs and the girls would transfer over to suit the controller’s output requirements. The very primitive open to the weather elements of these activities would eventually lead to the coal buyers demanding a far better quality of supply and the introduction of high volume, more efficient, quality weather protected screening plants in the 1920s / 30s.

On March 22nd 1901, 22-years-old labourer William Blackmore, who lodged in Watery Lane, met with what one newspaper described as a 'terrible death'. He missed his footing when putting a large water tank into the cage and fell to the bottom of the 600-yards-deep shaft.

Then on February 10th 1902, 45-years-old John McGrath was crushed to death. On July 30th 1902, 33-years-old collier Joseph Jones of 5, Assam Street, Sutton was fatally crushed by a coal wagon. At the inquest into his death on August 1st, county coroner Samuel Brighouse threatened to jail colliery manager J. G. Thompson. Following his employers' instructions, Thompson had arranged for Jones's body to be removed to his home, which was outside of the township of Bold. Without the permission of a coroner, transferring a body between townships was illegal.

So Brighouse adjourned the inquiry for a fortnight demanding that Thompson apologise and provide an assurance that he will obey the coroner's orders in future. At the resumed inquest at the Railway Hotel in St.Helens Junction, it was revealed that a deal had been struck between the coroner and the Collins Green Colliery Company. In future when there was a death at Bold Colliery, the police would immediately summon a jury to examine the body. The deceased could then be removed to his own home and the coroner then contacted to schedule the formal inquest.

On January 20th 1903 in the no.3 pit, 26-years-old collier Charles Doherty was fatally injured when he was crushed against a wall. Two months later on March 19th, 31-years-old Joseph Horsley was killed when he was struck by a haulage rope after three tubs fell out of the cage and struck the rope. A fortnight later on April 4th, 24-years-old Robert Williams lost his life in no.2 pit when a stone fell on him. Then on June 14th 1903, four sinkers were badly hurt when an explosive 'shot' blew prematurely. The injured men included Patrick Coffey of Powell Street plus Martin Grace and Patrick Monaghan both from Herbert Street in Sutton. Exactly a year later, 26-years-old sinker Philip Lennon was fatally injured and on September 23rd 1904 an overturned tub killed 15-years-old pony driver James Jones of Frederick Street, Sutton.

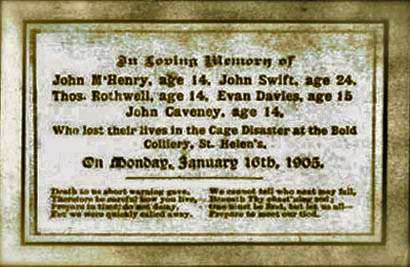

It was ironic that just 36 hours later, four boys and one man were killed and eighteen others were injured in the worst accident at Bold colliery. The cage in no.3 shaft, which carried eighteen males on two decks, was overwound by engine winder James Fowler who was coming to the end of a 13 hour shift. Instead of stopping, the cage sped down the shaft until it struck a platform that had been used in the recent sinking operations. It was fortuitous that it had been left there, as otherwise the cage occupants would have gone straight into 30 feet of water and all eighteen would have drowned.

The ascending cage went up into the headgear and the top of the engine house was demolished. Sutton's medical men, Dr. Bates and Dr. Casey plus Dr. Jackson and Dr. Tough arrived at Bold colliery as the fourteen injured men were brought to the surface. Nine were seriously hurt and they were taken by colliery ambulance and Dr. Bates’s car to St. Helens Hospital. The dead were John McHenry, Thomas Rothwell and John Caveney who were just 14-years-old, plus 15-years-old Evan Davies and 24-years-old John Swift. The inquest was held first at the Clock Face Inn before continuing at St.Helens Town Hall where no blame was attached to the unfortunate winder.

Within a few weeks of the tragedy, two more youngsters died at Bold colliery. These were 16-years-old James Smart from Marshalls Cross and 17-years-old James Monaghan, both haulage hands. The pair were killed on February 20th in no. 3 pit by a large roof fall, despite the roof being well propped. It took half-an-hour of digging to get Smart's body out and a further two hours to retrieve Monaghan's. Then on April 17th 1905, 57-years-old collier Richard Dixon suffered internal injuries in no.3 pit. He was injured by falling against the tub that he was pushing and he died three days later.

On October 10th 1905 52-years-old collier William Taylor died at no. 2 pit when a stone from the roof fell on him. On January 31st 1906, 42-years-old packer James Rigby died in St. Helens hospital of blood poisoning after injuring his thumb two weeks earlier lifting a stone. Nine days later, 59-years-old collier Thomas Whalley was killed at the no. 3 pit after a roof fall. On June 7th Bold contractor Peter Healey was charged with shooting his wife with intent to murder her, after a row at their Burtonwood home.

One would have thought that lessons would have been learned after the terrible tragedy of January 1905 caused by overwound cages. However just 19 months later on August 25th 1906, a very similar event occurred within the same pit. Sixteen men were being sent down the shaft and sixteen men were being raised, when the two cages overshot their stopping points. This caused the rising cage to get hung in the head gear and the descending cage to strike the landing at the pit bottom with terrible force. Most of the men lived in the St.Helens Junction district and rumours spread like wildfire that all 16 in the descending cage had been killed. Amazingly it turned out that there had been no serious injuries, with just John Moran of 214 Reginald Road and John Doans of 57 Hoghton Road receiving minor injuries to their legs.

In November 1906, William John Carter of 70 Morris Street in Sutton died in hospital after being struck by a box that had gone off the rails. However, it was revealed at his inquest that he had an underlying medical condition, although his injuries accelerated his demise. On March 14th 1907, labourer, George Sharps, of 108 Herbert Street, Sutton, was run over by a locomotive. Six weeks later on April 26th in no.2 pit, 44-years-old collier David Leyland caught his knee with a pick. Blood poisoning set in but he continued working until May 7th and died a few days later. On September 5th 1907, 23-years-old drawer Joseph Fairhurst was fatally injured after being crushed in the no. 1 pit.

Then on December 15th 1907, 63-years-old Peter Ellison died in St.Helens Hospital from injuries received after being struck by a large stone. Yet another roof fall occurred on January 27th 1908 after an explosive 'shot' had been fired and 30-years-old contractor Patrick Regan was killed. On November 23rd 1909 St.Helens Fire Brigade spent several hours extinguishing a fire underground at Bold. They were not helped by having to obtain water from almost 800 yards away.

Tough miners would often continue to work after injuring themselves which sometimes cost them their lives. 35-years-old collier William Saxon slipped down a landing in the no.2 pit on May 18th 1910 and injured himself. He complained of pain in his leg and groin but carried on working until November when he died from a malignant tumour in the hip joint. On December 30th 1910, John Kearney, aged 29, died from the injuries he'd received in an accident six weeks earlier after he'd gone to pull up a sleeper to lay rails in a roadway.

The six-week long strike of 1912, which began at the end of February, was said to be the first national coal dispute and was centred on miners’ demands for a minimum wage. The Bold Colliery management refused to allow people to pick coal from the ‘stuff’ or spoil heap. Technically this was trespass and theft but it could also be dangerous. So on March 18th an angry crowd of 400 gathered at the colliery and had to be driven away by the police. The crowd tore up some fencing before moving onto Collins Green Colliery where they broke windows and threw stones at police.

On June 27th 1912, Samuel Copeland, a 16-years-old haulage hand, was killed in the no.1 pit at Bold when 10 tons of metal fell on top of him. 70-years-old brow hand Louis Helsby was killed on March 20th 1913 (possibly 1923) when he fell 22 feet as he attempted to lift a tub. Then John Mather, an 18-years-old haulage hand, was crushed to death against the roof on May 10th 1913.

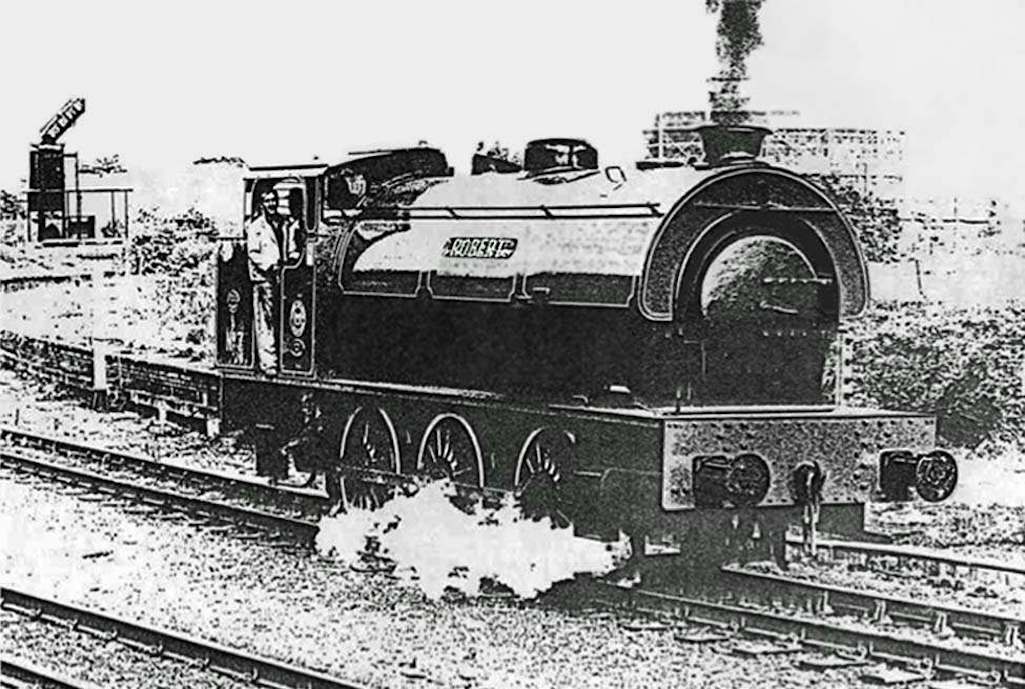

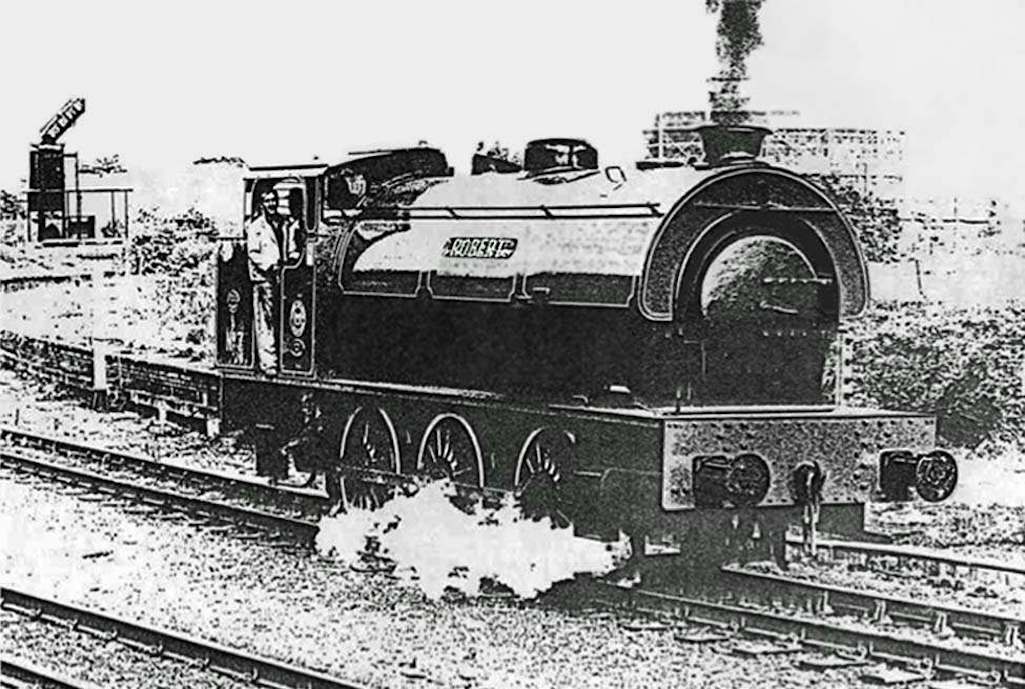

Robert one of three locos at Bold Colliery from Frank Bamber's Round About The Pits

Robert one of 3 locos at Bold - from Frank Bamber's Round About The Pits

The loco Robert at Bold Colliery

The long list of casualties at Bold continued in 1915 when on April 27th, 48-years-old Edward Morgan of 53 Helena Road died on his way to St.Helens Hospital after being struck by a stone that measured 7 feet by 5 feet. His two sons were working on the surface when the accident happened. A large stone also saw off 24-years-old packer James Golden at the colliery on July 30th 1915. Sometimes it took months before pit men succumbed to their injuries. 46-years-old Moses Billinge of 19 Watery Lane suffered spinal injuries at Bold on March 22nd 1915 when crushed by full boxes landing on him. However he didn't die of his injuries until mid-August.

Griffith Roberts of 33 Eliza Street in Sutton met a shocking death on December 11th 1915. The 20-years-old had reached over to attend to a leaking steam tap and caught his clothing in a shaft revolving at 100 revolutions per minute. He was carried round and round and the top of his head was torn off. Albert Jelley was killed by a roof fall on March 15th 1916. The latter lived at 18 Powell Street in Sutton but had curiously been employed at Bold under the name of Thomas Kelly. The coroner's jury at the Clock Face Hotel were in the process of signing their verdict of 'Accidental Death' after completing their inquiry into Kelly's death when William Jelley hurried into the room. He stated that his brother's real name was Albert Jelley and the coroner had to change all the paperwork.

Then on June 26th 1916, 34-years-old Edward Davies of Tickle Street in Parr badly damaged his spine at Bold, from which he died a week later. On December 16th 1916, 16-years-old Fred Hilton of Burtonwood was crushed between boxes of coal. However, he failed to report the accident and went home telling his parents that his legs hurt. Hilton didn't seek medical attention until two days later and shortly afterwards died in hospital from blood poisoning.

Boys were not paid well for their arduous work down the pit. Robert Heyes began working at Bold Colliery about 1912 when aged 11 or 12. Like other youngsters he was in charge of the tubs and his first wage packet was just a few shillings for over 50 hours labour. To supplement his meagre wages Robert was forced to dance on pub tables. Understandably he became a communist and after moving to Doncaster after the 1926 strike was badly injured and broke his back.

The word 'crushed' is synonymous with the perils of mining and 22-years-old Edward Roughley fractured his spine after a fall of stone on January 16th 1920, dying five weeks later in hospital. He had served in the St Helens 'Pals' from 1915 to February 1919 only receiving a slight arm wound. It took a return to mining at Bold, just six months before the accident, to see him off.

In St Helens County Court on November 12th 1919 miner James Meadows sued the owners of Bold Colliery for £1 9s 8d, which was two days wages. In September, Henry Blacker, the under-manager at the pit claimed he saw Meadows using the haulage road to get to his underground workplace rather than the travelling road. The latter was a safe pathway for the mineworkers to get to their designated coalface, while the haulage road was used to transport full and empty coal tubs. It was a more direct route but could be dangerous and many miners had died after being struck down by tubs.

Blacker said Meadows had been with other men on the haulage road and when they saw him they had all run away. Sometime later the under-manager told James Meadows that running away was not a wise thing to do, as you "would likely have your brains knocked out". Using the haulage road was against the colliery rules and Meadows was told he would have to pay a fine of 2/6 and sign a document, which the miner refused to do.

He was then sacked but after two days of discussions between miners' representatives and management the fine was rescinded and Meadows was reinstated. However the man wanted his two days' pay while the dispute was being settled – hence the court case. The under-manager swore positively that he had seen and heard Meadows on the haulage road. However the lighting was poor and the miner had three witnesses in support and so the judge awarded him his full claim of £1 9s 8d.

A double tragedy occurred at Bold Colliery at 4:45am on May 31st 1920 when two men from Burtonwood were killed. They were Thomas McNicholas from Fairclough Street and John Mullin from Mercer Street. Both men were working underground alongside Patrick Burns installing a supporting prop to the pit roof. Suddenly without warning the roof gave way, trapping Burns under debris for ten minutes. He suffered injuries to his right leg but got off lightly as McNicholas and Mullin were instantly killed. Their bodies were taken to the Clock Face Hotel, where most inquests in the district were held. On August 13th 1920 John Donegan of Islands Brow in St Helens was killed down No. 2 pit of Bold Colliery after a roof fall. He left a widow and seven children.

Around midnight on February 16th 1921, fireman Henry Worthington and John Prescott died at Bold as a result of yet another roof fall. The inquest into the double tragedy took place at the Clock Face Hotel two days later. A number of men had been working at midnight inside a new tunnel when the roof collapsed. John Prescott was struck by a large stone and was covered in debris, with only his head visible. At that point the 44-year-old from Westfield Street in St Helens was still conscious and he shouted, "Get me out", to James Barnes, who went to his rescue.

Once the underground roof had been weakened by a fall of stone and dirt, it was common for further falls to occur. While Barnes and fireman Henry Worthington were attempting to free Prescott, a second drop took place and Worthington was badly crushed by falling stones. Barnes was also knocked down but eventually he managed to get clear and went for help. But before assistance could arrive, a third fall took place, which completely buried the two men and it was two hours before they could be extricated.

Bold Colliery's solicitor said at the inquest that 52-year-old Worthington of Garnet Street in Sutton had been: "…an old fireman and an official of many years' standing, and was highly esteemed; and the colliery officials and the men in the mine were deeply grieved that he should've lost his life when doing such a courageous act. With regard to Prescott it was hard lines that a man who had gone through the dangers and trials of the war should come here and meet such an untimely death. Worthington had, no doubt, given his life for his friends."

The cold statistics of mining accidents belie the family tragedies which had enormous personal as well as financial consequences for the widows and children. This photograph - contributed by James Prescott - was taken at the rear of 7 Garnet Street in happier times, with wife Mary Worthington standing at the rear by daughter Martha Prescott and her grandchildren (baby Edward with Jimmy, Marjorie & Harry Prescott.)

It was reported in a Mine Inspector’s Report of 1923 that three persons met their deaths at Bold while riding on tubs although no details are known. On June 5th, 1924, 60-years-old Ralph Thompson was killed by a roof fall that weighed about two tons and on September 27th 1924, Joseph Morris aged 50 years was killed by runaway boxes. Also in 1924, engineer John Webster went down the mine to remedy a problem but failed to allow his eyes to adjust to the dark and consequently walked into the spokes of return pulleys and was killed.

Surprisingly, the job of notifying relatives that a mineworker had met with a serious accident was not undertaken by senior management or by a police officer but by a boy apprentice. Frank Bamber was employed at Bold colliery from 1924 to 1942, initially as an apprentice joiner, and for three years was given that unpleasant task to undertake:

John (or William) Nicholson received fatal injuries at Bold on August 10th 1939 after a ‘shot’ had been fired. It was thought that the 54-year-old from Billinge had prematurely returned to the coal face from a place of safety, as two minutes had elapsed from the shot firer’s warning shouts to the detonation. As a consequence, procedure for shot firing at Bold was changed, with the firing of the shot taking place more quickly after the second and final warning.

As a result of the outbreak of war, it was reported in October 1939 that staff at Bold Colliery and the associated Collins Green Colliery were receiving an intensive series of anti-gas and first-aid lectures. The miners were used to the threat of gas underground but were now facing the possibility of being gassed above ground by the Nazis.

On October 16th Albert Gee was working down Bold when he heard a man shout that someone had been trapped by a roof fall. He dashed to the scene and discovered that the man was his brother James Gee of Holt Lane in Billinge. A large stone that was five feet long, a yard wide and eighteen inches thick, pinned down the 33-year-old, who died from his injuries three months later. An explosive ‘shot’ had been fired, which was believed to have loosened the pit roof, causing the stone to drop out.

The three seams at Bold colliery at this time were known as Crombouke, Higher Florida and Lower Florida. By the late 1930s they had been worked for such a considerable distance that the economic position of the colliery became difficult. At one point the colliery closed and in 1940 the Collins Green Colliery Company went into liquidation. However their assets were bought by the Sutton Heath and Lea Green Company, who redeveloped Bold and used the pits at Collins Green for pumping purposes. They began working a new seam of coal, called the Yard seam, and utilising deep-seam mining, which until recently had not been possible. As a result nos. 1 and 3 shafts were deepened to 918 yards and the Rushy Park horizon with diameters of 21 feet and 16 feet respectively. Bold became the outpost colliery in the direction of Warrington and new sidings were also laid, a new screening plant was built and tubs of a larger 15 cwt. capacity were introduced.

At the inquest into the death of 18-year-old haulage hand Joseph Barton on February 5th 1940, it was stated that hard hats were not compulsory at Bold and had to be purchased by the men. Barton was helping to get a derailed tub back onto the lines when a chain broke and struck him on the head. Colliery overman David Jones told the inquest that Barton was only wearing a beret at the time and the danger would have been lessened if he had worn a hard hat.

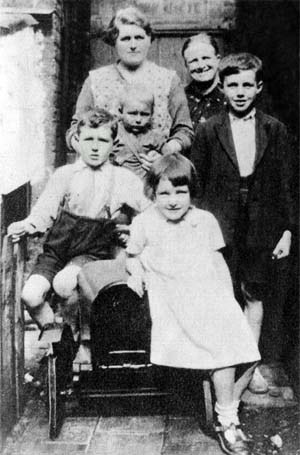

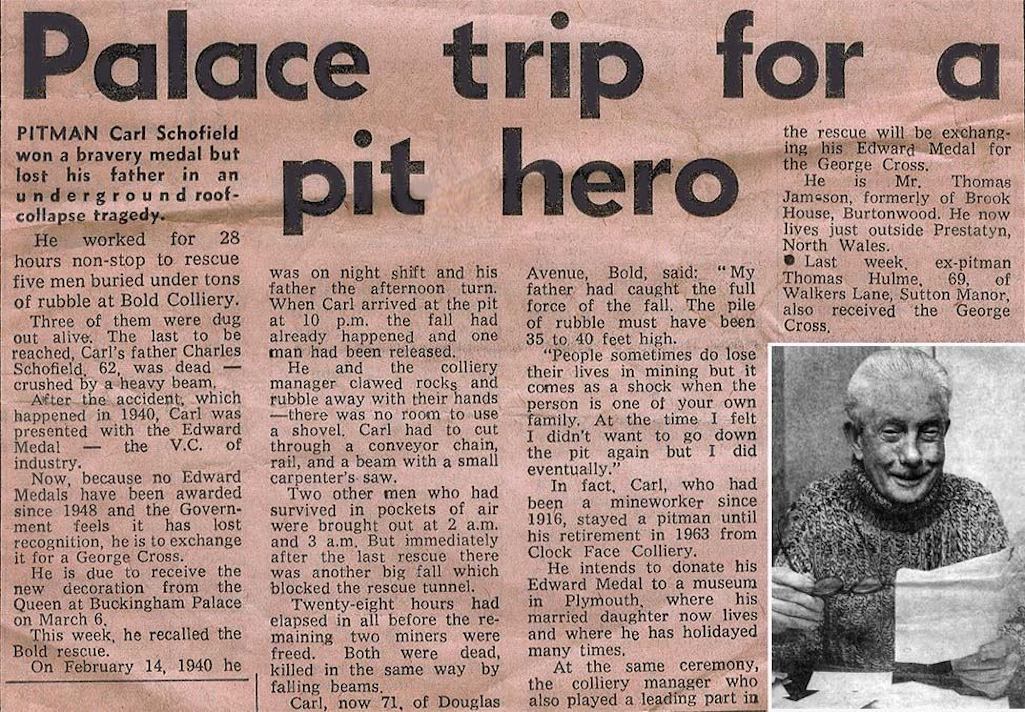

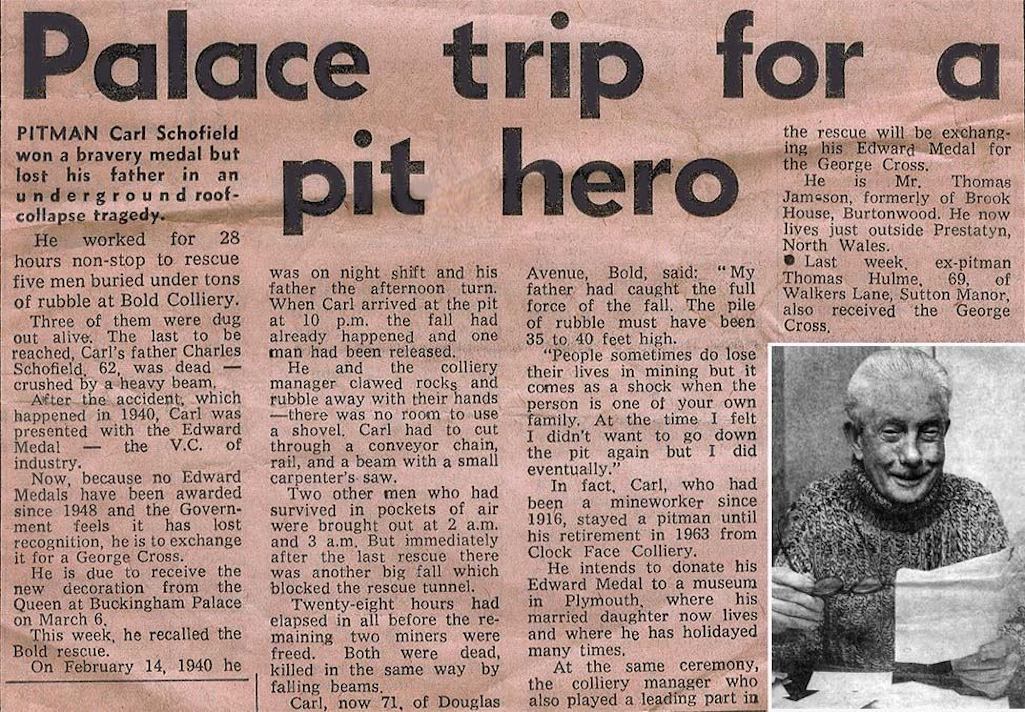

News cuttings from 1971 on Bold hero Carl Schofield - contributed by William Hancock

News cuttings from 1971 on Bold Colliery hero Carl Schofield

Cuttings from 1971 on Carl Schofield

Without warning a large section of roof collapsed upon them, injuring two of the men and completely burying the other five. Manager Thomas Jameson was at home but immediately went to Bold Colliery to take charge of the rescue operation. As Carl Schofield arrived at 10pm to begin his night shift, he learnt of the accident and immediately went to the scene. He realised that his father, who'd been on the afternoon shift, was likely to be one of the trapped men. Once fireman Ernest Hayes was freed he was able to tell the rescuers the approximate location of the other men.

Schofield and Jameson worked non-stop for 28 hours to rescue five men using their bare hands to remove rocks and rubble, as there was no room for a shovel. Speaking in 1971, Carl said the pile of rubble was 35 to 40 feet high. Using a small saw he cut through a conveyor chain, a rail and a beam and two men were brought out at 2am and 3am. There was then another fall that blocked the rescue tunnel. It took 28 hours to extricate the bodies of Carl's 62-years-old father Charles Schofield and 40-years-old Richard Shaw.

Carl had been a mineworker since 1916 and after his experience, he thought twice about going down the pit again. However he did eventually return to Bold and later transferred to Clock Face Colliery, where he worked until his retirement in 1963. Eight years later, Carl and Thomas Jameson were invited to Buckingham Palace to exchange their Edward Medals for the George Cross. Robert Mather, a haulage engine driver at Bold, was also honoured in 1951 when he was awarded the British Empire Medal.

Another fatal surface accident occurred on June 10th 1940, when 62-year-old John Porter of 62 Edgeworth Street was struck down by a waggon that was being shunted. The brakesman Frederick Hill was criticised at Porter’s inquest for riding on the engine with the driver instead of walking in front. Robert Phillips from Platt Bridge near Wigan, suffered a dreadful death at Bold in May 1941. The 17-year-old was found dead at the bottom of the shaft after apparently falling from the pit cage. There are not many reports of other accidents during this period, although on January 11th 1945, Charlie McCarthy, aged 56 from Collins Green, was fatally injured at Bold.

There was some industrial action at Bold Colliery during the war years over pay. It was part of a wider dispute in the Lancashire coalfield and took place on some days between December 1943 and February 1944. The so-called 'Porter Award' established a new national minimum wage but some felt it unfair with many anomalies. On January 31st 1944 the Daily Express reported how: 'After working half-naked down a coal mine, Mr. Edwin (Teddy) Hall, president of the Lancashire and Cheshire Miners’ Federation, put on his old grey suit and made a 70-minute speech to miners who are on strike. It was the longest and most important speech of his life.' These were 1,000 Bold Colliery workers who Hall, of Prescot Road in St.Helens, addressed in a Labour Hall in Sutton. The men had been off work for a week, as a protest against a £5 minimum pay award. Hall clearly possessed powers of persuasion, as all but one of the men voted to return to work.

On July 12th 1944 59-year-old Ernest Marsh from Newton Road in Parr died in the pit cage at Bold as he was being conveyed to the surface. The manager at Bold at this time was Albert Taylor, who lived at Bank House in Burtonwood, and one of his undermanagers was Edward Brown of Wheatsheaf Avenue in Sutton. On December 8th 1944 the pair were assaulted after a dispute with six haulage hands boiled over into violence. There had been a reduction in output in no. 2 pit and one man had been let go. This caused some resentment but Taylor refused to speak to the haulage hands without trade union representation. This angered the men and they pinned the undermanager Brown against the wall and then struck him about the face and body. 21-year-old John Monaghan then assaulted the manager Taylor and threw him to the ground. In court the six were charged with assault and behaving in a violent manner in a mine, for which they received fines.

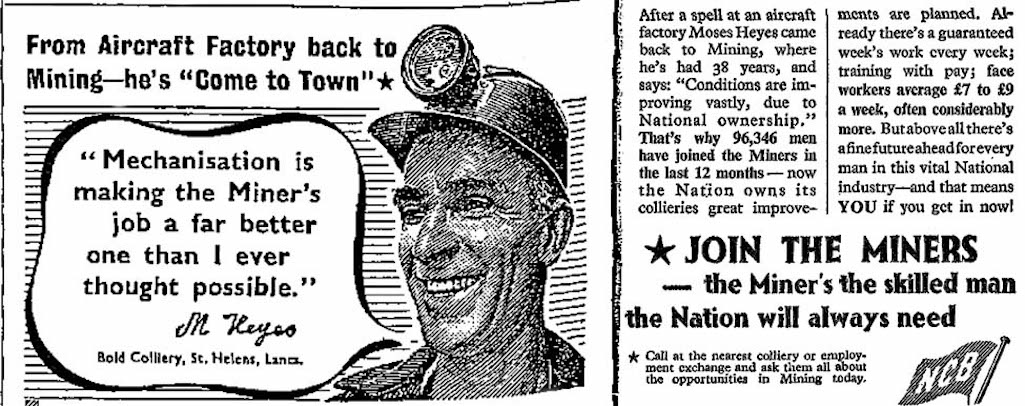

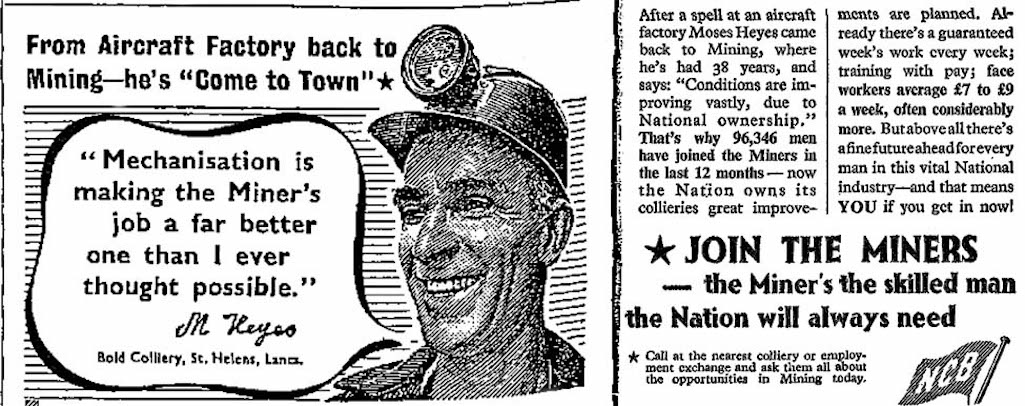

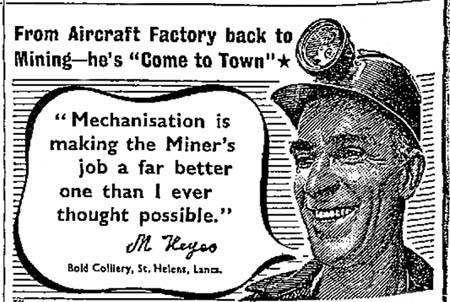

During 1948 Bold's Moses Heyes featured extensively in an NCB newspaper recruitment campaign

During 1948 Bold's Moses Heyes featured in a recruitment campaign

In 1948 Bold's Moses Heyes featured in an NCB recruitment campaign

Production was also disrupted by a strike in early August 1947 through the management's order that miners must work an eight yard coal face instead of the existing seven. A false rumour that a bonus was not going to be paid, also contributed in keeping them off work. After only working one day in the previous nine, the men were persuaded by their miners' agent Charles L. Tyrer to return to work and give the new distance a trial. However these production disruptions were temporary and the real problem was inefficiency coupled with the employment of old-fashioned equipment.

In January 1947 nationalisation of the coal industry began and the newly-created National Coal Board (NCB) decided to completely reorganise Bold Colliery with the intention of making it one of the largest and most modern pits in Lancashire. There were a number of reasons for this. First of all production needed to be stepped up to replace the declining output from other collieries in the area whose reserves would soon be exhausted.

Boreholes drilled to the south of Bold had suggested 60 million tons of workable coal reserves and geological conditions were the most favourable in the area. So the colliery had plenty of potential for the future. Another reason was the decision of the Central Electricity Generating Board to construct a power station on an adjoining site, providing a major customer for the colliery on its own doorstep. The above picture was photographed about 1948/9 and was probably made as a record prior to the colliery’s modernisation. The photo looks east with the Liverpool / Manchester railway line on the extreme left and Bold Lane on the right, with the photographer standing in the field where the last of the cooling towers for Bold Power Station would subsequently be built. To the left at the rear of the picture, you can see the inclined ramp, which allowed coal tubs to climb into the large Screens building. This would have been built after 1939, most probably to increase production during the war, which would justify its high cost.

The large rectangular wooden structure to the right of the screens is the cooling tower for the boilers behind it. Indeed you can just see some of the return steam at the top of the building. The huge slagheap in the middle of the picture displays the signs of variable weather erosion over many years. As would be expected, the much newer slagheap to its right shows far less erosion, with its conical shape being quite rare in Lancashire. Note the tub guide outline, which travels to the top of the heap. A careful examination of the sole chimney indicates that its upper two thirds had recently been rebuilt, with some scaffolding still in place at the top. You can view a larger version of the photo here.

On April 22nd 1949, the NCB announced more details of the £5.4 million investment, which would involve a complete reconstruction of Bold, both on its surface and below ground. The plans would take six years to complete (from November 1949 to April 1955), and over a further five years, the winding capacity would be increased six-fold to 6000 tons a day. The estimate of workable coal reserves was now considered to be as much as 192 million tons, which would provide employment at Bold for decades.

There would also be a new (or reconstructed) coal preparation plant, power house, workshops, sidings, pit head baths, canteen, medical centre and an administrative block. The NCB announced that engineers and contractors Simon-Carves Ltd. would be designing and installing new headgears, using a Koepe winding installation. Two electrically wound 9-ton skips would be designed to operate from two levels, with coal extracted by the longwall advancing method. Twin horizon tunnels would be driven to open up the new reserves of coal and 13kw battery locomotives introduced to haul 30 and 60 cwt. capacity mine cars. A 2000 feet conveyor would take the coal from the Bold washery to the boiler bunkers, which was intended to be ultimately at the rate of 300,000 to 400,000 tons per year.

The new no. 2 headgear at Bold Colliery pictured in 1953 - photo found in the papers of engineer Ronald D'Souza

The new no. 2 headgear at Bold Colliery pictured in 1953

New no. 2 headgear at Bold in 1953