An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 88 (of 95 parts) - History of Clock Face Colliery Part 1 (1890 - 1929)

Sutton Manor Colliery | Bold Colliery | Lea Green Colliery

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright & Harry Hickson ©MMXX Contact

Sutton Manor Colliery | Bold Colliery Part 1

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Clock Face Colliery was initially under the ownership of Bold Hall Estate Co. Ltd. who registered their company on July 20th 1893 with a capital of £200,000. Their directors included two millers, a ship owner, a sugar refiner, a colliery proprietor plus industrialist and benefactor Colonel David Gamble. The latter is remembered for donating the Gamble Institute, where Central Library is housed, to the people of St.Helens.

Although established primarily to exploit the minerals on former Bold Hall land, the company's industrial remit also included:

Contributed by Alan Pugh

Pit sinking could be as perilous an occupation as mining and Andrew Neary was fatally injured in July 1896 when water was accidentally tipped onto him. Then the Liverpool Mercury of October 11th 1899, reported how sinker Charles Booth had also lost his life. During the previous year, John Davies of Neill's Row, Bold, sued the Bold Hall Estate Co. for £300 damages after losing virtually all of his sight. This was after gelignite cartridges had exploded in the pit sinker's face.

During the court hearing, it was revealed by John Nolan of Sutton Moss that he and his fellow workers at Clock Face had been forced by the company to contract out of the Employers' Liability Act. The company argued that Davies had caused the accident and had also contracted himself out of the Act, so was not entitled to any compensation. The jury were not impressed by the unsympathetic treatment of Davies and awarded him £200.

On March 23rd 1900, the Manchester Times described how 250 men had been involved in the sinking and construction of shafts over the 'past four or five years' but had now been discharged. They said that the high prices of fuel and iron had also contributed to the suspension of operations at Clock Face as well as the problems with water.

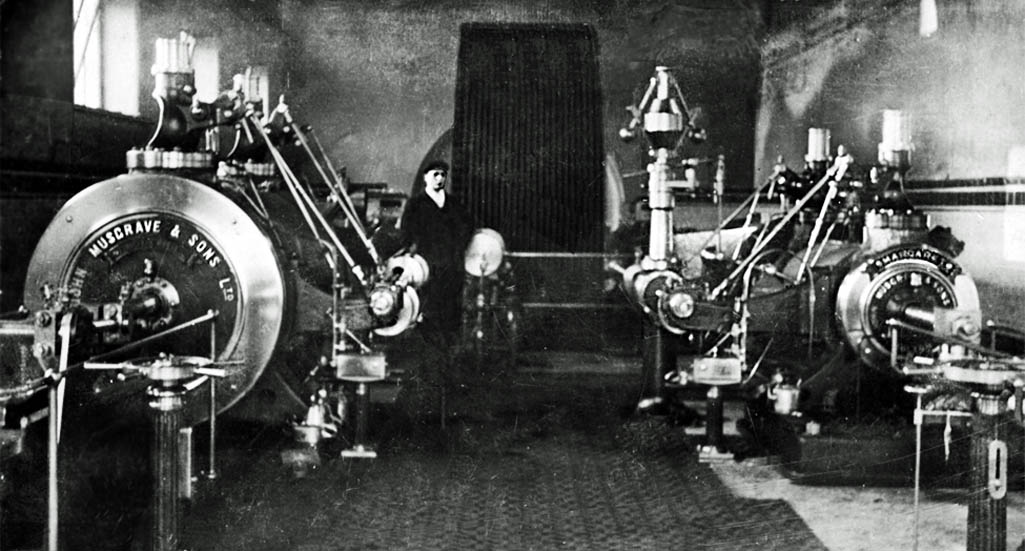

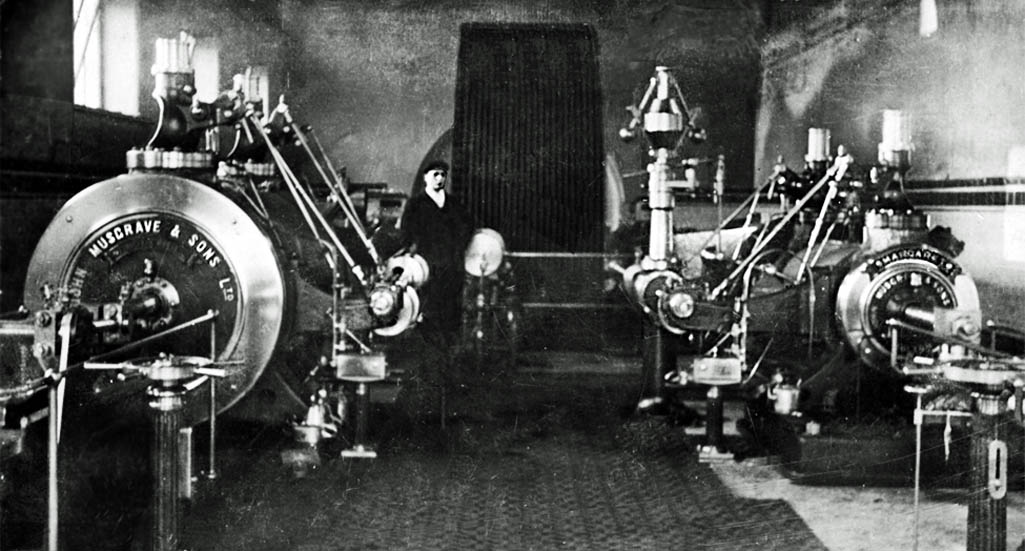

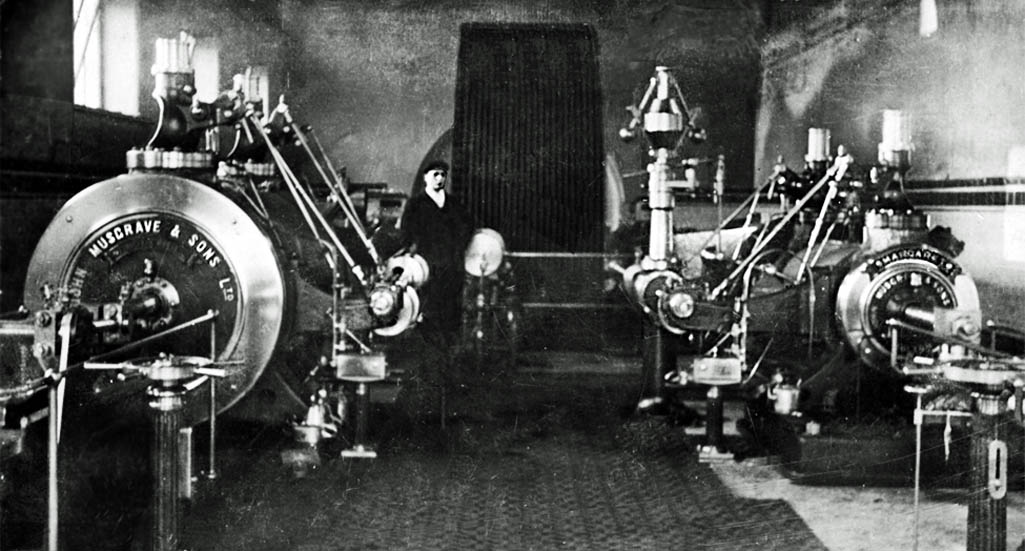

In 1904 the Wigan Coal and Iron Company took over the colliery, which at the time of its formation in 1865 was the largest company in Britain, and applied its many years of considerable mining engineering expertise to solving the problems. The first phase was the application of powerful pumps capable of removing 400 gallons of water per minute from the pits. The pumps were housed in a dedicated building where an attendant maintained and kept them clean and reported variations in operating cycle.

Now Clock Face was able to develop as a business and they converted no. 1 shaft into a pumping pit that coped with over 700,000 gallons of water per day. Of this 500,000 gallons were sold to St.Helens Corporation for use as drinking water. Three ponds on the colliery site stored the water, which had a number of uses, including the washing of newly-mined coal.

An undated photograph of the Musgrave & Sons engine within the pump house at Clock Face Colliery

The Musgrave & Sons engine within the pump house at Clock Face Colliery

Musgrave & Sons engine within the pump house at Clock Face Colliery

Getting Clock Face Colliery fit for purpose cost the life of sinker George Macintosh, who suffered a dreadful death on April 15th 1906. The 27-year-old from Clock Face Road lost his life while fixing steel wire rope down a shaft. This was intended to support pipes that were needed to pump out water. Macintosh was 200 yards from the surface in a small sinking tub with three other men when rope suddenly came loose.

It fell some distance down the shaft and cut off Macintosh's head and left arm. These fell 300 yards to the bottom of the pit, leaving his torso in the tub with the three shocked men. Fellow sinker Michael Mahon was badly injured, although carpenter Alfred Roby of Leach Lane and sinker George Thompson were uninjured. At Macintosh's inquest it was revealed that he'd decided to save a little time in uncoiling the rope down from the top of the pit, instead of from the pit bottom up.

This, he argued, was needed to serve the expanding population of the district, which until very recently had been mainly agricultural. The 200 miners and surface workers that were presently employed at Clock Face Colliery required accommodation and so a large number of houses were being built. At the licence hearing it was stated that the colliery had plans to expand its workforce to between 1000 to 1500 employees, so a considerable expansion of the village was anticipated.

Clock Face undermanager John O’Brien

For several years he was secretary of the Lancashire and Cheshire Mines Rescue Workers Association and in recognition of his local work in the Association, he was awarded the medallion and certificate of Clock Face Rescue Committee. Away from the mine O’Brien represented West Sutton Ward on St Helens Town Council from 1920 until 1947. In 1934 he became the first Clock Face man (albeit living in Forest Road, Sutton Manor) as well as the first Catholic to be appointed Mayor of St.Helens.

Sulphur fumes and smoke would have been injected into the totally-dark room, with obstacles placed in the way of the rescue team. Dummies were used to represent injured miners, temperatures were elevated and there was even inclined floors to simulate a fault dip or incline tunnel. In all these conditions they had to communicate as a team, erect roof supports, clear roof falls, install temporary ventilation measures such as brattice cloth, treat the injured and get personnel out safely on stretchers.

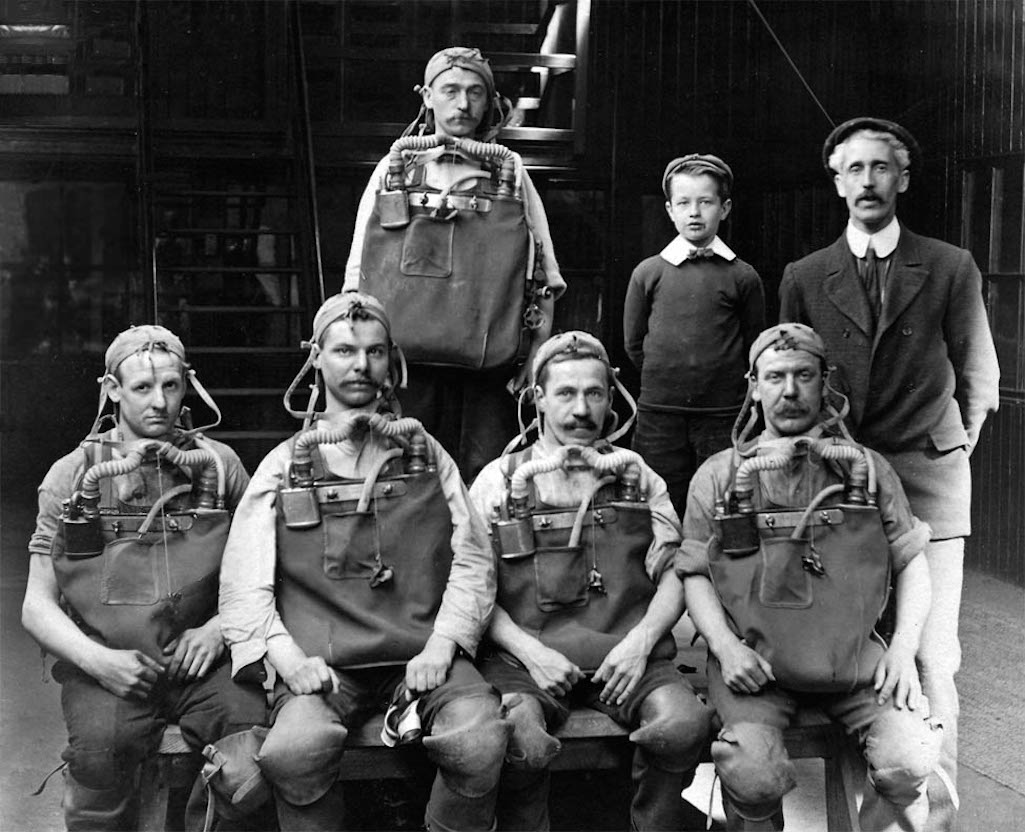

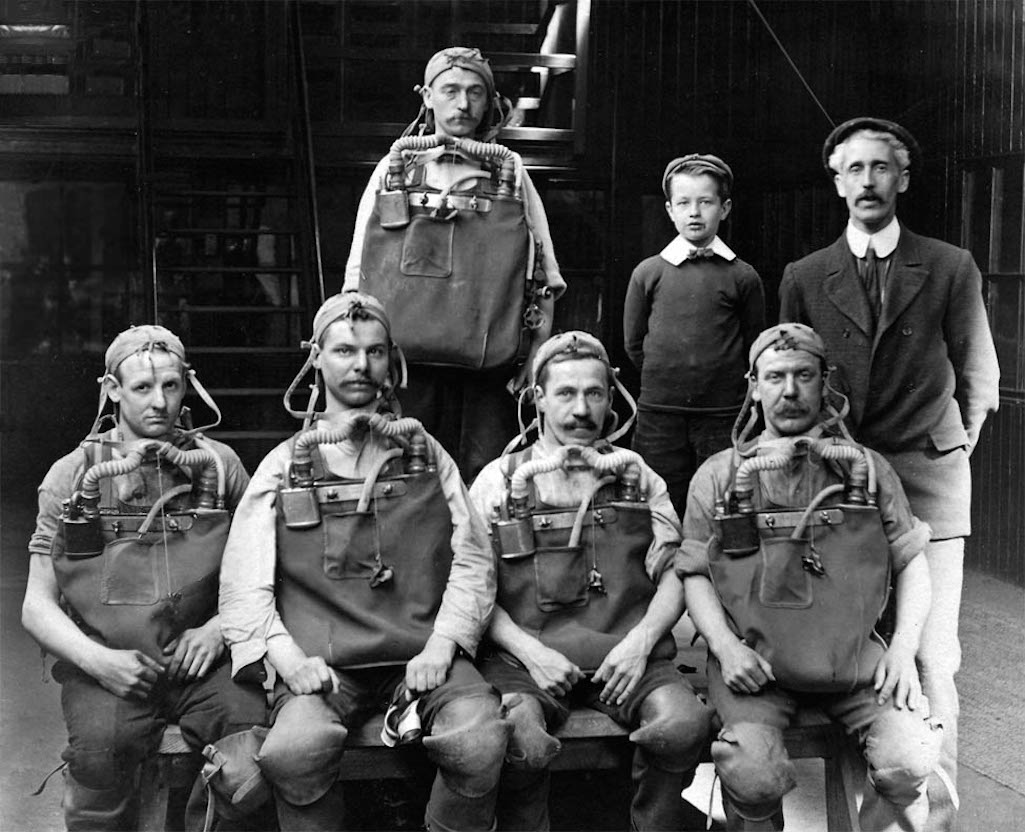

Then on December 21st 1910 at the Pretoria mine of the Hulton Colliery Company, just outside of Bolton / Atherton, a massive explosion killed 344 men and boys. Neither of these two collieries was owned by the Wigan Coal & Iron Company (WC & I), the owner of Clock Face Colliery, but they did make a significant contribution. Their six-man Rescue team from the nearby Westhoughton Colliery were highly praised for their rescue efforts in the Pretoria mine, working long eight-hour shifts under very difficult conditions.

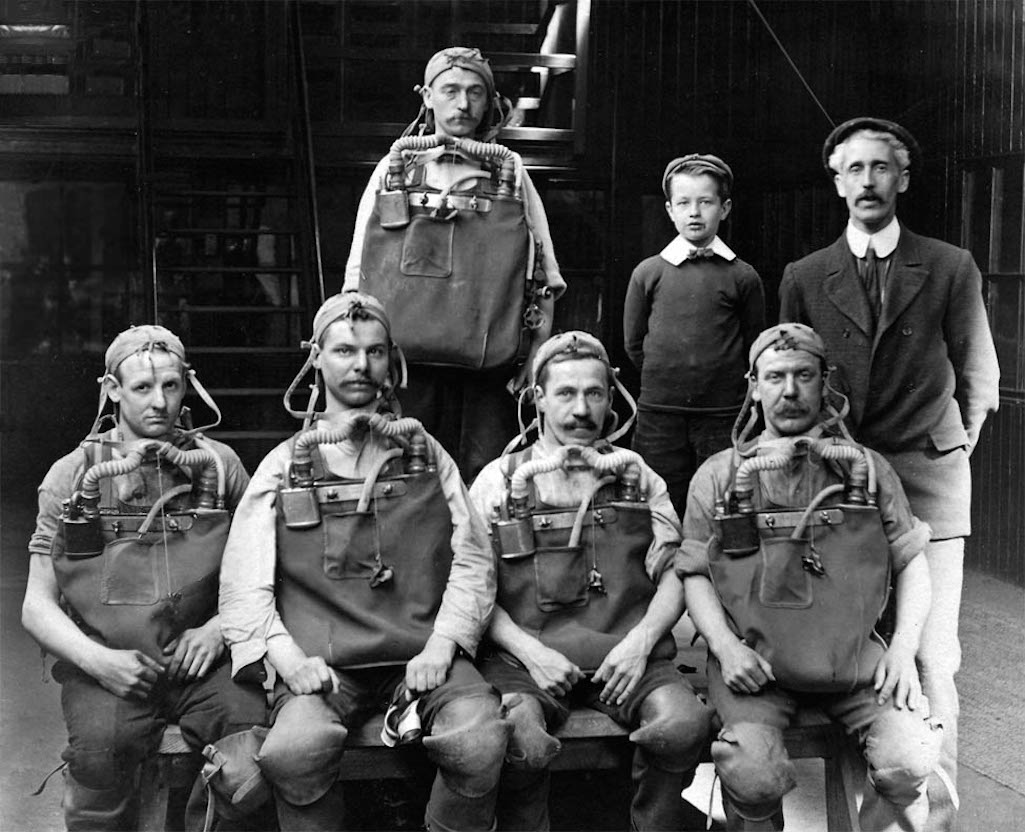

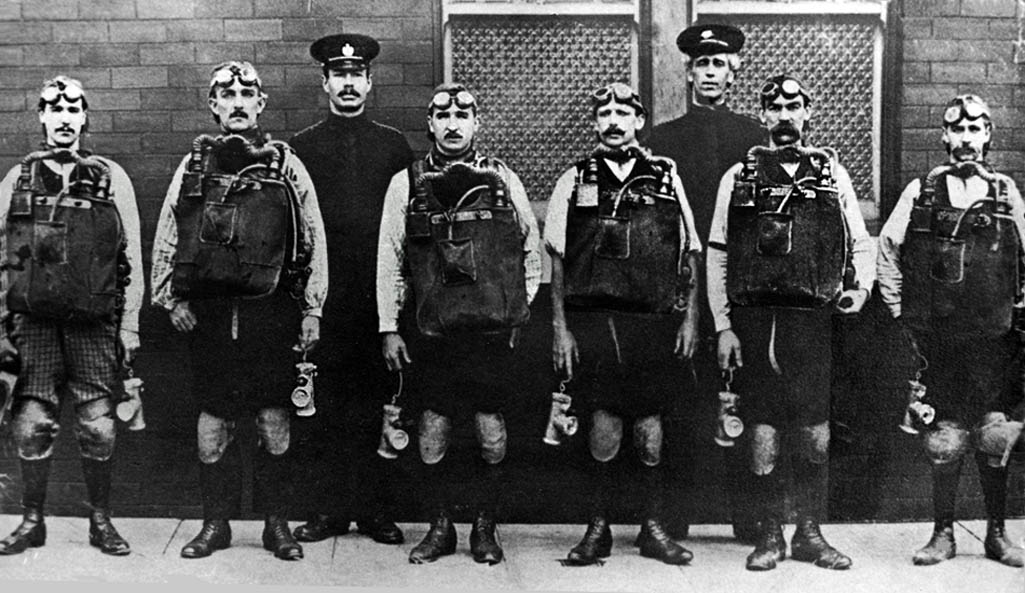

The Rescue Team unmasked with Frank Edmond seated 2nd from left - to his right is probably John O'Brien and driver Edwin Smith

The colliery Rescue Team unmasked with Frank Edmond second from left

Clock Face Colliery Rescue Team

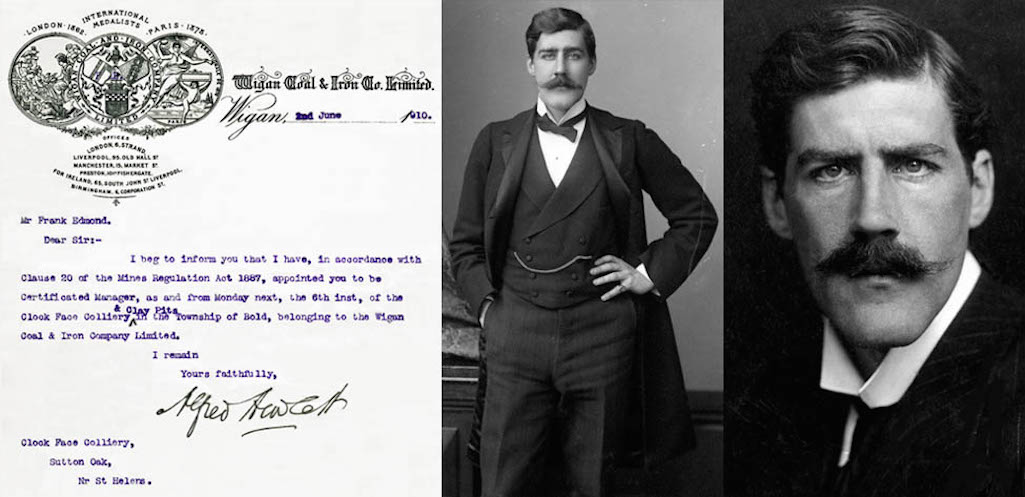

He was awarded the Royal Humane Society’s Hulton Medal for his rescue work in the Pretoria mining disaster and later said that if he were ever in a tight place, he would rather be in the company of a set of Lancashire miners than any other folk he knew. When WC & I introduced the rescue team to Clock Face, it is very likely that Frank was the individual personally tasked with demonstrating it to the selected members and was part of its early training.

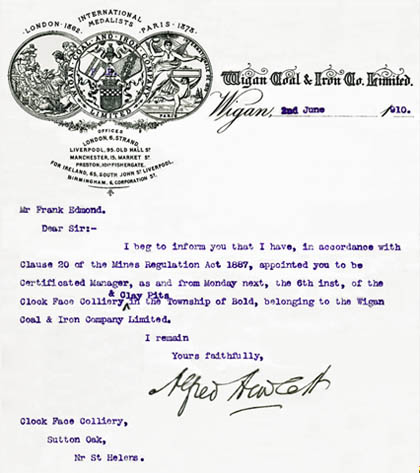

Left: Frank Edmond’s appointment letter from 1910; Right: Two photos of David Lindsay, Earl of Crawford

Frank Edmond’s appointment letter and the Earl of Crawford

Frank Edmond’s appointment letter

In 1929 Frank Edmond was appointed Agent of all the company’s Wigan collieries and in time he became the General Manager of all of their mines in Lancashire and Nottinghamshire. In 1934 Frank was appointed the company’s General Mines Manager and three years later became a member of the Board of Directors. In 1947 upon nationalisation of the mining industry he became General Manager of No. 2 (Wigan) Area in the NCB North West Division, until his retirement in 1951.

Four years earlier he had been awarded the CBE for his work on mine safety, having been a member of the Safety in Mines Research Board for a number of years. His main interest had been in the mechanics of roof control, with many mineworkers at Clock Face Colliery and elsewhere being killed and injured by collapsing pit roofs underground. Frank Edmond was also a key figure in mining education, having been a member of the Wigan Technical College board since 1912. Even though he was only at Clock Face as manager for a short time, he had clearly influenced its operations beforehand as a member of the rescue team and for many years afterwards through his managerial responsibilities.

In the Pretoria mine disaster a number of the dead had not been injured by the explosion, but had slowly succumbed to a lack of oxygen. With explosive gas being an important issue in many mine accidents, for any rescue brigade to have any success it was necessary to provide them with portable breathing equipment that would maximise their manoeuvrability in difficult situations.

The Proto Rebreather Apparatus became the standard kit for brigade use and was fitted over the wearer's head. It then rested on his shoulders and was held in place by straps around the waist. The oxygen supply was around two hours depending on the cylinder numbers and size, and whilst the unit allowed freedom of movement it was considered bulky, heavy, and in confined spaces within a mine, rather unpleasant to wear. In the photographs the important use of goggles is seen together with electric hand lights, good boots and knee pads. These are particularly important when crawling around in low, confined spaces.

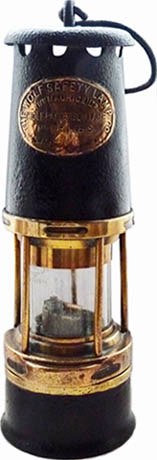

Other Home Office directions relative to the application of the Act at each Colliery Rescue Station were: a) Provision and maintenance of two or more small birds or mice for the testing of the presence of carbon monoxide gas. Most readers would be familiar with the long established practice of mines using canaries. b) Two electric hand lamps always ready for use and capable of providing its designed light standard for 4 hours. c) One set of oxygen reviving equipment. d) A safety lamp for each member of the brigade capable of testing for the presence of gas. e) An ambulance box provided by the St John Ambulance Association, or similar boxes, together with antiseptic solution and fresh drinking water.

So when we look at the Clock Face Rescue Team in the above photographs, do spare a thought for the history of the establishment in the first place, but also for the physical and psychological demands that the work placed on each member.

Like all pits, Clock Face Colliery had its share of industrial disputes. Some were national strikes, others were regional or localised disputes, such as in 1910. Then the near-200 men at Clock Face struck for quite a number of months from February, over revised working conditions and a pay dispute. The miners were offered 2 shillings a ton but they demanded 2s 4d, in line with what they claimed was the going rate at neighbouring pits.

In September 1910, men employed at the Wigan Coal and Iron Company's thirteen other pits, voted 2:1 to go out on strike in sympathy. However the result of the ballot was just short of the required 2/3rd majority that authorised a walk out. Frank Edmond became manager at Clock Face during the dispute and some years later made a note summing up his time in charge in which he wrote: “Got pit working after a long strike”.

The weighing took place via a weighbridge situated outside a wooden cabin that housed the actual mechanical scale. Each box of coal was positioned on the weighbridge, which was connected to the scales inside by levers. The weighman was able to determine the total load on the bridge by sliding a weight along the graduated lever until it was in a balanced horizontal position. He would then subtract the weight of the box to give the weight of the actual coal inside it.

After a strike the Wigan Coal & Iron Company and the men at Clock Face had agreed on a pay rate of 2 shillings a ton, with a guaranteed minimum of 7 shillings a day for all workers. Those miners who didn’t earn more than 7 shillings argued that they had no need for a checkweigher, so wouldn’t pay Lot Kitts. He argued that they had all agreed to pay him, so Kitts sued the refuseniks. Judge Shand ruled that he was fully entitled to receive payment from all the miners, whether they needed his services or not. The Check Weighbridge at Douglas Bank Colliery in Wigan is shown here in 1890. It provides a good illustration of the efficient organisation, with the weighman inside and the extra people required to quickly get the boxes on and off the weighbridge.

Harold Whitehead the manager of Clock Face Colliery during World War 1 - contributed by Brian Legg

Harold Whitehead the manager of Clock Face Colliery during World War 1

Harold Whitehead manager during WW1

The new club cost £2,000 and contained a large meeting room that measured fifty feet by twenty-two feet, a large billiards room and games room plus dressing rooms and baths for football and cricket teams. Newspapers reported how it was part of a scheme for a 'model village' that the company was creating with the Institute situated between football and cricket grounds and surrounded by new colliery houses. These fields as works in progress are shown in the Clock Face Sports photographs that are pictured below.

An unusual prosecution took place on March 10th 1914 when mine inspector George Fillingham found himself in court. He’d accompanied the manager Harold Whitehead on an inspection down the pit then realised he had his pipe in his pocket. Fillingham ran back to the cage and went straight up the pit but the damage had been done. The Wigan Coal & Iron Company had a rule that all who breached their 'no smoking materials' ban had to be prosecuted. However the magistrates dismissed the case on payment of 6 shillings costs. Fillingham was actually appointed by the miners who had been empowered by a 1911 Act to have a representative who would inspect the mine workings on their behalf.

Like most pits, there were many accidents and inquests into mining fatalities were often held at the Clock Face Inn. On January 21st 1915 Peter Brookfield of 37 Hall Street, Clock Face died as a result of a chain breaking and striking him a violent blow to his neck. The 18-years-old haulage hand collapsed in the arms of a colleague, saying "Give me a drink; I am choking".

Then on the 25th November 1916, 55-year-old John Gutteridge of Clock Face Road died as a result of a roof fall. A ventilating cloth fastened to a bar and some props had come loose and got caught in a coal wagon. This dragged the bar down, causing the pit roof to collapse. In September 1917 the Wigan Coal & Iron Company opened Clock Face Colliery School on a site near to the mine, which cost them over £5000. The four foundation managers with responsibility for the new school included William Sword, manager of Clock Face Colliery, and John Pickett, one of his colliery undermanagers.

One of the stupidest things a miner could do was take matches underground. The danger of a gas explosion was ever-present and those who were caught with matches were prosecuted. William Unsworth of Hoghton Road and John Henry from Mill Lane in Sutton were each fined £2 in St.Helens Police Court on the 12th February 1918 for committing that offence down Clock Face Colliery. Both told the court that it had been an accidental occurrence and realised the seriousness of their offence.

Some Clock Face workers took a long time to succumb to their injuries. Evan Davies of 27 Rolling Mill Lane, Sutton was run over in October 1917 by the boxes of coal that he was lowering down a brow. However he didn't die until June 2nd 1918. William Whittall of Leigh Terrace, Clock Face Road, was fatally injured on January 22nd 1919. The surface hand was engaged in lowering wagons of slack when a brake lever struck him in the region of the heart. Whittall died on the following day just weeks after returning to civil life after prolonged army service in France. On four occasions he had been wounded and had spent nine months in hospital in Glasgow.

On January 23rd William Glover of Clock Face Road was, like Evan Davies, killed by runaway coal wagons. Glover had heard the sound of two empty wagons (a.k.a. boxes) coming towards him and attempted to escape down a hill. However the runaways struck three stationary wagons and a tram of timber and all were forced down the hill in the direction of Glover. William Huxley found his colleague dead on the ground. At Glover’s inquest at the Clock Face Hotel, under-manager John Pickett of Gorsey Lane said he could not explain why the deceased had chosen to run down the hill. If he had stood still or moved two yards to one side, the man would have been safe.

John Quinn from Jersey Street in Clock Face died in St Helens Hospital on the 23rd, thirteen days after injuring his thumb in a roof fall. The thumb became septic but at the 55-year-old’s inquest, it was stated that the cause of death was sudden heart failure due to the diseased condition of Quinn’s heart. January 1919 was a particularly bad month for accidents at Clock Face Colliery. Garratt Murray also lost his life during that month having been struck down by a roof fall.

It's surprising how many mineworkers felt that sleeping down the mine was a good idea. On August 12th 1919 two Sutton youths appeared in court charged with being asleep while below ground. William Grimes and Phillip Garvis worked at Clock Face and they had been sleeping for almost an hour before being roused. One was sleeping in an underground roadway and any coal tub that was sent down would probably have killed him. The other was lying with his feet against the rails on which the tubs were propelled down and could have had them cut off if struck by a tub. It was stated by the prosecution that sleeping had become a common problem in the mine and warnings had been made that were not being heeded. Both were given hefty £5 fines or if in default serve 28 days in prison.

On October 4th 1919 Joseph Brown died at his home in Derbyshire Hill Road four months after fracturing his spine down Clock Face Colliery. The pit contractor was undertaking roofing work with his back to the coalface, when a piece of coal, 7ft long and 3ft 6 inches wide, fell and struck him in the back. Joseph was in hospital until a month ago, when his wife requested that he brought home.

There was a curious case in the St Helens County Court on October 15th when the owners of Clock Face Colliery sued a former employee. The Wigan Coal & Iron Company claimed that Thomas Francis had been paid £2 14s 7d too much after undertaking five days temporary work. Clock Face Colliery had two separate pay offices for their underground and surface workers. After completing his week's labour, surface employee Francis had gone to the office for underground staff and presented his pay tally. This bore the number 130 and he was handed £5 4s 8d. Later the underground worker with the same tally number went for his pay and was told it had already been claimed. Once the mistake was realised the manager of the mine, William Sword, sent for Thomas Francis but he refused to see him. The judge in the court gave judgement for the amount claimed but said the way they paid their wages in the mine was an "exceedingly risky one".

Two days later Thomas Atherton of Mill Lane in Sutton was fatally injured down no. 2 pit. The day wage man (a.k.a. dataller) had been sawing a wooden prop to put under a stone in the pit roof. Rather foolishly Atherton and a man called Patrick O’Brien, chose to saw the prop while standing directly underneath the stone. It suddenly fell on Atherton and he died four days later in St Helens Hospital. At the man’s inquest at the Town Hall, the coroner Samuel Brighouse was highly critical of O’Brien, after he said they hadn’t expected the stone to fall. "Familiarity breeds contempt", remarked the coroner, adding that he’d often heard this complacent attitude given in evidence at colliery inquests.

On January 21st 1920 James Whittaker was killed while walking on the surface of Clock Face Colliery. The 18-year-old lampman from Station Road in Sutton was killed by a train running wagons laden with dirt towards a tip. This was despite the engine driver repeatedly blowing his whistle at the young man.

"Whirled To Her Death – Girl’s Terrifying Experience", was the headline to an article in the St Helens Reporter on the fate of Mary Corbett at Clock Face Colliery. The 17-year-old from Jersey Street was killed on March 4th 1920 while working on the colliery screens. This was a section of the mine where dirt was removed from coal and where it was sorted by size. There was a problem with a strap underneath the conveyor belts and Elizabeth decided to poke it with an iron bar. Ellen Derbyshire from Crawford Street told her to leave the strap as it was dangerous, which Elizabeth did. However the shafting caught her clothing and whirled her round at 70 revolutions per minute. Within a few minutes of being freed from the machinery, Elizabeth had died.

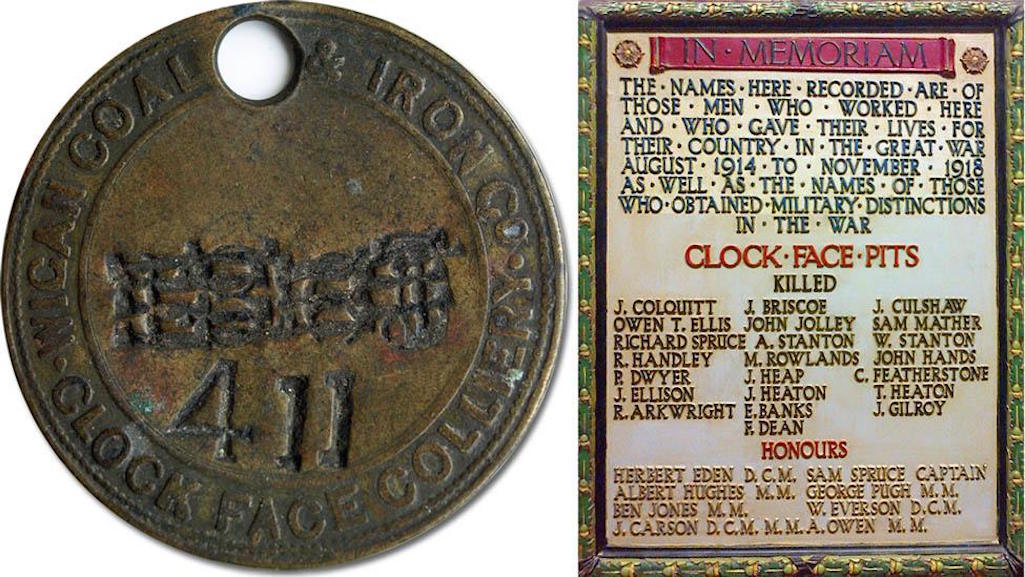

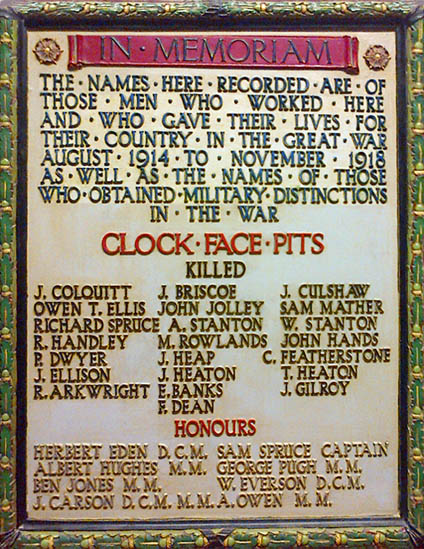

Left: An old Clock Face Colliery tally; Right: Plaque in Clock Face Miners Recreation Club

Left: Colliery tally; Right: Plaque in Clock Face Miners Recreation Club

Plaque to Clock Face hero miners

John Fenny of Hall Street in Clock Face was instantly killed on September 24th 1920 down no. 3 pit while fixing a prop to the roof. About a ton of debris fell on top of him and it took rescuers about 40 minutes to extract him. George Simcock from Abbotsfield Road in Sutton was killed on October 11th 1920 as a result of a roof collapse. Those who were alongside him jumped out of the way of the falling earth and escaped injury. As Simcock was being rescued, a second larger fall occurred that completely buried the 38-year-old in tons of debris and it took eleven hours to extricate his body. Then on November 24th 1920 an inquest was held on Bernard Ryan from Fairclough Street in Burtonwood who had died as a result of a heavy stone falling onto his back.

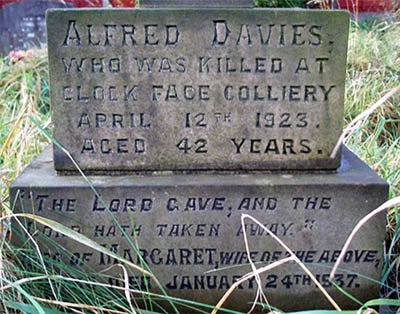

Alfred Davies grave at St. Nicholas

Roscoe was now an insurance agent but had been the district president of the Miners’ Federation during the strike. During a hearing in St.Helens County Court on February 7th 1923, it was alleged that the colliery company were being vindictive. Judge Dowdall seemed to agree and refused to make an order to turn Roscoe and his family out, saying that the Wigan Coal & Iron Co. would first have to find them alternative accommodation.

G. B. Tristram was listed as manager in the 1923 edition of the Wigan Coal and Iron Co's Colliery Year book. This also revealed that Clock Face's nos. 1 and 2 pits had 475 workers (underground and surface) with no.3 pit having 819 workers underground and 204 on the surface.

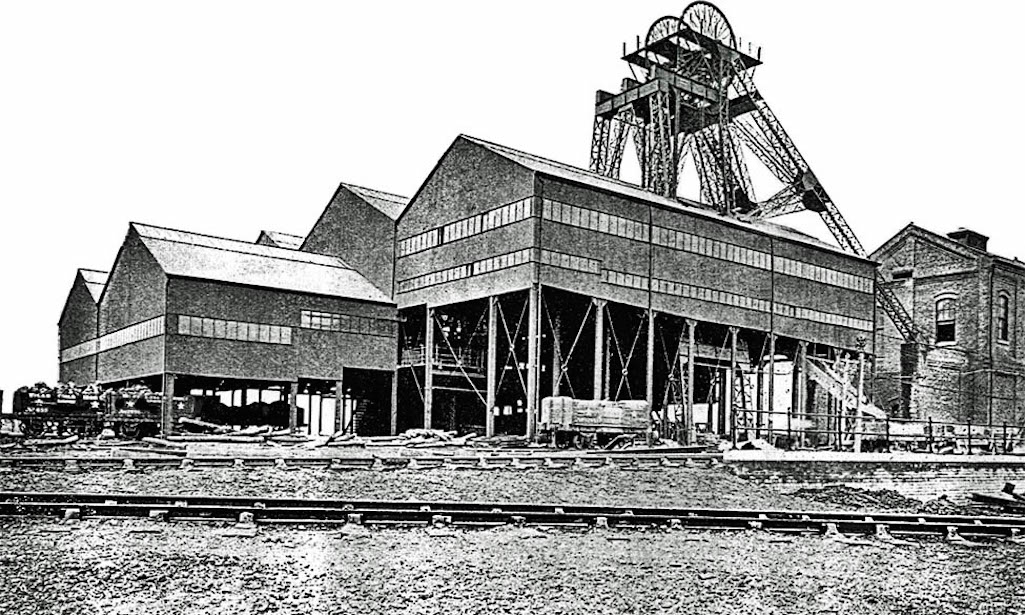

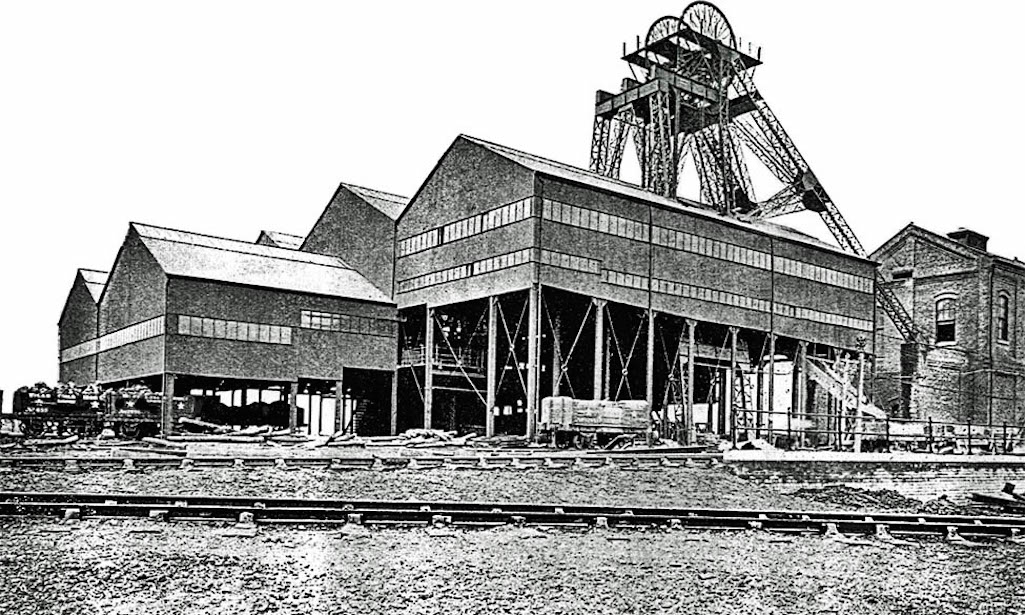

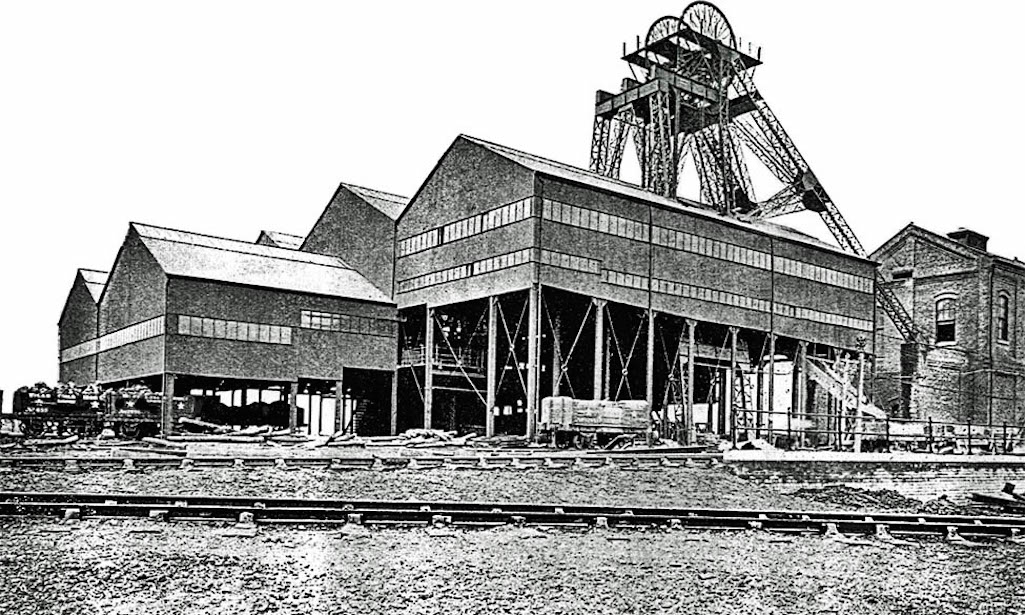

Headgear, screens building & winding house (right) of no. 2 downcast pit of Clock Face Colliery during the 1920s

Headgear, screens building and winding house (right) of no. 2 pit in 1920s

Clock Face Colliery during the 1920s

That is with the exception of two men who are putting on sheeting and installing windows into the 'screens' building. They are stood on what appears to be a single plank without rails or protective helmets. Occupational health and safety during the 1920s was not what it is today! A rare day with no production was an ideal time to perform such tasks. When mining operations were underway, the whole building would shake from the vibrating screens and shakers, which is not good for new glass. The top photograph also shows rope coming out of the winding house on the right of the picture. Ebor Rowley from Leach Lane, who was a member of St. Nicholas church choir, was for many years a winder at the colliery until its closure. Like other winders in pits, Ebor would sit alone responding to the shaft signals.

The screening process was an important part of mining and it's worth describing its function and the processes and technologies employed at Clock Face in some detail. Screening or sorting was required because the material that came up the shafts in the 'tubs' (skips in Parkside and from 1986 in Sutton Manor) was not just coal. It also included rock, plus discarded items used in maintaining miners' safety, eg. timber, steel bars and brattice cloth used in ventilation. The coal also varied in size and type and burning efficiency.

Pictured from Gorsey Lane with Sutton Manor to the right. No. 3 pit's headgear on the left of picture is being dismantled, ready for replacement with steel headgear of similar design to no. 2 pit on the right which is integrated with new screen building

No. 3 pit's headgear on the left is being dismantled ready to be replaced

No. 3 pit's headgear is being dismantled

It was also necessary to remove the aforementioned redundant items, such as timber and brattice cloth, so they could be recycled or disposed of. In the early days, these products were crudely extracted before they got into wagons or coal sacks. This hand separation work was mainly carried out by women and it was slow, tiring work. Developments in the efficiency of underground extraction, the opening of multiple coal seams and improved winding speeds and techniques led to greater volumes being wound and so improved screening methods were needed.

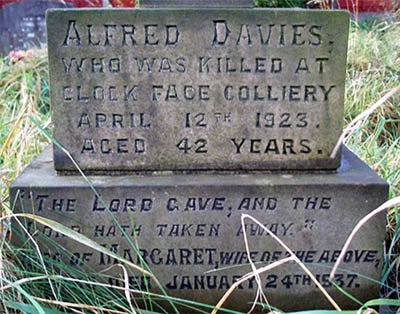

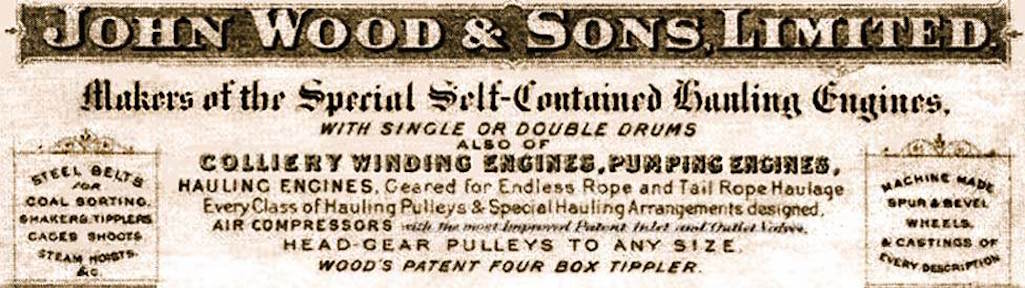

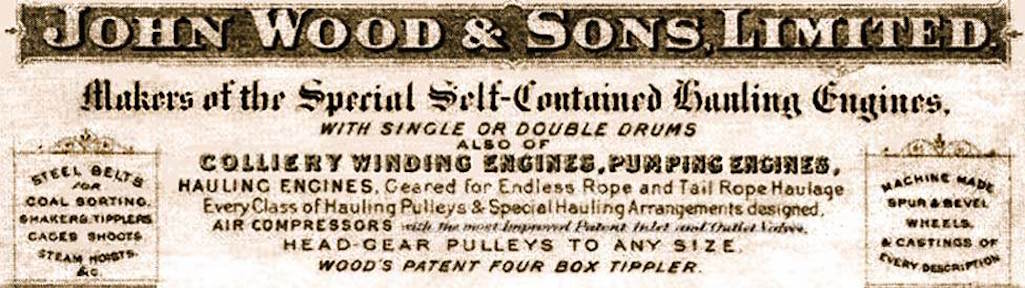

The letterhead of John Wood & Sons Ltd. who designed and made the screens at Clock Face Colliery

John Wood & Sons Ltd. designed and made the screens at Clock Face Colliery

John Wood & Sons Ltd. designed and made the screens at Clock Face Colliery

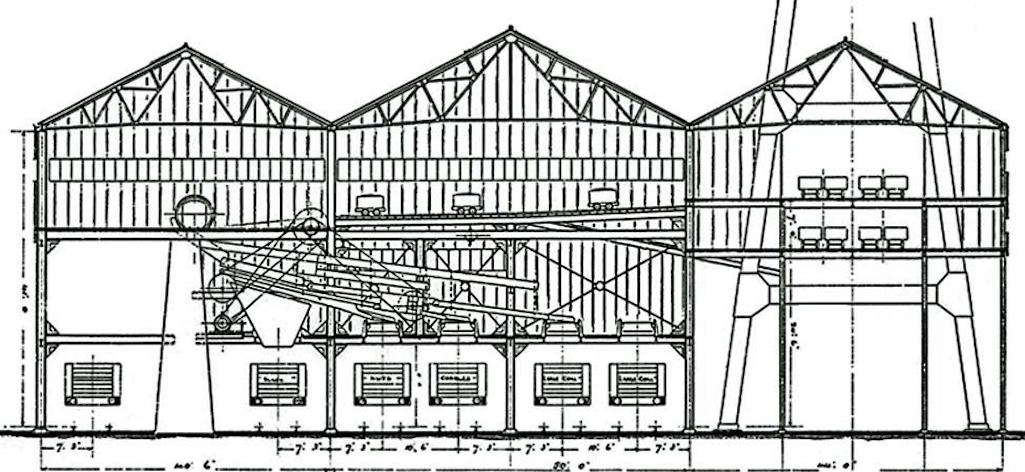

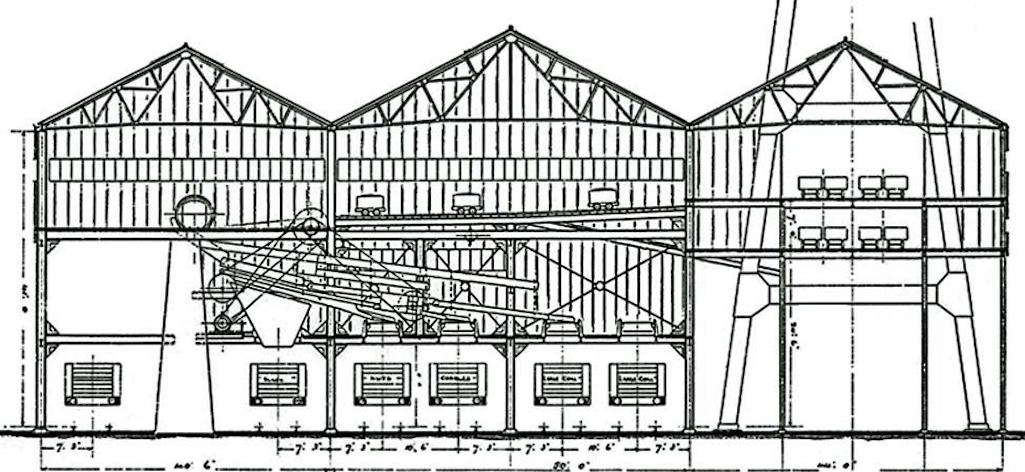

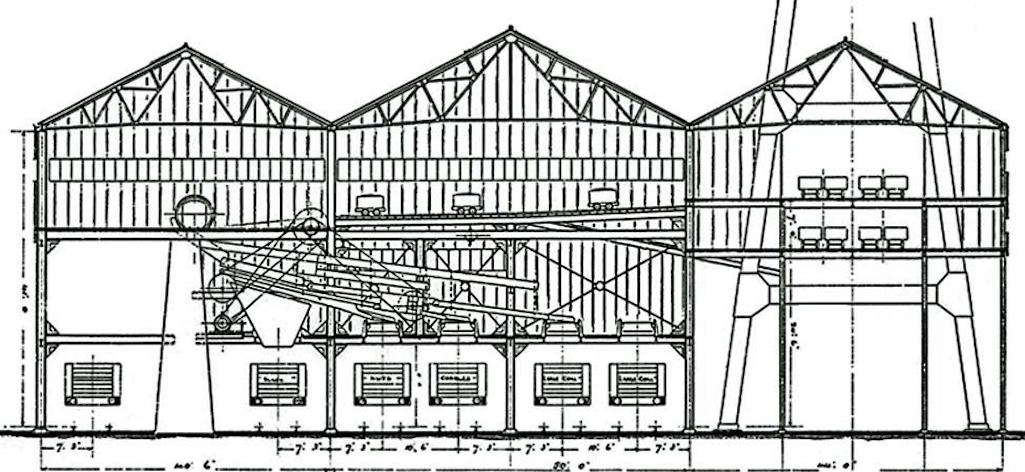

Both the horizontal and vertical separations ended via chutes into rail wagons underneath. When all these drops in levels are added together, it can be appreciated that the original surface stopping level for the cages in the shaft now had to be much higher. Coupled with the introduction of overwind safety devices into the headgear, to stop the possibility of the cage going over the pulleys, these changes required complete new headgears to be installed or existing ones modified. Clock Face Colliery covered all of these issues during the 1920s, illustrated in the following pictures.

Clock Face Colliery pictured in John Wood & Son catalogue - From the Graham Isherwood Collection

Clock Face Colliery as depicted in John Wood & Son’s catalogue

Clock Face Colliery as it was pictured in John Wood & Son’s catalogue

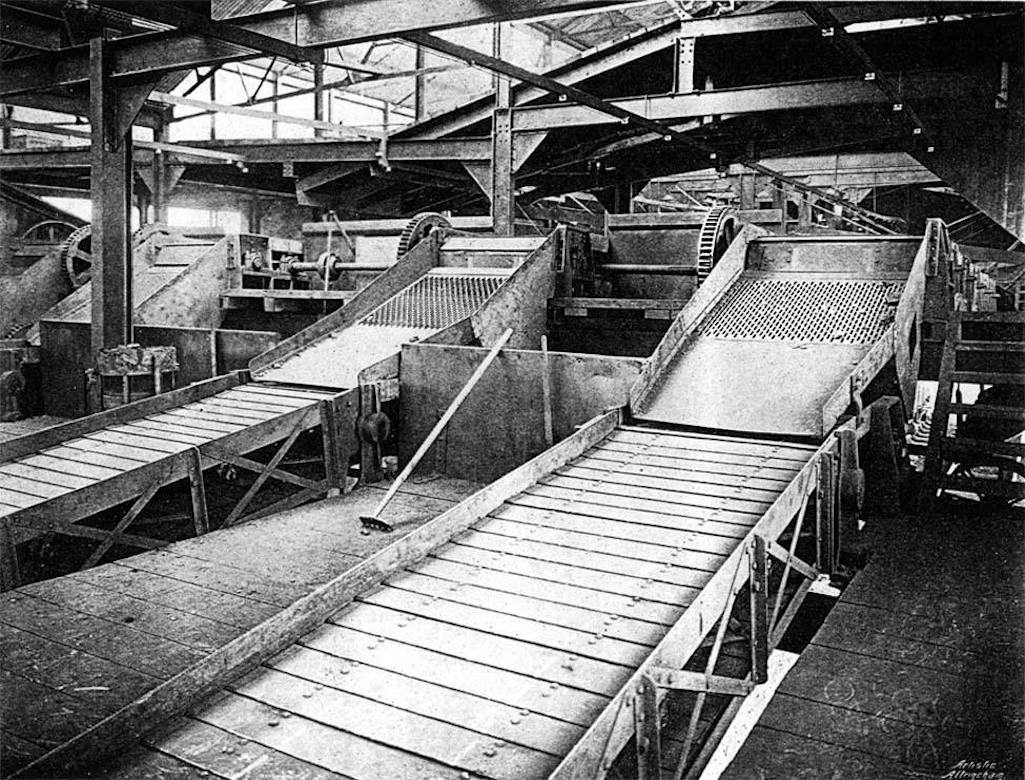

The screens building was a significant investment for the Wigan Coal and Iron Company and John Wood & Sons supplied the screening equipment. They included the photographs below in their catalogue which demonstrate the different stages of screening at Clock Face.

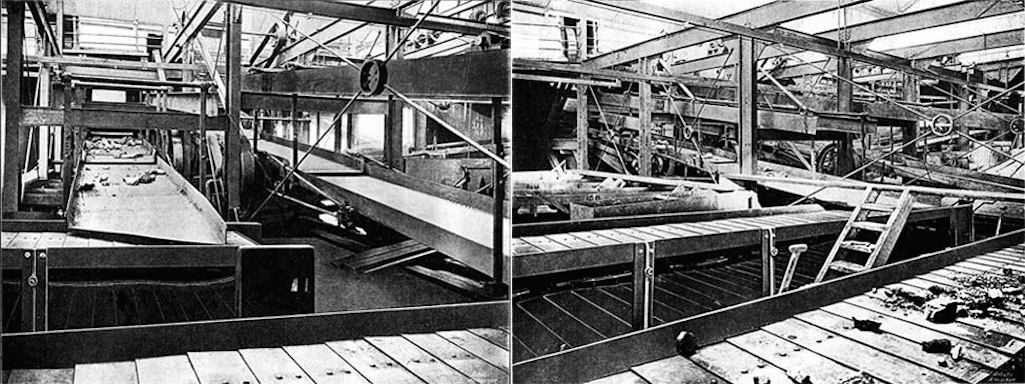

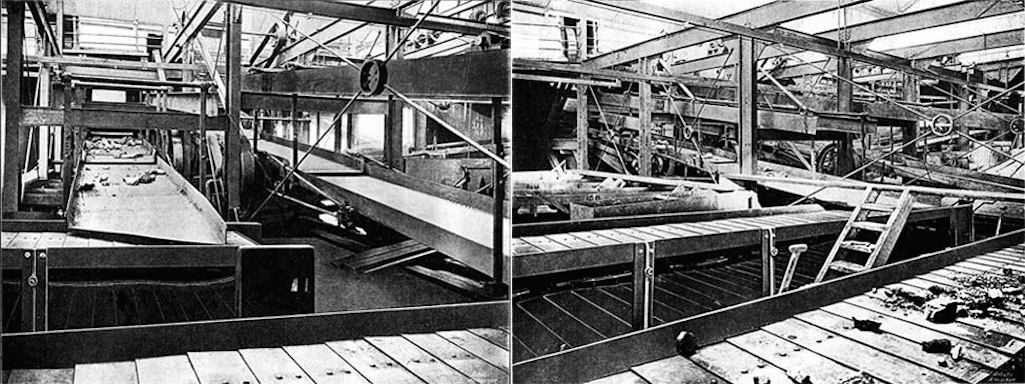

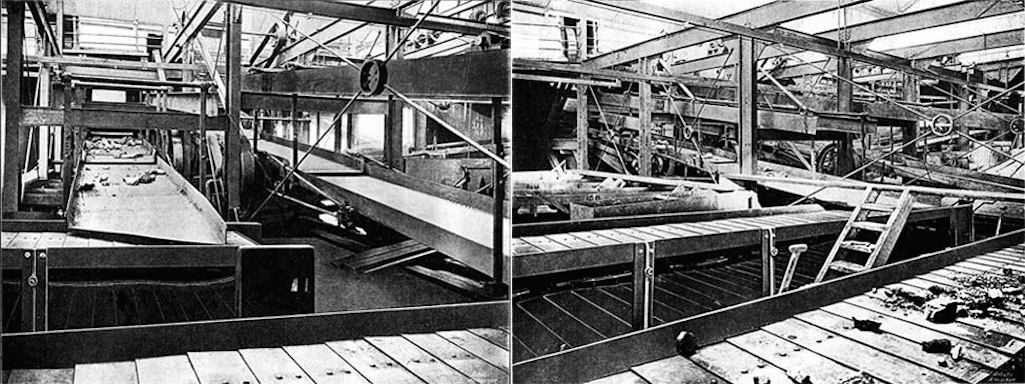

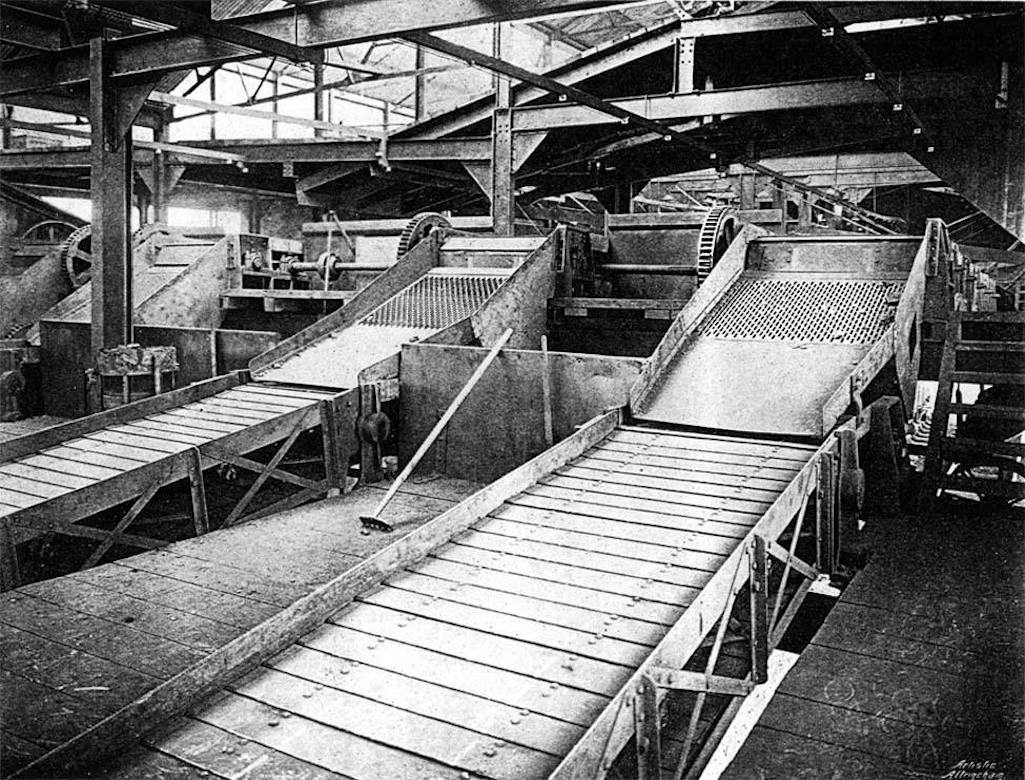

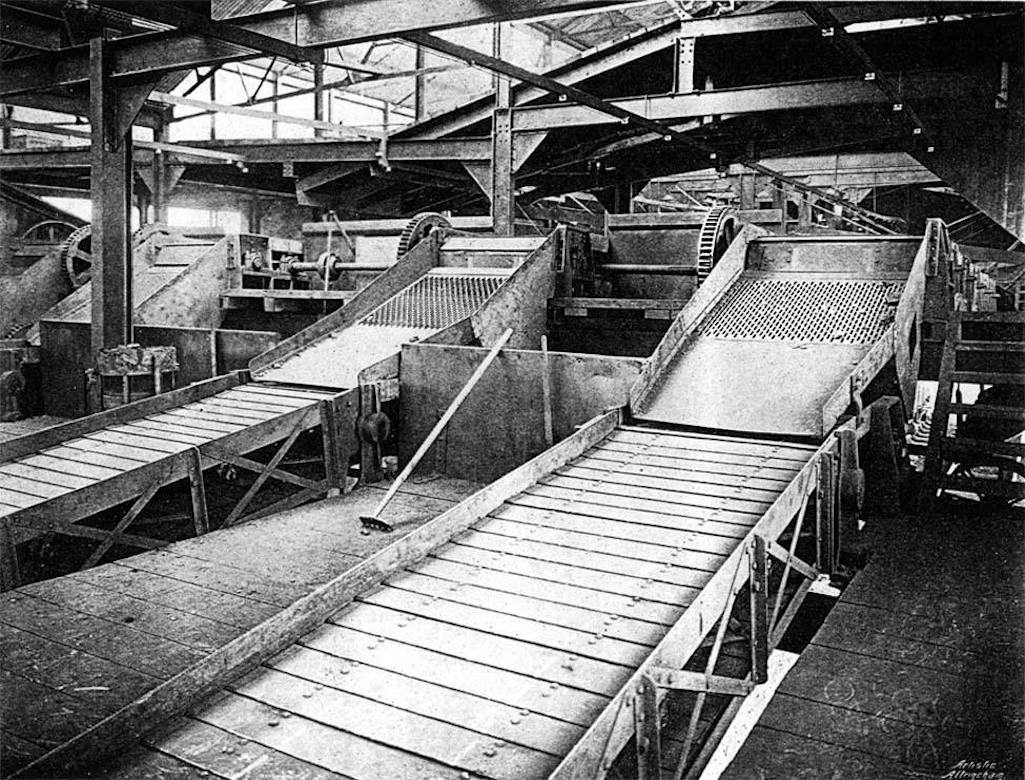

Two photos taken inside the Clock Face Colliery screens building - From the Graham Isherwood Collection

Two photos taken inside the Clock Face Colliery screens building

Inside the colliery’s screens building

The second photograph on the right shows the next stage with the slat conveyors taking the coal through a hand screening area. Women would generally stand alongside these conveyors to remove unwanted items, dropping them into a hopper between the 2nd and 3rd conveyors. Note the steps and platform used to cross from one position to another, and the shovels that were used in the removal process as well as to keep the floor clean. The small amount of coal on the conveyors suggest that the photographs were taken at the installation period during trials of the various stages of screening.

Inside the screens building pictured in John Wood & Son's catalogue - From the Graham Isherwood Collection

Inside the screens building pictured in John Wood & Son's catalogue

Inside the colliery’s screens building

Sectional drawing of the Clock Face screens building - From the Graham Isherwood Collection

A sectional drawing of the Clock Face Colliery screens building

Sectional drawing of screens building

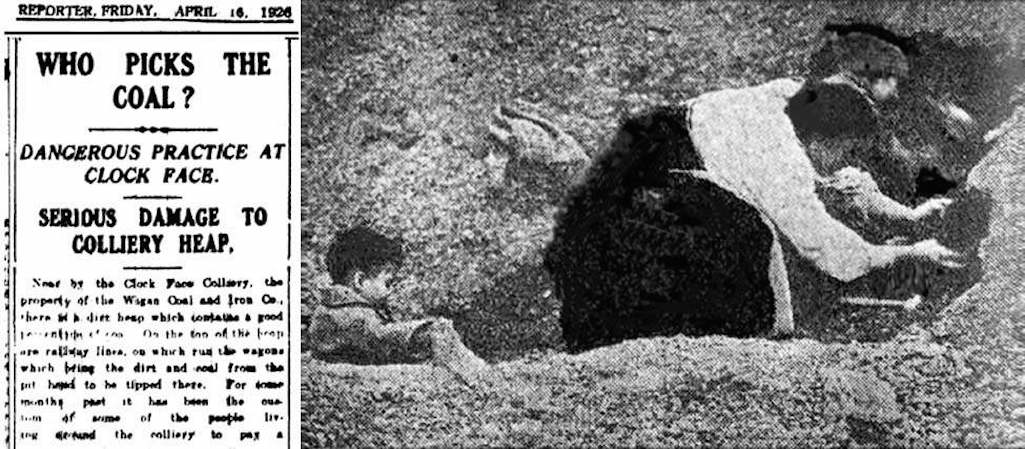

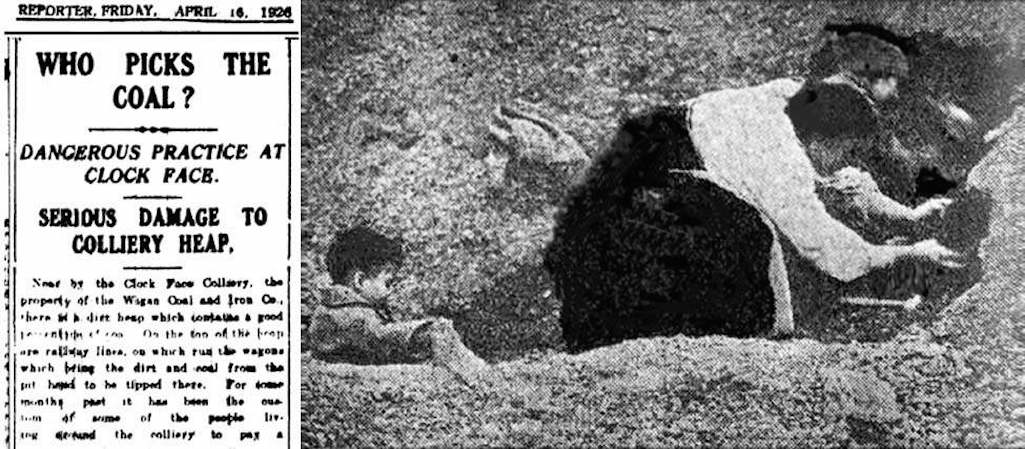

The strikes in the 1920s caused considerable hardship to the families of miners. Just days before the 1926 national strike and lock out, the St.Helens Reporter, in an article entitled 'Who Picks the Coal? - Dangerous Practice at Clock Face', described how serious damage had been caused to the colliery dirt heap by one hundred and fifty people who'd been helping themselves to coal. The article reported that it had been the custom for some months for local people to regularly visit the heap and 'purloin some of the coal which they found there'. The practice had continued despite the death of a man, which the newspaper described as a 'raider', who some weeks earlier had been buried alive whilst taking coal.

St.Helens Reporter 16/4/1926 and women picking coal at Clock Face during the 1926 lock out - note small boy on left

St.Helens Reporter 16/4/1926 and women picking coal during the lock out

Women shown picking coal at Clock Face Colliery during the 1926 lock out

Men preparing food for the soup kitchen at Clock Face in September 1926 during the miners' lockout

Preparing food for the soup kitchen at Clock Face in 1926 during the lockout

Preparing food for the soup kitchen in 1926 during the miners' lockout

Clock Face Colliery miners thought to have been taken during the 1926 lock out - contributed by Alan Mercer

Clock Face Colliery miners thought to have been taken during the 1926 lock out

Clock Face miners during 1926 lock out

There were exciting times ahead during the 1930s with the building of a baths complex, which also housed a lamp room, rescue station & first-aid room, cycle shed, offices and a canteen. You can read about this and much, much more in the second and final part of this comprehensive history of Clock Face Colliery.