An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 89 (of 95 parts) - History of Clock Face Colliery Part 2 (1930 - 1966)

Sutton Manor Colliery | Bold Colliery | Lea Green Colliery

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright & Harry Hickson ©MMXX Contact

Sutton Manor Colliery | Bold Colliery Part 1

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Old Sutton in St Helens

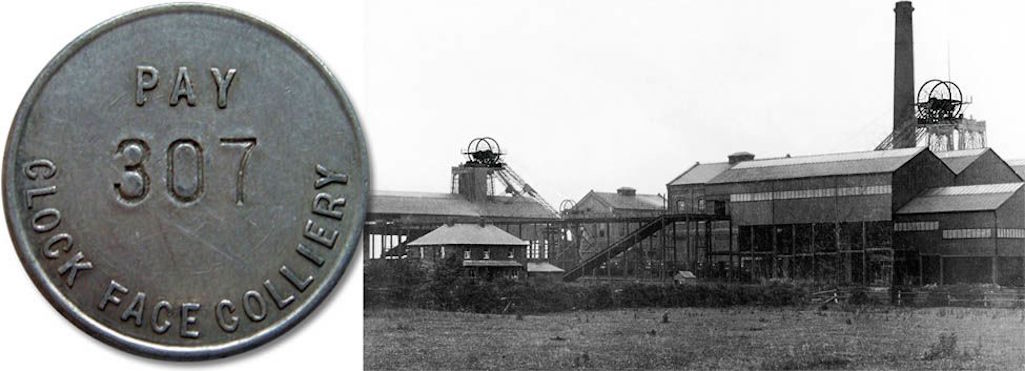

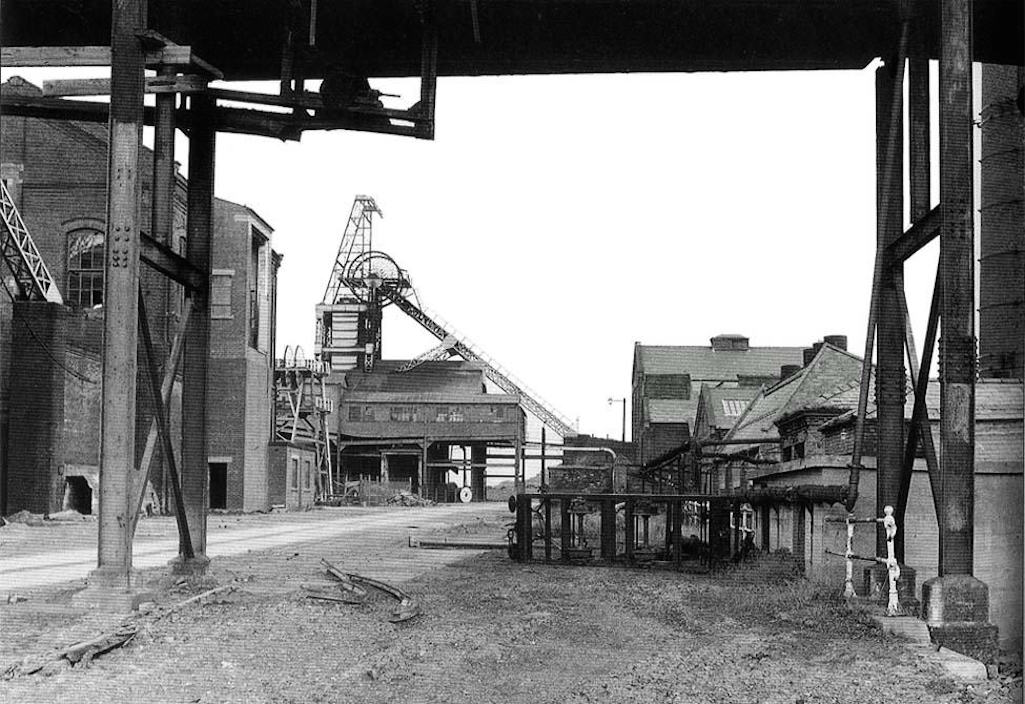

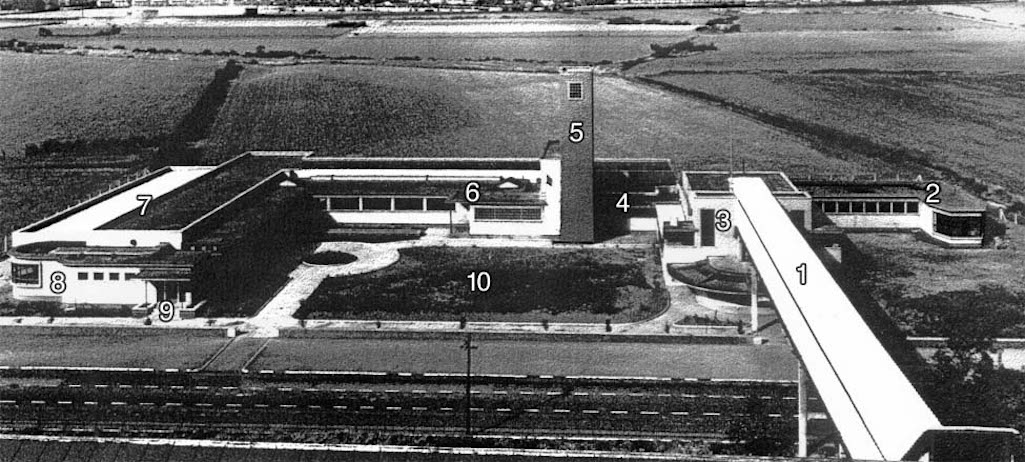

Left: Colliery Tally; Right: An undated photograph of Clock Face Colliery - probably taken during the 1930s

Colliery tally and undated photo probably taken during the 1930s

Tally and 1930s photo of the colliery

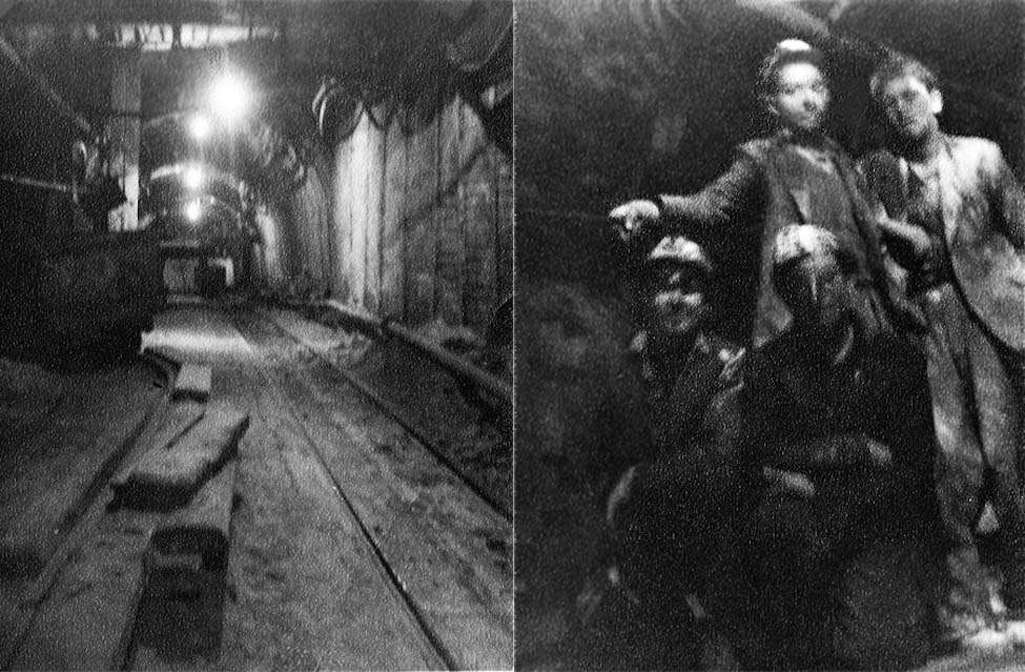

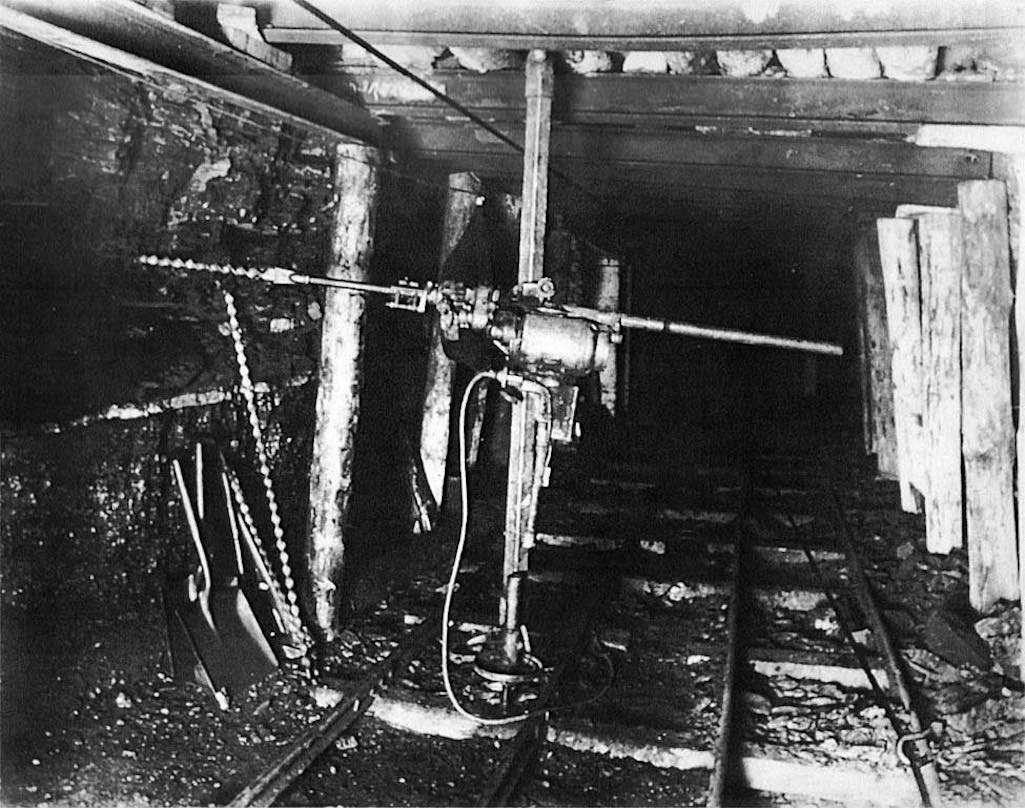

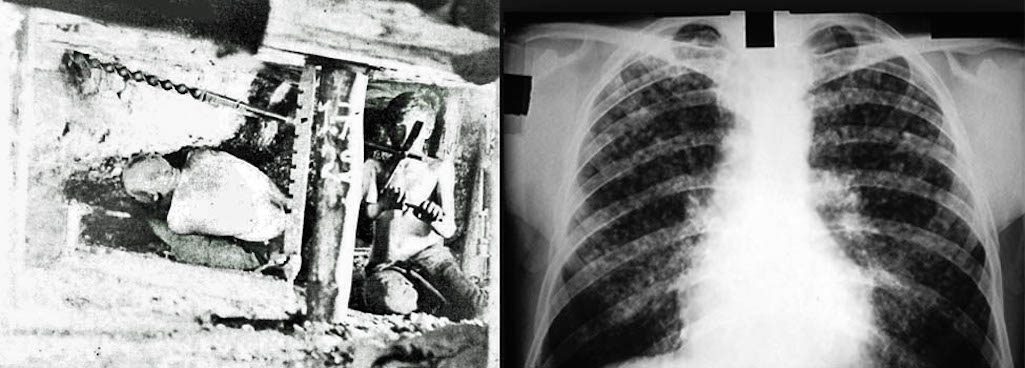

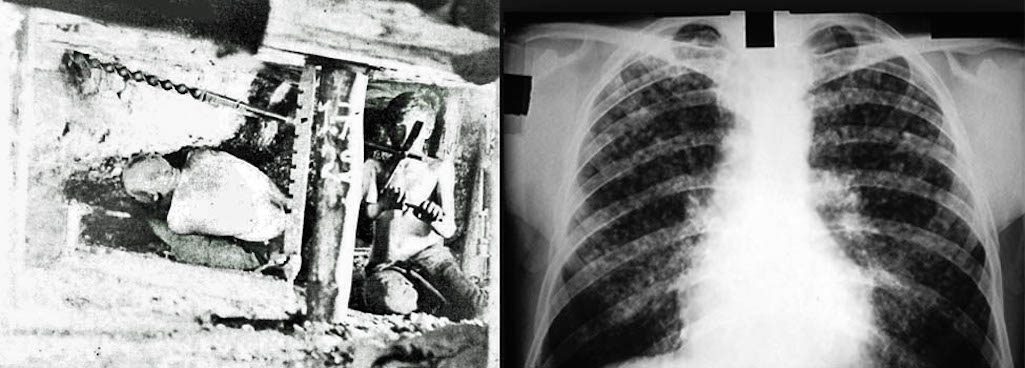

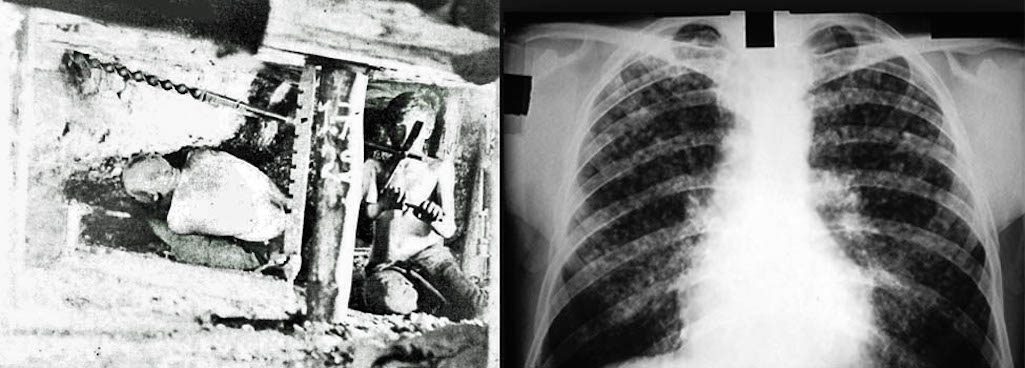

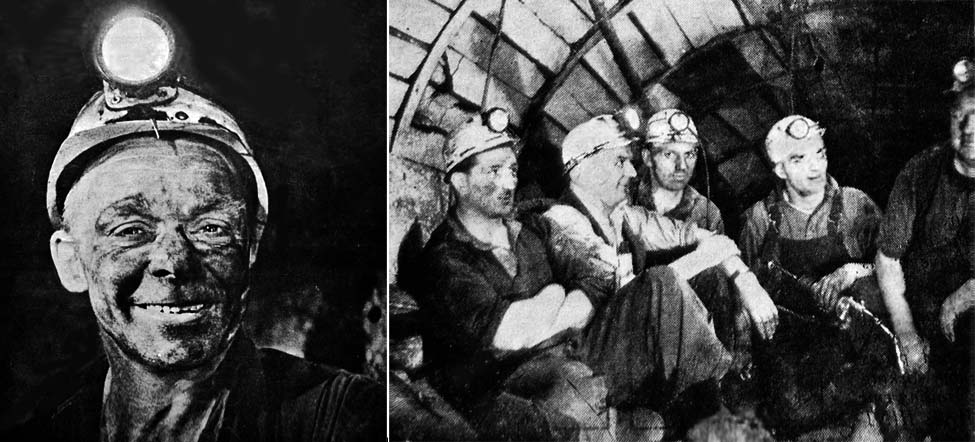

Cameras were not usually permitted at Clock Face so underground photographs are rare - contributed by Terry Callaghan

Two underground photographs at Clock Face Colliery, St.Helens

Underground at Clock Face Colliery

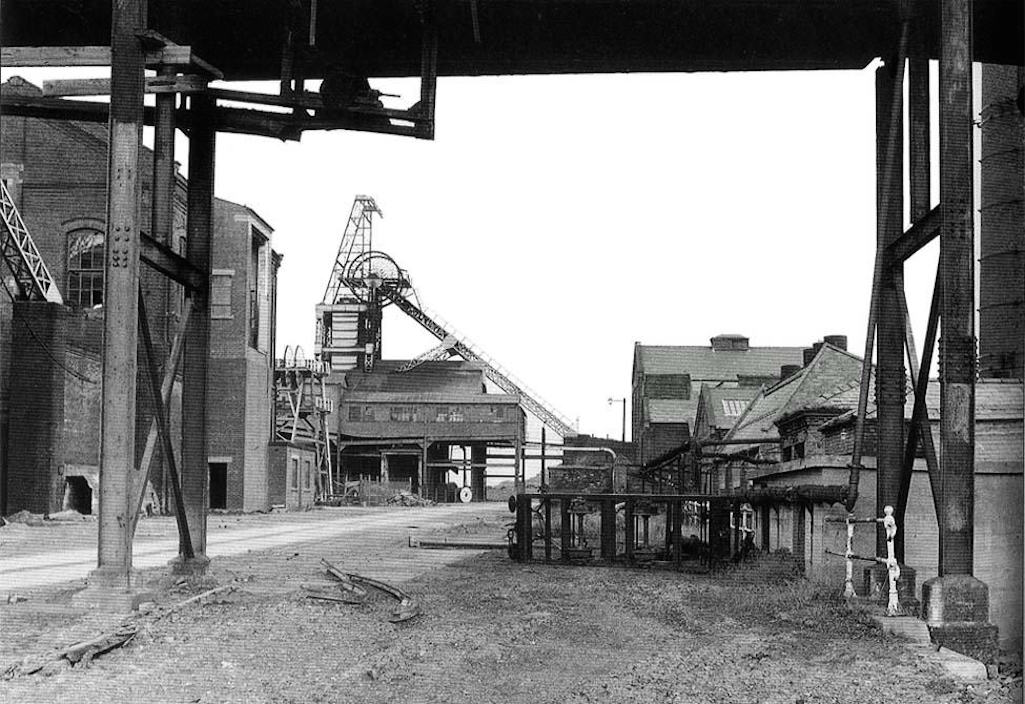

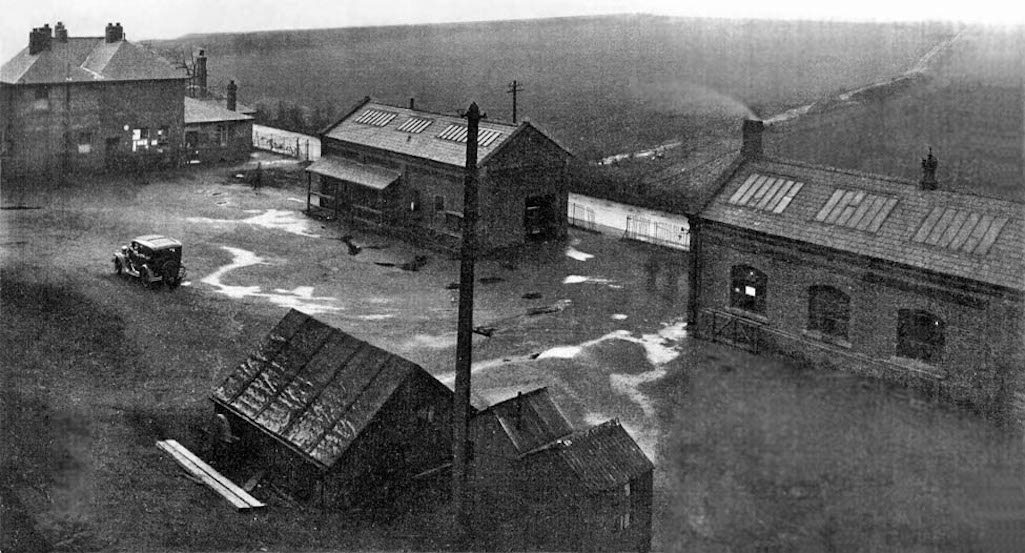

Clock Face Colliery headgears, screens and winding house (undated but the desolate scene suggests a strike day)

Headgears, screens and winding house at Clock Face Colliery

Headgears, screens and winding house

The winding house for the no. 1 shaft can be seen behind the building steelwork on the left of the photo. The small no. 1 shaft was the pumping shaft through which large volumes of piped water were brought up every day. This was through the work of large pumps contained within the pump house on the right of the picture facing the shaft.

On the extreme right of the above photograph, the lower section of the colliery chimney through which the boiler's combustion products were extracted, can just be seen. The boiler also produced steam for various colliery uses including heating the offices and baths etc. Some black-looking insulated hot water pipes from that location can also be seen on the right.

The drilling machine is well secured, having been set up to drill holes for the placement of explosive ‘shots’, in order to drive a new tunnel to the left. This is indicated by the free span of the top support bar above the drill, with the tunnel driven to open a new coal face running in that direction. Note the spare drills and very large flat shovels, specifically designed for more efficient clearing of the stone residue after the shots had been fired.

On June 1st 1935 the manager of Clock Face Colliery, T. W. Shaw, died while playing golf on Hindley Hall links, near Wigan. He appears to have been replaced by Herbert Price, who was certainly manager in 1939. On February 24th 1937, an unnamed miner was killed down the colliery after completing his normal shift and being told to undertake overtime. Joe Tinker MP raised the case in the House of Commons and Captain Crookshank, the Secretary of State for Mines, replied that there had been no contravention of the law. The usual coal cutter machineman had been absent through illness and so the miner who lost his life had simply been asked to deputise.

As stated earlier miners could take time to succumb to their injuries after suffering an accident and the death of Charles Thompson of Gartons Lane in Providence Hospital on January 26th 1939 took place seven years after he’d been hurt. Six weeks later at a meeting of Whiston Rural Council it was stated that Gorsey Lane was subject to flooding whenever there was heavy rain. As a result the colliers at Clock Face had to wade through two feet of water to reach their bicycles after finishing work. A surveyor told the meeting that the flooding was due to a lack of surface water sewers.

The manager’s family occupied the left half of the building and its upstairs bedrooms, with the office on the right, which included personnel involved in land sales, timekeeping, pay etc. The brick building to its right along Gorsey Lane, with the porch over one side is likely to have been the colliery lamp/tally room. At the end of the building you can just see the rear of the vehicle, which was used by the colliery safety/rescue team to take injured personnel to hospital, or assist in colliery incidents. The longer building to the right would likely be the building that housed the rescue team's equipment, as well as its specialised simulated training facilities, which were discussed in part 1 of these pages.

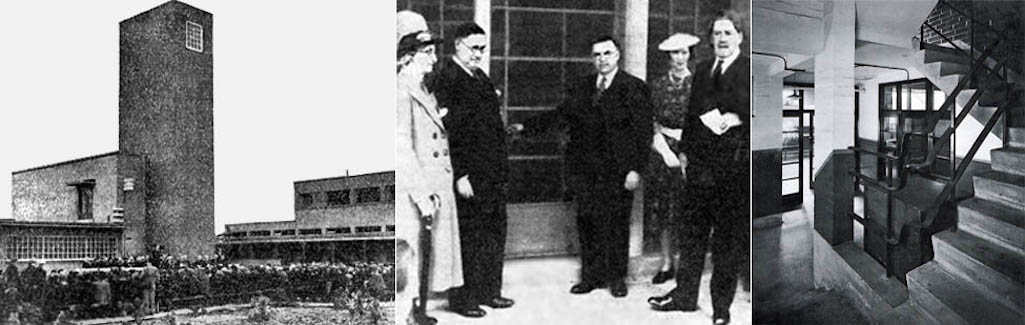

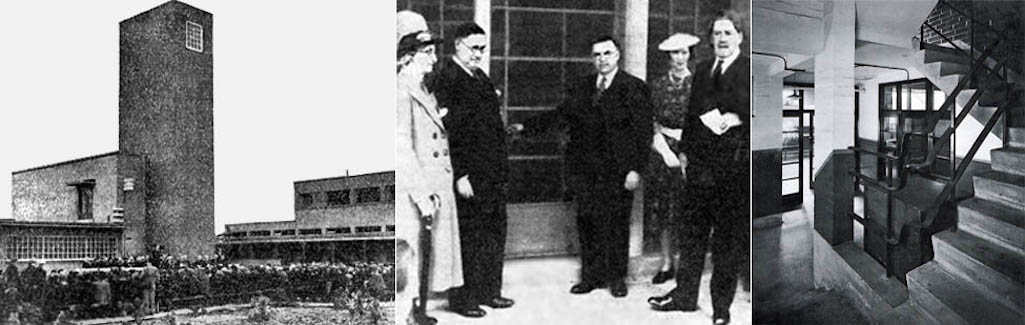

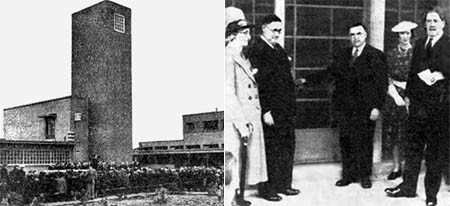

Two photos of the opening of the colliery baths complex and an interior picture of its entrance

The opening of the baths complex and an interior photo of its entrance

Opening of the colliery baths complex

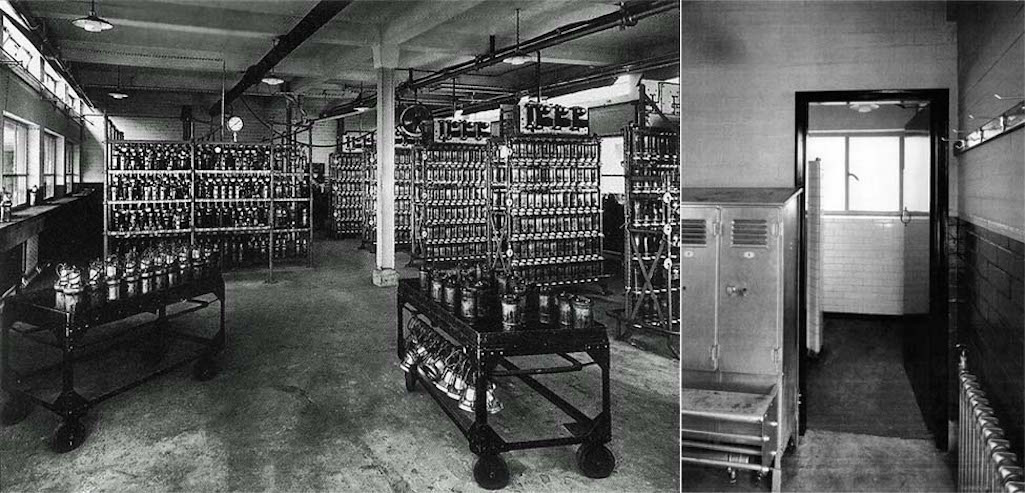

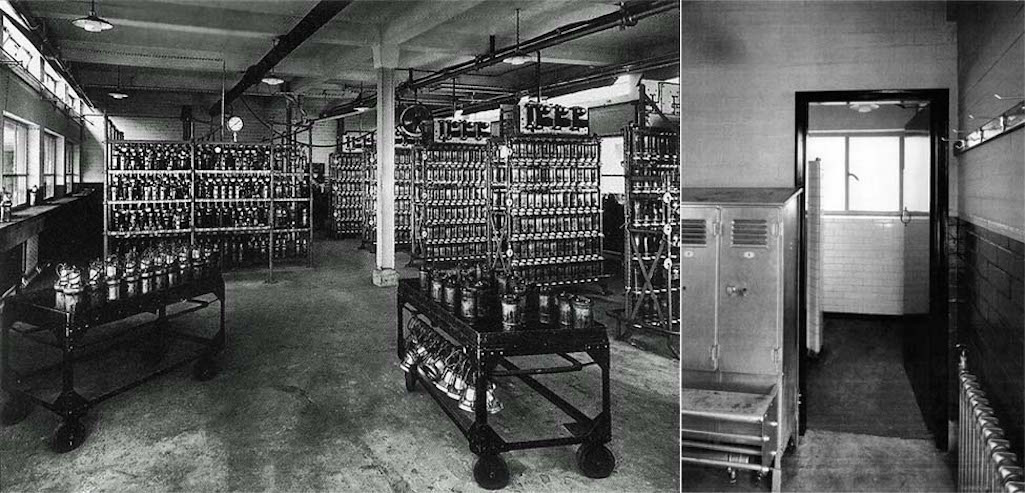

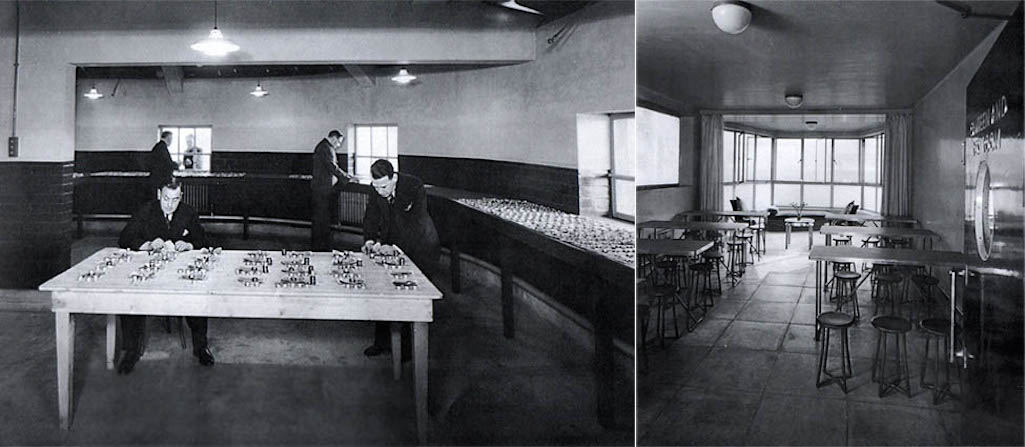

Left: Clock Face Colliery lamp room within the new complex; Right: Interior of the baths (showers) section

Left: Clock Face Colliery lamp room; Right: Interior of the baths section

The Clock Face Colliery lamp room

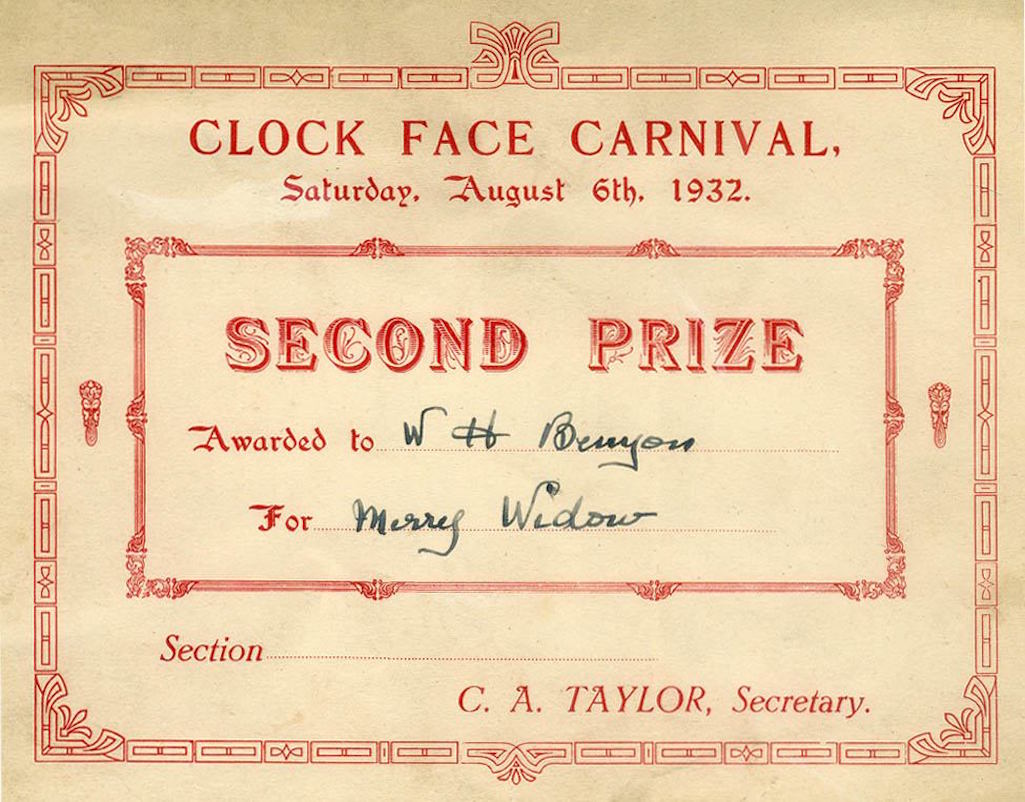

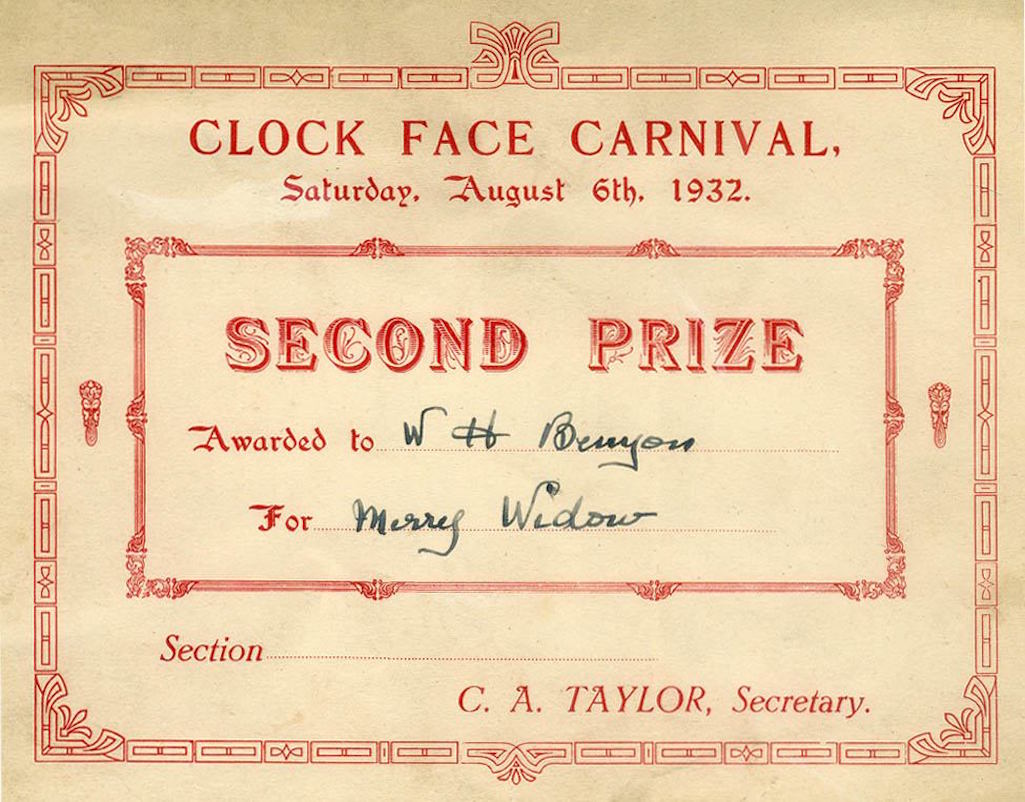

Mr. Benyon was awarded 2nd prize for his performance of what presumably was the music from the Merry Widow

Mr. Benyon was awarded second prize at the colliery carnival of 1932

Clock Face Colliery carnival 1932

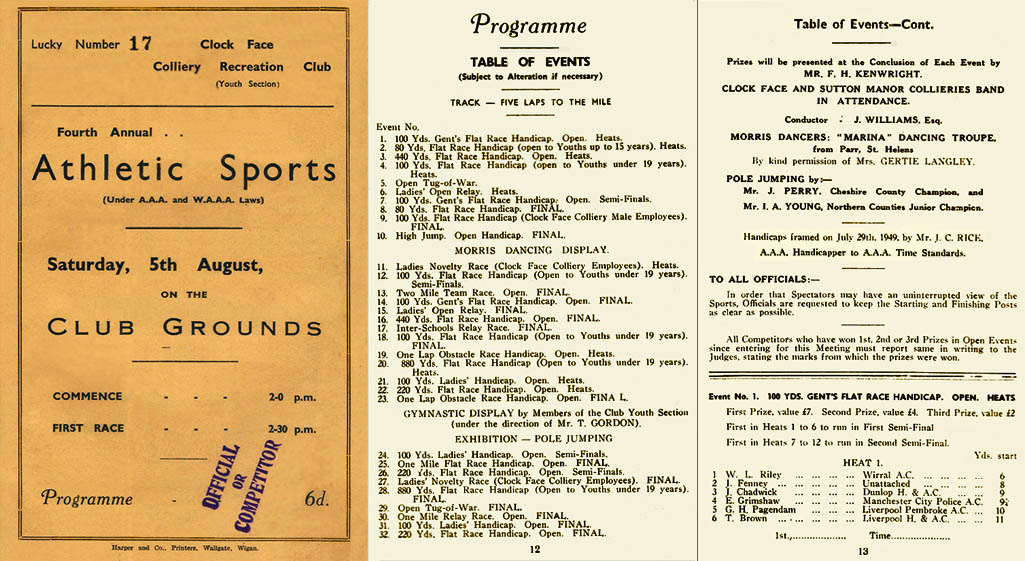

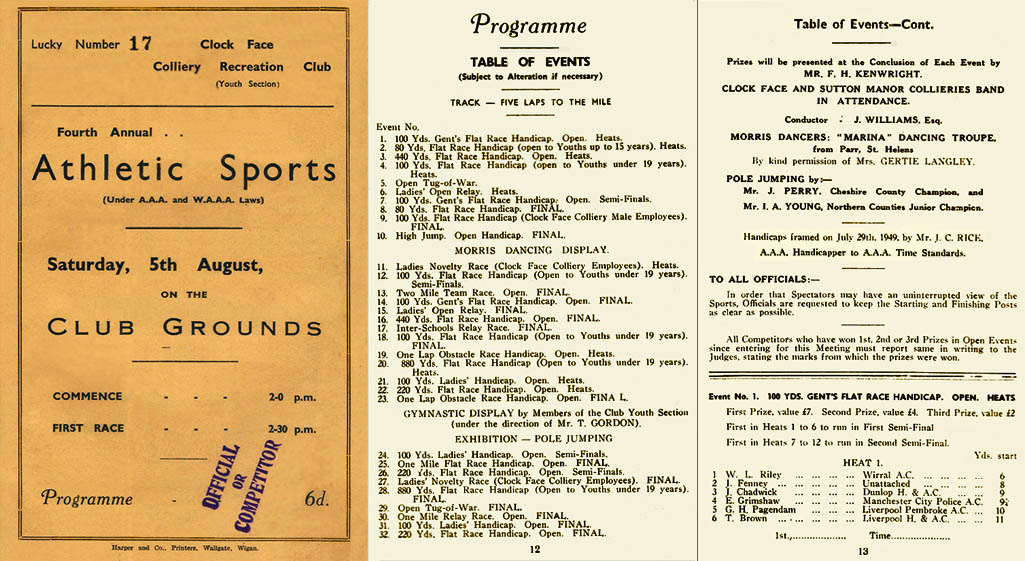

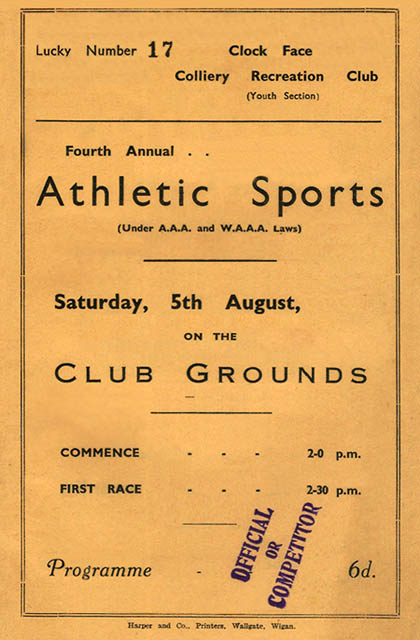

Programme for the Clock Face Colliery Recreation Club Athletic Sports 1950

Programme for the Clock Face Athletic Sports of 1950

Clock Face Sports 1950 Programme

Groups of miners also played accordions on summer evenings on waste ground during the 1920s, attracting good audiences. Another well-remembered conductor of the colliery band was Richard Fairhurst. Not all members were mineworkers, as cornet player Fred Fairhurst worked on Byron's farm. Edward Taylor was secretary of Clock Face Colliery Band in 1939, which was then led by John L. Williams. Isaac Hough of Gorsey Lane passed away in June of that year and in the St.Helens Reporter’s obituary, he was credited as a pioneer of the band, in which he played euphonium for about 20 years.

A picture of the popular Clock Face Colliery Band - Contributed by George Houghton

A picture of the popular Clock Face Colliery Prize Band

The Clock Face Colliery Prize Band

Clock Face Colliery Football Club 1949 - Ernest Patterson front row, 4th from left - can you name any others?

Clock Face Colliery Football Club pictured in 1949

Clock Face Colliery F. C. in 1949

On May 13th 1941 53-year-old John Leyland from Orville Street in Sutton died from the injuries he’d received at the colliery on April 9th. On September 16th of that year former Clock Face Colliery miner Joseph Lingham of 291 Sutton Road died at the age of 57. Lingham had been badly injured in the mine sixteen years earlier and had never worked since. Then on August 6th 1943 George Simpkin of Chancery Lane in Parr was killed by a fall of roof while packing the coal face.

On September 2nd 1943 George Smart from Lever Street in Clock Face was killed by a fall of stone. Fireman Ronald Pearson told Smart's inquest that he thought the 40-year-old coal-cutter had died instantly when a 3 ft. stone hit him on the head and a second dropped on his body. However the coroner was critical of the fact that Smart hadn't been wearing his helmet. Charles Bolton said: "If men would wear their helmets many lives would be saved. The helmets may be a nuisance, but they save men from death or from incapacitation."

During the 19th century mineworkers were occasionally taken to court for failing to turn up for work. This rarely happened in later years, apart from in wartime when coal had a greater national importance. So on October 22nd 1943 George Lea appeared in court on three charges of being absent from Clock Face Colliery without reasonable excuse and was fined £9 (about £300 in today’s money). On September 1st 1944 Samuel Pickavance of Manville Street was fined £6 for being absent from essential work without reasonable excuse. He told the court that he had been suffering from lumbago.

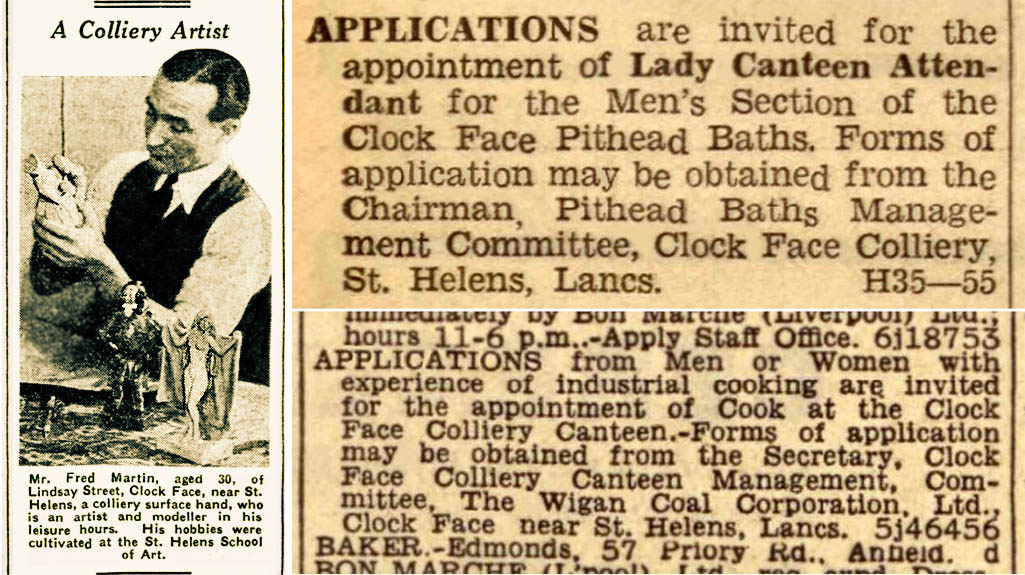

Left: Fred Martin in the Liverpool Echo on April 29th 1939; Right: Classified adverts from the Echo in 1943

Left: Liverpool Echo April 29th 1939; Right: Adverts in the Echo in 1943

Liverpool Echo of April 29th 1939

At the end of March 1948 the men went on strike for a week, through a dispute over pay. Some men had been moved from a 3 feet 9 inches seam to a very low one measuring just 2 feet four inches in order to improve the quality of coal. Output had subsequently fallen and the miners claimed they were losing at least 10 shillings a day and having to work much harder. The dispute was settled when new pay rates were agreed, although much output was lost.

In 1949 a mechanical gear to load coal trucks into the pit cages was installed at the colliery. However the banksmen who operated the system found there were difficulties with tubs sometimes sticking to one another. Consequently they had to be manually separated, which led to Francis Topping losing his life. In November of that year the 51-year-old from Hall Street in Clock Face stepped forward to free two stuck tubs. However he was crushed between a truck and an upright and received fatal injuries. On June 7th 1951 Francis’s wife Mary was awarded £1,750 damages against the National Coal Board.

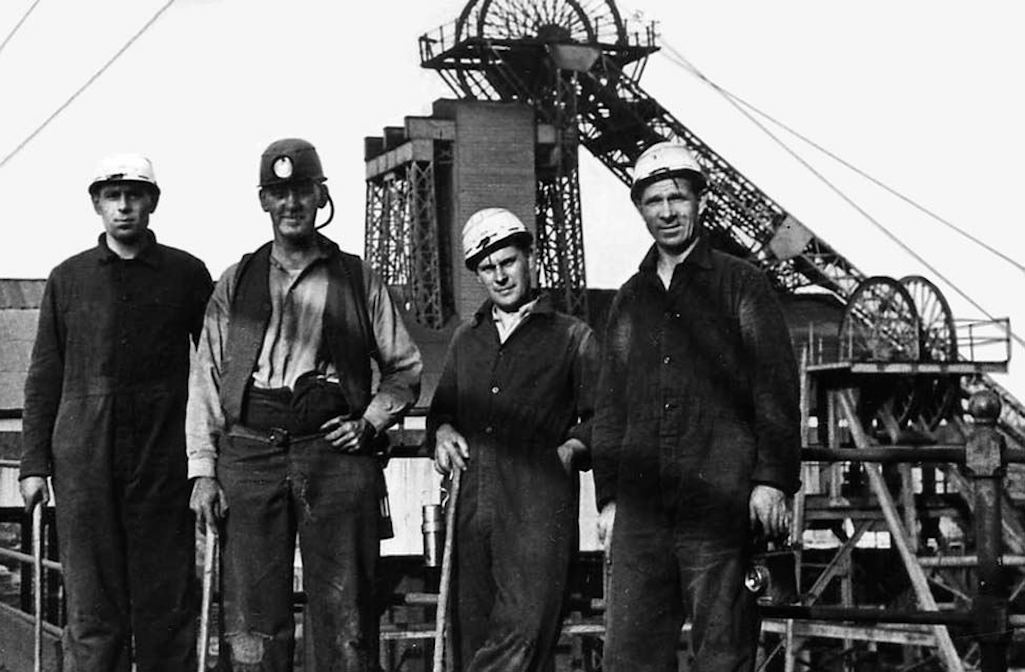

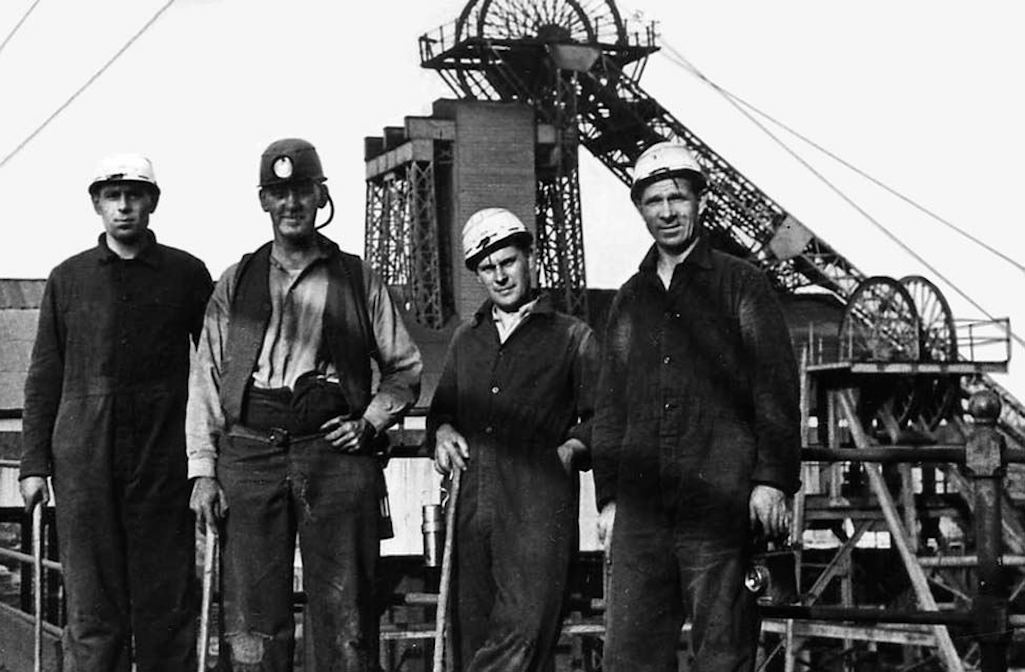

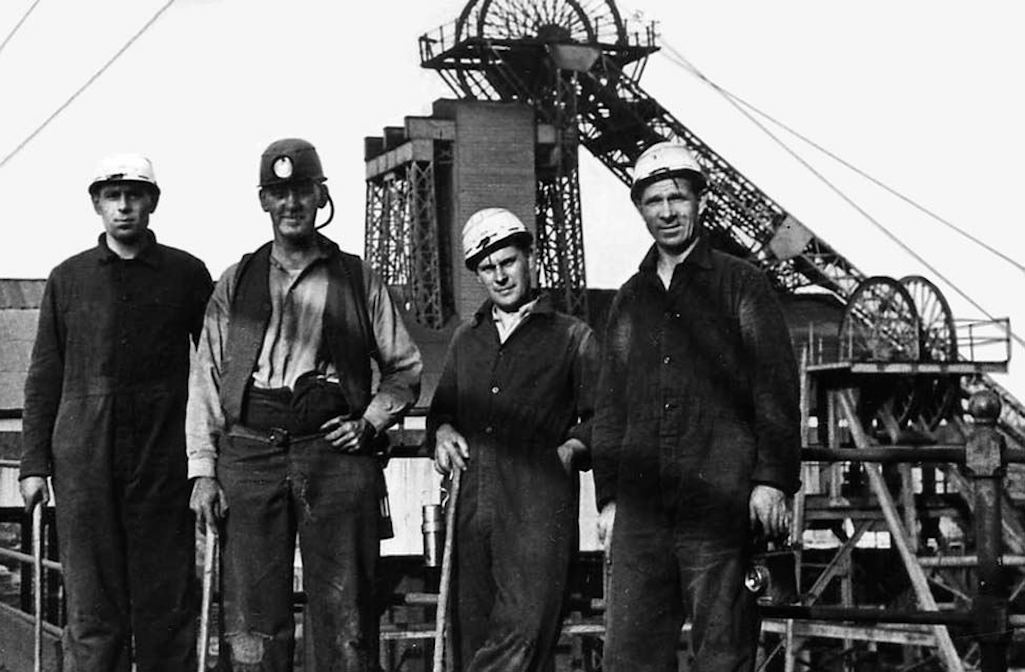

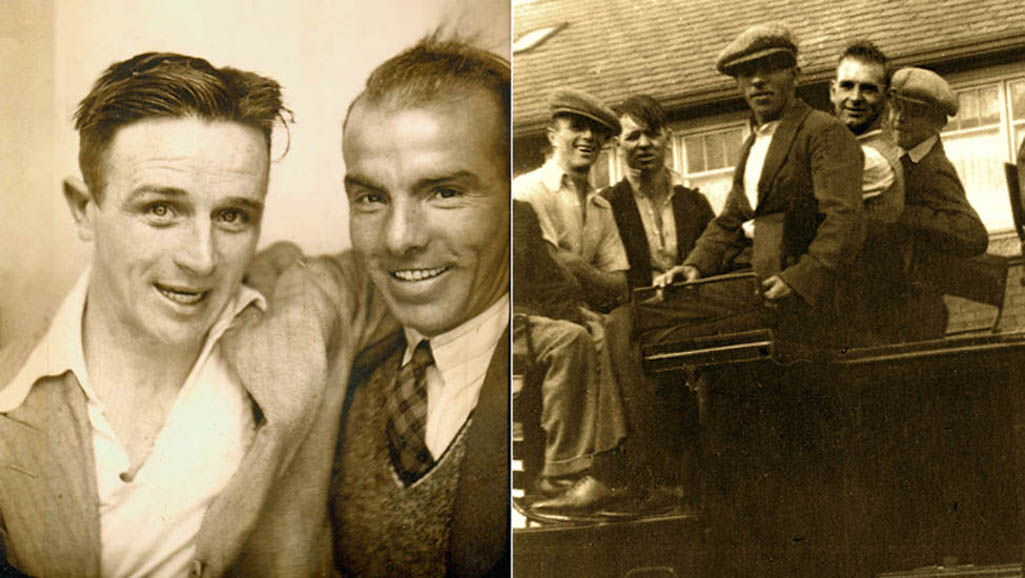

Horace Pugh is 2nd from right standing next to brother-in-law Frank Spakauskas (right) - John Williams is 2nd left

Horace Pugh is 2nd from right next to brother-in-law Frank Spakauskas

Horace Pugh is second from right

One little known fact is that Clock Face Colliery played a role in the Berlin Airlift of 1948. After Stalin's blockade was imposed on West Berlin, US Army trucks lined up in Gorsey Lane to be filled with Clock Face coal. This was then flown onto Germany from Burtonwood Air Base. One problem was that the coal was not stored in sacks but loose in the cargo holds of planes. It tended to shift in flight which caused some difficulties for the pilots.

After nationalisation of the coal mines, a Labour government in power and a national pay agreement, it was hoped that there would be industrial harmony in the mines. However for two years the issue of concessional coal led to considerable disruption in the Lancashire coalfield and in May 1949, 50,000 miners in 65 pits went on strike. When the industry was in private hands, the owners had different arrangements on a town and pit basis. During 1948 five million tons of coal at free or reduced prices had been distributed nationally to mine workers and managers.

However St Helens was the only town in Lancashire that granted concessionary coal, with Clock Face Colliery having the most generous scheme. All miners who were householders or had dependants, received a ton of coal every 28 days at 5 shillings a ton, which was much less than the retail price. The long-standing dispute was finally settled in April 1950 when it was agreed that all miners would receive 4 tons 8 cwt at 21 shillings below retail price. This would cost the National Coal Board (NCB) £136,000 per year and Clock Face miners had to accept a far-less generous concessionary scheme than the one they’d been used to.

In October 1950 Joseph Forster died at the Griffin Inn in Bold Heath at the age of eighty. For 38 years he had been an engineer at the colliery and a trustee of the Clock Face Colliery Club, as well as a school manager of the Clock Face Colliery school and that at Bold Heath. Forster had also been a magistrate on the Widnes Bench, a parish councillor for 16 years and a district councillor for 28 years.

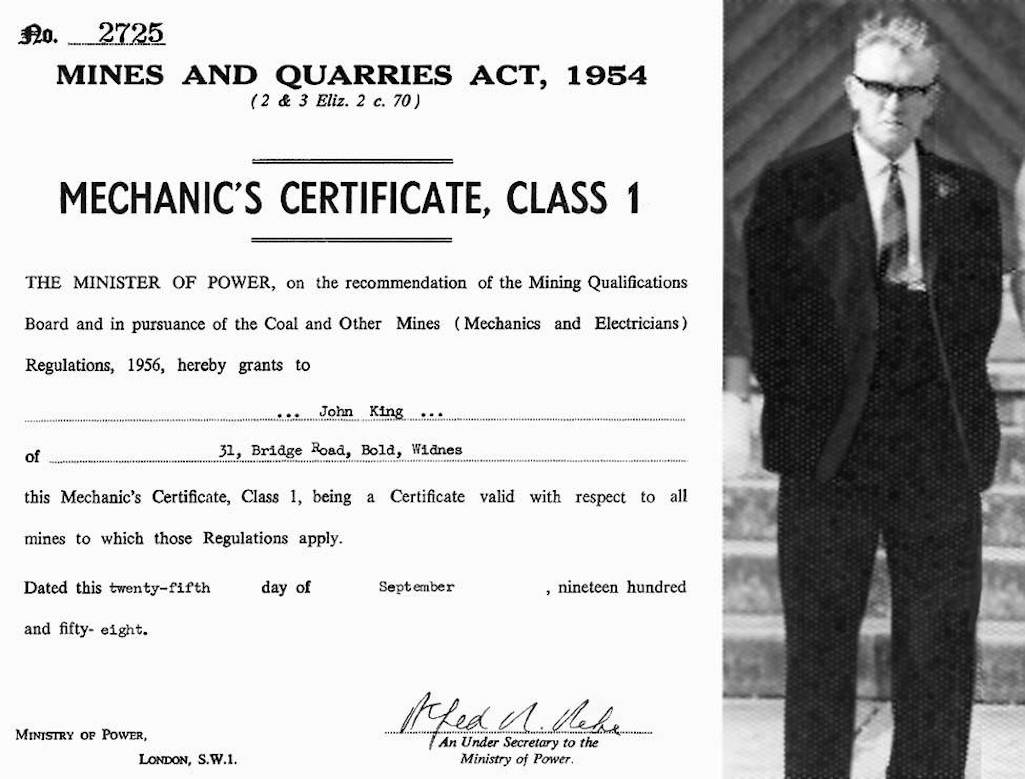

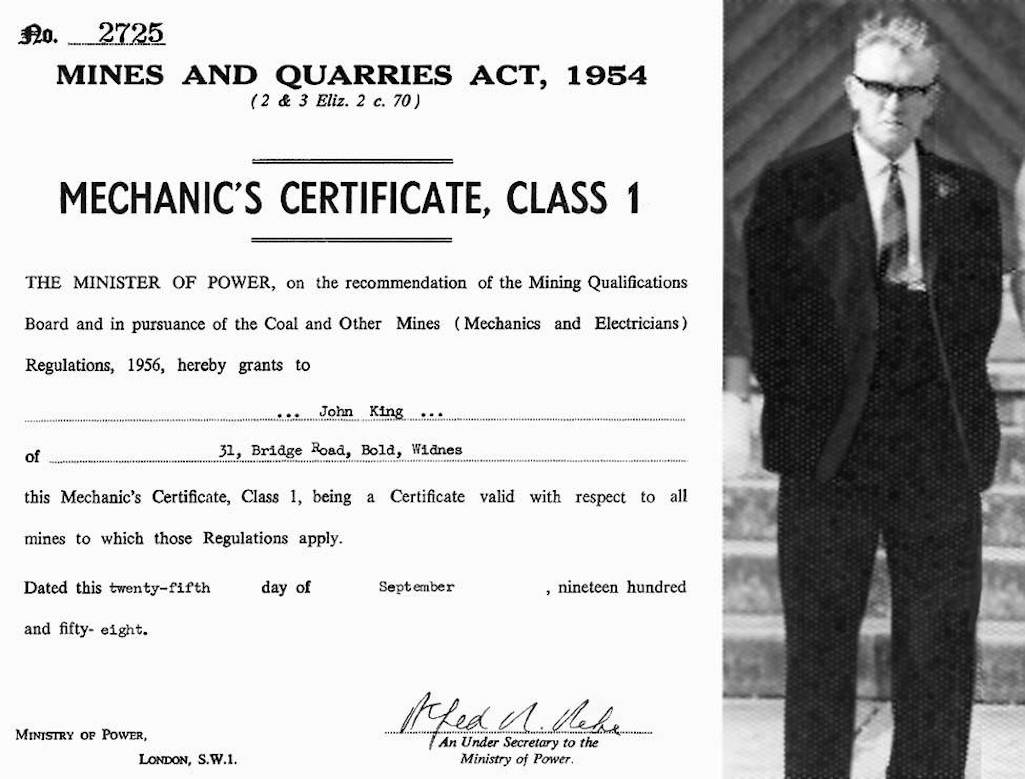

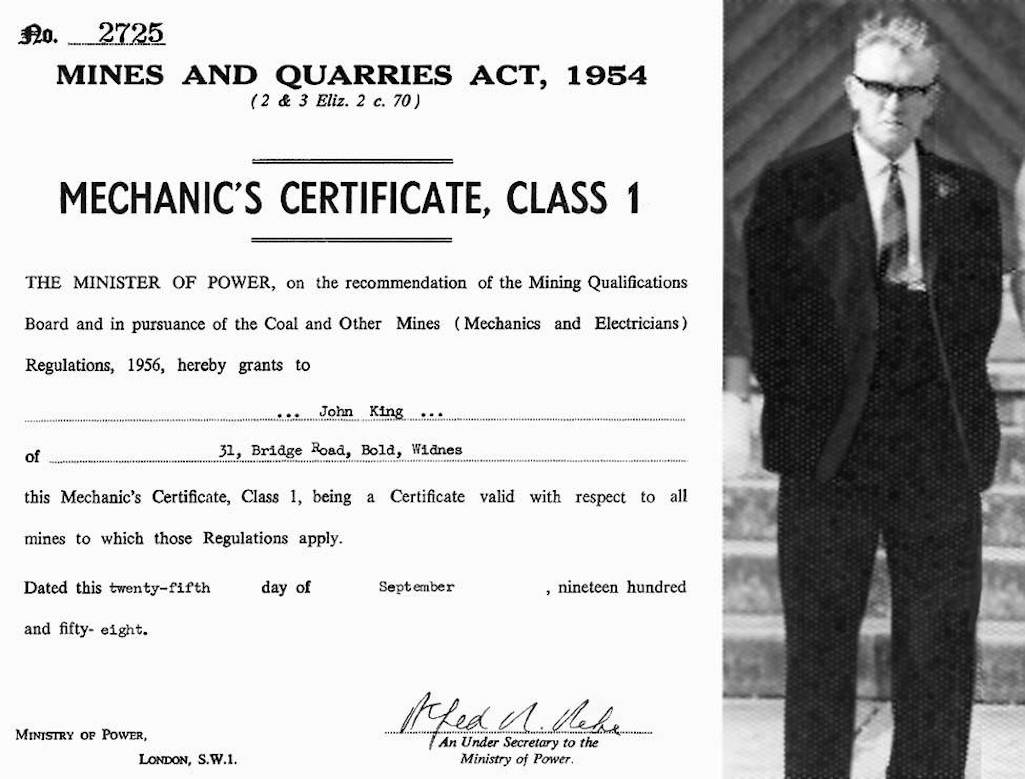

John King who was in charge of the winding house at Clock Face Colliery - Contributed by John James

John King who was in charge of the winding house at Clock Face Colliery

John King was a winder at Clock Face

During the 1940s and ‘50s John King held that important position at Clock Face Colliery. He entered the mining industry in 1918 at the age of 13 when he got a job at Pemberton Colliery, assisted by a reference from John Woods, Vicar of Highfield. After transferring first to Cronton Colliery, John King relocated to Clock Face where he lived at 31 Bridge Road. In 1958 as pit winder he received his Mechanic’s Certificate under the Mines and Quarries Act, shortly before moving to Sutton Manor Colliery.

On May 22nd 1955 Clock Face Colliery played its part in a special celebration at Blackpool when 600 veteran mineworkers from Lancashire paraded through the town. Every man had retired during the previous year after serving at least 50 years in the industry. Area NUM secretary Edwin Hall explained to the press that the outing was organised by the Coal Industrial Social Welfare Organisation – a joint NCB and NUM body – to thank the men for their service. The Clock Face Colliery band was one of several that provided music in the procession and some of the marchers were formerly of the colliery. The ex-miners arrived by special train and received a lunch at a civic reception hosted by the Mayor of Blackpool and 10 shillings each for their teas.

In October 1956 the NCB gave notice to 24 workers at Clock Face that, as a result of their attitude, they were going to be sacked. It was alleged that the men were not pulling their weight after a dispute at the pit. There were suggestions that they would be offered work at other pits but on the 19th of October the notices were withdrawn. The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) said this was as a result of them informing the coal board of a number of mechanical breakdowns, which had reduced the flow of coal.

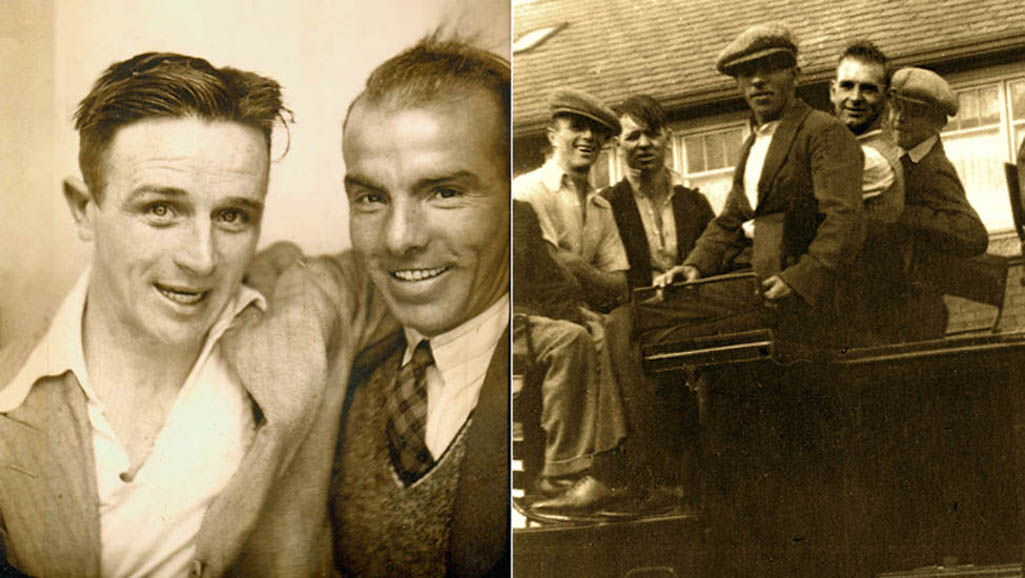

Left: Eddie Lea, Allan Smith & Bill Carr; Right: Bob Cornish technical assistant to Cec Ryan, area mechanisation engineer

Pit Prop portrait gallery: Eddie Lea, Allan Smith, Bill Carr and Bob Cornish

Eddie Lea, Allan Smith and Bill Carr

In early ‘pillar and stall’ mining the usual method of extracting coal was by an individual miner and his drawer, with the latter collecting and removing the coal. These worked in a chamber of coal called a stall, which had its roof generally supported by coal pillars and wooden props. The miner would, crouching down, hand pick the coalface a couple of feet from the floor along its free length to the depth of his pick. Holes would be drilled along this length above the undercut, and explosive charges put into them. Firing the charges would result in the vertical collapse of coal over the length, with the drawer then filling the tubs and pushing them out to a haulage collection point, usually by pony. Although this primitive method created some dust, it wasn't a large amount in comparison to later methods.

Left: An example of pillar and stall mining; Right: How the terrible disease pneumoconosis blackened lungs

An example of pillar & stall mining and how pneumoconosis blackened lungs

Left: Pillar and stall mining; Right: How pneumoconosis blackened lungs

In addition the significantly improved ventilation carried the released dust out of the face area and along the many tunnels towards the uptake shaft, with various amounts settling on beams, road floors, equipment, conveyors, etc. Anybody working underground was subject to breathing in the suspended dust that was continually passing through the air.

This became the source of the terrible lung disease ‘pneumoconosis’, or ‘black lung disease’, as it was also known. Once coal dust entered the lungs it was impossible for it to come out and it progressively accumulated to a point were breathing became severely restricted. The waiting room at first Dr John Unsworth's, and then Dr Rory O'Donnell's surgery in Leach Lane in Sutton during the 1940s, ’50s and ‘60s, always had a number of the unfortunate mine workers who had this condition.

Their sunken eyes, grey drawn face, with the most rasping of coughs and wheezing of breaths, was so sad to experience; especially as they knew that nothing medically could be done to reverse their terrible condition. Horace Longworth worked down Clock Face Colliery for 38 years and his daughter Margaret Braithwaite explains in her Memories of Sutton article how after her father’s death, the pathologist had described his lungs as being like “black cement”.

The second equally major problem resulting from these changes was that of coal dust explosions following a gas (usually methane) explosion. After mechanisation gas release from within the coal seam was much more frequent than in the old method of mining. There are a number of ways the gas could be ignited, but the resulting explosion would create a significant explosive force, which passed down the coal face and then into the tunnel system, which connected to the shaft.

During this passage the coal dust that was lying along its length would be lifted into the air. If it is in its combustible form, as pure coal dust, it would immediately explode and ignite, continuously fuelling itself as the flame travelled towards the shaft. Over the years there have been some terrible consequences of dust explosions, with the one at the Hulton Colliery in Bolton on the 21st December 1910, in which 344 men and boys were killed, being a tragic example. Some of the victims died almost a mile from the scene of the coal face gas explosion through the effects of carbon monoxide, caused by the coal dust fire consuming all the oxygen.

The elimination of coal dust in mining was, of course, impossible, so finally after WW1 serious examination of the best methods of minimising these dangers was started. This resulted in the use of stone dust, usually limestone, in all mines to neutralise the explosive characteristics of coal dust. The principle was based on reducing as much as possible the available coal dust’s combustion levels, by mixing the two dusts to a percentage that would not ignite.

The process was expensive to maintain because hundreds of tons of stone dust were required on a monthly basis, plus the cost of dedicated underground people, who you could always spot at the end of a shift with white dust on their clothing and boots. It was carried out under a strictly controlled programme of area dust sampling throughout the mine. These samples were tested by the colliery chemist, who would subsequently report on what was required in the sample areas.

The bags of stone dust, similar in size and weight to a bag of cement, were opened and hand-applied in the various roadway tunnels by being thrown into the ventilation stream of air. This would allow it to mix with the airborne coal dust in that area, eventually settling on nearby surfaces of road and equipment, with the team then moving on to the next sample area. The basic theory was that any subsequent gas explosion air movement would only lift the top amount of the settled mixture back into the air, and if mixed to the correct ratio it would not ignite.

In later years stone dust barriers were also introduced to hang from the roadway roof along its route, which if impacted by a sudden rush of air from an explosion, would release a large quantity of stone dust into the air targeted to put out the following flame. The position of the dust suppression officer at each colliery was made to specifically make one person responsible for coordinating all the activities involved, and he would report to the undermanager, but worked very closely with the overmen, deputies, and mechanisation team. Eddie Lea as dust suppression officer at Clock Face would also be involved in trying to reduce the source and amount of dust that was generated on the coal face, which would involve the cutter pick design, with water spray application if practical.

He would travel all over the workings of the mine, checking on rotating equipment and applying grease to greasing points, including conveyor drive rollers, endless haulage pulleys etc. Without this work, bearings could run hot with friction (with dust a big factor), and any unscheduled stoppage would have a major impact throughout the production delivery system.

Bob Connolly's role as part of the haulage team is another important one, dedicated to getting the supplies of equipment to the various underground areas as soon as possible after their arrival at the shaft bottom. The supplies would include timber/ hydraulic props, steel tunnel arches, timber packing, pipework, stone dust and many, many more items. These would travel in tubs as far as possible, before being manhandled to their desired location and made safe. It can be appreciated that any failure to have such items in place when required, could impact upon production. The aim of Pit Prop was to publicise these key people, and photographer Frank Grimshaw really enjoyed playing his part in bringing them to the magazine’s many readers.

There are many who still recall the sight of black-faced miners walking through Clock Face village during the 1950s, including Ernie Bate:

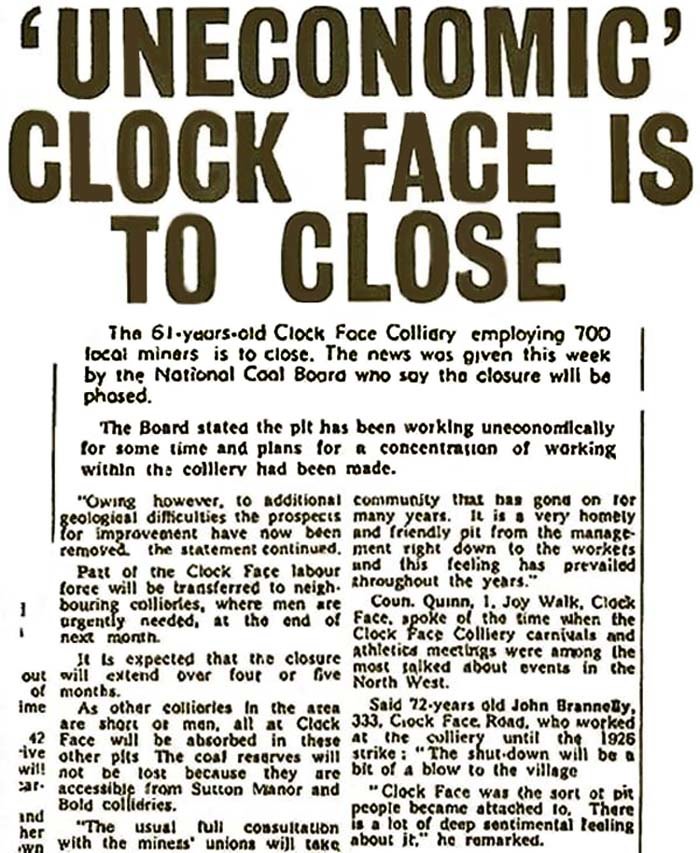

Clock Face Colliery closure as announced in the St Helens Reporter of 23/10/1965

The closure as announced in the St Helens Reporter of 23/10/1965

St Helens Reporter of 23/10/1965

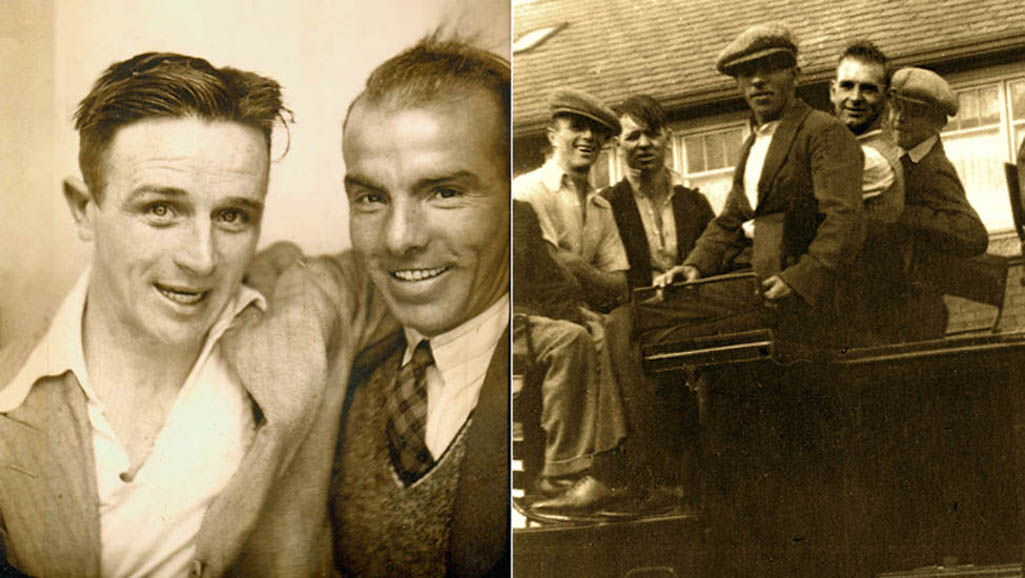

Clock Face Colliery lampman Johnny Quinn with best friend and fellow pitman David Mercer

Clock Face Colliery lampman Johnny Quinn with fellow pitman David Mercer

Lampman Johnny Quinn & David Mercer

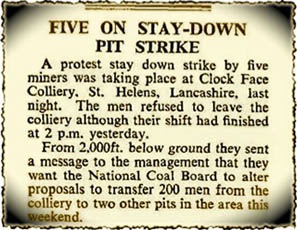

They were protesting at the way the pit would be phased out and staff transferred. Although the NCB had promised that all miners would be transferred to other collieries, the NUM secretary at Clock Face, Paddy Meeghan, claimed that union officials in neighbouring pits had told him that there wouldn't be enough work to go round. Meeghan said the strike was intended to call the coal board's bluff. If there were alternative jobs for all 700 men, why couldn't they all be transferred at once?

In the Guardian newspaper of November 26th 1965, a large photograph of miners’ wives Elsie Elliot and Agnes McDermott, plus the latter’s 14-year-old daughter Pat appeared. The trio were shown arriving at the colliery with food and flasks of tea for the miners who as the paper put it, were staging a 'stay in' strike 2,000 feet underground. The nine men - who had ensconced themselves in an office in a brick hut - included the president, treasurer and two committee members of the union branch. Their protest, however, only lasted 48 hours.

After the colliery closed, a pump was installed to daily deliver tens of thousands of gallons of near pure water from underground to Sutton Manor Colliery and into the public water system. The site was reclaimed by St Helens Council as a community woodland and public open space in the late 1990s and is now known as Clock Face Country Park and enjoyed by many. Other than the hidden-away capped shafts, the old baths and lamp storage complex in Gorsey Lane is currently all that's left of the historic colliery. However on February 5th 2015, St.Helens Council granted planning permission for the building of 19 homes on the site.

Capped shaft number 1 at the former site of Clock Face Colliery pictured in 2009 - contributed by Neil Selfridge

Capped shaft number 1 at the former site of Clock Face Colliery

Capped shaft number 1 in 2009