An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 91 (of 95 parts) - Bold Colliery Part 2 (1955 - 1986)

Photo Album 1 | Photo Album 2 | Photo Album 3 | Photo Album 4

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me

Photo Album 1 | Album 2 | Album 3 | Album 4

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

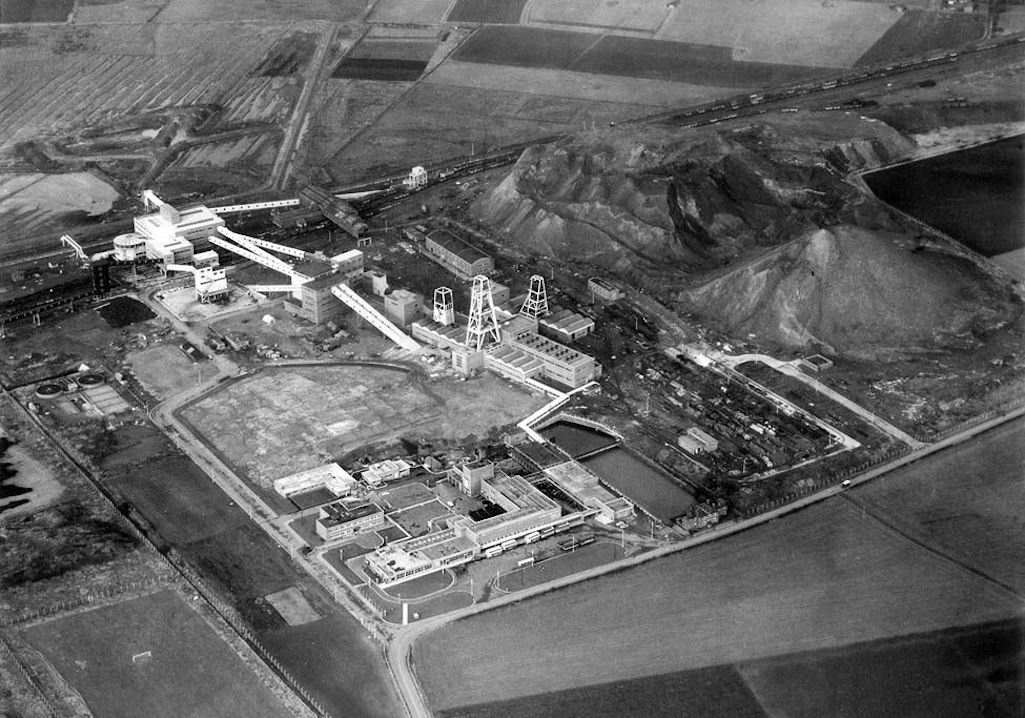

An aerial view of the newly-modernised Bold Colliery c.1955 - From the Cliff Payne Collection

An aerial view of the newly-modernised Bold Colliery c.1955

Aerial view of Bold Colliery c.1955

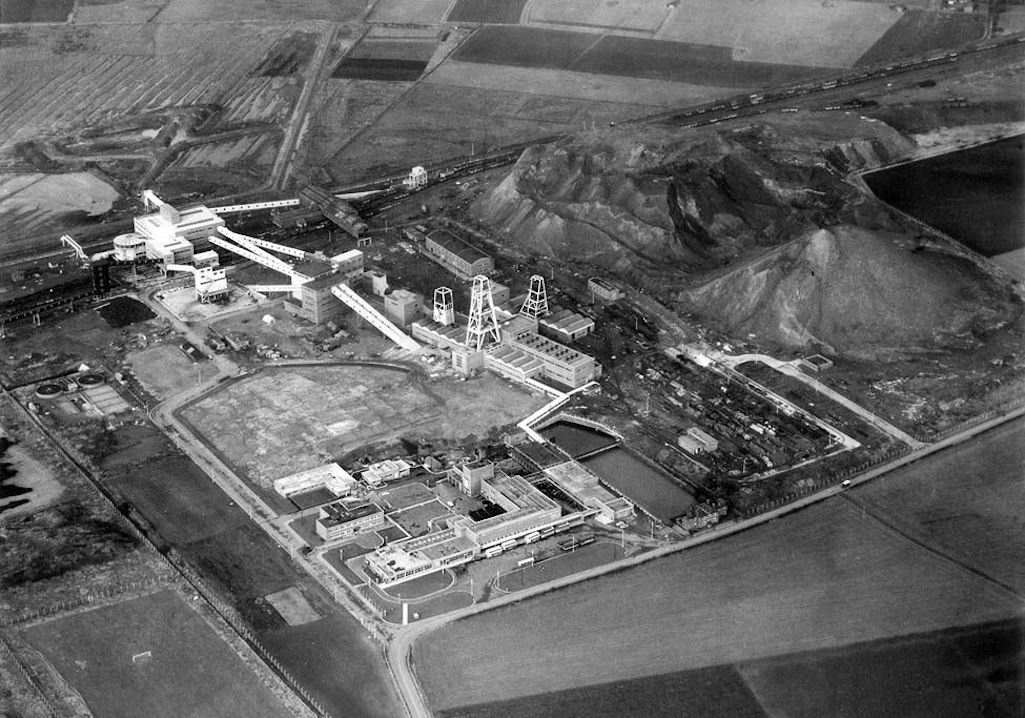

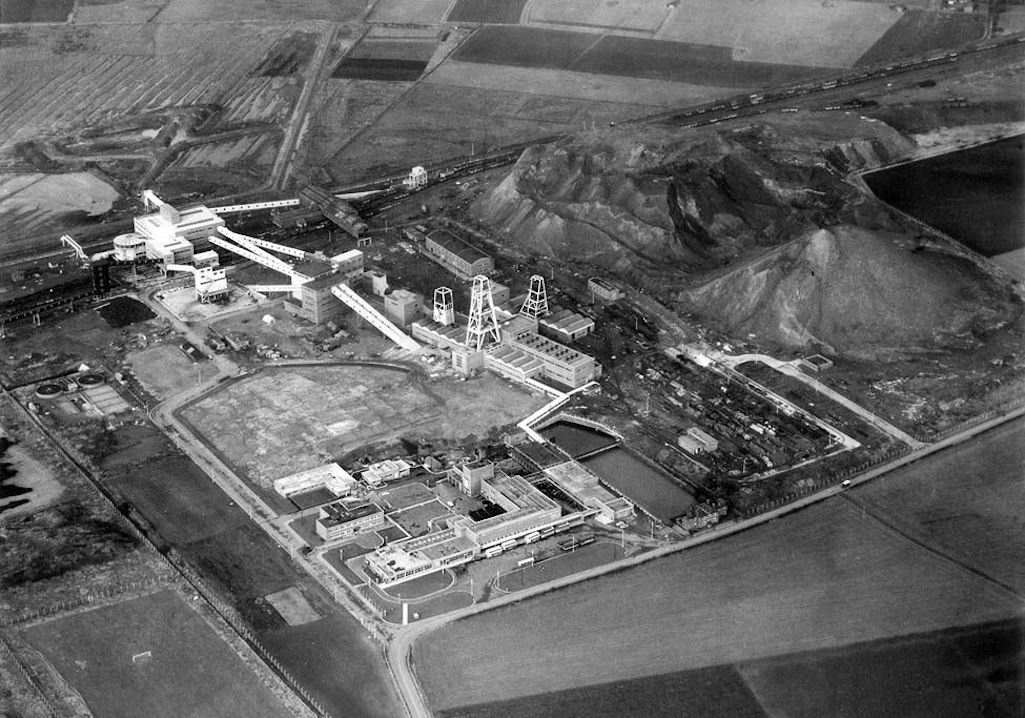

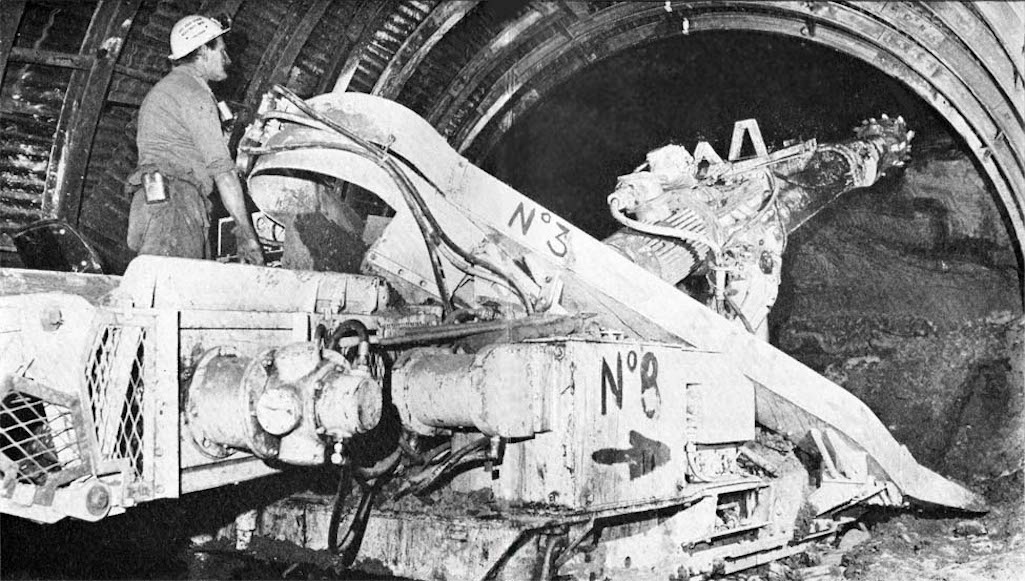

The mainly steam-driven surface machinery was replaced by modern electrical equipment, including winding equipment for the three pit shafts. Modernisation underground was conducted during the weekends and in the off-shift, so Bold was able to maintain its scheduled output while the work was underway. Electric locomotives were introduced to carry materials through high vaulted, well-lit, airy tunnels, with the loading point known by the men as ‘Clapham junction’. However despite the many innovations, tunnel boring was still by dynamite, with blasting only allowing tunnelling of less than two yards a day. No boring machine had yet been invented that satisfied the National Coal Board. There was plenty of coal, with estimates of up to 192 million tons of 'black gold' underground and the Nos. 1 and 3 shafts were deepened to 915 yards to take full advantage (No. 2 shaft had a winding depth of 611 yards).

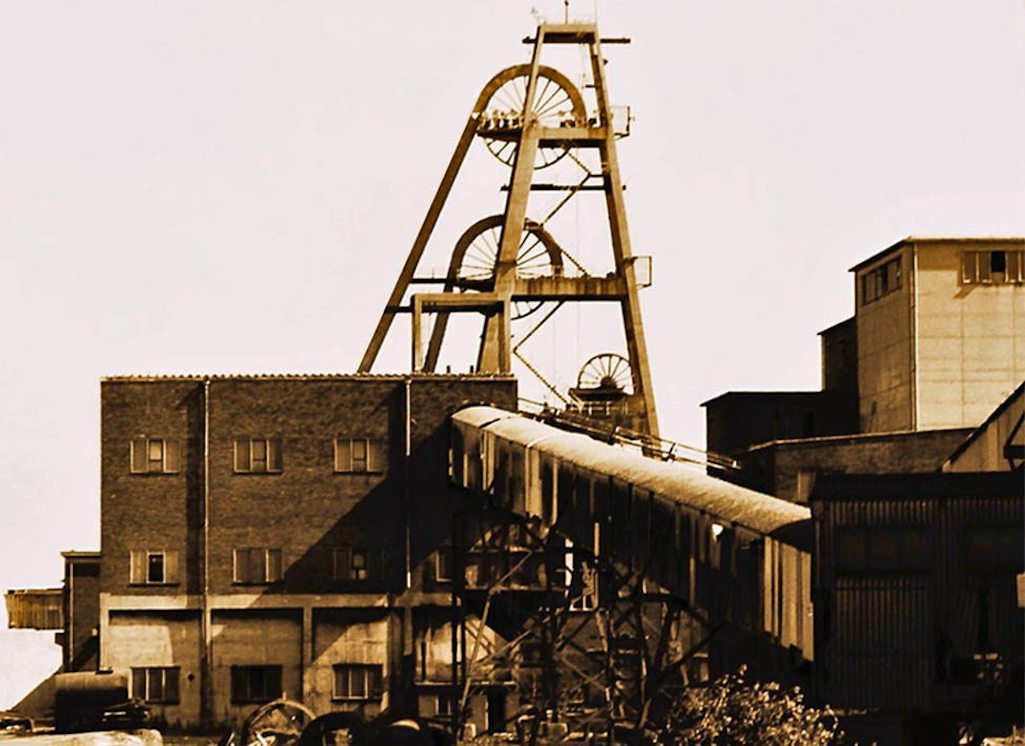

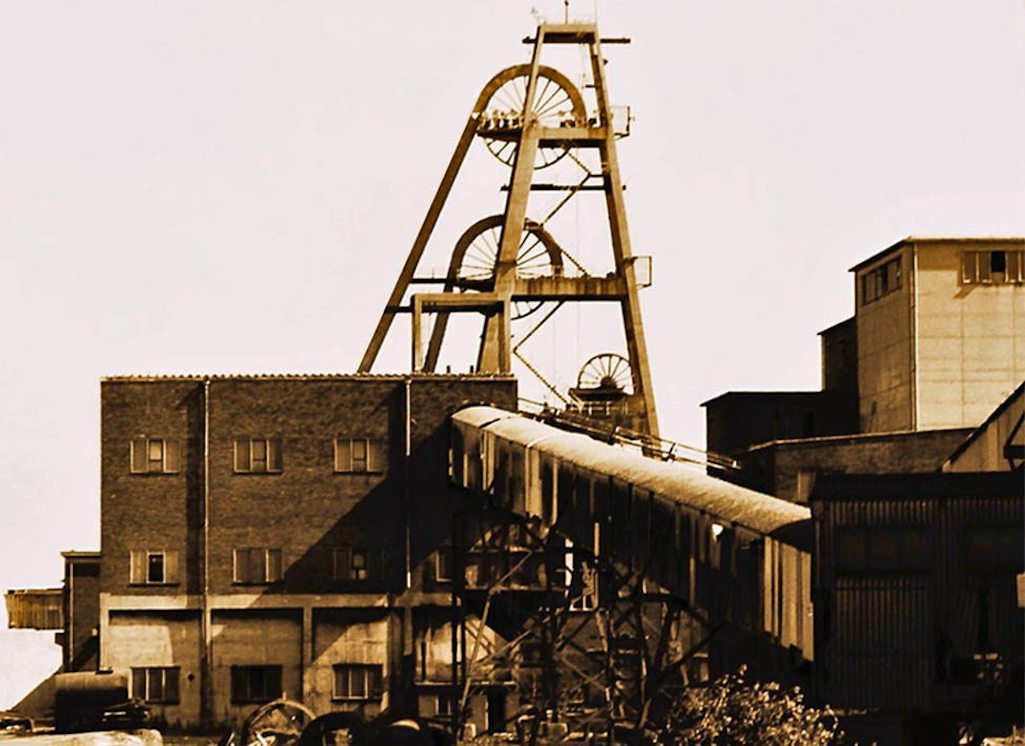

The newly-modernised Bold Colliery pictured about 1955 - From the Cliff Payne Collection

The newly-modernised Bold Colliery pictured about 1955

The newly-modernised colliery c.1955

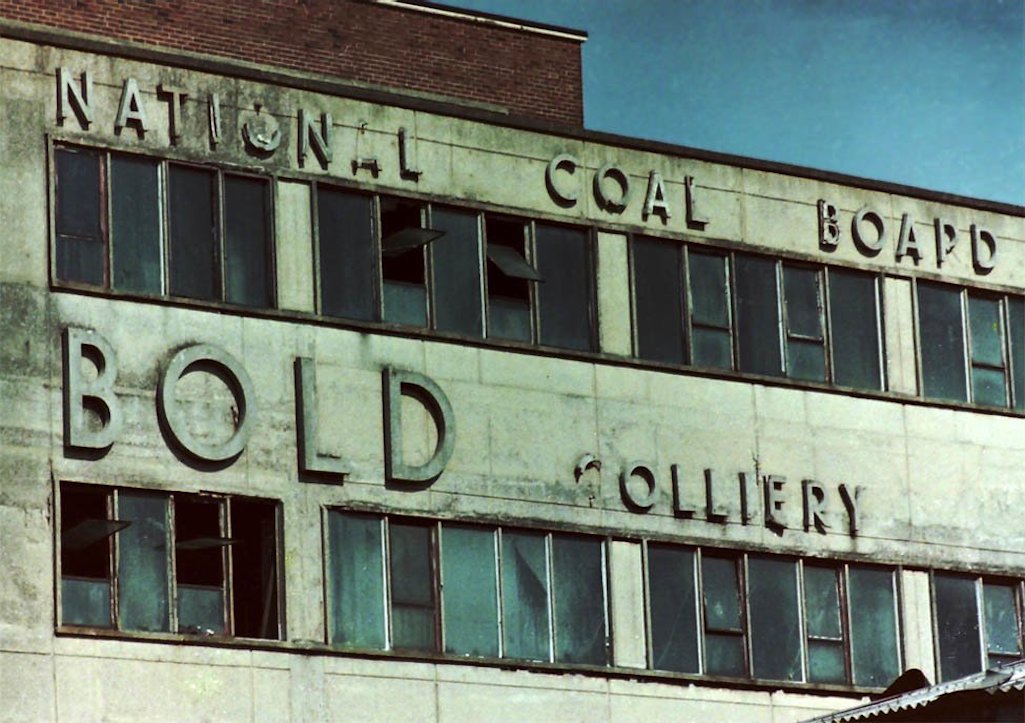

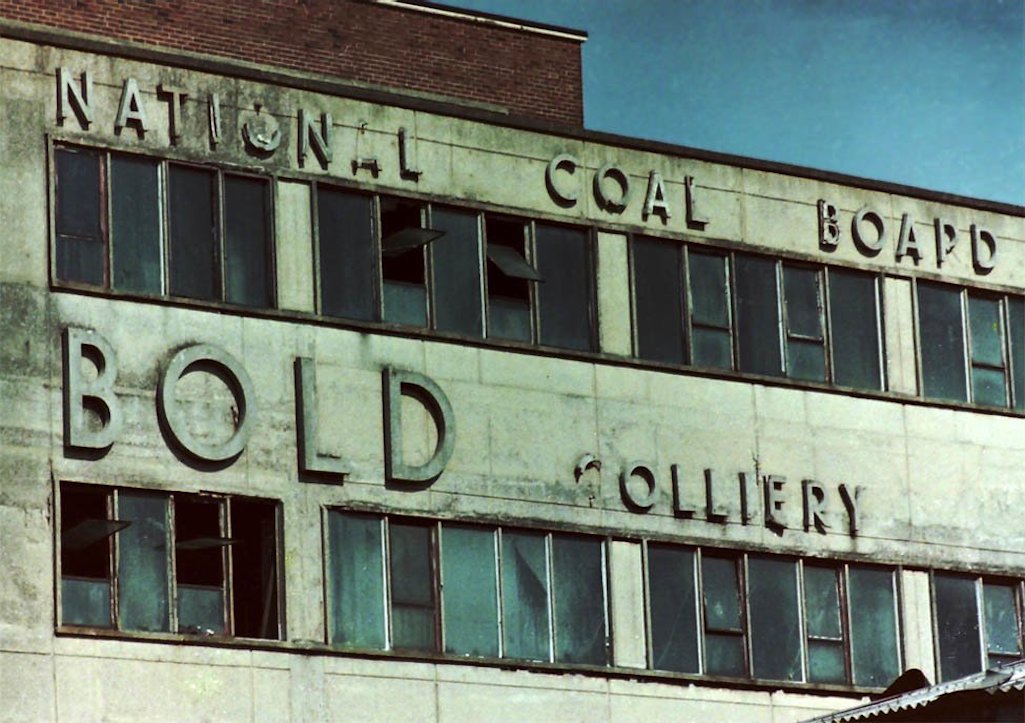

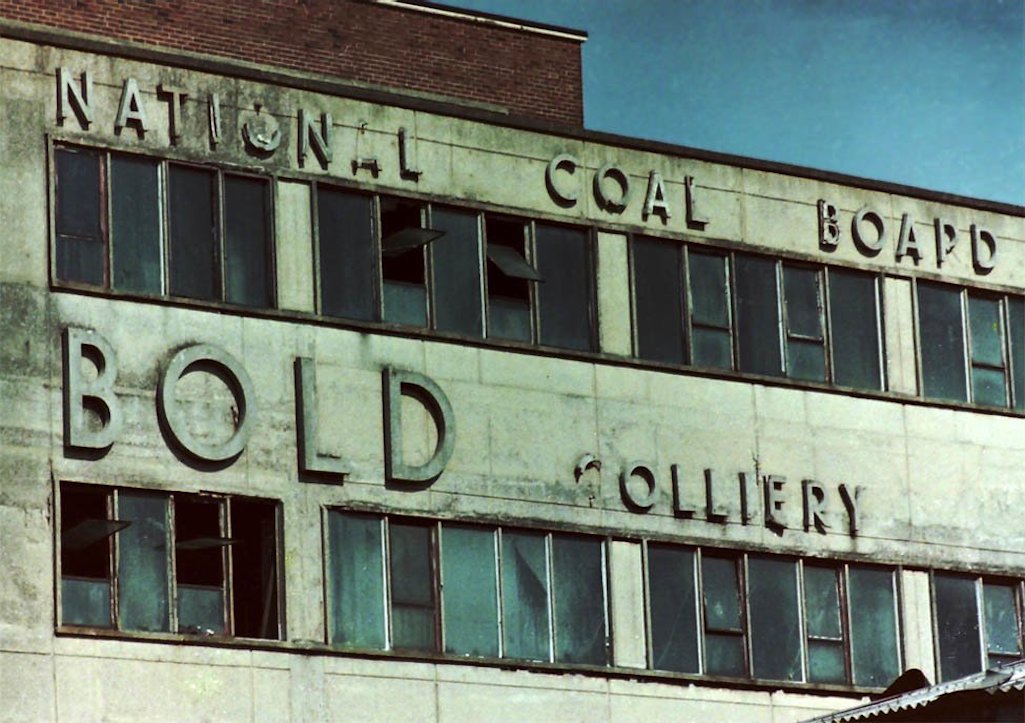

The new 'lighter, brighter' colliery - as described by the Manchester Guardian - was shown off to the press on May 24th 1956. The newspaper described it as 'one of the National Coal Board’s prides and joys', which ‘looks as pleasant as a mine could do’. The St.Helens Reporter said that Bold was ‘probably the most representative organisation in the country’, with twelve nationalities working there, alongside men from St.Helens, Wigan and Bootle. However miners’ agent Sam Unsworth said that the suppression of dust still had to be addressed. He told the journalists who had visited the colliery underground earlier that day, that the dust that had got into their lungs would have done them more harm than the next 200 cigarettes that they smoked.

At that time the workforce totalled 1650, which was 350 under strength. Two hundred miners had been transferred from the Long Lane Colliery in Ashton after it had closed in 1955. The NCB also revealed that two large waste banks, that had dominated the Bold Colliery skyline for 70 years, were in the process of being removed. Two million tons of red shale had already been moved and used as a base for work at Speke Airport, as well as for roads and tennis courts. From 1955 the colliery had instead begun using Bold Moss as a spoil tip and they continued tipping on the ancient moss - which had long provided peat for use as firelighters - until 1967.

The construction by the British Electricity Authority (later CEGB) of Bold Power Station adjacent to the colliery was a huge boon. It was officially opened on September 30th 1955 having generated electricity for the first time in December 1953. The 'blended smalls' coal was transferred directly from the colliery to the power station by means of an overhead belt conveyor. On the occasions when this was not possible, the fuel was diverted into wagons and transported the short distance by rail. Fiddlers Ferry Power Station was also a customer and in total 82% of the colliery's output was used to generate electricity.

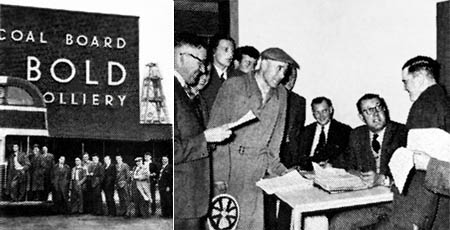

Bold pit deputies; L-R: ?; Arthur Bates; Percy Broughton; Richard Longworth; ? Photo by Neil Selfridge, Id. by Alf Hodkinson

Bold deputies L-R: ?; Arthur Bates; Percy Broughton; Richard Longworth; ?

Bold pit deputies from the 1950s

By now most mineworkers at the colliery were living in Parr, as the National Coal Board had built 612 houses between 1952 and '54, after buying up a farmer's field. Concrete instead of brick was used with a pebbledash finish, so that each house could be built within a week. They also built a large block of flats, shops and several dozen garages for the NCB's vehicles. Bold had suffered from an annual turnover of staff of about 70% and the coal board believed that in providing good, new housing, this would be reduced. Many homes were inhabited by families who had relocated from Liverpool, and a number were Polish. The majority had three bedrooms and for these tenants during the mid-50s paid 25s. 3d. rent per week, which was raised to £39s. 8d. if they left the mining industry.

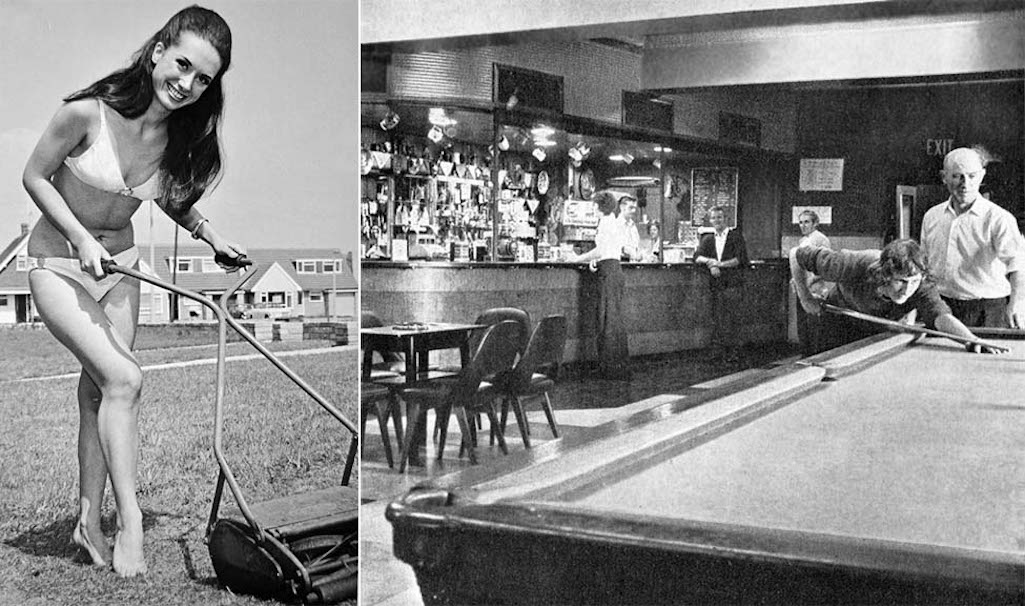

On July 20th 1957 the new Bold Miners’ Institute, in Fleet Lane in Parr, was officially opened by Edwin Hall, the General Secretary of the Lancashire NUM. At the time it boasted the most up to date recreation facility for miners in the country. Costing £87,000 to build and covering some 15 acres, the institute would cater for a variety of sports, with inside facilities for dancing, theatre, refreshments, reading and indoor games. In his opening speech, Hall said the institute was a sign of the higher standards of the modern miners and praised the coal board and the men who had “made possible such a wonderful transformation from what was a derelict pit”.

The manager of Bold Colliery, W. Bibby, said the building was not just a landmark in mining but a measure of the success of the improved relations between management and employees. The Institute’s Recreation Ground only officially opened on June 8th 1963. On that day thousands of miners led by brass bands processed through St.Helens to the ground, where sports, morris dancers, a gala queen competition and a fair were held.

From 1952 to 1961 Ted Lyon worked at the colliery and has endured health problems ever since:

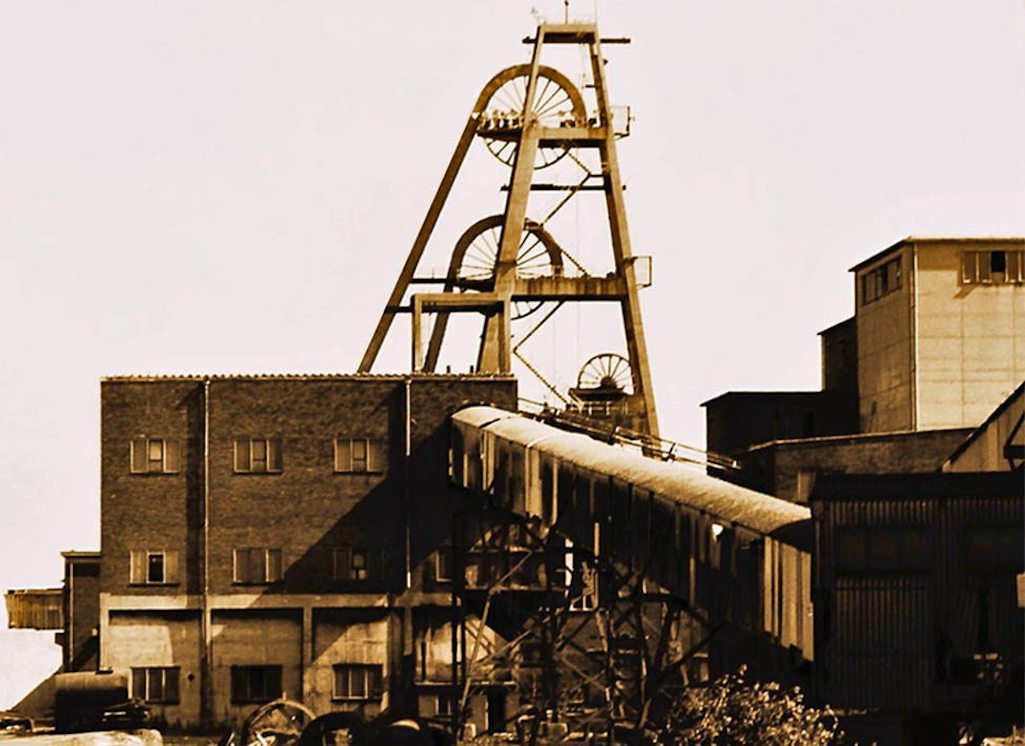

Bold colliery in the 1950s - note Clock Face Colliery in the background and power station cooling tower on the right

Bold colliery in the 1950s - note Clock Face Colliery in the background

Bold colliery during the 1950s

On June 6th 1958, Sir Ian Horobin, Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Power, had a two hour underground tour of Bold. After surfacing he told journalists how impressed he'd been saying "Many people wonder whether we are getting value for money from the coal industry. We are certainly getting it here".

During 1959 proposals to convert Burtonwood airfield into an international airport caused much alarm at Bold. Much of the colliery’s best coal was located 3 miles away underneath the airfield’s main runway, which had been leased to the United States Air Force. The Americans were officially leaving on July 1st 1959 and the NCB had an agreement with the British Air Ministry not to mine under the runway until at least 1962, so as to prevent subsidence. If the authorities agreed to the airport proposals, then Bold’s own plans would have to be revised at a huge cost.

Lancashire County Council and Newton MP Frederick Lee were highly supportive of a new airport, but understandably Speke and Manchester airports were against a rival. Discussions continued on and off for six years, until the NCB announced in February 1965 that they intended to begin working a 4 foot seam of coal directly under the former base. This would entail 600 square yards of coal that was directly under the 1.7 mile-long runway. Mining began in June, scuppering any chance of an airport.

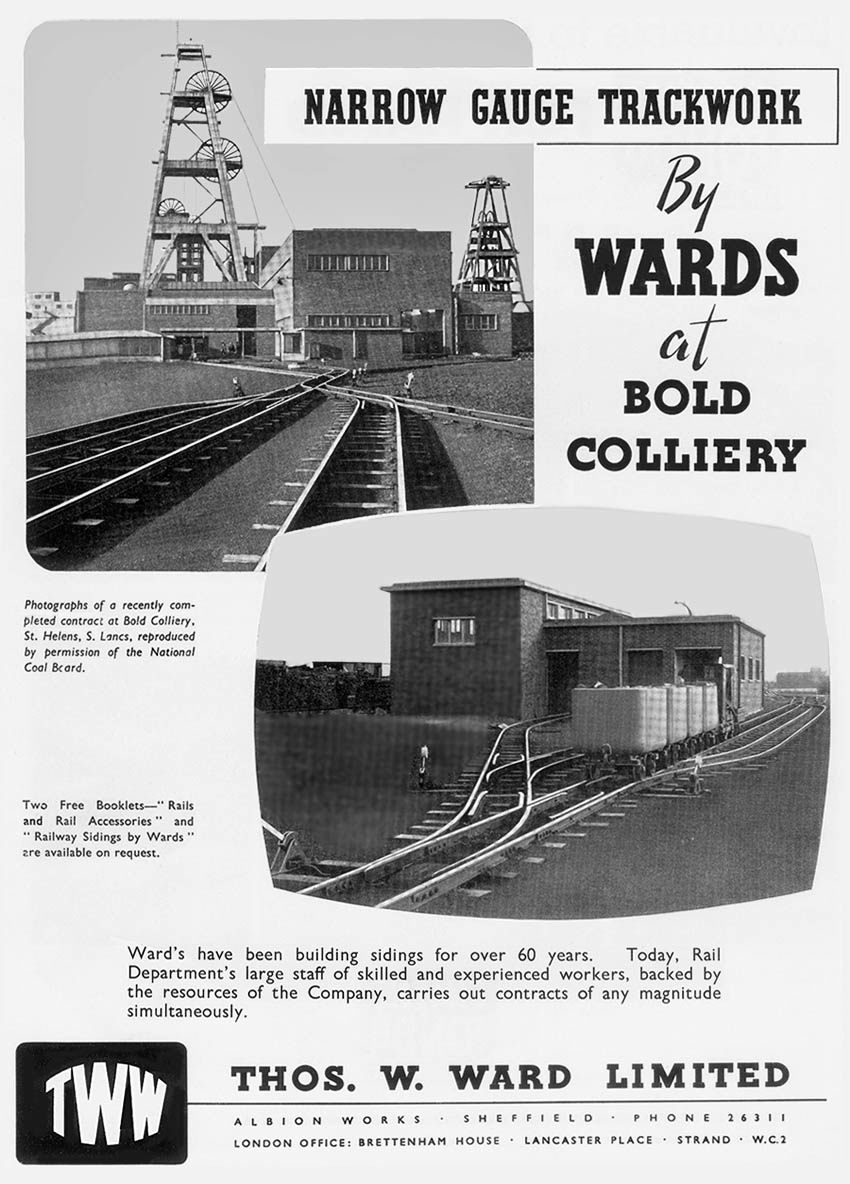

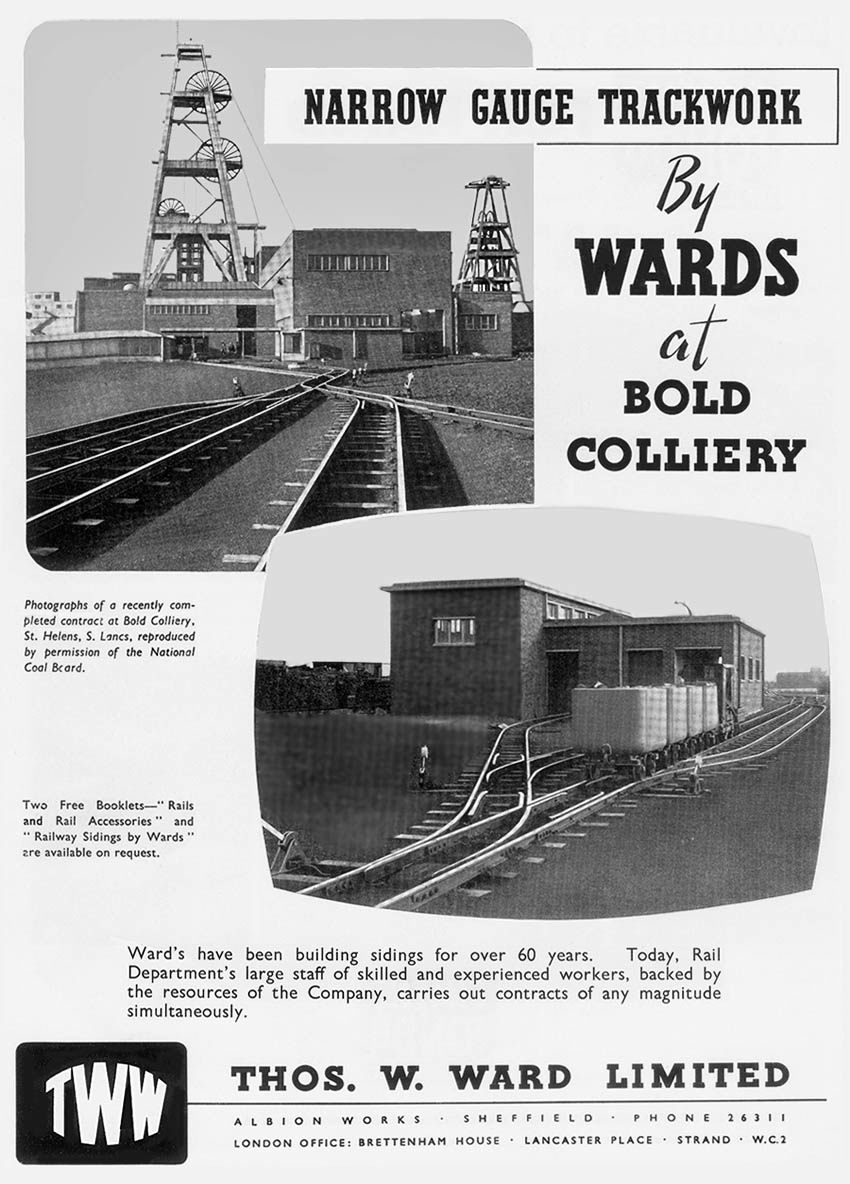

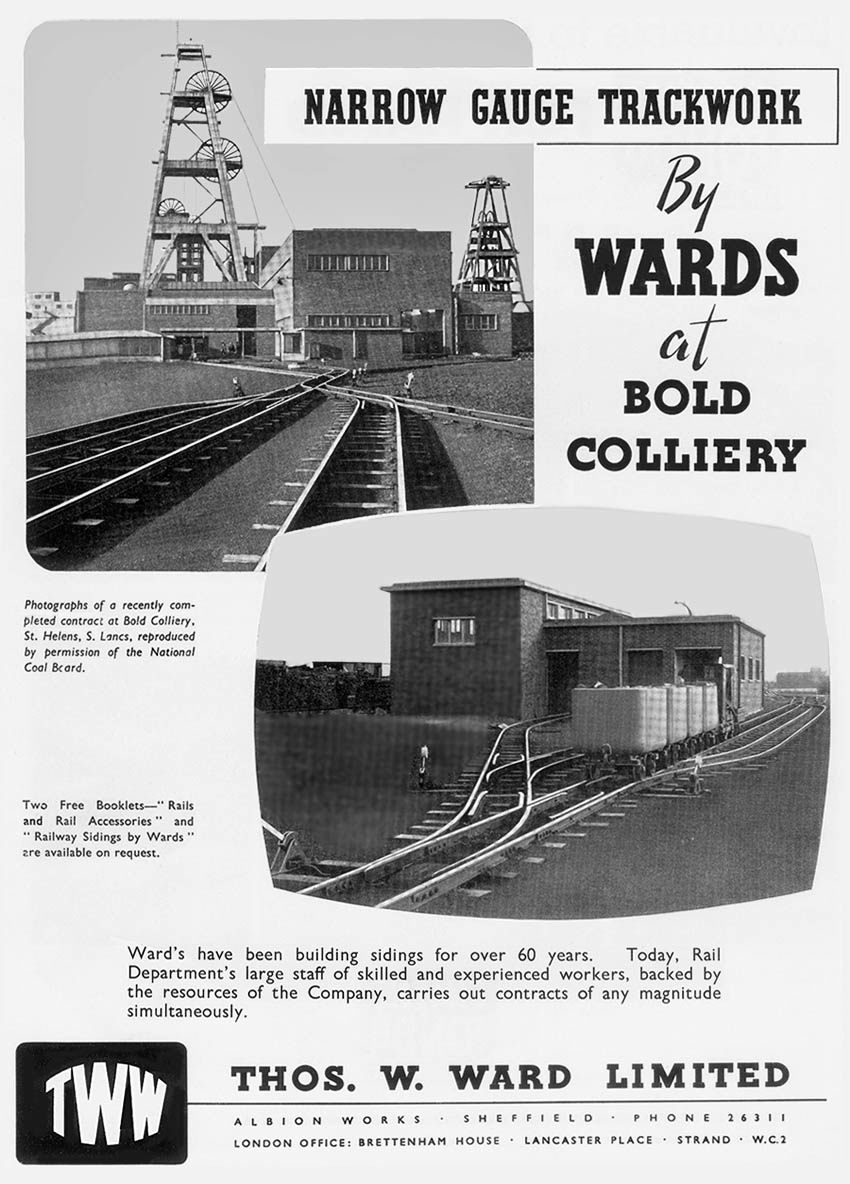

A full page advertisement by Thos. W. Ward which was published in the Railway Gazette of July 25th 1958

Advert by Thos. W. Ward in the Railway Gazette of July 25th 1958

Ad in Railway Gazette July 25th 1958

Seven months later, on June 15th 1961, bailiffs evicted William Donnellan from his coal board home in Berry’s Lane, Sutton. The 36-year-old had worked at Bold for 14 years but had been forced to give up his job in 1960 after developing bronchitis. Since leaving the colliery, Donnellan had kept up his weekly rent payment of 25s. 9d., and other NCB houses in his street were occupied by former Bold miners who had left through illness or injury. However bronchitis was not classed as an industrial disease and the NCB claimed a housing waiting list of 800. So Donnellan, along with his wife and six children, had to go.

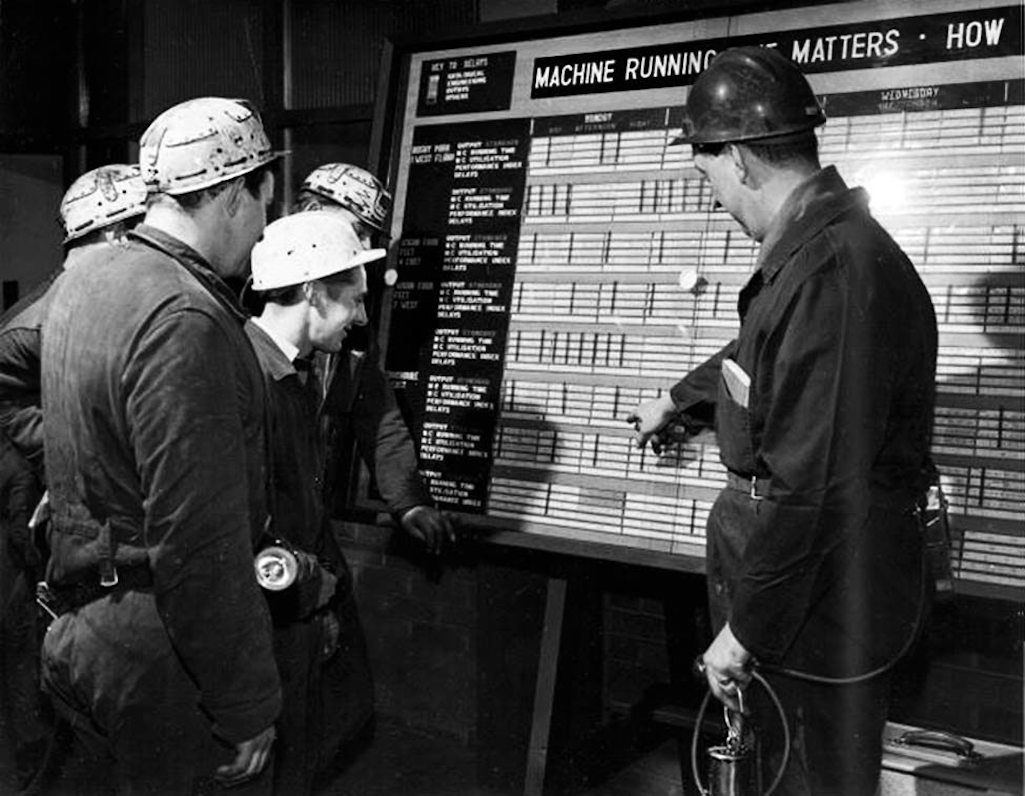

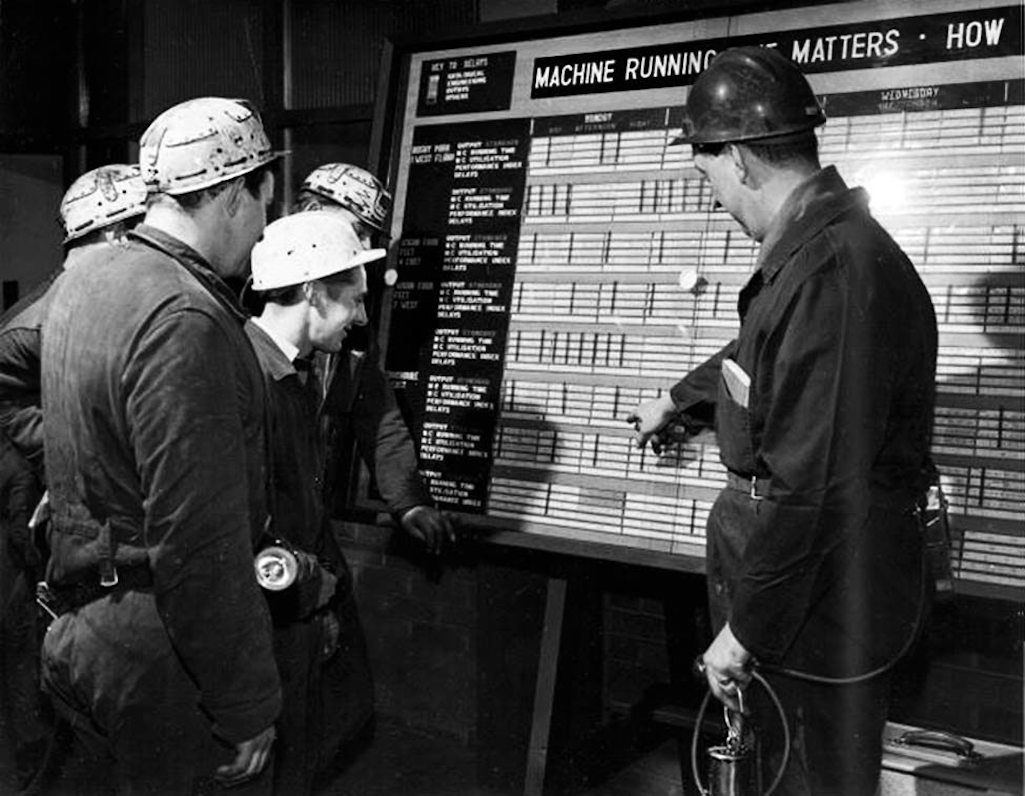

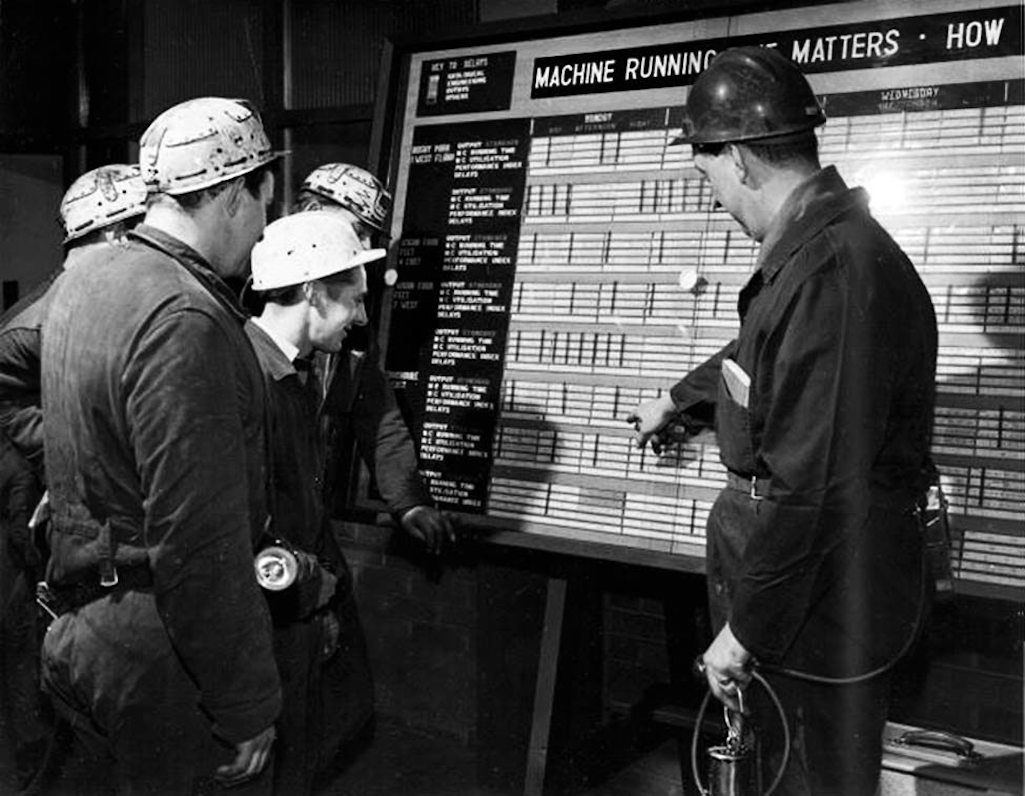

In 1962 a monorail system to transport materials underground was introduced at Bold, to replaced the existing installation. By May 1965 there were 18 in operation, with 14 more on order. Men travelled by the new 'package train', which ran on flexible track to go round corners and up inclines. In 1963 the colliery became the first in the country to have an electronic monitoring installation to keep track of all operations. The communications centre was situated in the administration block and it became the colliery nerve centre, detailing minute by minute information. The installation also enabled remote control operation of pumping and conveyor systems and a safety alarm panel provided audible warnings for smoke and methane concentration as well as water flow.

Underground the telephone system was extended to provide loudspeaker communication directly to the coal face. At a cinema in Cambridge on September 6th 1965, the chairman of the National Coal Board, Lord Robens, presented a live television broadcast from three-quarters of a mile under Bold colliery. Delegates were shown the new electronic system at Bold and The Times reported that the chairman pressed a switch that stopped a coal conveyor belt two hundred miles away and which was witnessed on screen by the delegates.

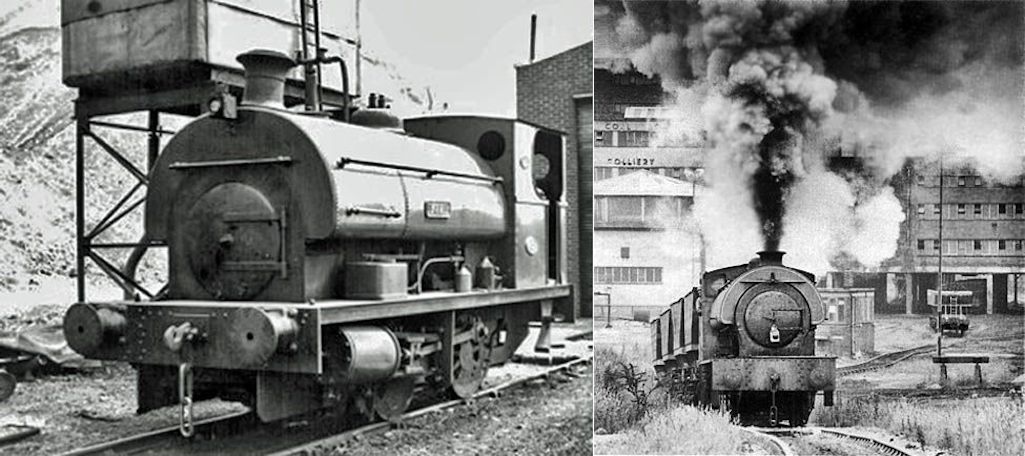

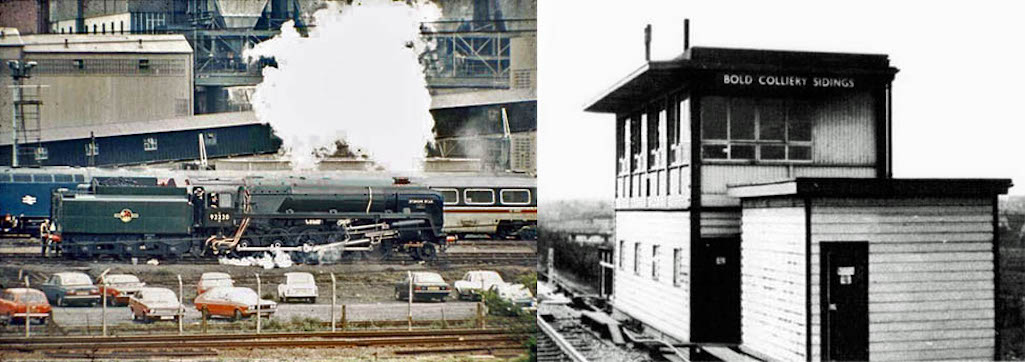

An advantage to the colliery was its close proximity to British Railways main line from Liverpool to Manchester, permitting easy distribution of its coal stocks. Bold was only 13 miles from Liverpool and 19 miles from Manchester. However there were disadvantages in having express trains thundering past the pit and a number of miners lost their lives through walking across the rails (see article Crossing The Line – Rail Deaths in Old Sutton).

On December 29th 1965 there was nearly a major tragedy, when the points for the colliery sidings derailed a passenger train. The six coach Trans-Pennine express was travelling at 50mph with 70 passengers on board when the partial points failure occurred. The points were controlled by the Bold Colliery Sidings signalbox and the leading coach's wheels were pulled in three directions, one of which was towards the colliery's empties reception siding. Driver William Graylish saved the passengers by promptly braking when the train started shuddering and lurching and only minor injuries were received.

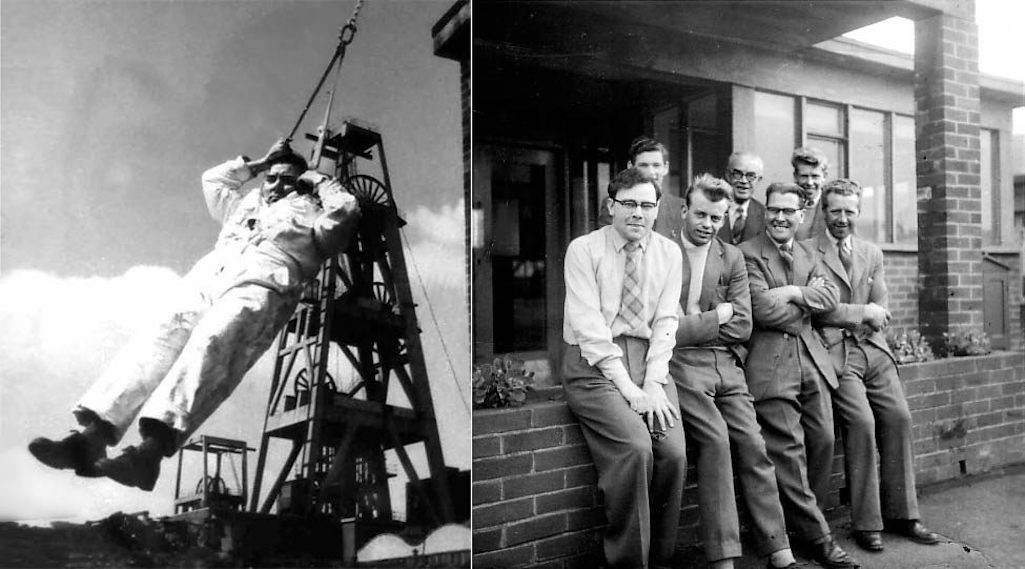

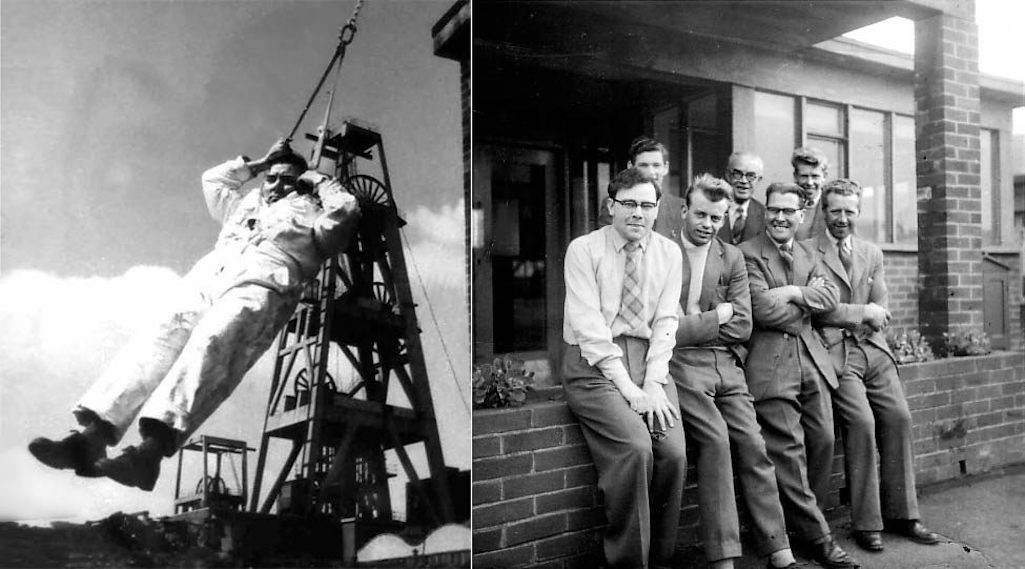

Left: Martin Higgins volunteered to fall off the top of a pumphouse at Bold to demonstrate the effectiveness of a new safety harness; Right: Horace Pugh (front 3rd left) and his team in charge of coal sales at Bold Colliery - contributed by Alan Pugh

Left: Testing a new safety harness; Right: Land (coal) sales team

Testing a new safety harness at Bold

In October of that year the National Coal Board announced that Bold had, over the last 12 months, converted a £750,000 loss into a £50,000 profit. Productivity, defined by OMS (output per man-shift), had increased by 10cwt. to 40 tons 6 cwt. Its coal was in great demand with half going to the nearby power station, 25% to industry and 25% for domestic use. The acting manager Ken Houghton said that Bold’s improved position was down to increased machine running time and reducing the number of coal faces from 7 to 5.

Technological advancements were also improving productivity at the colliery. The coal board’s Mining Research Establishment had developed a smaller drum for the shearer and the idea of fitting fewer but larger picks, in order to extract larger coal for the domestic market. Powered supports were also contributing to the efficiency of operations. The NCB were offering jobs to another 100 men and a union official was talking of a life expectancy for the mine of between 50 to 100 years, with mining operations extended under Cheshire.

In October 1968 a full scale mock-up of a coal face was built in the yard at Bold Colliery. It was part of a nine-month long safety campaign intended to reduce the numbers of shifts lost through accidents. During the year ended March 30th, Bold lost 3,541 shifts through accidents, out of every 100,000 shifts worked. One half of the mocked-up face was in perfect order, while the other half showed mistakes that could cause accidents. The colliery’s safety engineer D. Owen and safety officer J. Forster supervised the men who built the mock face.

On October 12th 1968 the St Helens Reporter stated that new safety appliances called ‘self-rescuers’ were due to arrive at Bold within the next few weeks. The small canister / mask contained a chemical that converted carbon monoxide into small, harmless quantities of carbon dioxide. The deadly gas often polluted the air in coal mines after a fire or explosion.

There was one disadvantage with the self-rescuer in that the process gave off heat. A leaflet that came with the appliance said: “The air passing through the mask will get warm and you will feel this in your mouth and throat. Because of this heat, you may be tempted to take off the self-rescuer. You must never do this, otherwise you may lose your life.”

The St.Helens Reporter on December 14th 1968 featured irate residents of Broad Lane in Collins Green complaining about lorries thundering past their homes. Every 15 minutes for the past 18 months, slurry from Bold Colliery had been taken to a tip at Clock Face Colliery. This was as a result of the National Coal Board being refused permission to extend their tip at Bold Moss.

The residents might have been able to tolerate the noise and the slurry falling off the wagons if it only occurred during the day. However after a five-hour break at 5pm, the lorries resumed their journeys and continued through the night. “The noise is terrible, it keeps me awake.”, said Mrs Hill of 129 Broad Lane. Her next-door neighbour James Orford was also concerned about the safety aspect, with lorries skidding on the slurry-covered surface: “Someone is going to get killed there one of these days. We have had two accidents already.”

On May 9th 1969 the St Helens Reporter stated that plans were going ahead for the opening of a new coal face in Bold’s four feet seam. This would replace the worked out south dip face underneath Burtonwood Air Base that had been badly damaged by crude oil seeping in from surrounding rock formations. Another face – known as the light west face – was reported as already being operational.

In August 1969 it was announced that investigations were being made into the effects of tobacco chewing on the soft tissues of the mouth. The mouths of over 2000 miners were going to be examined by Dr. William Tyldesley, to discover whether sustained chewing was harmful. Dr. Tyldesley had already made a preliminary survey at Bold Colliery, where at least a third of the 1350 underground workers chewed tobacco while working. Many admitted to being ‘chain chewers’, immediately replacing a finished wad with another. Bob Ashcroft, a Bold miner with 17 years experience, told a journalist "I can really relax at the job with a good chew. Tobacco is much better than chewing gum. That seems to collect all the dust and turn into concrete in your mouth."

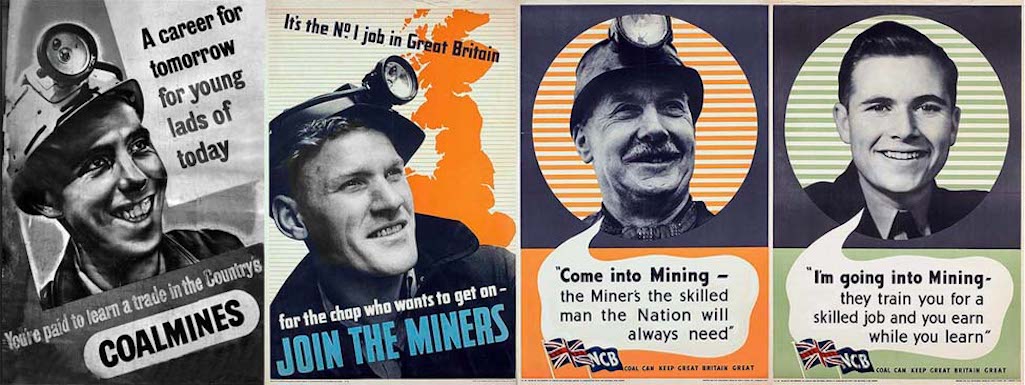

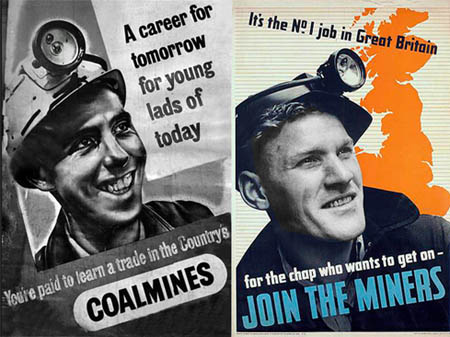

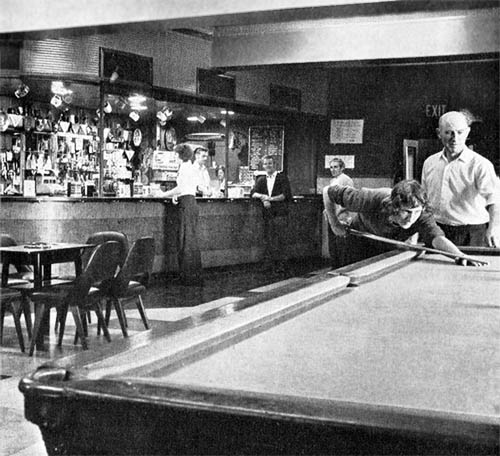

In November 1969 the NCB launched a recruitment drive to fill 500 vacancies at nine Lancashire mines, including 50 at Bold. A four-month long advertising campaign sought to recruit former miners, youths for apprenticeships and men without prior mining experience. The National Coal Board announced in early February 1970 that Bold had smashed both its output and productivity records. Much of the increase was down to the new T-one coal face in the Trencherbone seam which was opening up new coal reserves. The W-eight face in the Wigan Four Feet seem had also accounted for 8,000 tons of the 20,100 total. Recently a new tunnel had been driven to connect both shafts and a 500-yard-long conveyor had been installed in the tunnel, enabling coal to be wound up both shafts. Previously most coal was wound up the No 1 shaft.

On March 6th 1970 the St Helens Reporter had an extensive feature on the mining disease pneumoconiosis with hopes rising that a Government review would lead to increased pensions for the widows of sufferers. The paper said the killer pit disease had widowed forty St Helens' women in 1969 and the case of Jack Williams was profiled. Jack was sixty-seven and for the last twenty years his breathing had gradually been getting louder.

The Reporter wrote: "Now, he cannot breathe like a healthy man, and has to take great desperate gulps of air into his tortured lungs." Mr Williams had been forced to retire in 1962 but during his last twelve months at Bold Colliery he had hardly been to work because of the disease. "I started at Sutton Manor and later went over to Bold", said Jack. "We had two lads but I would not let them go down the pits. The young ones who are going down are making the biggest mistake of their lives."

Left: Miss Bold Colliery, Lancashire Miners Gala Queen entrant Carol Cunningham in 1970; Right: Bold Miners' Institute

Miss Bold Colliery Carol Cunningham 1970 and Bold Miners' Institute

Miss Bold, Carol Cunningham

At the end of May 1970 it was announced that Bold had won the NCB's national safety competition for pits employing over 1,000 men. The colliery had shown the largest reduction in accident rates in the year ending in March. Parkside Colliery in Newton-le-Willows was runner-up. The mineworkers drew lots to share in the £2,273 prize with 28-year-old Arthur Hurst from Ashton-in-Makerfield winning a 12-day holiday for two in Majorca. Each month a safety pamphlet containing poems and limericks that the men had written was issued. There were now over 1,600 employees at Bold, which was considered to be the third largest colliery in the North West.

The Liverpool Echo reported on December 3rd 1970 that Roy Green had come third in an annual students competition organised within the mining industry. The 25-year-old from Union Street was a practising deputy at Bold and attended Wigan Technical College where he studied mining legislation for his under-manager’s ticket. He was awarded the prize for a paper on the installation of powered supports.

In January 1971 Edmond Blakeley from Leigh took over as deputy manager of Bold Colliery, succeeding Ken Houghton who had moved to Somerset. In March of that year it was reported that Adam Walewski had been awarded damages of £500 after being injured in a fall at Bold Colliery. Mr. Walewski was a chargehand ripper at the mine and in November 1968 – while helping to carry a section of arched girder – tripped and fell over another girder lying on the ground.

A fortnight later paneller Joseph Bielak was awarded damages of £10,000 after being injured at Bold in June 1967. The 49-year-old from Liverpool had been operating with a gang of three men working in number two tunnel. A compressed air pipe suddenly burst and the bucket of a shovelling machine struck Mr Bielak on the head. It was stated in court that his injuries and the resulting shock had left him suffering from anxiety, a lack of self-confidence and a personality change.

It was announced at the end of May 1971 that Bold had set a new Northwest productivity record of 42.5 cwt. per man shift, almost 9 cwt. above the average for the region. The colliery was also now officially the safest in the country, having won the NCB’s national safety competition. The miners were awarded £8,000 for the fewest days lost through accidents and the best improved safety record for pits employing over a thousand men.

Inside Bold Miners Institute

The suffering caused by the strike was exemplified on February 11th when two miners appeared before Widnes magistrates separately charged with stealing coal from Bold Colliery. One man had taken just one cwt. of coal worth 60p and was fined £10. The father of four told the Bench that that he had no coal and it was causing hardship to his family. The second man told the court: "I did it because of the children". The strike ended on February 28th 1972, when the miners returned to work.

On January 21st 1972 the St.Helens Reporter published an article entitled ‘A Pitman’s Pittance’, in which they stated that a blacksmith’s striker at Bold took home just £12.70 a week. The newspaper analysed the payslip of Bob Lancaster, who’d worked at the mine for 18 years. The 41-year-old’s gross pay was £19.40 for working a 40-hour week from 7am until 3pm. Automatically stopped from his wage was £1 for concessionary coal money and £1.84 rent for his three bedroomed semi-detached house in Downland Way, on the colliery estate in Parr.

Other deductions for insurance, pension contributions and union dues totalled £1.61, and there was also £2.25 tax. Bob’s wife Martha told the newspaper: “We don’t really live. We survive.” However Bob said he felt fortunate as he worked on the surface and not underground. “Conditions are terrible down there”, he added.

On July 3rd 1972 five surface workers at Bold were rushed to hospital after an explosion in the workshop in which they were working. The men were using welding equipment to repair machinery used in the coal preparation plant when there was a blowback. An oxyacetylene burner caught fire and then exploded, throwing the men over 20 feet. The blast also caused a number of other cylinders that were stored nearby to explode, scattering fragments of metal flying for over 100 yards in every direction. A Fire Brigade spokesman said it was a miracle that anyone had survived.

The five injured men were James Holcroft (60), Wilfred Derby (45), Herbert Stazacker (56), Arthur Ellis (59) and William Bretton (52). In July 1974 Mr Ellis was awarded £4,000 damages and Mr Bretton £20,000. The latter received burns to 50% of his body after being hurled twenty yards into a coal slurry. Over the next four years Bill Bretton had more than ten operations at Whiston Hospital’s major burns unit with a third of his skin having to be replaced.

There was controversy in September 1972 when the National Coal Board began negotiating with St Helens Corporation over the sale of 600 NCB houses in Parr. More than half of them were occupied by miners from Bold Colliery and their families and the NUM lodged a protest with the coal board over the proposals.

Ted Ashton, the head of the lamproom at Bold, retired on January 26th 1973 after 51 years service, having started work at the colliery as a 14-year-old boy. What was remarkable about Ted was that during his employment he never once went underground, with all his jobs having been on the surface. The mine's personnel manager, Ken Harris, presented Ted with a clock on his retirement and invited him to go underground. However he declined saying "After all this time, I don't see any reason for breaking my record".

In May of 1973 it was revealed that Bold’s average coal output per manshift (OMS) during the past year had been 44 cwt. This was the highest output in the NCB’s North-Western Area, which comprised 14 mines, with the nearby Sutton Manor Colliery’s output having been an OMS of 33 cwt. In July 1973 it was announced that the colliery’s General Manager William Monks was leaving to take up a new post in Staffordshire. During his tenure the mine had won awards for safety and greatly boasted its productivity.

With the prospect of a national strike over pay looming, pickets at Bold stopped members of the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shot-firers from conducting safety inspections. The picketing took place over the weekend of February 2nd / 3rd 1974 with the checks instead having to be carried out by management. The strike began on February 5th and led to Prime Minister Edward Heath calling a General Election.

Photo in the Liverpool Echo of February 15th 1974 of Bold Colliery miners on the picket line with Mal Gregory shown third from right

Liverpool Echo photo of miners’ picket line with Mal Gregory 3rd from right

Bold miners on the picket line

An article in the Liverpool Echo of January 28th 1976 stated that steeplejack Joe Selsby had once demolished a 400 ft. chimney at Bold Colliery. A further report on May 21st 1976 stated that former boxer Charlie Fox had died aged 54 after collapsing at work at Bold Colliery. The son of a famous boxing trainer (with the same name) had gone into boxing as a professional in 1934 at the age of 16 and had close on 100 contests before retiring from the ring in 1946.

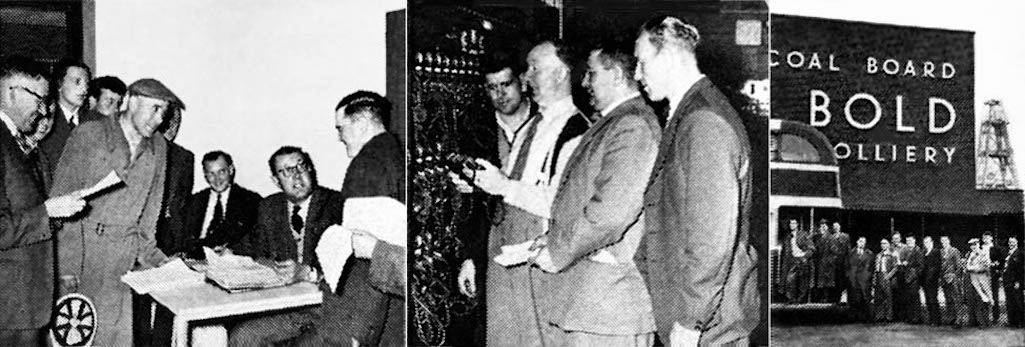

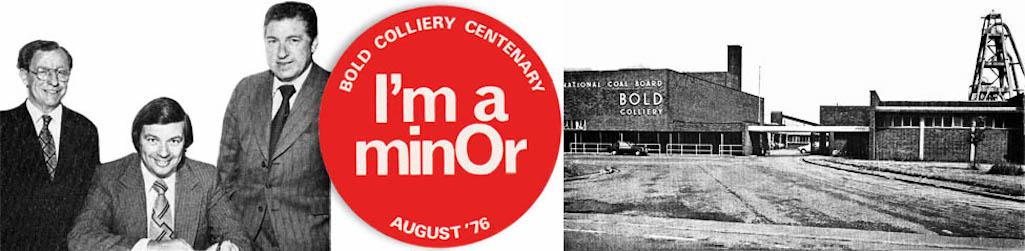

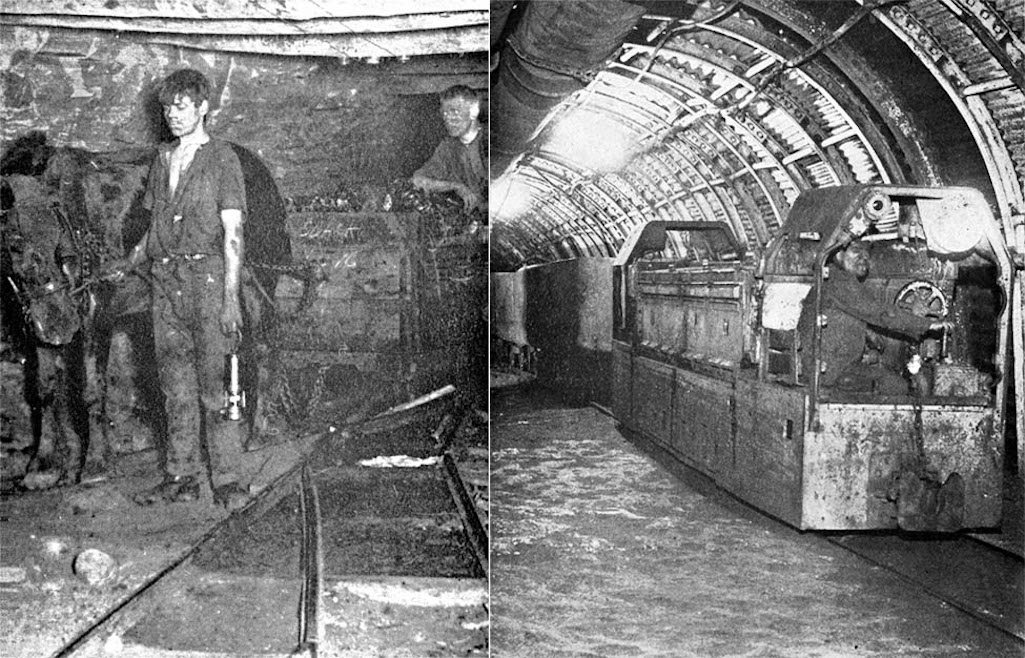

Photos from centenary brochures - L-R Jim Dowd (NUM); Alan Houghton (General manager); Tom Redmond (NACODS)

L-R Jim Dowd (NUM); Alan Houghton (Manager); Tom Redmond (NACODS)

L-R Jim Dowd (NUM); Alan Houghton (Manager); Tom Redmond (NACODS)

Alan Houghton was the General Manager at Bold Colliery at the time and he wrote in the centenary programme about the technical progress at the colliery:

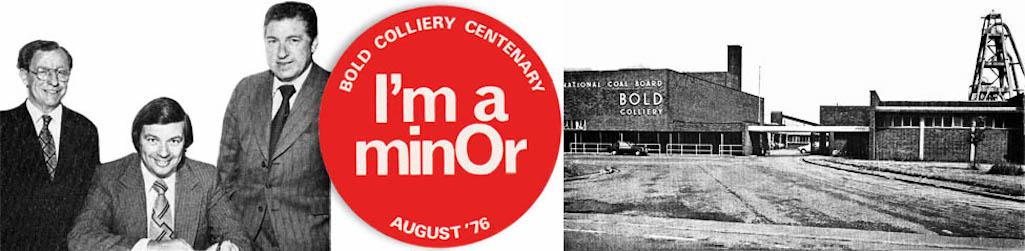

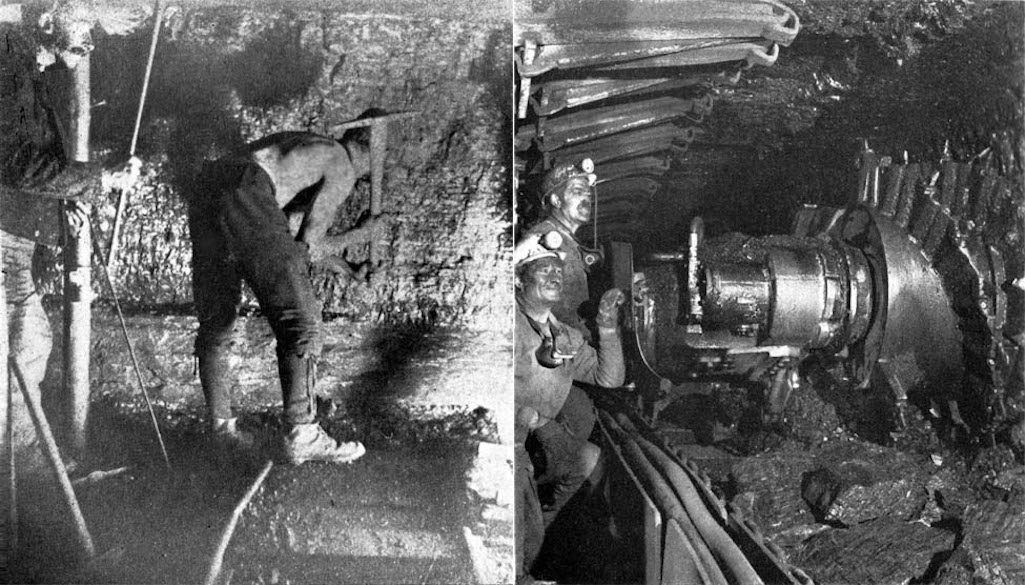

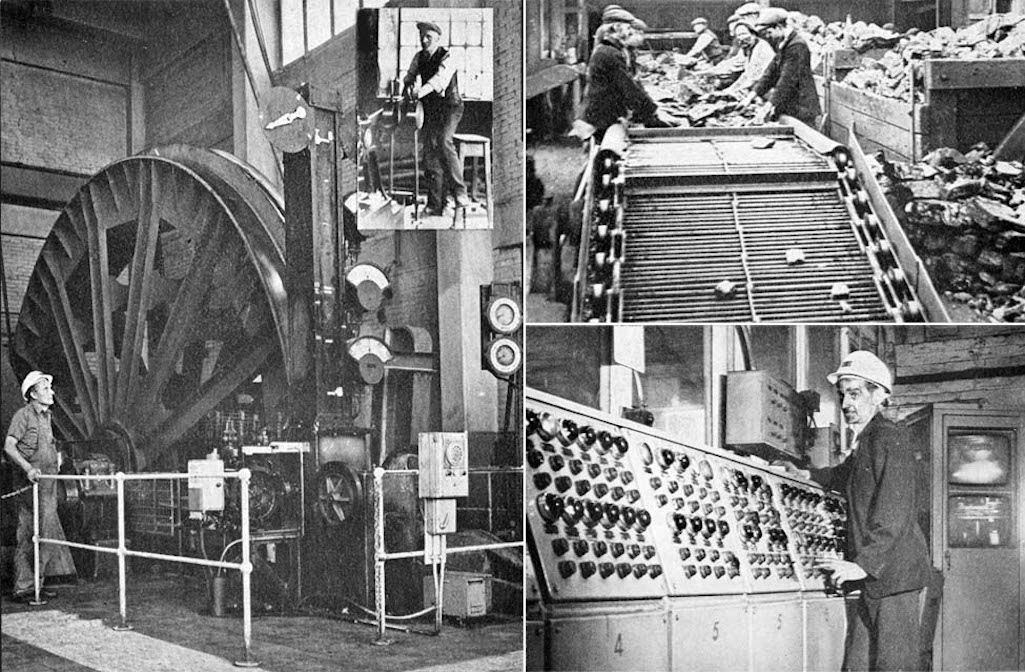

The two pictures on the right contrast the improvements in coal preparation, which for many years had involved the sorting of coal by hand. Women and men undertook this arduous task in screens buildings, grading and separating the coal from dirt. The second photograph (bottom right) demonstrates how manual screening had largely been replaced by sophisticated treatment facilities. The picture shows the process control room - with automated push-button systems and television scanners - which enabled the washing, grading and blending of coal to the particular needs of Bold’s customers.

Some traditional screening did, however, continue but on a very small scale, primarily removing associated mining items, such as timber and steel items, via magnets. The modernisation of Bold’s coal preparation facilities was based on the National Coal Board’s recognition that the market for coal was changing, with a major decline in the use of coal on the railways and a drive for using cleaner domestic fuel. This presented the NCB with the opportunity to increase the value of the end saleable product, through the introduction of new and cost-effective scientific processes.

The band performing at the centenary celebrations was the Bold Miners’ Brass Band, which was formed around 1970 and folded about 1990. They were said to be the last miners' band playing on the Lancashire coalfield. The band were based at the aforementioned Bold Miners' Institute.

During 1976 Bold methane drainage officer Michael Wood won a £100 award from the NCB’s area inventions award panel for inventing an improved stuffing box used in the drilling of methane holes. In January 1977 some long-serving Bold and Sutton Manor miners were sent on a pre-retirement course at the industry’s Old Boston training centre. This was intended as a pilot scheme for the National Coal Board and was thought to be the first of its kind in the country. More than 20 veteran pitmen, who were approaching retirement age volunteered for the 16-hour course, which provided advice on pensions, benefits insurance, tax and even the need for active interests upon retirement. The classes were run by senior training officer, Percy Davies and course tutor Bob Howarth.

Bold Colliery General Manager W. E. Taylor with a party of visitors - contributed by Neil Selfridge, identification by David Owen

Bold Colliery General Manager W. E. Taylor with a party of visitors

Bold Colliery General Manager W. E. Taylor with a party of visitors

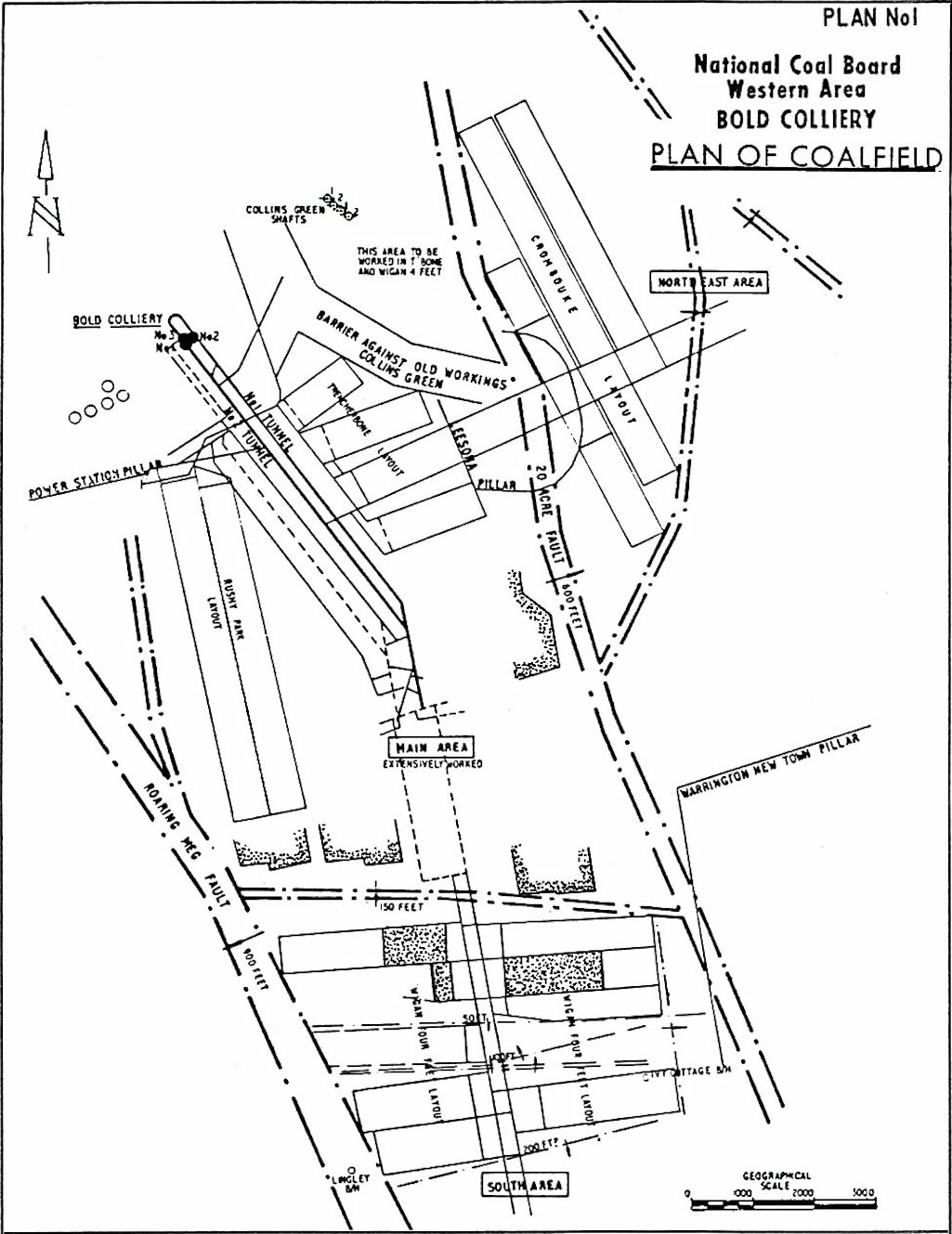

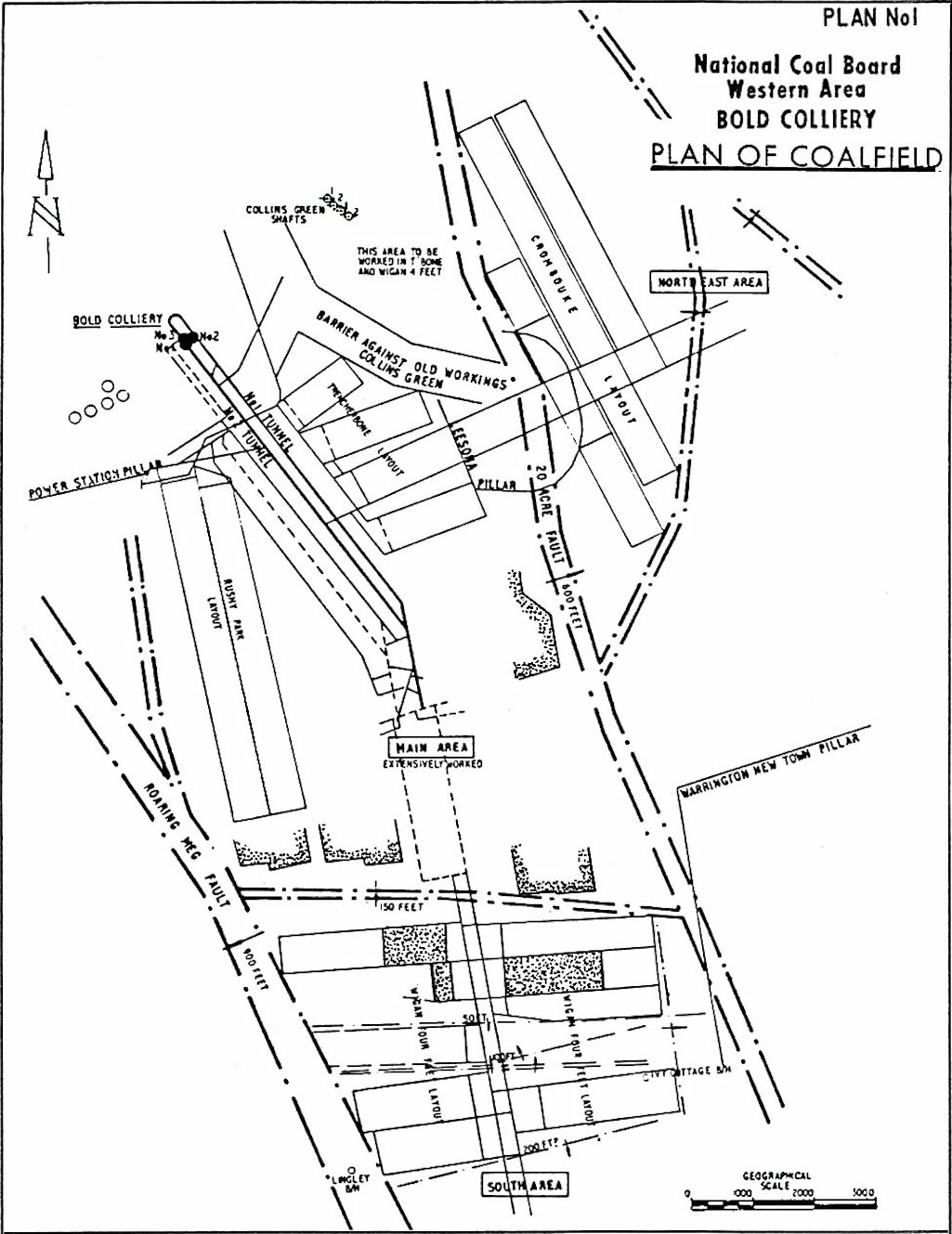

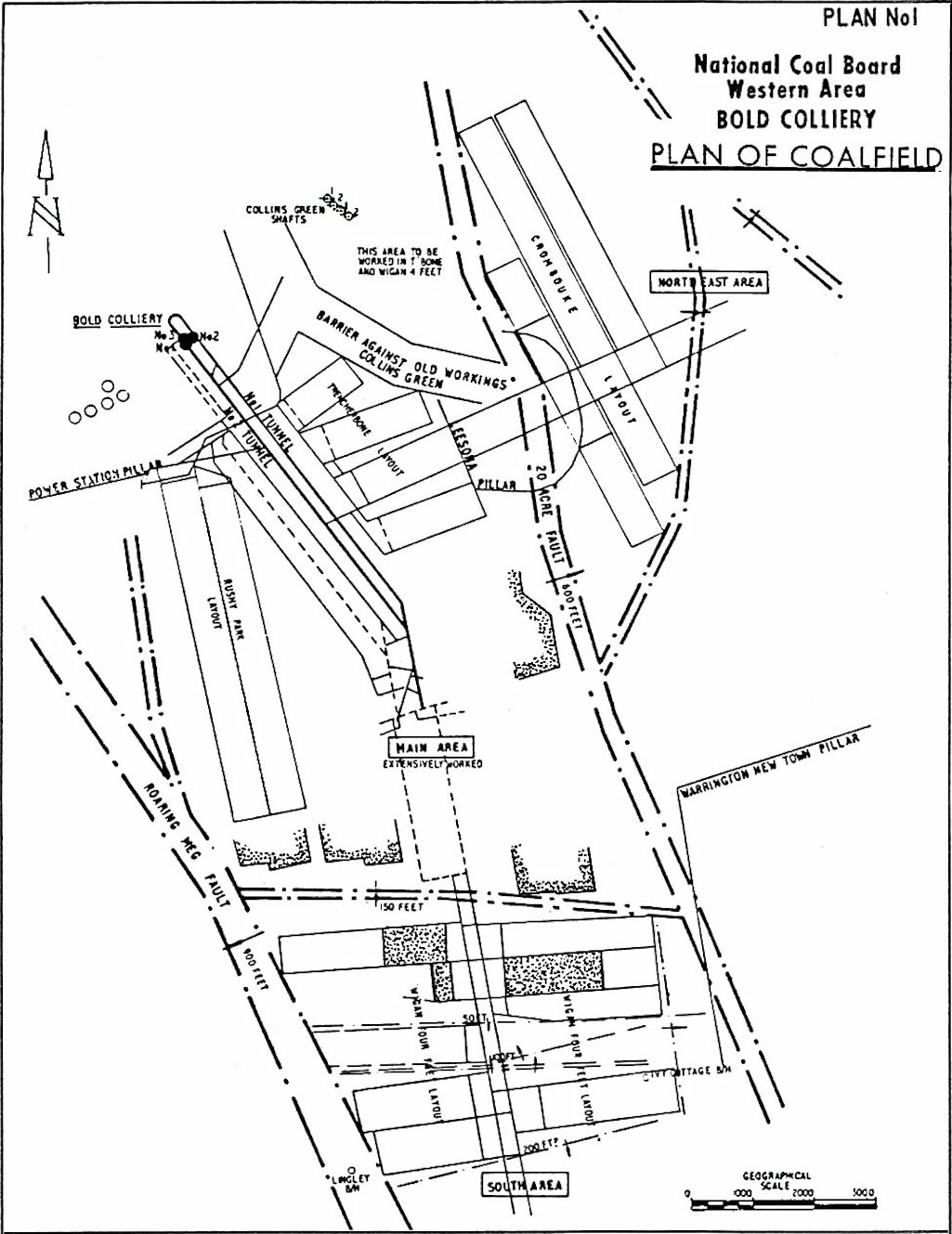

A plan of the Bold Colliery coalfield from c.1977 showing the Main, North East and South Areas

Bold Colliery coalfield plan c.1977 showing the Main, NE & South Areas

Bold Colliery coalfield plan c.1977

In January 1978 the NCB announced a local incentive agreement with Bold mineworkers. Such productivity deals were opposed by union leader Arthur Scargill but could mean up to £40 extra pay for underground workers at the colliery. However the bonuses were at times a bone of contention and led to a walkout by the men on September 29th 1978. A new productivity record was set in mid-February 1979 with an average OMS (output per manshift) of 3.07 tonnes. General manager Alan Houghton said that the success was mostly due to the co-operation from the men and the newly-opened ‘retreat’ face in the Trencherbone seam.

On June 25th 1979 the Evening Post and Chronicle published a revealing article on Bold Colliery, in which manager Alan Houghton explained how he couldn’t mine coal fast enough to meet demand, saying: “I haven’t had a ton of stock here for five years. They’re clamouring to buy it.” It was the rising price of oil during the 1970s that made coal more attractive for electricity generation, with as much as 80% of the colliery’s output now despatched by conveyor belt to Bold Power Station.

However the author of the piece described how the cost of coal was also on the increase and the Central Electricity Generating Board was, as a result, looking more closely at importing cheaper coal from Australia, Poland or South Africa. The article explained how Bold Colliery had huge operating costs:

Working was undertaken purely by the light of helmet lamps and as body temperatures on the face rose into the 80s (F), most men worked stripped to the waist. ‘Methane, the killer gas feared underground, is an ever-present threat’, wrote the author, in explaining how deputy Albert Whitehead from Burtonwood – a veteran of 25 years underground – made regular checks of gas levels on his safety tours.

According to the article only 28% of Bold’s workforce actually produced coal, with the majority of staff being mechanics, electricians, roadway builders etc. Although jobs at the colliery were in great demand, absenteeism was high with up to 30% of workers off at any one time (including rest days and holidays). Despite this staff retention was very high, with 90% of hired mineworkers remaining with the company, producing an average age for Bold employees of 39 years.

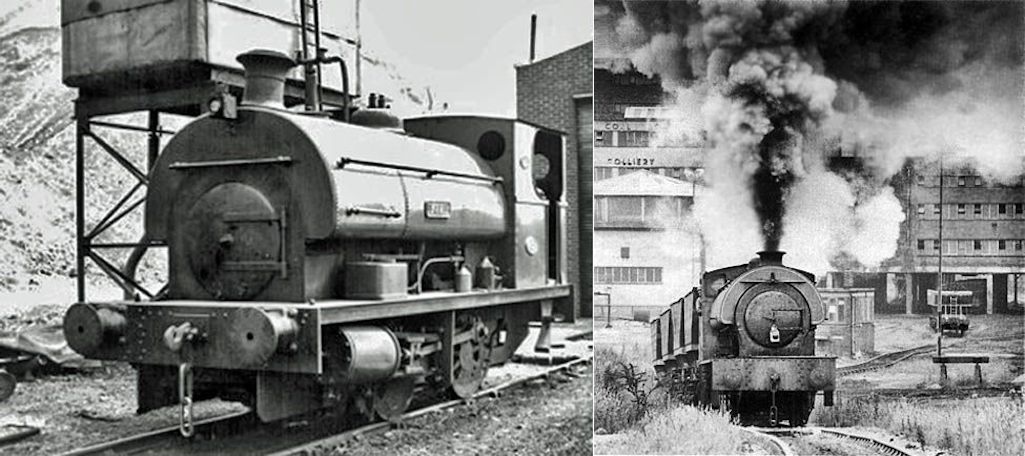

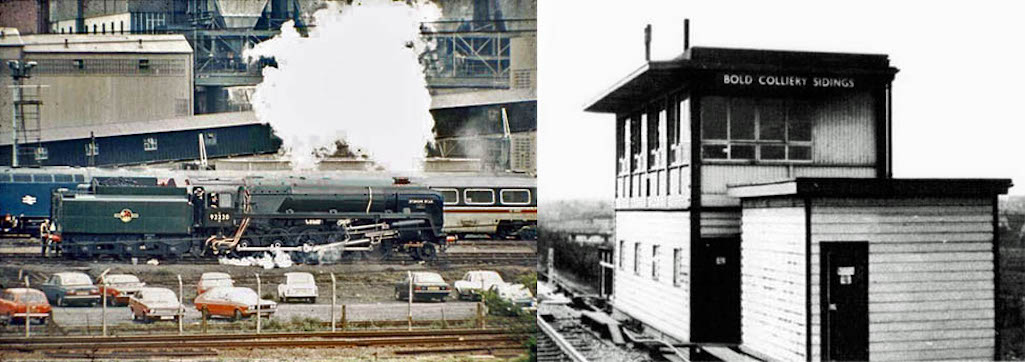

Left: Loco Bold in 1954 - photo by Harry Townley; Right: Robert pulls hopper waggons in 1981 - photo by Brian Dobbs

Left: Loco Bold in 1954; Right: Loco Robert pulls hopper waggons in 1981

Robert pulls hopper waggons in 1981

So Surface Superintendent Harry Simmons put steam loco 'Whiston' to work. Harry had previously been Surface Foreman at Cronton Colliery and earlier in his career, a steam loco driver at Gin Pit at Tyldesley. His expertise of steam engines and their reliability led him to resume the use of steam locos at Bold, which lasted from 1974 until Harry’s retirement eight years later. Dieselisation at the colliery had first taken place in 1957/8. It was then that steam locomotive 'Bold' was transferred to Ravenhead Colliery. The engine was scrapped there in May 1969, having been built in Bristol in 1927 by Peckett & Sons Ltd. and at Bold was works no. 1737.

Whiston was a good engine but soon suffered an accident. A collision damaged its front end, although the engine was only superficially damaged and still workable. Harry managed to get another loco, 'Alison', from the closed Gresford Colliery, as a further backup. The diesel repairs were discontinued and the engine discarded, with Harry referring to it as a monument. He was very keen to have reliable motive power to work the traffic at Bold, knowing that steam locos would work even with ailments. Later 'Robert' built by Hudswell Clark was obtained from Littleton Colliery in Staffordshire and was extensively used. Whiston was repaired and repainted.

The loco shed at Bold Colliery in March 1977 with HE3163/44 pictured outside - photo by Kevin Lane

The loco shed at Bold Colliery in March 1977 with HE3163/44 outside

Loco shed at Bold Colliery in 1977

Steam locomotive Whiston pictured at work at Bold Colliery - contributed by Neil Selfridge

Steam locomotive Whiston pictured at work at Bold Colliery

Loco Whiston at work at Bold Colliery

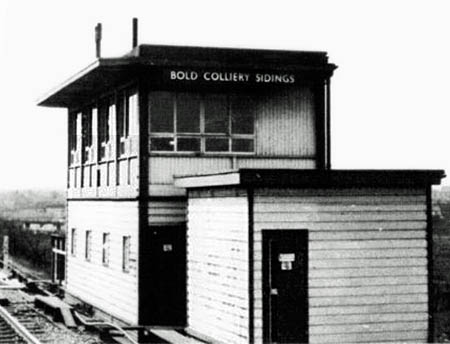

Bold Colliery had a close proximity to the Liverpool to Manchester line. This picture (left) was taken in 1980 at the Rocket 150 celebrations. Note loco 'Evening Star' and Advanced Passenger Train coaches behind it in the Bold sidings. Right: Sidings signal box.

Left: Rocket 150 celebrations in 1980; Right: Sidings signal box

Bold Colliery Sidings signal box

In September 1981 it was reported that geological problems had led to a slump in production at Bold from 8,000 tons a week to 1,000 tons. As a consequence 80 jobs were being axed, although the job losses were covered by early retirement and voluntary redundancy. An NCB spokesman said the drop in output would be temporary, as there were plans to open up three new coal faces over the next eight months:

A new strategy that had been outlined in January 1982 to concentrate on three faces was not paying dividends, due to deteriorating roof conditions and faults. The Rushy Park face was stopped in November 1982 which left just two faces to be exploited. With less need for manpower, the labour force was reduced to 1,080 by March 1984 and No.2 shaft was filled and its headgear eliminated.

However the Coal Board also felt it was not receiving the full support of the men. A memo to employees dated May 23rd 1983 criticised levels of punctuality and attendance and the withdrawal of labour through disputes over bonus payments. General Manager B. Carey added: "It is immoral that a small percentage of the men feel that they only need to come to work when the mood is on them."

Bold’s redundant canaries with Les Barton

Although the introduction of advanced technology had greatly improved mining efficiency, it could still be incredibly demanding work. In his memoir 'The Pit', a former Bold miner using the pseudonym Woden described his irritation at the suggestion that modern mining was all ”push button" and easy. Woden worked under Great Sankey almost four miles from the pit bottom and almost a mile deep in "unbelievably hot" conditions. His job was face installation “dragging in these enormous ‘boiling pieces’, great hunks of hydraulic equipment, using powered windlasses and, with the help of pull lifts and 'tirfers', sheer muscle power.”

Bold Colliery with sixteen ton coal wagons pictured in the foreground - photographed around 1980

Bold Colliery around 1980 with 16 ton coal wagons in the foreground

Bold Colliery pictured around 1980

Upon the so-called 'blacklegs' second day at work, one of their wives was telephoned by a man purporting to be an official who claimed that her husband had been seriously hurt at work. It was described by the coal board as a 'cruel and nasty hoax'. Despite a massive picket line numbering 300, the six strike-breakers continued to cross the line for some time.

Bold Colliery photographed in the summer of 1983 - contributed by Dave Almond

Bold Colliery photographed in the summer of 1983 by Dave Almond

Bold Colliery in the summer of 1983

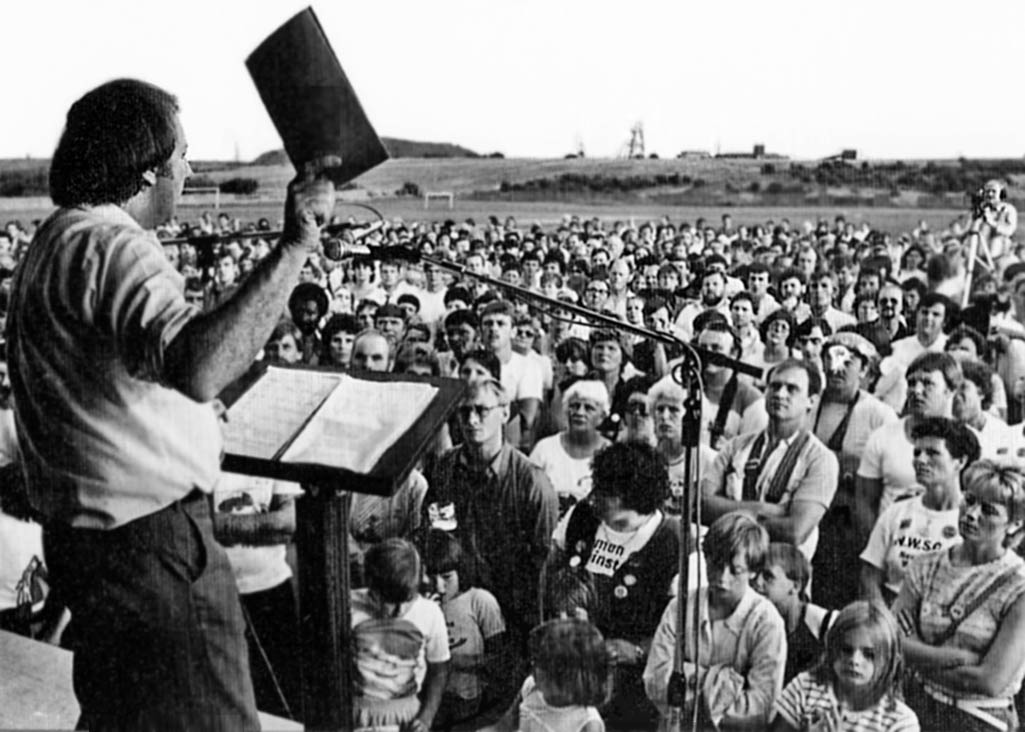

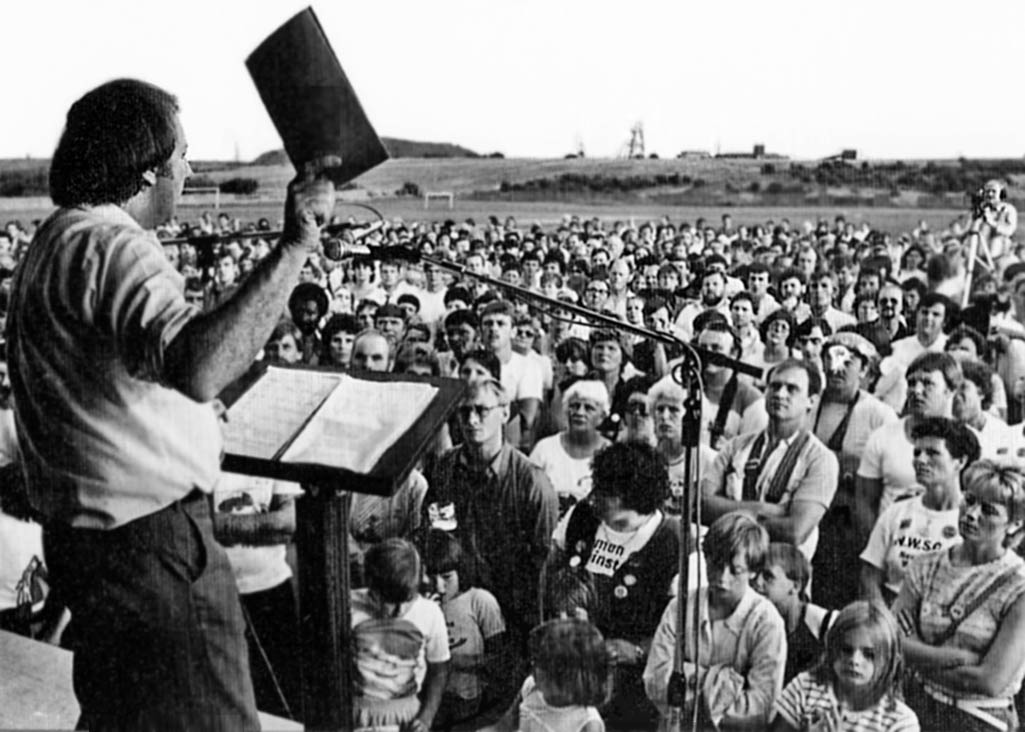

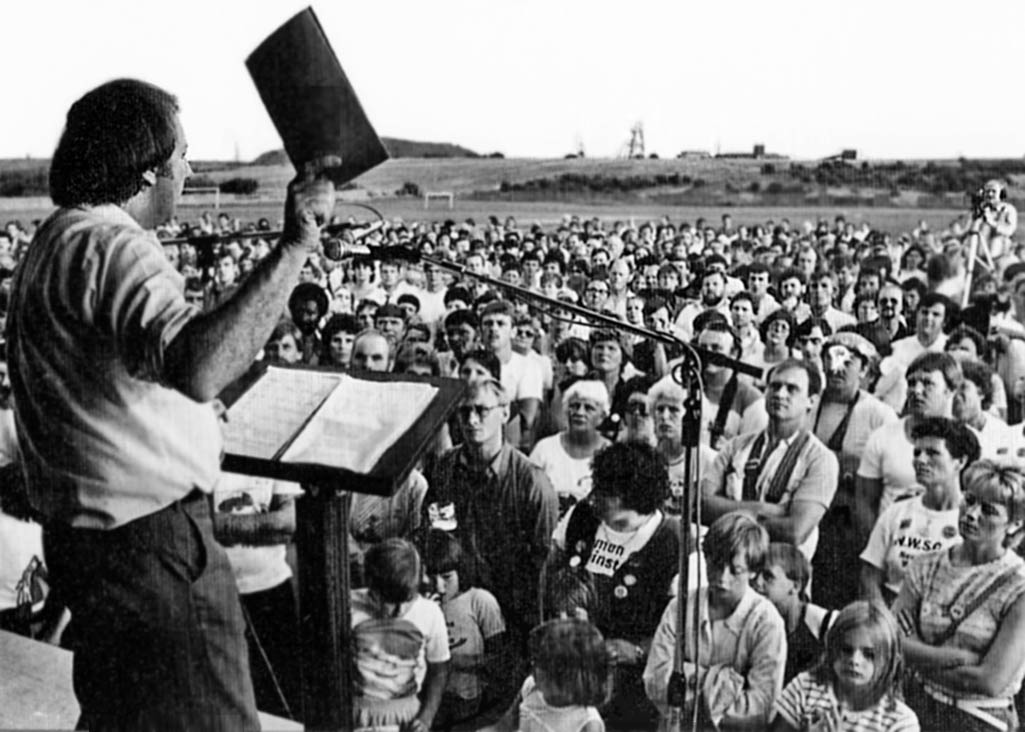

National Union of Mineworkers leader Arthur Scargill addressing Bold Colliery strikers

NUM leader Arthur Scargill addressing Bold Colliery strikers

Arthur Scargill addressing Bold strikers

After ten months despite a drift back to work, 78% of the miners were still striking, although the pit was deteriorating badly. As early as June 5th, the Bold colliery management had declared that most coal faces were "in trouble...We need every man back at the pit".

Bold colliery photographed in the summer of 1983 - contributed by Dave Almond

Bold Colliery photographed in the summer of 1983 by Dave Almond

Bold Colliery in the summer of 1983

It's the end of an era in 1987 at Bold Colliery as a headgear is brought crashing to the ground

A Bold Colliery headgear is brought crashing to the ground in 1987

A headgear is demolished in 1987

Pit head wheel on the site of the former Bold colliery photographed in 2009 - contributed by Neil Selfridge

Pit head wheel on the site of the former Bold colliery photographed in 2009

Pit head wheel on the former Bold site

Capped shaft number 3 at the former site of Bold colliery - contributed by Neil Selfridge

Capped shaft number 3 at the former site of Bold Colliery

The capped pit shaft number 3