An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 20 (of 95 parts) - The History of Industry in Sutton Part 1

d) Chemical & Alkali Works (inc. Leathers, Hays & British Sidac) | e) Brook’s Blue Works

Industry Part 2 (Iron Works, Engineering, Locos), Part 3 (Sutton Mill), Part 4 (Crone & Taylor)

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me Research Sources

c) Rolling Mill & Copper Works | d) Chemical & Alkali Works

e) Brook’s Blue Works | Also See: Industry Parts 2, 3 & 4

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Old Sutton in St Helens

Glassmaking in Sutton

Rolling Mill & Copper Works

Chemical & Alkali Works

Brook’s Blue Works

a) Clay, Pottery and Brickworks in Sutton

Sutton clay provided employment for countless workers over hundreds of years, with pottery-making traced as far back as the 12th century. The Old Teapot Brick Works, Ravenhead Brick Co., the Sutton Drain, Tile & Garden Pot Works and Roughdales, are just some of the more recent pottery and brick-making employers in the Sutton district that are now long-gone.In the Liverpool Mercury of June 29th 1860, a house, cottage and three acres of land in Chester Lane were advertised for auction. It was claimed that the land contained 'a bed of most valuable potters and firebrick clay, of great thickness'. Eight years later the Roughdales Fireclay Company Ltd. (later Roughdales Brick & Coal Co.) began their operations off Chester Lane. The company was registered in June 1868 with a capital of £20,000.

The branch line from the company's works to the main railway line at Lea Green - which had a length of 587 yards - was formally opened at 2pm on July 14th 1870 at Lea Green Station. The chairman of the company Isaac Dixon and its directors, officers and shareholders then commuted on their new line to their works, where speeches and celebrations took place. The latter included dancing to a local band and a footrace.

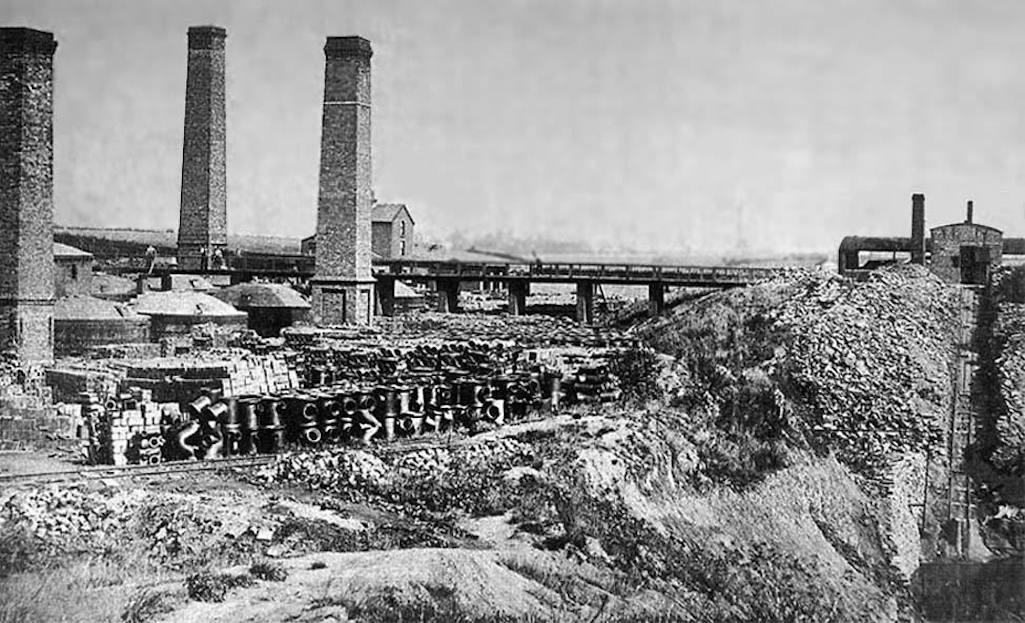

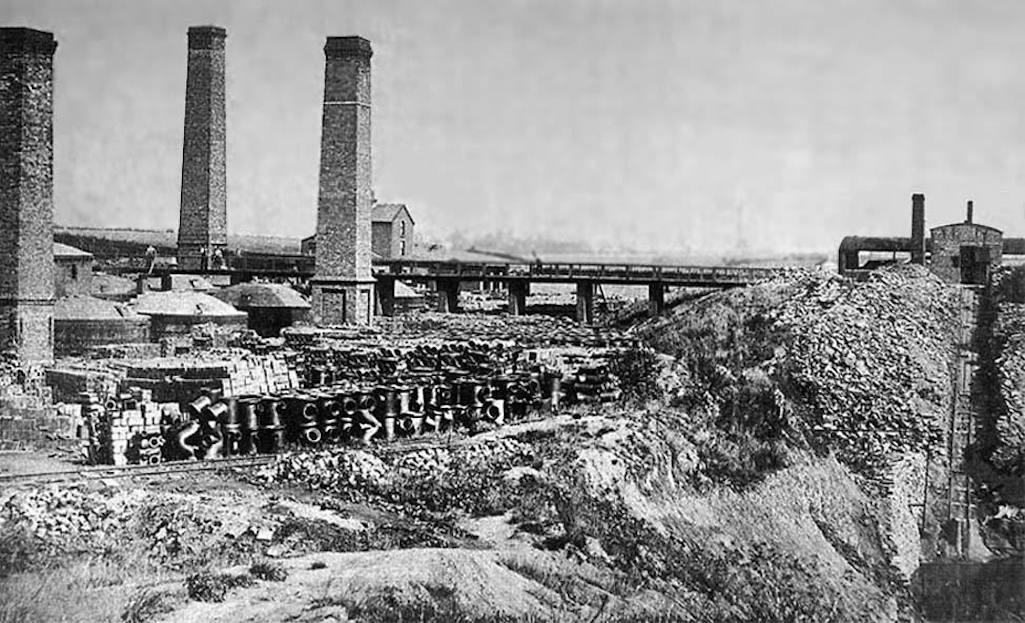

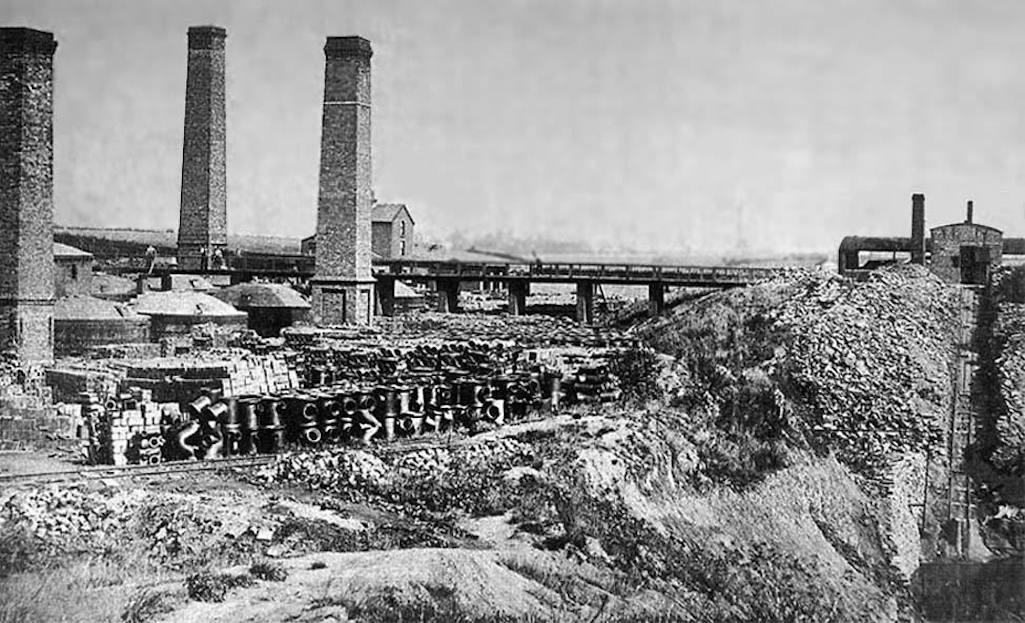

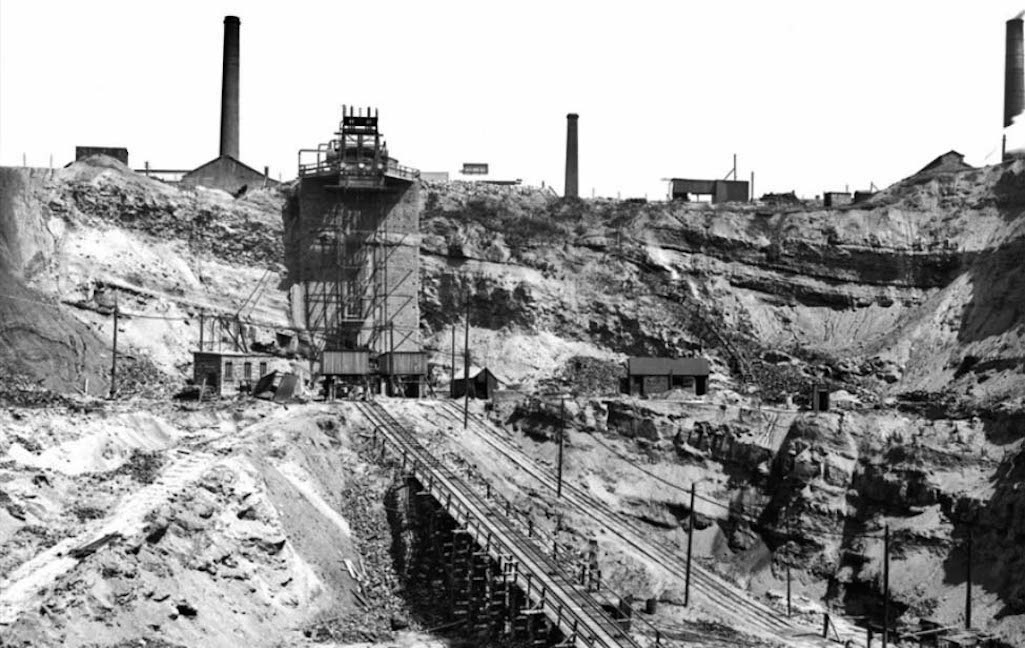

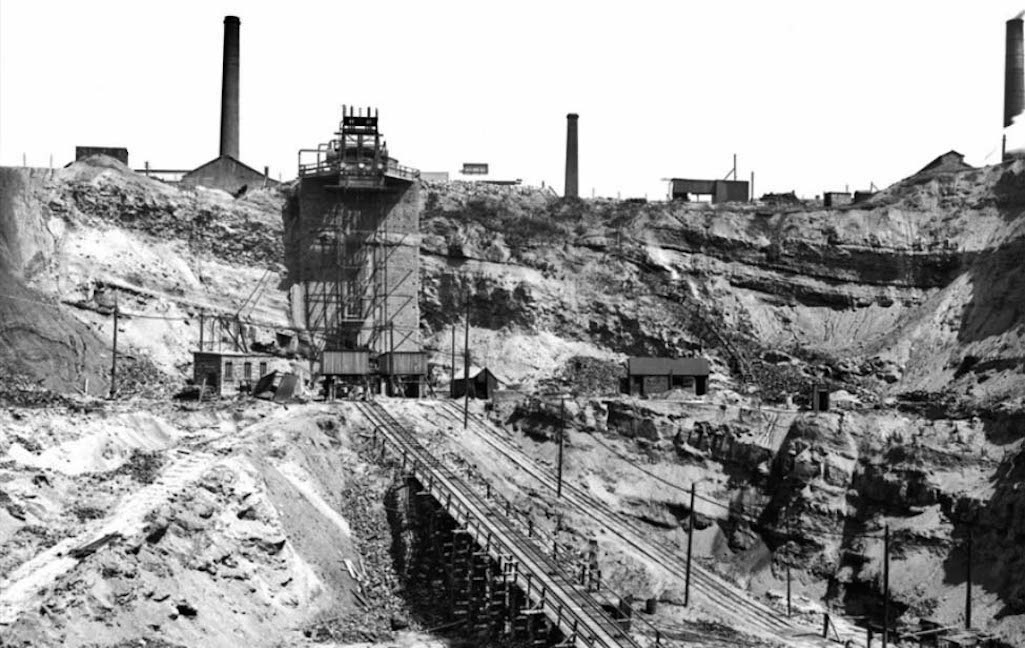

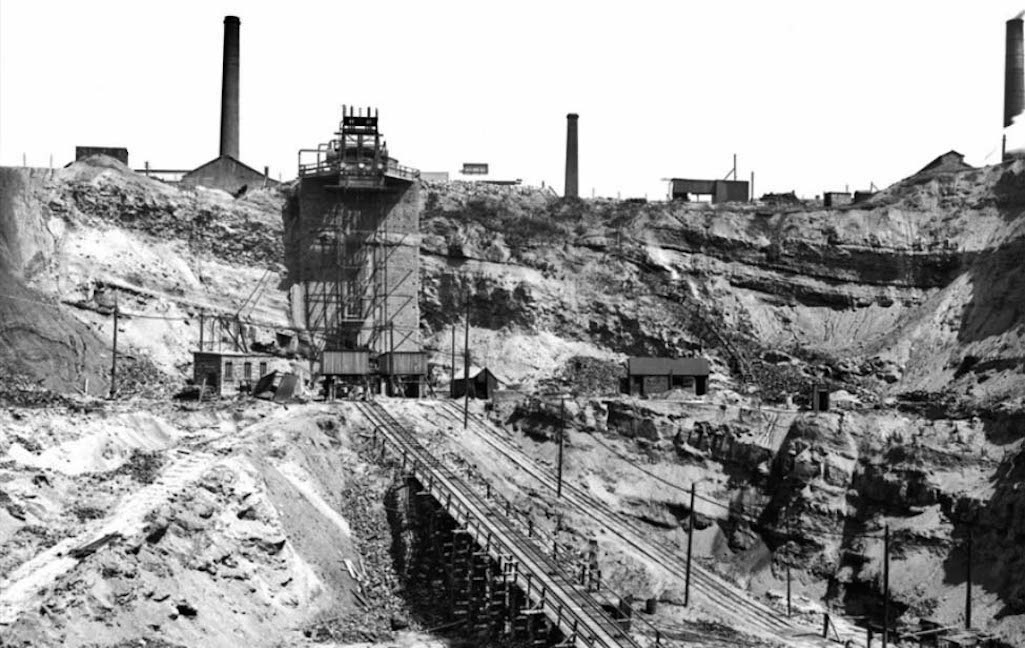

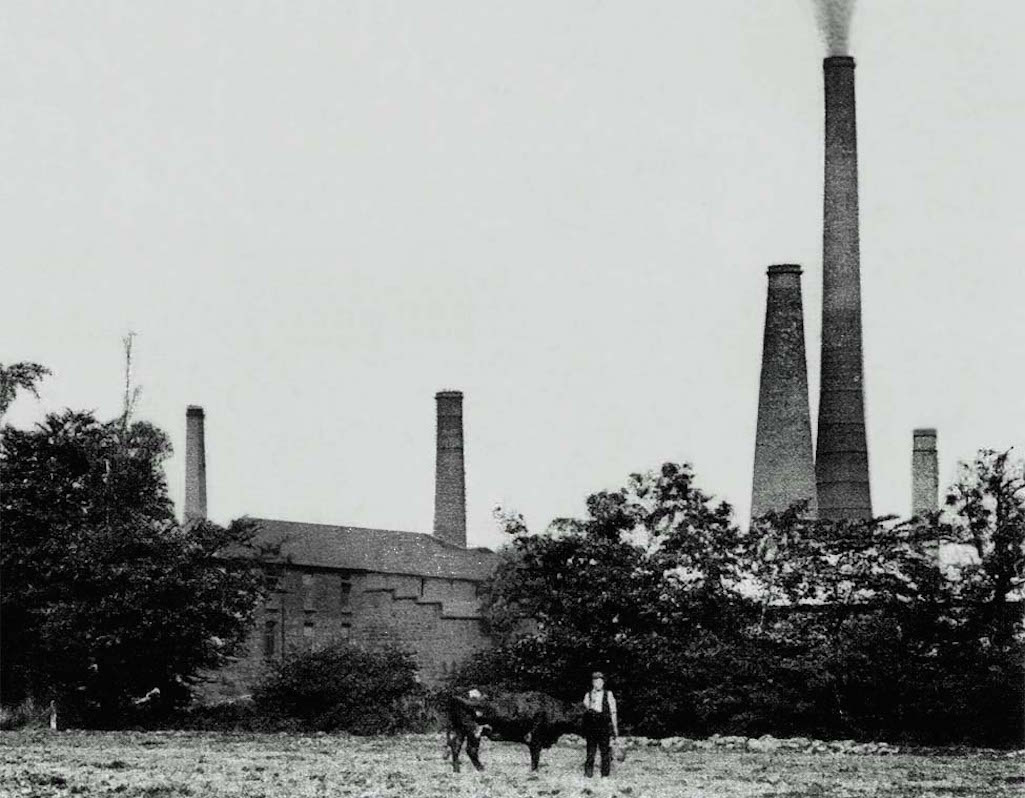

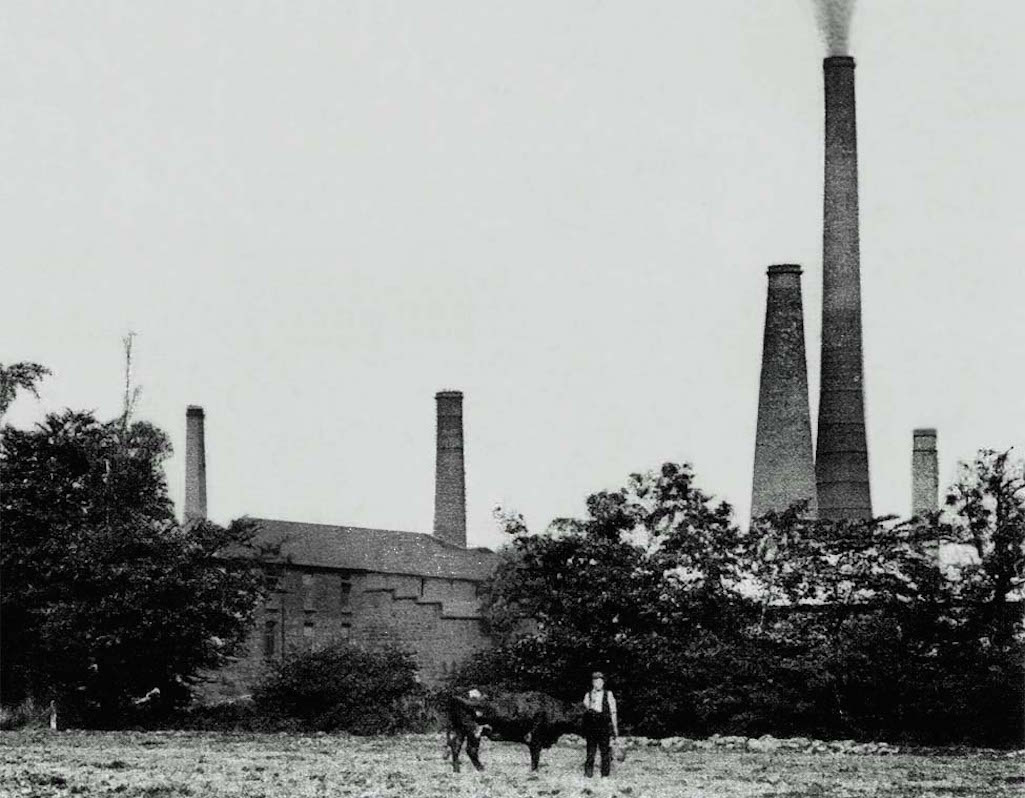

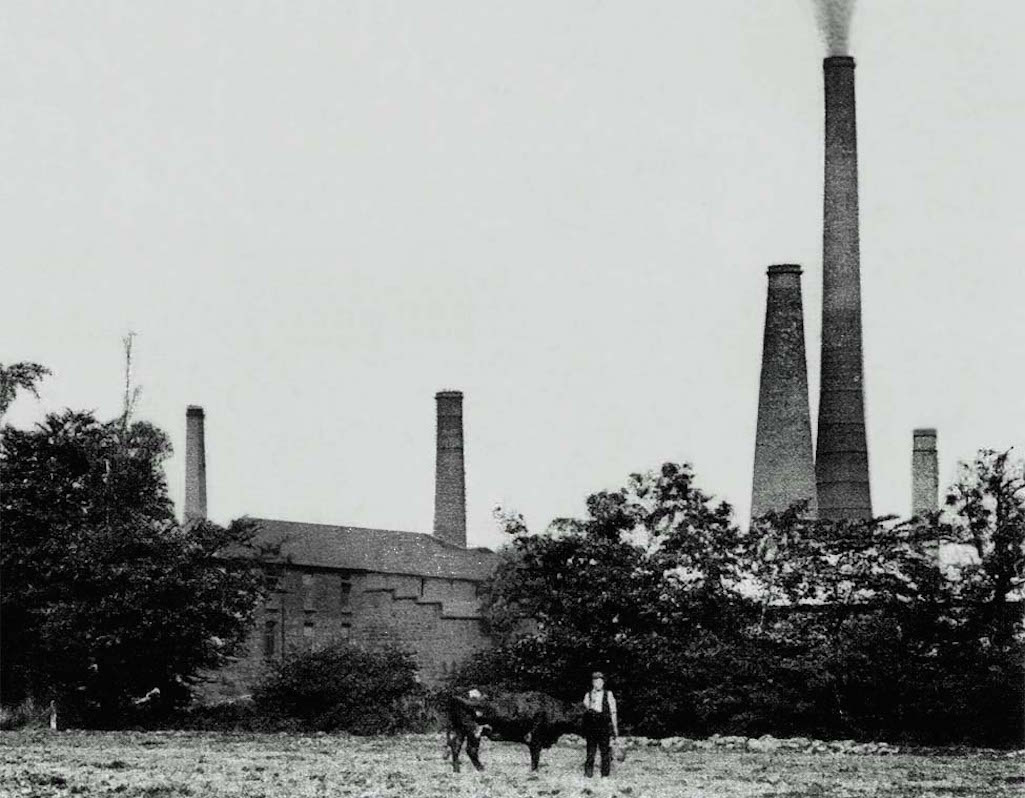

The Roughdales Fire Clay Company works in 1890 which were located in Chester Lane, Sutton

Roughdales Fire Clay Company works in 1890 in Chester Lane, Sutton

Roughdales Fire Clay Co. in 1890

In another Liverpool Mercury advertisement of December 15th 1886, Roughdales described their business as 'Manufacturers and Exporters of BLUE VITRIFIED FACING BRICKS, brindled and hard-burnt Building Bricks, Terra Metallic Pavements (plain and chequered), Adamant Pavings for Stables, superior glazed Sanitary Pipes and Gullies, Chimney Pots of all kinds. Chemical Pipes specially prepared for withstanding acids and gases.' The Roughdales Brass Band was renowned throughout the region and played at countless celebratory events such as walking days, as well as some funeral processions.

Early in the 20th century, Roughdales was acquired by the Sutton Heath and Lea Green Collieries Co., who also owned a brickworks in Sutton Heath that had been erected in 1912. In 1920 they became a limited company and in their prospectus claimed a pre-war output of 14.7 million bricks per year. They stated that their intention was to develop their two Sutton works and output 25 million bricks per annum. On July 11th 1939 it was reported that 250 men and ‘girls’ employed at the two brickworks had come out on strike over a pay dispute concerning female employees.

Ibstock quarry in 1990 - note bricks on left and Sutton Manor Colliery in the distance - Contributed by Jim Lamb

Ibstock quarry in 1990 - note bricks and Sutton Manor Colliery in the distance

Ibstock quarry pictured in 1990

In January 1962 Roughdales acquired the Greengate Brickworks from Pilkingtons and in June 1963 announced they were buying out the Sutton Oak Brick Company. Chairman James Spencely said Roughdales then had 250 employees with Sutton Oak and its subsidiary companies employing 70 people.

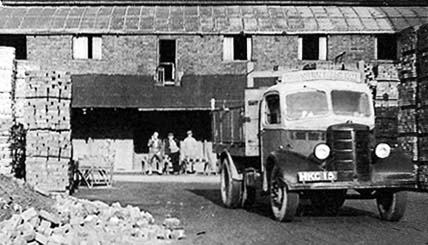

On February 21st 1969 the St Helens Reporter described how a new ‘tunnel kiln’ would be made operational at the Chester Lane plant during the late summer. This would allow for the production of large quantities of bricks within three days and was part of a £½ million modernisation programme. The company’s managing director, J. S. Robinson, said that not so many years ago it would have taken three weeks to manufacture a similar quantity. Mr Robinson added that Roughdales two works at Chester Lane and Elton Head (which already had a tunnel kiln) would now be capable of producing 40 million bricks a year between them.

Much of the new investment was about automating the brick making process, cutting out the backbreaking labour of the past. Already at Elton Head almost every phase of the brick’s production was automated “from when the clay is dragged from the ground to when the stacks of bricks are fed into the massive oven and then delivered.”

Once the bricks had left the kiln and cooled, they were made up into batches of 375, banded (bound with steel strips) and stacked. Instead of being loaded singly onto a truck, the whole batch is then loaded and delivered to the customer using a crane. Roughdale’s had a fleet of seven crane vehicles and were hoping to expand this to a dozen.

On June 13th 1969 the St Helens Reporter said a petition had been launched by local residents calling for two pits belonging to Roughdales to be fenced off. Over the years it was stated that the deep clay pits near Walkers Lane had taken the lives of several youngsters and had recently become more of a menace through the building of a housing estate. Children floundering in the 100 ft. deep pits have had to be pulled to safety by friends and worried parents were forming patrols to prevent children from entering the water. Roughdales responded by saying that work was already in hand for the building of a fence around the pits, as well as a gate for the access road.

Ibstock Brickworks Roughdales plant pictured February 2007, closed December 2008 and demolished June 2011

Ibstock Roughdales plant in 2007 and demolished in 2011

Ibstock’s Roughdales plant in 2007

During its last few years, the Ibstock works used methane gas from the adjacent landfills to power its ‘firing’ operations. The closure of the plant with 56 redundancies brought to a close a lengthy heritage of clay and brickworks in the district. The factory was flattened in June 2011 and the sign at the entrance is all that remains. In March 2014 a planning application was submitted to St. Helens Council to build 250 homes on the site.

Ravenhead Sanitary Pipe & Brick Company off Burtonhead Road - Contributed by Harry Hickson

Ravenhead Sanitary Pipe & Brick Company which was off Burtonhead Road

Ravenhead Sanitary Pipe & Brick Co.

A boiler explosion took place at the works on November 11th 1869 in which a number of workmen had miraculous escapes. The 25ft. long boiler was in a shed and the explosion brought down the outer wall and part of the roof. Several men were working in the shed at the time and one was buried under the debris and one or two others received minor injuries after being struck by flying bricks. Two huge pieces of the boiler – that were each at least a ton in weight – were projected to a distance of 30 yards and large sheets of iron were strewn over the field in which the shed was situated. The Prescot Reporter wrote: "It seems perfectly wonderful how the men escaped maiming or death in such a scene."

In May 1874 the partnership of Mr. Horn and Mr. Kelly was dissolved and David Horn appears to have taken over the business and in 1875 it was registered as the Ravenhead Sanitary Pipe and Brick Co. Ltd. Pipe manufacturing ceased around 1880 to concentrate on brick making. Their clay was sourced from opencast workings on the opposite side of Burtonhead Road, covering an area of 12 acres. In 1914 the company advertised for men to work in their clayhole offering wages of 6d. per hour 'for good steady men'. During this period James Heaton of Prescot Road was the managing director of the company. He was also chairman of the St Helens education authority and a magistrate.

A dreadful tragedy occurred at the brickworks on Christmas Eve 1931 when 6-years-old Annie Dawson of Essex Street fell into a well of boiling water. She was rescued by fitter Alfred Gleave but died two hours later in St.Helens Hospital. Gleave was badly scalded and was later rewarded by the Carnegie Hero Fund with a £15 award. In 1960 Roughdales took over the plant and closed it a few years later.

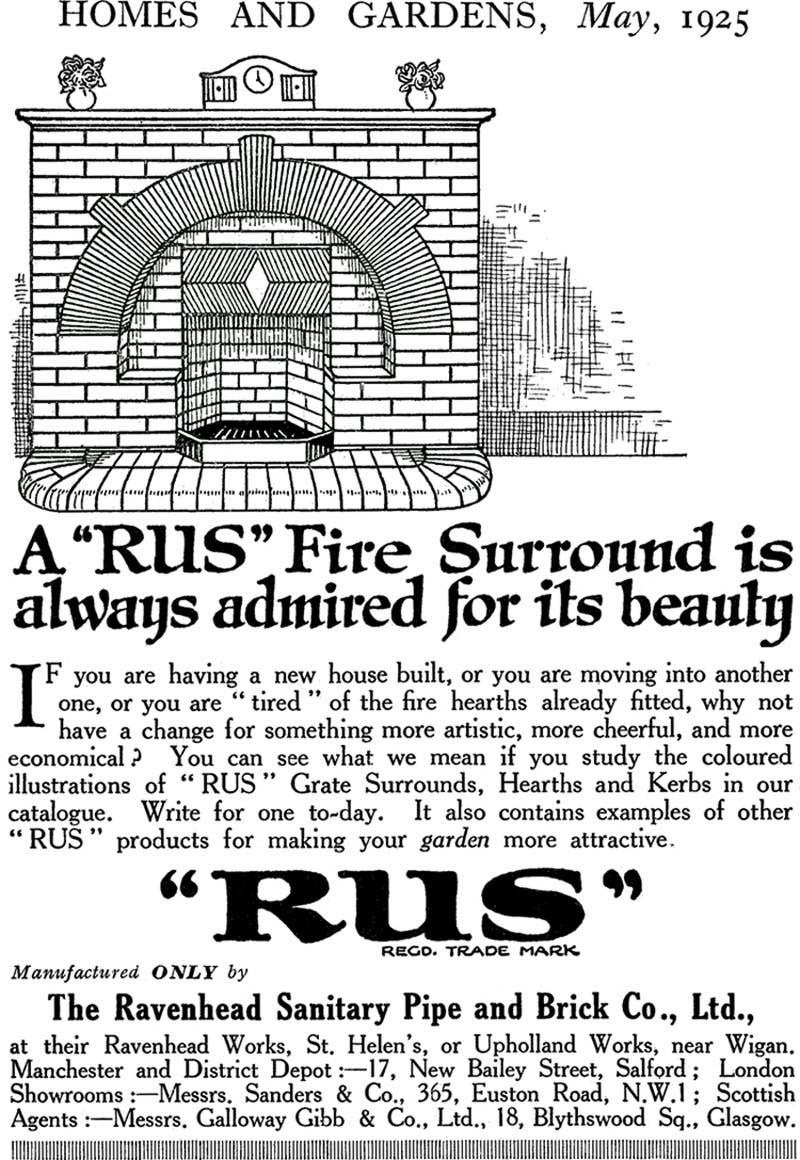

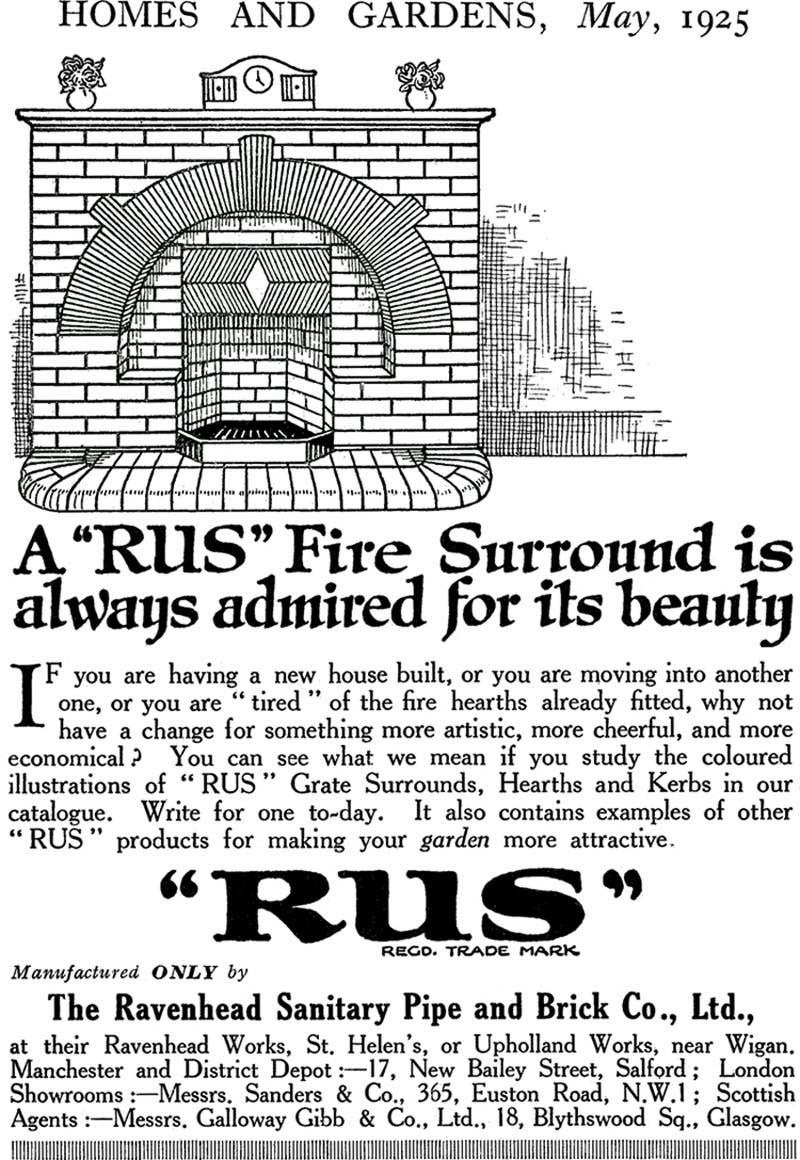

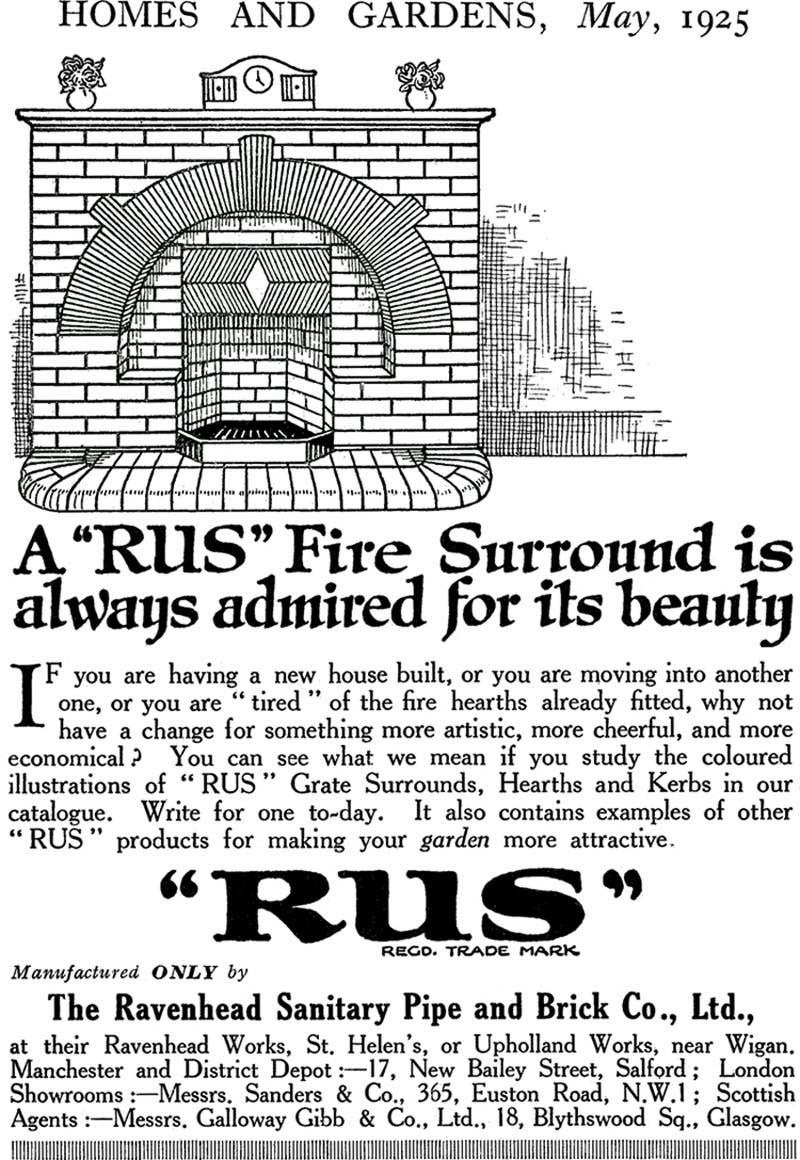

Advert in Homes and Gardens magazine for Ravenhead Sanitary Pipe & Brick Co.

Ravenhead Sanitary Pipe & Brick Co. advert in Homes & Gardens magazine

Ravenhead Sanitary Pipe & Brick advert

During the 1920s, J. J. Bate acquired the company and they rebranded their plant 'The Old Teapot Brickworks'. It did make teapots as part of their pottery operations as well as fireplace tiles and vases. However its main production was bricks, of which it made many different types, some of which were supplied to Liverpool Cathedral. The works had their own small scale mine, which had been worked intermittently since the 1880s, and which ceased operations in 1944. Production was greatly reduced during the 1950s at the Old Teapot Brickworks and it finally closed about 1967. Their clay pits were filled in 1974 and Pilkingtons Greengate Works took it over.

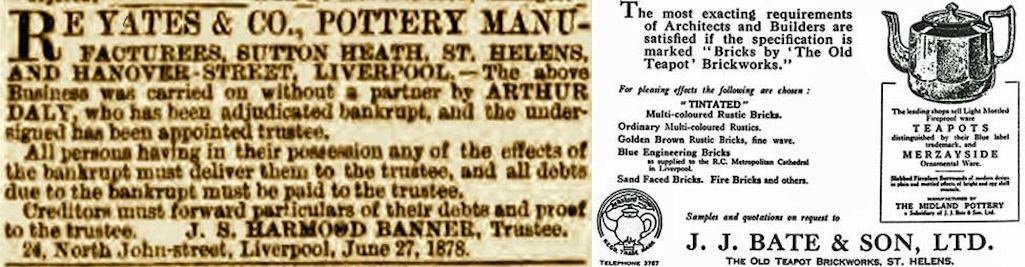

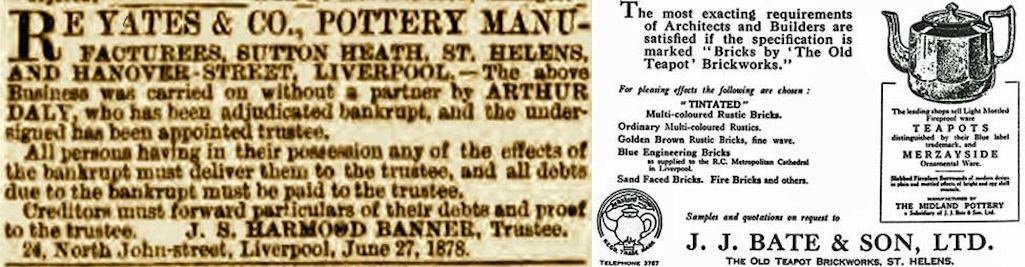

Left: Advert in the Liverpool Mercury of June 28th 1878; Right: Advert for J.J. Bate at the Old Teapot Brickworks

Left: Liverpool Mercury June 28th 1878; Right: Advert for J.J. Bate

Adverts for Yates and Co. and J.J. Bate

Providence Brickworks was situated in Binney Street adjacent to Sutton Oak Railway Station and made a wide range of bricks, tiles and pipes. North Western Estates Development Ltd., a Liverpool firm, operated the works during the late 1930s. Its engine shed was damaged by fire in February 1939 and four months later, the business was acquired by the newly-created Norwest Bricks Ltd. The manager was Arthur High, although most of their directors lived in Birkdale and the company was dissolved in 1981. There was also the Metallic Brickworks off Sutton Road and the Sutton Brick Works, which was actually in Parr, located near Gaskell Street.

Pottery works included the Marshalls Cross Pottery Co. (close to where Sutton Academy is now) and the Sutton Drain, Tile & Garden Pot Works in Moss Nook. The latter appears to have been started by John Woods and then run by William and Ann Woods until its closure on November 1st 1898. Richard Holmes Twist had a pottery works in partnership with A. Wood in Mill Lane, Sutton Heath, which on November 8th 1900 suffered a huge explosion. A boiler blew up and flew 30 yards over workers' cottages into the roadway and bricks were recovered 200 yards away. Miraculously no one was hurt.

There used to be a street in Sutton called Swaine Street which was named after the family who founded the original Sutton Heath Pottery early in the 19th century. In August 1872 the Swaines leased their business to brothers' Thomas and Francis Grace who had their own pottery firm in Marshalls Cross, begun by their father James. By 1861 23-year-old Isaac Grace had succeeded his father (who was now living in Robins Lane) and in his census return for that year described himself as a 'Potter Employing 11 Men, 9 Girls And 6 Boys'.

Isaac, who had been born in Bold, was made bankrupt in 1862 with debts of £2,300 and sent to Walton prison. The family seem to have overcome this setback with Thomas and Francis taking over the reigns. The founder of the St.Helens Newspaper, Bernard Dromgoole, had previously worked at Grace's Pottery and married the boss's daughter.

The Davies family owned the second Sutton Heath Pottery, which had originally been known as Yates & Co. The latter had been managed by an Arthur Daly but went bust in 1878. Thomas Davies had worked at Yates and served as manager for a period and he bought out the lease, with his son Richard later purchasing the pottery freehold. At one time Richard owned and worked four potteries in the Sutton area, having bought Swaine’s old pottery and two potteries that had originally belonged to the Grace family. These included Marshalls Cross Pottery, which his son Richard Jnr. ran.

In a 1951 advertisement the company (trading as Richard Davies & Sons at Sutton Heath Pottery) claimed to have been established in 1870, which was probably when Yates was founded. Richard Davies Jnr. was succeeded by his youngest son Albert Davies, who worked the pottery until 1969. The Twist family are related to the Davies family of potters and both families worked potteries in the Prescot area before Sutton.

b) Glassmaking in Sutton

It is thought that a French Huguenot family began the first glassmaking in Sutton. The Protestant Huguenots were driven out of France from 1685 and in 1688 records reveal John Leaf Snr. paying the Eltonheads £50 for a lease of 2½ acres of Sutton's Lower Hey. The Leafs real surname was probably Lefèvre and they sourced sand, coal and fireclay from the site with only alkali having to be imported.

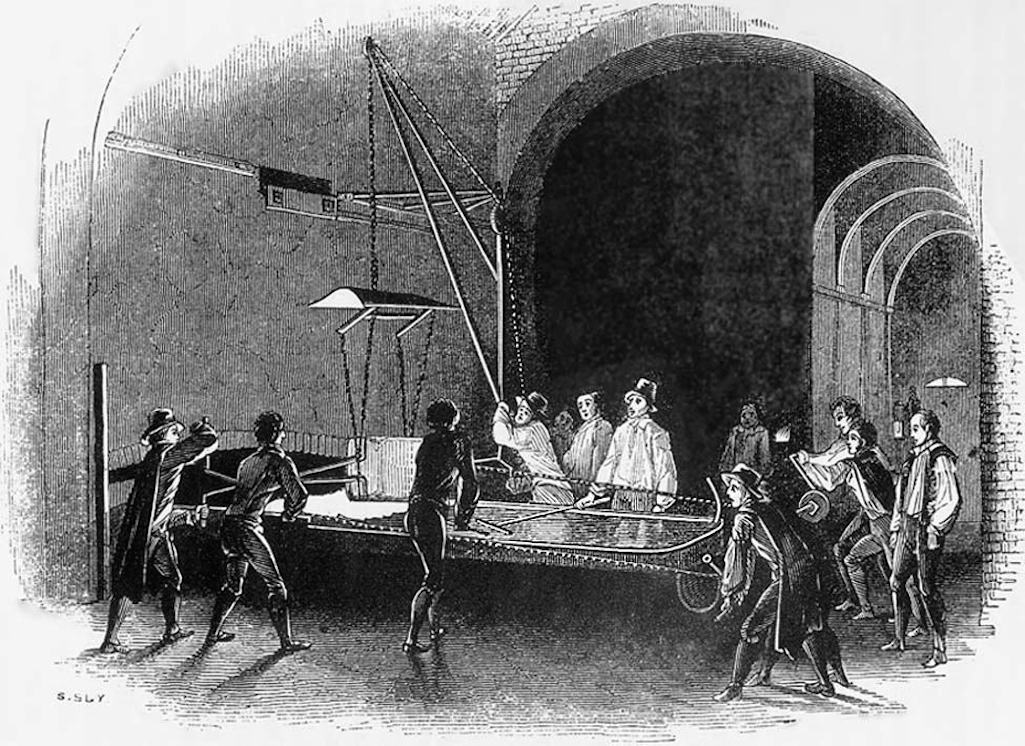

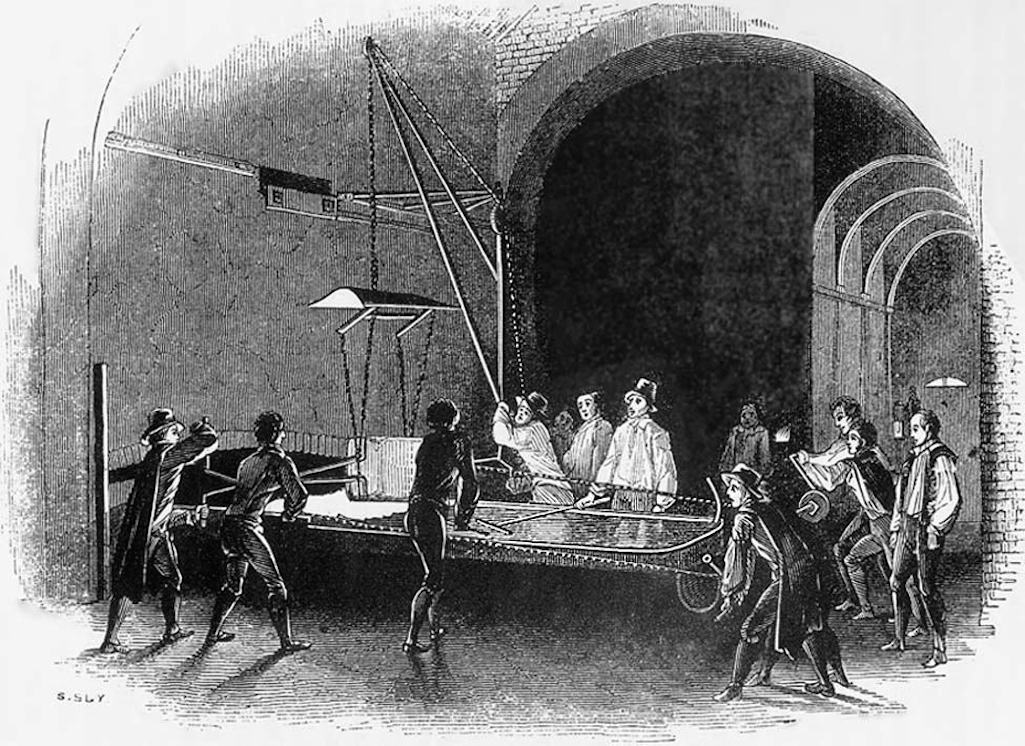

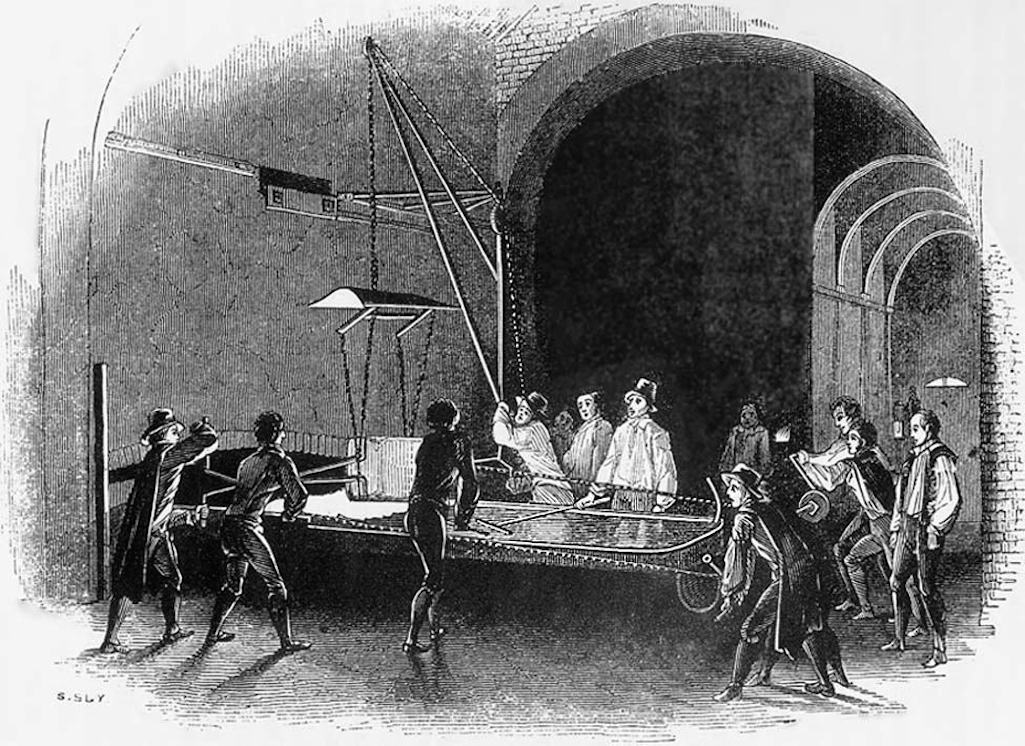

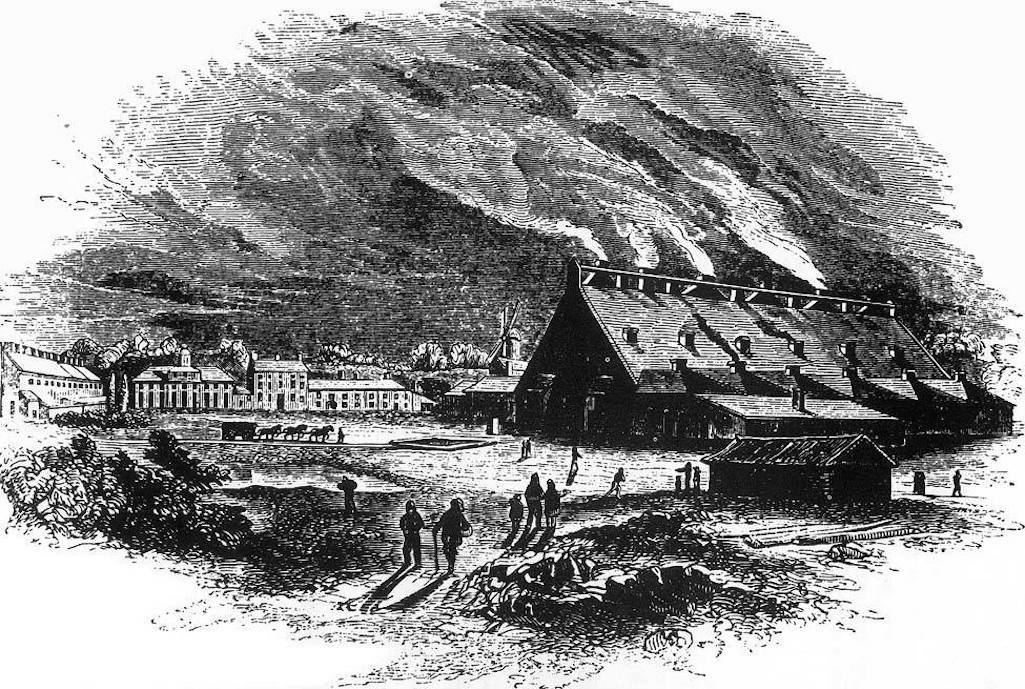

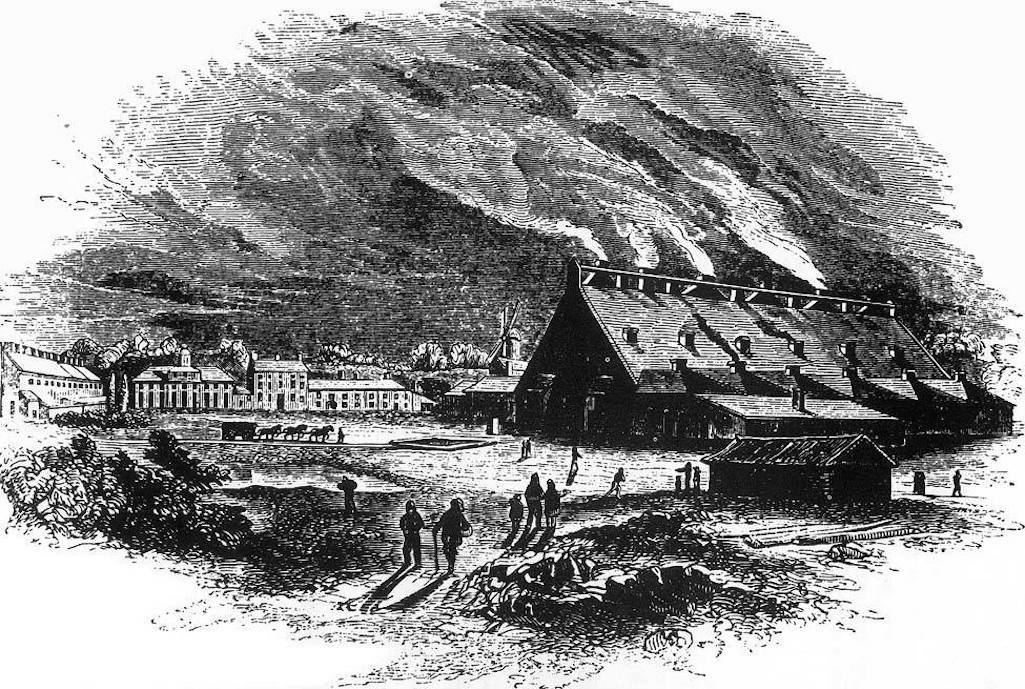

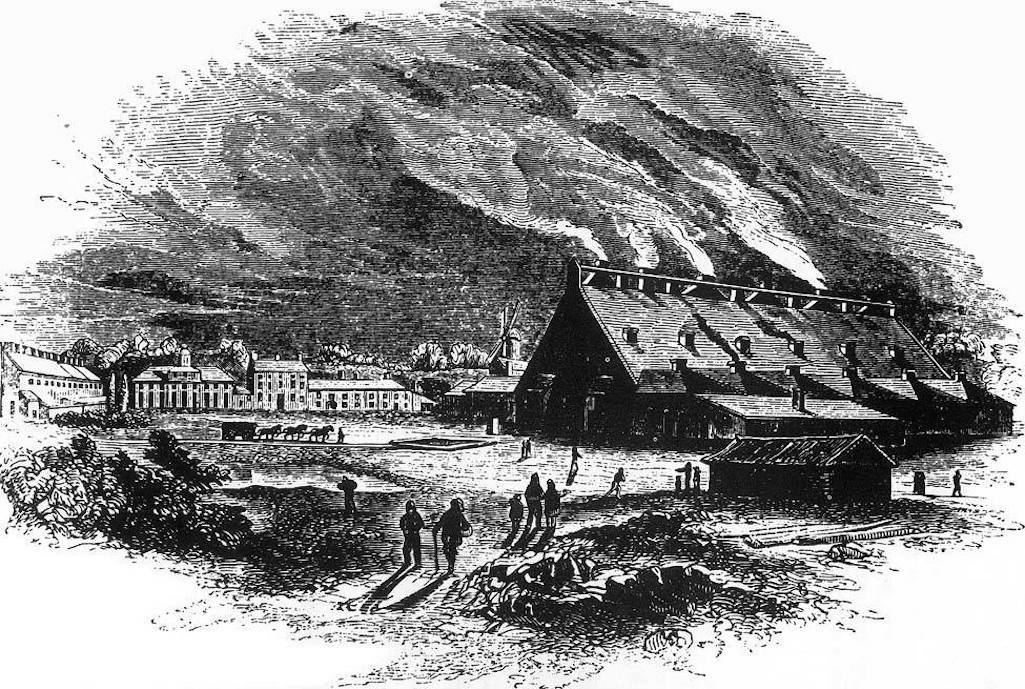

An illustration showing the casting of glass at the British Cast Plate Glass Company in Ravenhead

Casting glass at the British Cast Plate Glass Company in Ravenhead

Casting glass at the British Cast Plate Glass Company in Ravenhead

Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Francois Graux de la Bruyere was believed to have been the first manager of the glassworks and his tomb is in St Helens Cemetery. However the company got into financial difficulties and in 1798 the British Plate Glass Company took over the business. Under the new management, the Ravenhead plant became very successful and early in the 19th century (pre-1811), it received a visit from the Duke of Wellington and the Prince of Wales (later George IV). In later years Princess Alexandra, the Queen of the Netherlands and Richard Seddon, the New Zealand Prime Minister, paid separate visits to the works.

The article described how a 'vast body of melted glass' was poured from an 'immense crucible' upon the perfectly level casting table and then a large copper roller was passed over it, spreading the glass out into a 'sheet of uniform breadth and thickness', with its smooth surface exhibiting a variety of colours. Each of the cooling ovens measured 16 feet wide and 40 feet deep and their floors were level with the top of the casting table. This was on castors, so it could be moved to the mouth of an oven and a plate of glass slipped in, so it can be gradually cooled over a period of two weeks. The plate is then ground to a more exact level with sand and it's then polished with emery, tripoli and putty.

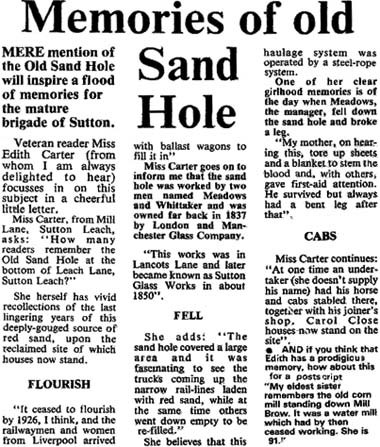

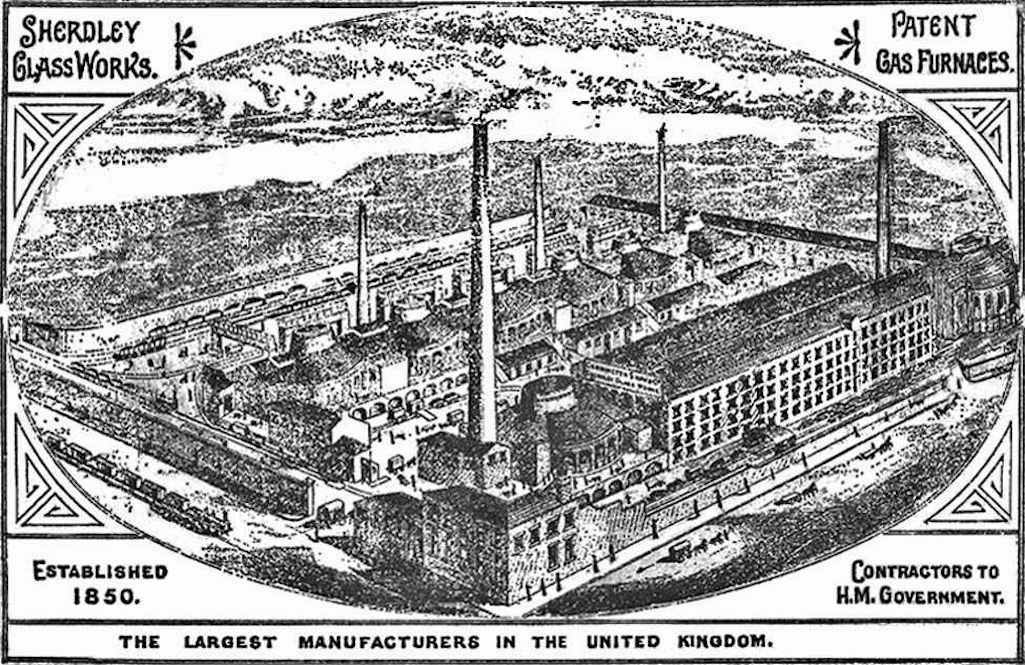

In 1836 a second plant was built at Sutton Oak by the Manchester and Liverpool Plate Glass Company. However, it closed just five years later through the depression of the early 'forties. In 1845 the London and Manchester Plate Glass Company bought the plant, paying less than half the original cost of the works. Under experienced manager George Wadsworth, the Sutton Glass Works slowly became successful. The removal of the Window Tax in 1851 boosted their order book and then the astute management of William Blinkhorn extended operations. By 1855 it was the largest plate glass works in the country with 1500 men employed. Then in 1868 the plant was further expanded and the addition of the 'extension works', as it was known, led to the site covering both sides of Lancots Lane.

The British Cast Plate Glass Company's plant in Ravenhead which was then part of Sutton township

British Cast Plate Glass Company in Ravenhead, then part of Sutton township

British Cast Plate Glass Co. plant

On August 25th 1855 the Liverpool Mercury told how 500 of the Sutton glassworkers had been treated to their annual excursion by their employers. They'd travelled by boat to Bangor 'animated by a band of music' with the day spent in 'rational and healthy recreation'. However on the same day that some staff enjoyed an outing, James Tickle's inquest took place. The glassworks stoker lost his life when he was crushed between the buffers of two wagons. In 1858 there was an investment in new technology at the Sutton works with glass polishing machines purchased. It was intended that their use would reduce the need for women to polish glass manually by moving it back and forth on large, smooth stones.

However machines needed operators and 24-years-old Louisa Eden lost her life on February 8th 1858 when her dress was drawn between the wheels of a polishing machine by a draught of air. Louisa, who'd travelled from London to operate the machine, was immediately whirled round its main shaft. Her screams brought help but it was some time before she could be extricated from the machine and was soon dead. On May 2nd 1861 further improvements to the works led to eight workmen being seriously injured. The bricklayers and labourers were erecting three large furnaces for annealing glass when the building collapsed on them.

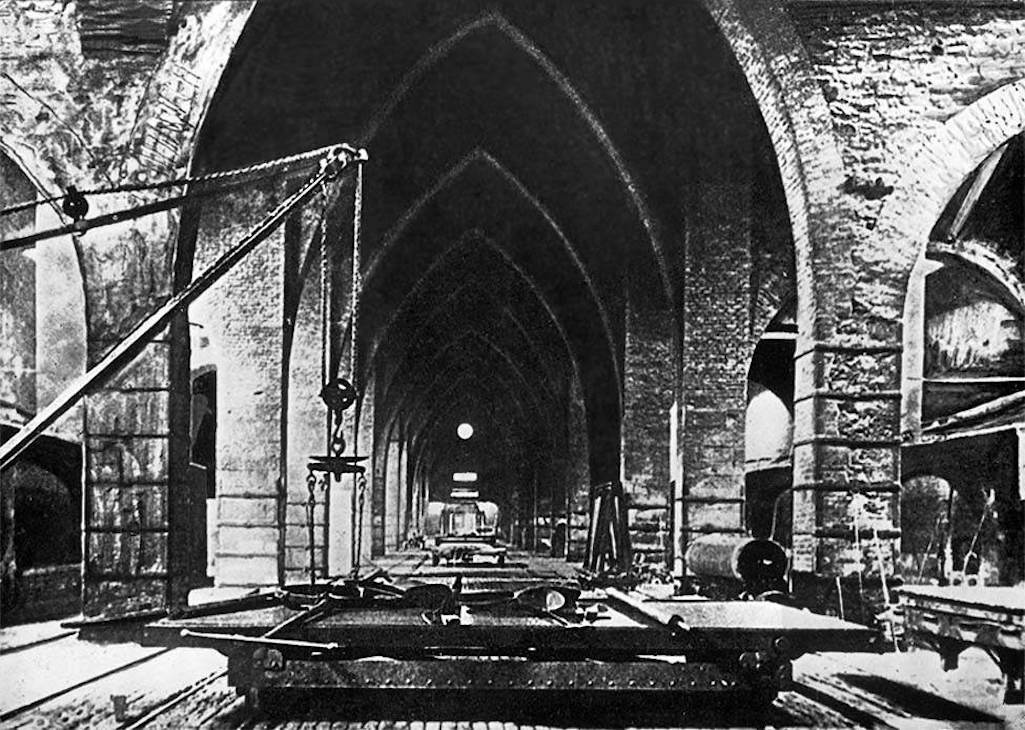

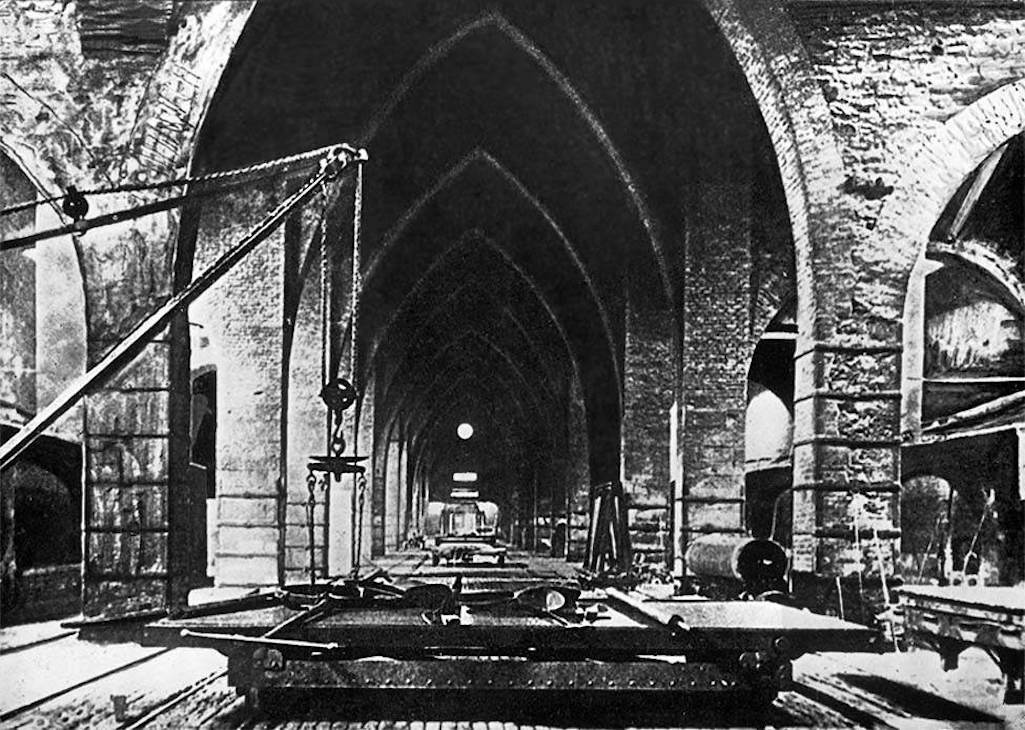

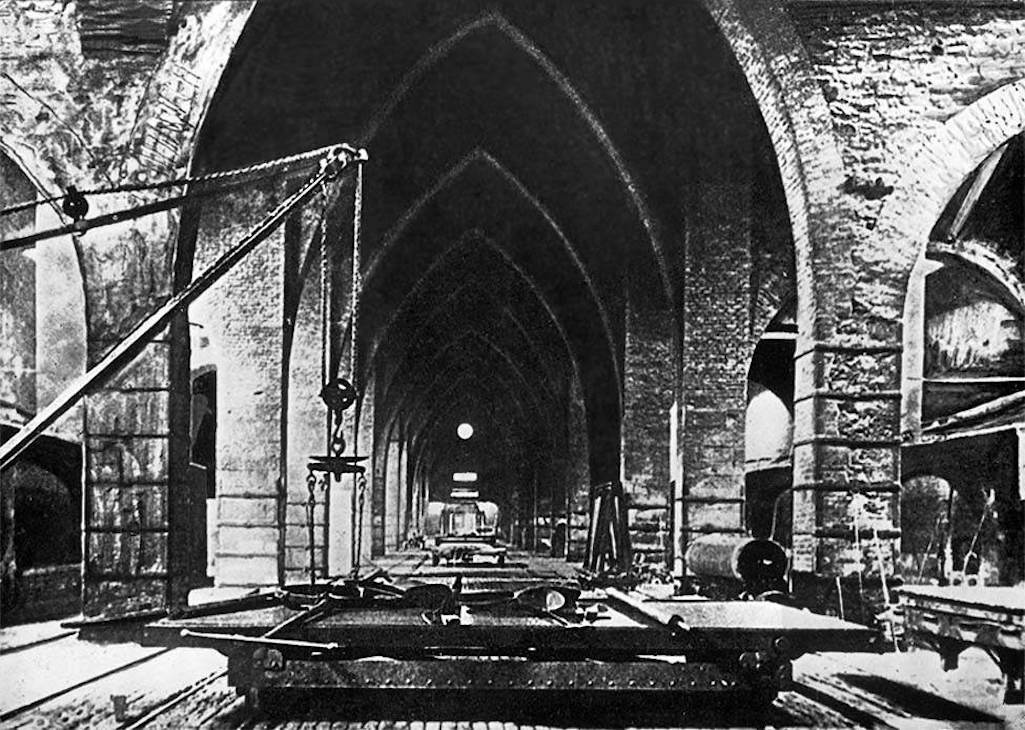

The casting hall of the Ravenhead glass works which when built was 113 yards long and at least 50 yards wide

The casting hall of the Ravenhead glass works which was 113 yards long

Ravenhead glass works casting hall

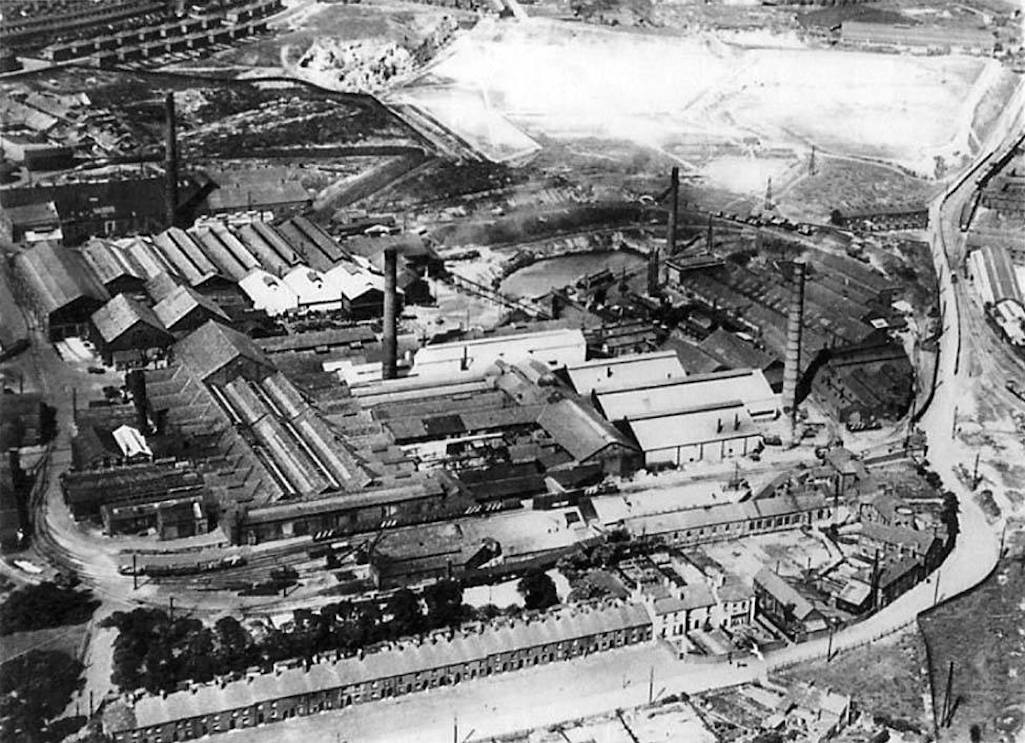

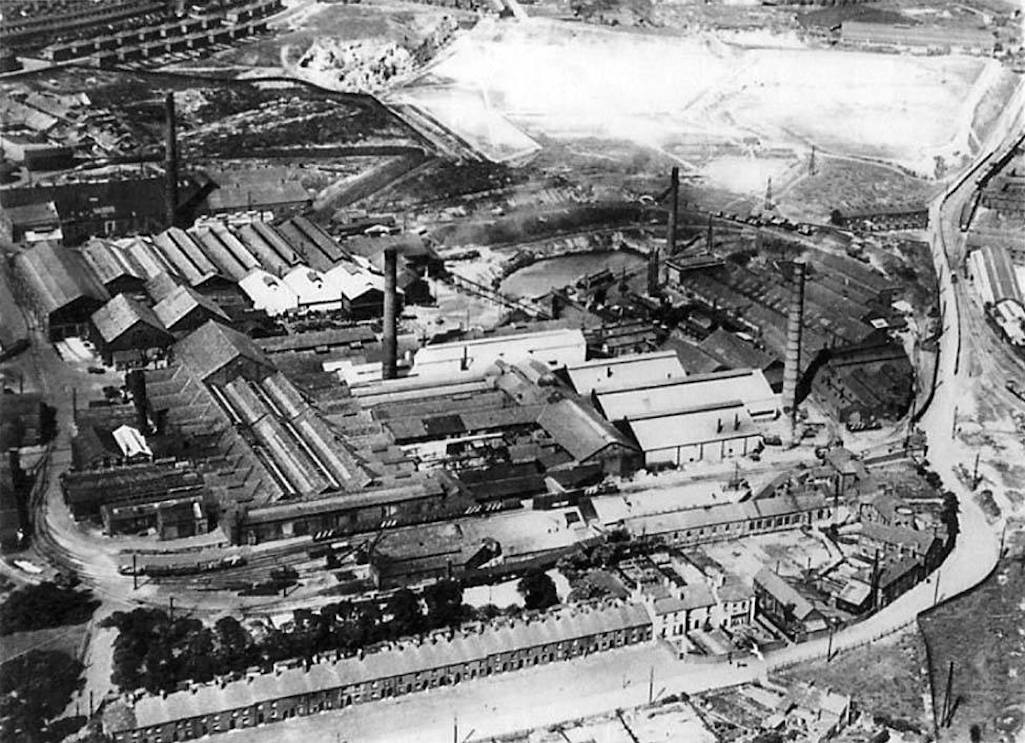

An aerial view of the Ravenhead glassmaking plant during the 20th century when owned by Pilkingtons

Aerial view of the Ravenhead glassmaking plant when owned by Pilkingtons

The Ravenhead glassmaking plant when owned by Pilkingtons

The quality of finished glass is very much dependent on the purity of the sand used in the production process, with even a very small presence of impurities such as metallic oxides causing a colouring of the glass. So the Sutton Glass Works is believed to have used one of their reservoirs to wash sand with sedimentation processing, in order to remove grit, oxides etc. A system of brick-lined tunnels was created, covering an area of about 150 x 50 yards and 3 feet 6 inches high, through which warm air was delivered to dry the wet sand. These stayed in place until after WW2 and many a schoolboy enjoyed playing in them!

High quality glassmaking at this time was an expensive business and by the 1880s, with increasing competition from Belgian and French glass plants and locally from Pilkington's and the Union Plate Glass Co. in Parr, the company began to encounter financial difficulties. The price of glass in 1887 was 45% less than it had been in 1876 and then there were further drops in the early '90s.

A strike which began in December 1888, when workers demanded a rise of 10% in their wages, virtually closed the Sutton plant and further damaged its economic standing. The strike leaders said that over the previous nine years, the workers’ wages had been reduced by 25%. They argued that the glass trade was now improving, so they were entitled to an increase. This was said to have been the first strike in the history of the Sutton Glassworks and it ended in mid-February 1889.

On December 21st 1889 the St.Helens Reporter reported the death of Peter Tasker, who they described as the ‘father of Sutton Glassworks’. The 75-year-old was among the first of the workmen engaged at the glassworks and had retained his position up to his death. In December 1891 a £200,000 investment in new equipment for both of the London and Manchester Co's plants was proposed, which would take several years to complete. All three of St.Helens’s plate glass producers had for some time been complacent against the threat of foreign competition. While local firms had relied upon the quality of their product and pre-eminent position within the glass-making world, the Belgians had been investing in new plate glass plants and improved processes.

All three companies were now furiously engaged in a race to re-equip their plants and create more efficient means of working. For example, the processes of grinding, smoothing and polishing had been carried out in different departments using separate machinery over several days. Consequently large sheets of glass up to 15 feet long had to be conveyed from room to room and onto railway wagons leading to breakages and even deaths.

In October 1891 glass labourers John Twist and 19-years-old David Lunt died in hospital from the severe injuries they'd received when plate glass fell off a wagon onto them. The accident at Sutton Glass Works broke 19-years-old Lunt's spine and an iron lever penetrated right through 22-years-old Twist's body. When the improvements had been implemented, all processes would be carried out by a single machine within a single day in the same place, reducing the cost of production and improving safety.

Efficiencies meant job losses and 200 women were discharged from the Sutton and Ravenhead plants early in 1892. They also closed the work's school at Ravenhead that year as the building, where 500 pupils were being educated, was required to extend the works. Although production costs were reduced by about 30%, by June 1893 the price of glass was 40% less than it was in 1891 and things went from bad to worse. On August 15th 1894 a notice was posted at both the London and Manchester Co's plants:

The London and Manchester Plate Glass Company went into liquidation later in 1894 and a wave of depression affected many Sutton families. The St.Helens Newspaper commented that 'destitution is developing in our midst at a rapid rate' {15/9/1894}. The annual meeting of subscribers to the St.Helens Charity Organisation held on October 29th 1895 revealed the scale of the suffering. In the ten months prior to November 20th 1894, the society had received 363 applications for assistance of which 235 had been granted and £41 paid out.

While from November 20th to December 31st 1894 with many men thrown out of work, 1303 applications for assistance were received of which 1157 were accepted and payments totalling £276 awarded. In total during the year, 534 glassworkers requested financial assistance for their families. A special relief fund had been opened by the Mayor Cllr. Henry Martin which raised £1150 in cash and £146 in kind.

In June 1896 a consortium purchased both plants for £150,000 and the London and Manchester Plate Glass Company Ltd. arose from its predecessor's ashes. The glass works eventually went back into production and the Sutton community breathed a sigh of relief. In December a special service of thanksgiving was held at All Saints church, which was said to have been crowded. However the plant's revival under manager Hudson A. Binney was short-lived. It had lost clients through the 26 months of closure and it closed for good in 1903, with Pilkington's having purchased the Ravenhead works in 1901.

The Sutton Glass Works on Lancots Lane in Sutton Oak had been an enormous enterprise. The works occupied 47 acres, which were enclosed by a ten feet high wall. However the site covered 210 acres in total, including five reservoirs that were capable of holding 18 million gallons of water. It had been connected with the railway network by four sidings and it took two years after the glass works’ closure to clear up the plant. In fact it wasn’t until September 1905 that the last men were laid off. During the previous month Pilkington's had acquired the works, which raised hopes of glass production resuming. However the St.Helens glassmaker’s only used the site for warehousing purposes.

The various glassworks sourced red sand from a huge pit at the bottom of Leach Lane, where Carole Close now stands. In a Whalley's World article in the St.Helens Star on August 18th 1983, Edith Carter recalled its operations:

From around 1870 there was a major expansion in bottle-making within the Ravenhead / Sutton district of St.Helens. Francis Dixon got into the business c.1842 when he and his brother-in-law John Merson acquired the Thatto Heath Bottle Works at the age of just 22. About three years later the pair bought the Ravenhead Bottle Works on the old canal bank. This was on Grove Street on land leased from John Haddock, the owner of Ravenhead Colliery, who supplied them with coal.

Francis Dixon's great-uncle was Jonas Nuttall, a wealthy printer and publisher, who had retired to the newly-built Nutgrove Hall in 1810 and died there in 1837. Nuttall's estate was left to his nephew Thomas Nuttall, a distinguished botanist, who had emigrated to America. Provision was made in Jonas's will that if Thomas died childless, then Francis Dixon would inherit his estate. This occurred in 1859, five years after Merson had left the partnership, and it led to Francis changing his surname to Dixon-Nuttall. This was through a condition of inheritance, as laid down by Jonas, that 'Nuttall' had to be part of the family name.

a) Francis Dixon-Nuttall (1819 - 1915) founder of Nuttall & Co; b) Nuttall's glass jar lid; c) Cannington Shaw bottle

Francis Dixon-Nuttall; Nuttall's glass jar lid and Cannington Shaw bottle

Francis Dixon-Nuttall; a Nuttall's glass jar lid and Cannington Shaw bottle

On February 1st 1887, forty Swedish bottlemakers and their families, accompanied by Harry Lyon, arrived in Liverpool en route for St.Helens. Their Swedish bottle-hands even had to have a police escort when returning home from the works. On February 10th 1887, William Roberts was charged in court with assaulting Jacob Hanser and attempting to kick a Swedish woman. He'd thrown a missile at a group of Swedes as they were leaving the Peasley Glass Works accompanied by police.

By 1892 Cannington Shaw was said to have the largest works of its kind in the world with 1,188 workers and they suffered pilfering on an industrial scale. Sixteen-years-old Ralph Jackson appeared before magistrates on November 2nd 1895 charged with stealing two bottles from Cannington Shaw. Works manager Mr. Chadwick demanded that an example be made of the boy, claiming in court that around 100 dozen gross bottles had been stolen by lads and men who'd sold them onto publicans and dealers. That's 172,800 bottles! Young Jackson received a week in prison for his two bottle contribution to the company's larceny problem. On September 22nd 1898 the bottle works had a major fire with their huge warehouse burnt to the ground and 430,000 bottles were destroyed.

Cannington Shaw jar lid which may have stored sweets - Contributed by 8-years-old Alfie Atkins who found it while treasure hunting

An old Cannington Shaw jar lid which may have stored sweets

An old Cannington Shaw jar lid

In 1897 new regulations forbade such employment at night which caused immense problems for Cannington Shaw. In one court case on January 12th 1900, the company claimed that they'd been forced to close one of their shops because of insufficient boys for night-time shifts. This closure they said had led to fifty men being thrown out of work. In a report in January 1902, it was stated that that the bottlemaking firm had 'eighty or ninety' lads on their books. In September of that year Cannington Shaw suffered two serious fires within the space of three weeks, in which two warehouses were destroyed.

In 1913 the company merged with Nuttalls (and four other manufacturers) to form United Glass Bottle Manufacturers Ltd., although their individual brand names continued. During 1969 historian T. A. Owen published a series of articles in the St Helens Reporter called "Memories of Old Days in the Bottle Works". These did not go down well with former bottle hand Albert Sephton who on October 3rd had a stinging letter printed in the paper. Albert felt they had been the bad old days and should be forgotten, describing his time at Cannington Shaw's Sherdley works during WW1 as "sweated slavery for poor pay". He said he had to work a continuous fortnight on day shift from 6:30am to 5:30pm and then after a weekend off, switch to the night shift for another fortnight from 5:30pm to 6:30am. Despite this Albert said he never earned more than 29 shillings per week. "Good old days in the bottle works. Not on your Nellie!", concluded Albert.

James Prescott (left) with Bob Bridge of Cannington Shaw with their steam wagon - Contributed by James Prescott

James Prescott with Bob Bridge of Cannington Shaw with their steam wagon

James Prescott and Bob Bridge of Cannington Shaw with steam wagon

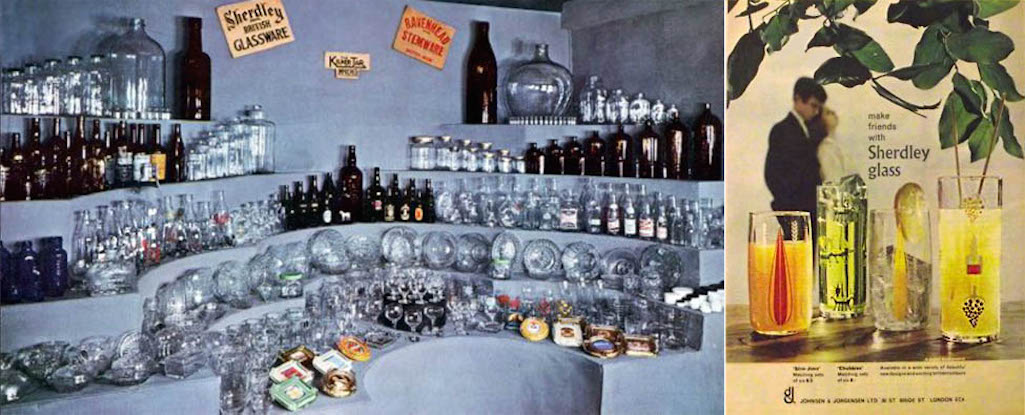

Left: Engraving a mould body at Sherdley by lathe; Middle: Fire polishing glassware; Right: Acid etching of tumblers

Left: Engraving a mould body at the Sherdley works by lathe; Middle: Fire polishing of glassware; Right: The acid etching of tumblers

Left: Engraving a mould body by lathe at Sherdley; Middle: Fire polishing glassware; Right: Acid etching

Three American glassware machines were initially purchased. One was for blowing thin tumblers and the other two were presses for producing heavy tumblers and other types of moulded tableware. There were numerous problems that the Sherdley engineers had to overcome, including discolouration caused by sulphur in the St Helens gas supply, which reacted with the alkali in the glass. The new products were immediately successful and by the end of 1933, the Sherdley range comprised 40 different types of glassware. During the late 1930s, a six-mould press was designed and made by the site’s engineers and by 1939 five fully automatic glassware machines were producing more than 100 different moulded items.

Left: Automatic mould engraving in triplicate at the Sherdley plant; Right: Packing of completed decorated tumblers

Automatic mould engraving at Sherdley and packing of completed tumblers

Automatic mould engraving at Sherdley and packing of completed tumblers

Hot-cracking-off machine at Ravenhead which removed surplus glass and created a fine rim, plus inspection & packing

Left: Hot-cracking-off machine at Ravenhead which removes surplus glass and leaves a fine rim; Right: Inspection and packing

Hot-cracking-off machine at Ravenhead, plus inspection and packing

Customers used to prefer their glass containers packed in wooden boxes that could be stored at UGB in the open air. However this changed to cardboard cartons that needed to be stored under cover and so around 1960 a new warehouse with 120,000 square feet of storage space was built. Cover was also available in two other warehouses, each with 75,000 sq. ft. of storage space.

An article published in the St. Helens Reporter in December 1963 stated that there were then 2,500 employees at the Sherdley works, which stretched across 55 acres of land. It was reported that a canteen that seated 400 workers provided meals 24 hours a day. During their leisure hours, staff could visit their spacious club in Bobby’s Lane. While discussing employees, it’s worth stating that more women were said to be employed at UGB than any other factory in St.Helens.

Workers at this time were employed in various shops making a wide range of bottles and glassware. These included large acid bottles, small syringe bottles, Maxwell House coffee jars, Dewar’s whisky bottles, green Beefeater gin bottles, pickle, jam and sauce jars, as well as pop, wine and clear beer bottles.

A further blaze affected the Sherdley works on August 23rd 1964, which was fought by 60 firemen. On July 31st 1967 the Daily Express wrote about Ravenhead Glass: 'With monster automated machines that delicately turn a "gob" of molten glass into a glistening goblet in seconds, Ravenhead is claimed to be one of the world's most advanced glassware factories.' Nearly 3 million glasses, tumblers and other tableware items were then produced at Ravenhead each week, which was double the output from 10 years earlier. Also during the 1960s, part of the Sherdley Glass Works was redeveloped and connected to a re-constructed Peasley Glass Works.

The St Helens Weights and Measures office had a room at United Glass (UGB) where they measured between 12 and 16 million pint glasses each year. Every glass had to be checked to ensure that it contained just over a pint before it was able to leave the works.

The St Helens Official Guide of 1973 stated that almost 3,000 people were employed at UGB: ‘The Peasley / Sherdley factory is one of the largest in the group producing millions of bottles, jars and other containers every week in a variety of colours, shapes and sizes…Ravenhead has one of the largest single production units in the world for the automatic manufacture of stemmed glasses.’

An aerial view which was photographed in 1970 showing plumes of smoke from the United Glass plant

An aerial view from 1970 showing the United Glass (UGB) plant

An aerial view of UGB in 1970

However the shop did not have a long operational life. By 1918 it was being used as a store and during World War 2 served as an air raid shelter. The Ravenhead glassworks was closed on March 16th 2001 with 374 workers made redundant. It was then discovered that there was a 'black hole' in the workers' pension provision and in December 2007 the government announced a financial aid package. This was after a campaign led by St.Helens North MP Dave Watts and former workers.

Part of the old UGB site photographed from Sherdley golf course in 1990 - Contributed by Jim Lamb

Part of the old UGB site photographed from Sherdley golf course in 1990

Part of the old UGB site in 1990

c) Sutton Rolling Mill and Copper Works

The copper works were also known for looking after their workforce. On January 9th 1855, the Liverpool Mercury reported how 150 of the workmen and their wives had been 'plentifully regaled' with a Christmas dinner of roast beef and plum pudding on the previous Saturday night. 'All seemed well pleased with their entertainment', the paper commented.

The name of John Fenwick Allen is very much associated with the Sutton Copper Works. A native of Swansea, Allen trained as a chemist and by 1860 (if not before) had moved to Sutton to manage Newton Keates’s works. In April of that year he became captain of no. 3 company of St Helens rifle volunteer corps. A Congregationalist, he was closely involved with a Ragged School Mission and was a founder of St Helens Hospital.

One problem for the works was that the copper ores contained a proportion of sulphur. When the ores were smelted, gas was generated which created a sulphuric acid vapour when it came into contact with moisture. As a consequence, there was often damage to crops and gardens and the copper works regularly found themselves in court. On December 20th 1865, Sutton farmer George Sefton was awarded £18 18 shillings for damage to his wheat, oats, potatoes and mangold wurtzels. At the same hearing Rev. Bernard Corosi of Sutton Monastery was awarded £11 16s. and James Skirven of Sutton Glass Farm won £17 8s. On August 23rd 1869 farmer John Johnson was awarded £118 compensation from the copper works for damage to his crops.

Then on March 29th 1870 at the Liverpool Assizes, William Tipping of Bold Hall brought an action against the Sutton Copper Works. The eccentric Wigan cotton merchant was demanding compensation for smoke damage to his extensive estate from 1867 to 1869. The cost to Tipping in those three years was estimated by him as £84, £31 and £57, respectively – £172 in total.

The defence of the copper firm was that there was more than forty works near Bold Hall that emitted vapours of a more noxious character than they did. Tipping's lawyers claimed that the smoke that shrivelled up the vegetation at Bold had been traced to the copper works but knew they couldn't prove it. In the end the jury decided that the copper works was only partly responsible for the damage to Tipping's crops and vegetation and awarded him compensation of just £22 10s.

A week later the men at the copper works made a presentation of a family bible to John Fenwick Allen. This was in appreciation of his efforts at the Assizes and the bible bore the inscription: "Presented to J. Fenwick Allen, by the Workmen of the Sutton Copper Works, as a token of their esteem for his exertions in keeping the men together when oppression and injustice would have separated them." The copper works band played a few numbers at the event where it was also pointed out that there had been "not a quarter of the drunkenness and dissipation" amongst the workforce since the arrival of Fenwick Allen.

On September 30th 1891, twelve-years-old William Dean died in hospital from the injuries that he'd received at the copper works. The young plumber's assistant fell from a fifty-feet high scaffold onto a platform below. The copper works had a chimney 183 feet high and on August 8th 1892, steeplejack Ralph Woods fell from it to his death. You can read 'The Drunken Steeplejack' article here.

Sutton Copper Works closed in December 1895 and in a sale advertisement two years later, the site was described as being on triangular-shaped land measuring 2 acres and 1 rood, with a railway on two of its sides and a main road on the third. There were sidings connecting to the railway as well as 'fine chimney shafts, principals' and clerks' offices, watchman's residence, and boundary walls'.

The McTear family at their home Roughdales Farm in Chester Lane, Sutton, St.Helens

The McTear family at their home Roughdales Farm in Chester Lane, Sutton

McTear family at Roughdales Farm

In the photograph above, James Wilton McTear shows off his family for the camera with his wife Eliza. McTear (1837 - 1916) was both the manager of the Sutton Rolling Mill factory (which he ran from the age of 23) and of Roughdales brickworks. The picture was taken at his home in Chester Lane called Roughdales Farm (a.k.a. Milestone House) opposite Four Acre Lane. The farm had eight acres and the family stayed until 1894 when they moved to Micklehead Green and St. Michael's House & Farm.

Workers outside the Sutton Rolling Mill factory c.1924 - Contributed by Ian Jones

Workers pictured outside the Sutton Rolling Mill factory taken about 1924

Workers outside the Rolling Mill c.1924

The above photograph features the grandfather of Ian Jones who has contributed the photograph. He worked at the Rolling Mill after returning from being a prisoner of war in WW1 and, like many in the workforce, enjoyed his pint in the Coppersmiths Arms which was opposite the plant and nicknamed 'Bobby's'. Ian writes that it was a race on Fridays for the women to get to the men before they could cross the road and spend their wages in Bobby's!

William Thomas served as Thomas Bolton’s works manager during the 1930s. Eric Foster, a 27-year-old ‘hammer man’ of 20 Joseph Street in Sutton, died on February 23rd 1939, a couple of weeks after being ‘terribly injured’ by a machine in the works’ rolling finishing shop. On November 20th his widow Mary was awarded £1000 in damages at Manchester Assizes after taking legal action against Thomas Bolton.

Thomas Bolton & Sons factory front pictured in the '80s, then run by SD Graphics - Contributed by Dave Latham

Thomas Bolton & Sons factory front in the 1980s, then run by SD Graphics

Thomas Bolton & Sons factory front

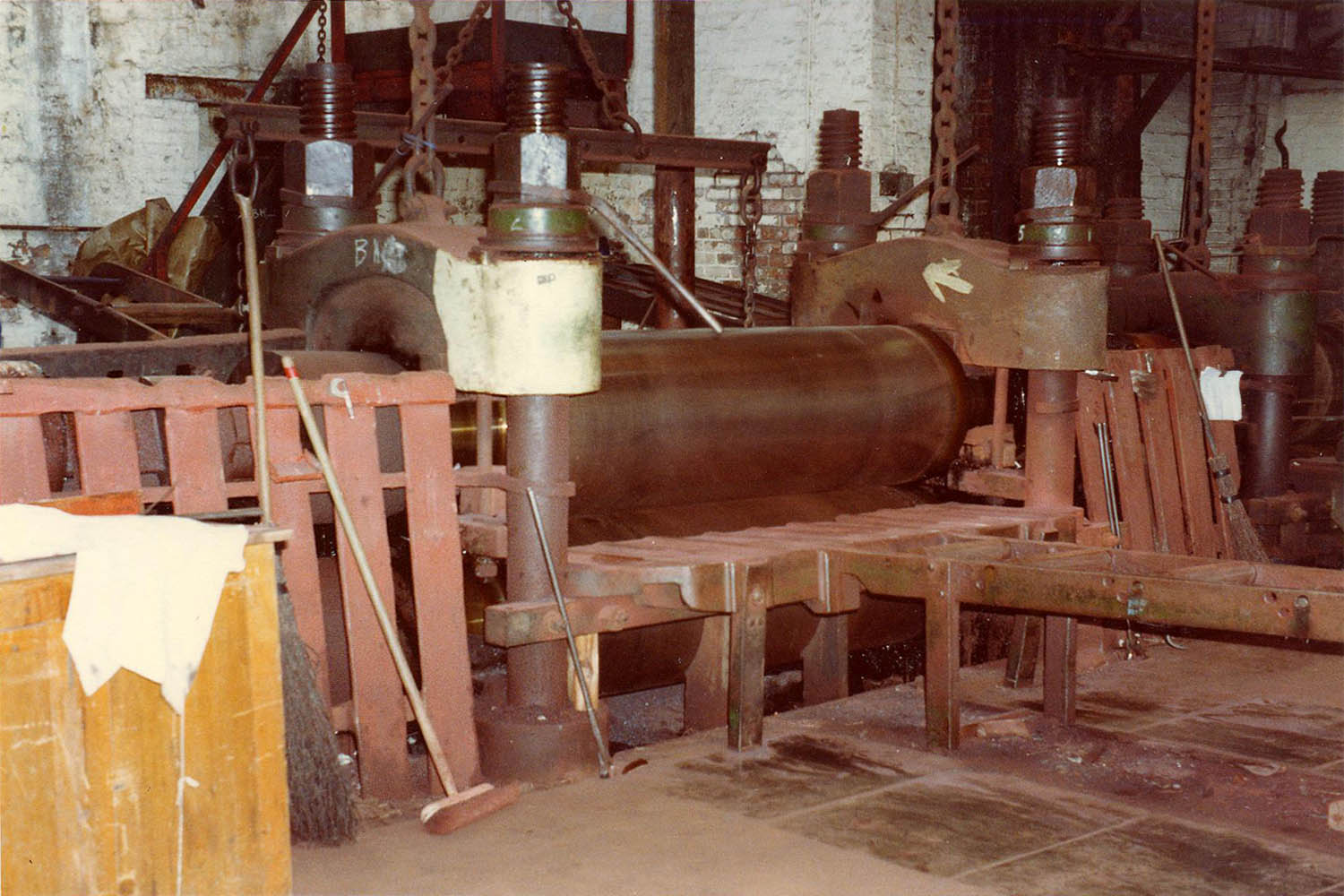

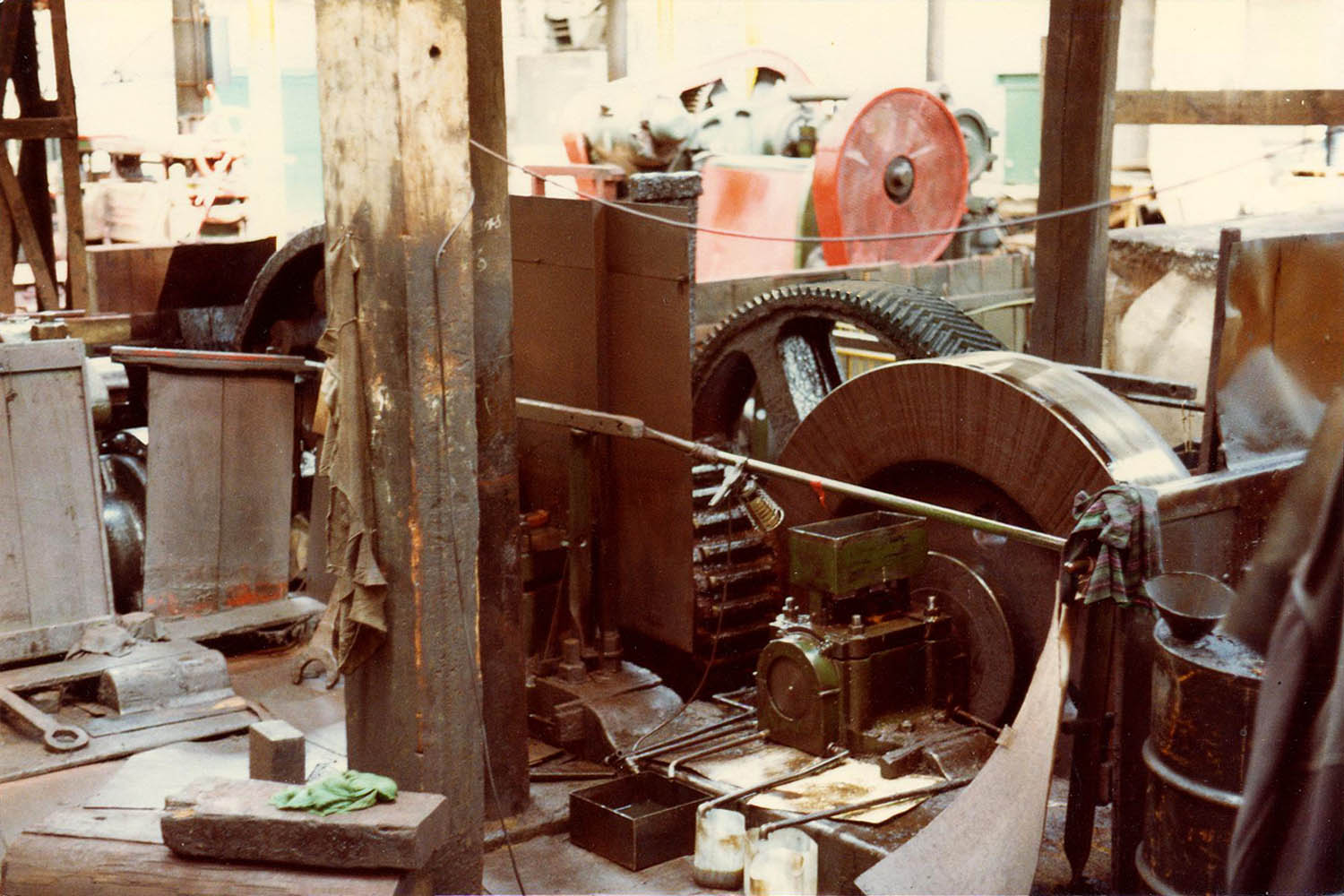

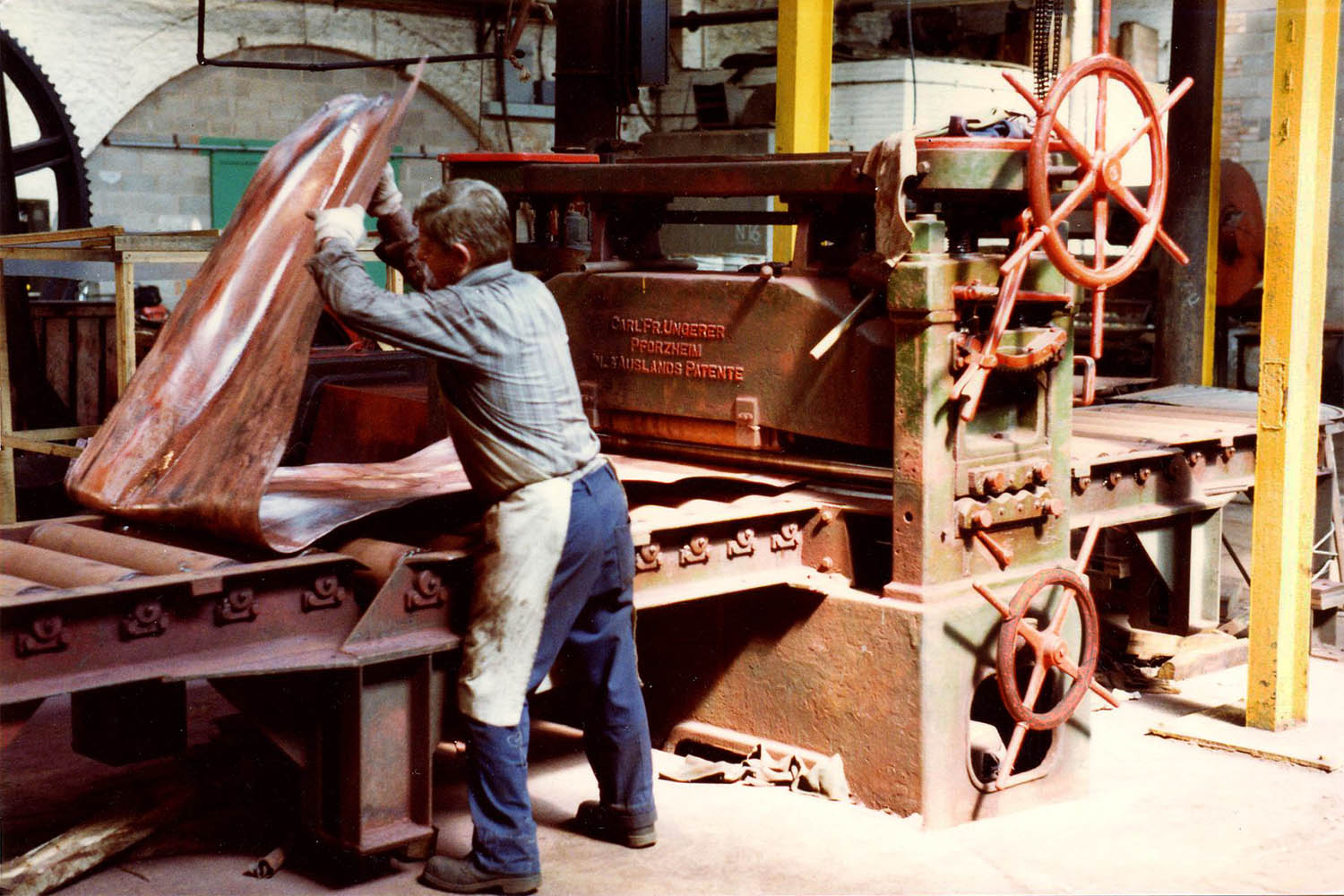

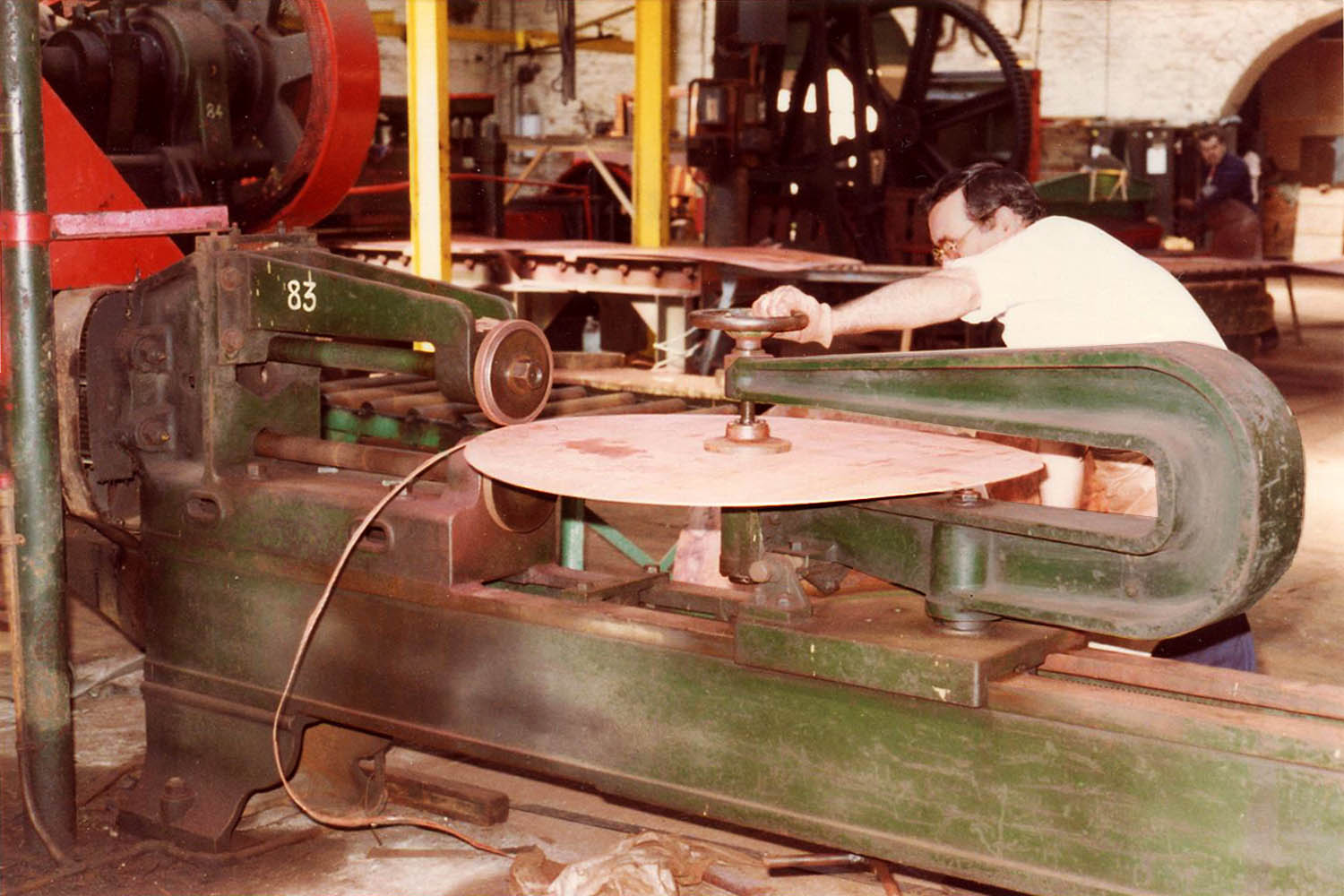

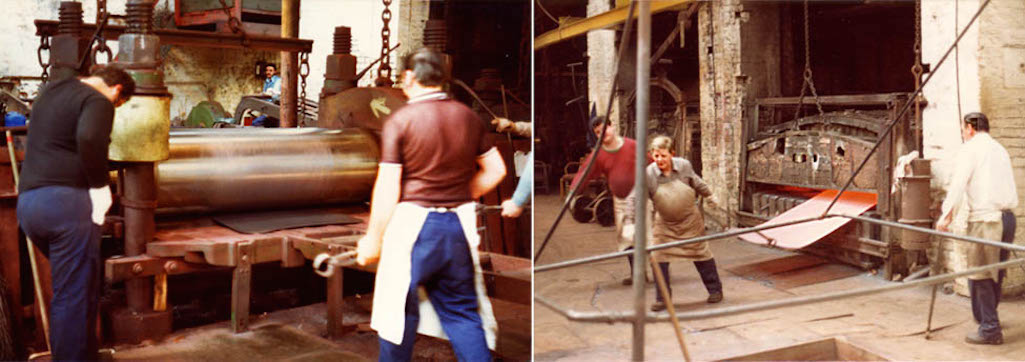

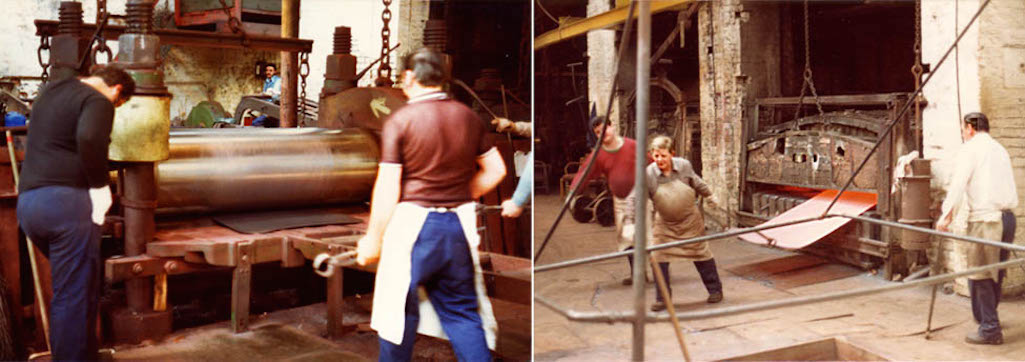

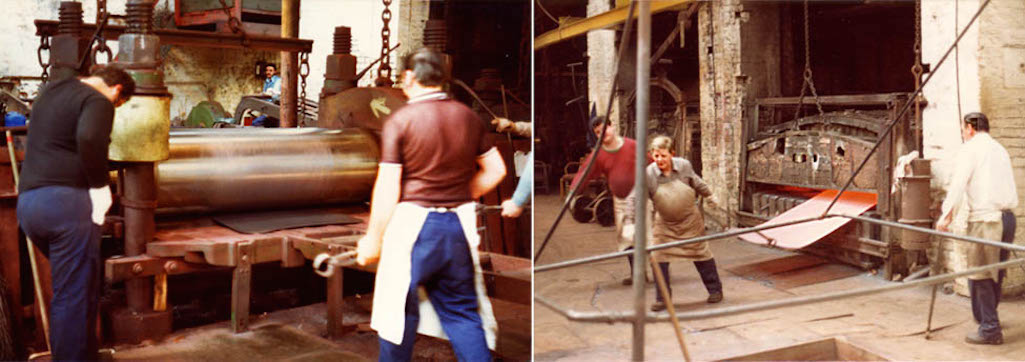

SD Graphics in 1982: Left: Rolling a copper sheet; Right: Pulling hot sheet out of furnace - Contributed by Ken Davies

Rolling a copper sheet and pulling a hot sheet out of the furnace in 1982

Inside SD Graphics in 1982

There was also the Bold Copper Works, at St.Helens Junction, which was initially run as a partnership between Alfred Paget, Walter Critchley and Charles Swaisland. After the latter had resigned, the St.Helens Smelting Co. Ltd. was created on June 20th 1862 and they began to run their works more vigorously. The company was situated a mile from Bold Hall and half a mile from its estate boundary and soon damage to the estate from the smelting company’s chimneys was discerned.

William Tipping, owner of Bold Hall, brought an action against the firm in August 1863, demanding compensation for the effects on his trees, hedges and cattle from the company’s ‘destructive noxious vapours’. Tipping was awarded £361 damages and the St Helens Smelting Company then appealed to the House of Lords. In what is considered to have been a landmark judgement that still has repercussions today, the Lords rejected the appeal and then the Court of Chancery in 1865 granted Tipping a restraining injunction.

This effectively halted the operations of the St Helens Smelting Company and as a result the firm chose to relocate to Ravenhead. They took over the recently vacated copper works of Bibby and Co., who had built a new factory a short distance away down the canal. The St Helens Smelting Company’s old factory at St Helens Junction would later be used to manufacture manure products.

William John Thomson (1840 - 1915) was for many years the manager of the St Helens Smelting Company, living at Ghyllbank, near Knobstick Hall in Sutton. He was passionate about orchids and Myrmecophila Thomsoniana, the endemic orchid in the Cayman Islands, was named after Thomson, who grew the first plant to flower in the UK.

d) Chemical and Alkali Works In Sutton

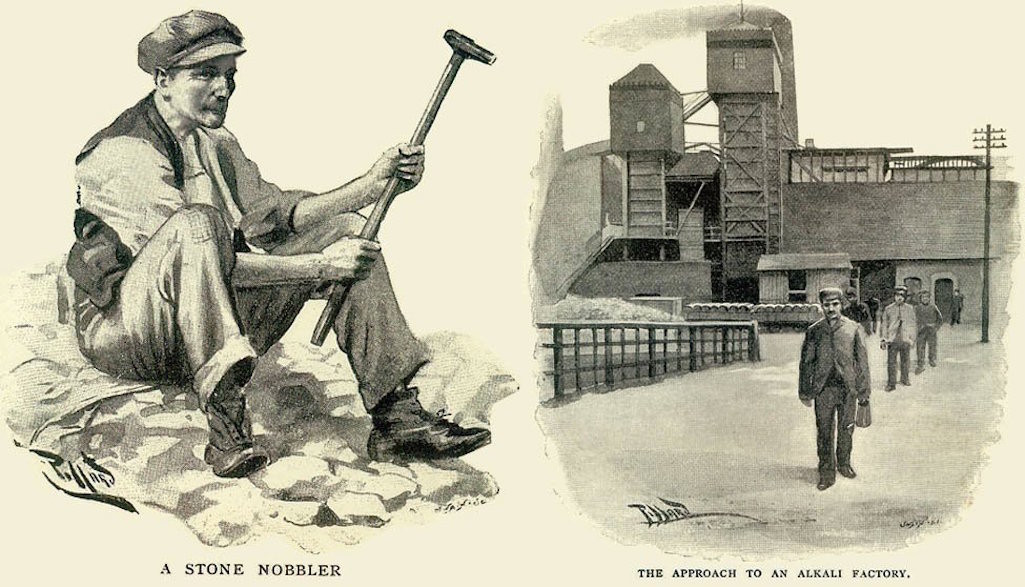

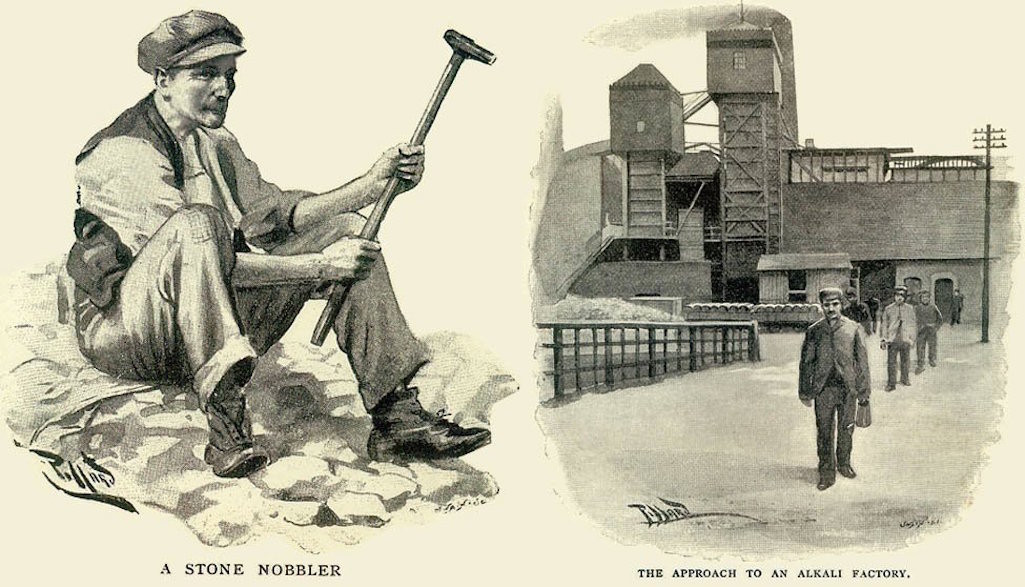

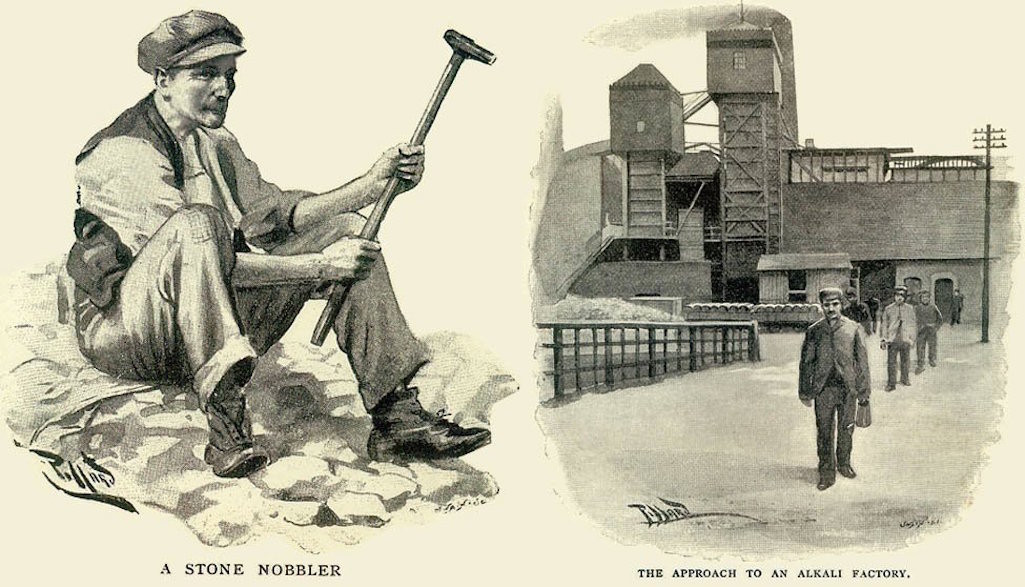

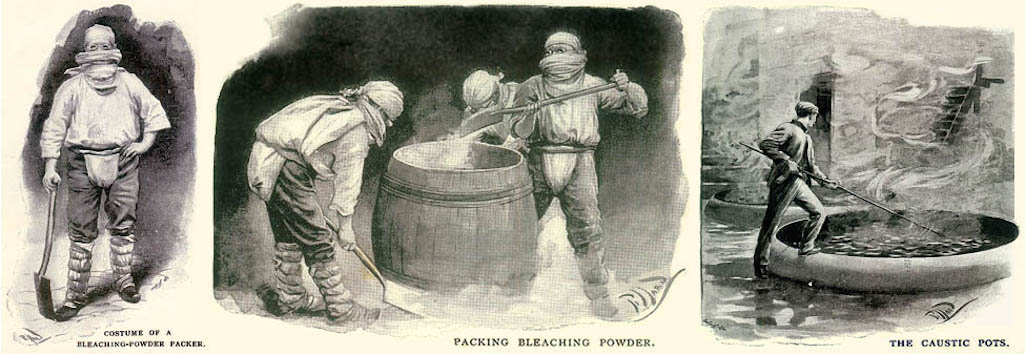

By the 1890s the towns of St.Helens and Widnes were responsible for three-quarters of all chemicals manufactured in Britain. During 1896 Pearson's Magazine ran a series of articles entitled 'The White Slaves of England' by Robert H. Sherard which focussed on the 'worst paid and most murderous trades of England'. For one edition Sherard paid backdoor visits to the alkali works of St.Helens and Widnes accompanied by artist Harold Piffard and his exposé could not have been more damning. Sherard’s article revealed the wretched life of the workers, including the shocking damage that the chemical factories inflicted on their health, and how the foul gases that belched from their chimneys was decimating the environment.

Illustrations by Harold Piffard who visited chemical factories in St.Helens & Widnes in 1896

Illustrations by Harold Piffard who visited St.Helens’ chemical works in 1896

Illustrations by Harold Piffard who visited chemical works in 1896

The salt-cake men were at the sharp end of the operations. Working with hydrochloric acid gas they lost their teeth within a year. One St.Helens salt-cake man who'd done the dreadful job for 18 years, described working seven days a week for just 24 shillings pay. He had to stand for eight hour shifts in front of a fiery furnace 'melting with heat', drawing, shoving and turning the salt with an iron bar that weighed 56 pounds. Another salt-cake man from St.Helens with twenty years experience, told Robert Sherard that he'd recently been sacked on the spot after he'd overslept and arrived at work late.

Pearson's Magazine claimed that the men who packed the bleaching powder 'literally carry their lives in their hands', as they were exposed to deadly chlorine gas. The packers wore goggles and 20 thicknesses of flannel over their mouths but could still only pack for a few minutes at a time. If they were 'gassed', they would likely be dead within an hour. Like all the other alkali workers, these men were piece-work paid, with the article claiming their average wages were 50% less than they'd been 5 or 6 years earlier. During the same period, the prices of the products that their hard graft produced - namely bicarbonate of soda, salt-cake, caustic soda and bleaching powder - had each risen by between 50 and 100%.

However Sherard’s report was nothing really new. In July 1894 a trade journal investigated the chemical factories in St.Helens and published an article entitled ‘British Slaughterhouses’. At the same time the Chief Inspector of Factories, Richard Sprague Oram, published his 1893 report, which was particularly damning of the chemical works. It described how workmen routinely suffered chest tightness, breathlessness, loss of appetite and coughs, which led to men spitting blood and then collapsing on the street. Those involved in making caustic soda often suffered blindness after being splashed in the face.

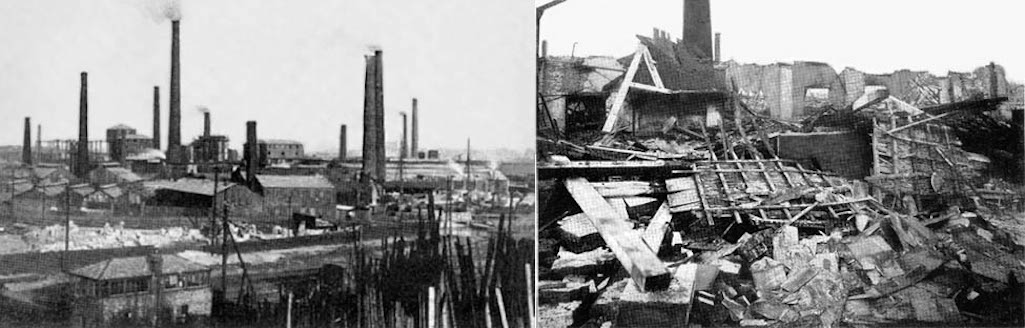

Left: Kurtz Alkali works pictured during the mid 1890s; Right: The shed where an explosion killed 8 men in 1899

Left: Kurtz Alkali works; Right: Shed where an explosion killed 8 men in 1899

Kurtz Alkali works and shed where the 1899 explosion occurred

The Sutton Lodge Chemical Works was operated initially by the Sutton Lodge Chemical Co. from the mid 1870s. The alkali works was set up by Cannington and Shaw, who sold it to the United Alkali Co. in 1891. They closed it in 1896 and the site was repurchased by Cannington, Shaw & Co as a glassworks. The Greenbank Chemical Works operated from around 1845 until 1921, when its last owners, the United Alkali Co, closed it. Other plants in Ravenhead were Marsh's Chemical Works and Bridgewater Alkali Works. There was also a short-lived vitriol works adjacent to Ravenhead Brick Works, which began in the late 1870s.

In Sutton Oak Victors Ltd. operated a chemical works in Baxters Lane, commencing operations about 1915. They were described as phosphoric acid and phosphate manufacturers and in 1920 and ’21 invested in new extensive works. Perhaps they overstretched themselves, as a petition for Victors winding up was brought in September 1922. The appointed receiver placed advertisements in newspapers inviting a sale by private contract of the 14-acre works.

The ads claimed that Victors was ‘equipped with the finest American and English automatic and labour-saving Plant’ and had been acknowledged as ‘one of the most up-to-date Chemical Plants in the world’. The sale also included four houses close to the works and an automatic barrel-making plant. Victors were again advertised in 1924 but this time it was to promote a piecemeal auction of all the plant's equipment, which was set to take place on October 15th.

Further newspaper adverts were placed in May 1929 but purely to sell the buildings that occupied 7,850 square yards and the leasehold land that adjoined the Sutton Oak Brick Works and which was now down to just over 5 acres. It was also stated that a low price would be accepted. By this time all the chemical firms were deserting Sutton and St Helens for Widnes and Warrington.

So it seems likely that a buyer for the Victor works could not be found and so the Sutton Oak Brick Works took over a large chunk of their land. They took a lease in December 1926 with Michael Hughes, so the brickworks probably expanded then. The old Victors buildings appear to have been left unused for some years, before being occupied by Stamina Foods to make pet food, biscuits and dextrin (see Other Sutton Works for details).

British Sidac are included in this section as they used chemicals within their production process and were linked to sulphuric acid manufacturer Leathers Chemicals. The company was a major employer in Sutton and by 1973, after four decades of production, had 1,600 staff working on its 40 acre site. Much of the transparent cellulose wrappings manufacturer's output was converted into plain and printed packaging materials, mainly for food and tobacco products. It is often said that they made Cellophane. However that is a registered trade name and British Sidac’s chief product in its later years was known as Rayophane.

It began as a public company on November 30th 1933 but was converted into a private company on July 23rd 1936. The firm was a British subsidiary of Société Financiére de la Cellulose S.A. Holding of Luxembourg, which in turn was a subsidiary of Société Industrielle de la Cellulose (Sidac) S.A., of Belgium. On 21st April 1939 the St.Helens Reporter described how British Sidac had celebrated their fifth birthday with a dance attended by 400 guests, which was held in the Co-Op Hall in Baldwin Street. The newspaper commented how their workforce had numbered 60 people in 1934 but was now 600.

As they employed volatile chemicals, the risk of fire was never far away. On March 20th 1959 ten fire engines were sent to the fourth fire in three months at Sidac's Sutton Oak plant. The £1 million works suffered from subsidence and by October 1959, this had led to a total of £100,000 in repairs having to be made. The company was already constructing a new £500,000 viscose plant and fearing that its buildings might also be affected by subsidence, British Sidac purchased £40,000 worth of underground coal to limit the future impact of mining on the site.

On September 22nd 1960 it again became a public company and in their share prospectus, the Sutton Oak works was stated as covering 18¾ acres, with a total floor area of 480,000 square feet. British Sidac also had 51 acres of additional land in Sutton, on which was situated its sports club, waste dumps and reservoir. A water supply was also taken from Carr Mill Dam and microstrained and chlorinated before being pumped into the delivery main to Sidac. Substantial quantities of cellulose film were supplied to E. S. & A. Robinson of Bristol, the renowned paper, printing and packaging company and it had a small export business, mainly with Commonwealth countries.

In addition to its main works in St Helens, British Sidac now also had small works in Paisley in Scotland, Wigton in Cumbria and in London and Australia. A new research block and pilot plant was completed at the Sutton Oak works at the end of 1964. However in September 1965, it suffered yet another fire. This time the blaze destroyed a major coating unit, which the company described as a “severe blow”.

In March 1969 British Sidac took delivery of a computer costing £65,000 (about £1.1 million in today’s money), which was used for record keeping, processing orders and managing the payroll. An explosion in their viscose department took place early on August 26th 1969. However there were no injuries and damage was slight.

At St Helens Town Council's meeting on March 4th 1970, Councillor Allan Lycett asked what was being done to reduce the noise that came from British Sidac in Sutton. He described the din as "devilish", adding that a stringent watch should be kept on the plant. The sounds were caused by a safety valve that alleviated a high pressure of steam and although silencers had been added, it was still noisy. Alderman James McDonnell was chairman of the Health Committee and said they would keep an eye on the situation. At the end of May 1970 Sidac announced a new wages and productivity agreement, which would give their lowest paid shift workers an average wage of £31 per 42-hour week.

The St Helens Reporter of August 28th 1970 described complaints from what they called the "acid drop dollies" at British Sidac. These were office staff who claimed that sulphuric acid bubbles from the adjacent Leather Chemicals were damaging their tights as they arrived for work. 22-year-old Helen Marsh of Dixon Avenue in Newton said: "It looked like a sea of champagne bubbles coming towards me. I was wearing boots and a mini-skirt and when the bubbles landed on my tights they just disintegrated between the top of my boots to where my skirt started. There was so much of it about it made me choke. I had to run to the lodge gates to escape the great cloud."

However Helen's experience was far from unique, as 20-year-old Margaret Gaskell of Fleet Lane in Parr explained: "It has happened quite a few times. My tights have had great holes in them when I have got into work. All the men watch us sidestepping the bubbles. Some days we get quite an audience. We try and dodge the bubbles but there are so many of them, it's a losing battle. We feel the least the chemical company could do is apologise."

Elizabeth Beard of Boardmans Lane reckoned that more than twenty of the girls had had their tights ruined by the sulphur bubbles: "It's beginning to get expensive to work here. My husband is getting worried about having to keep forking out for new tights for me." British Sidac's joint managing director, Dr. George Britten, seemed more concerned about possible damage to cars than to his employees' clothing, telling the Reporter: "We are having a staff car park built near the works and we are carrying out atmospheric tests there. Acid could quite possibly damage cars. Our company have often been blamed for the state of the atmosphere. This time we are blameless. Complaints I have received from residents about the acid I have passed on to Leathers".

In the early 1970s there was a recession in the cellulose film industry and during the financial year 1970 – 71, British Sidac's profits dropped from £1.35 million to £188,000. Low consumer demand, increasing competition, soaring raw material costs and rising wages were all having an impact on profitability and the company’s share price plunged. To reduce overheads the London head office was moved to Sutton but plans to merge with First Transparent Paper, were scuppered by the Monopolies Commission. During November of 1971 production was cut at the works because of a shortage of raw materials, caused by an explosion in a supplier’s factory.

By 1973 profits had recovered to £1.25 million but its chairman S. H. Marechal warned shareholders that the company was facing considerable increases in costs. In October of 1973, British Sidac was taken over by Belgian chemical group UCB, who already owned almost 40% of the company’s shares. This marked a full circle in the British company's history, as it had been formed in 1933 by a part of the UCB group, then known as Société Industrielle de la Cellulose. However during the early 1980s, there was a worldwide collapse in demand for cellulose film and British Sidac made heavy losses and closed its Sutton Oak plant on November 20th 1982 with the loss of 650 jobs. The site was purchased by St.Helens Council who began a clean up in 1994.

British Sidac canteen staff in early 50s - front row (L-R), Maggie Morgan; ?; Mrs Round; Annie Cook - Contributed by Ken Morgan

Sidac canteen staff - front L-R Maggie Morgan; ?; Mrs Round; Annie Cook

British Sidac canteen staff in early 50s

The hazardous chemicals that they came into contact with were carbon disulphide, toluene, formaldehyde and phosgene. Mr. Fallon stated that during his career with Sidac he never wore masks or protective clothing and had been attracted by high pay levels and often worked 7 days a week. He said the company were only concerned with fire risks because of the volatility of the chemicals, adding that "the smell was evil and there were times when I was high on a cocktail of different things". For their part British Sidac denied responsibility for James Fallon and Robert Burrows’s health problems. The company said that they settled upon the advice of their insurers to avoid an expensive trial.

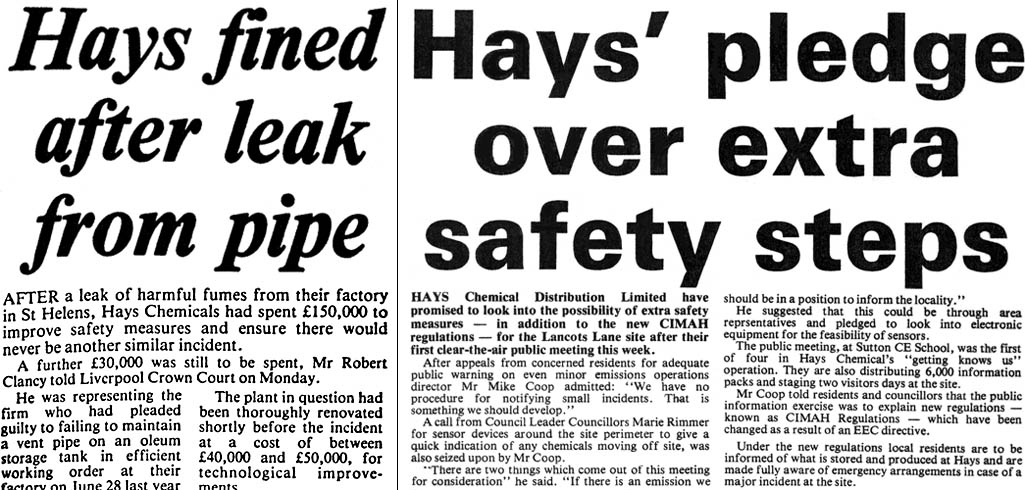

Leathers Chemicals and Hays Chemicals were both highly controversial plants, which date back to 1968. This was when British Sidac requested planning permission for a £1.3 million sulphuric acid plant to be built adjacent to their main works. They stated that surplus steam generated by the new factory would be used by Sidac’s existing plant, which would ultimately reduce the levels of sulphur dioxide generated into the atmosphere.

It was also claimed that the highly-polluted Sutton (or 'Stinky') Brook - which also produced a bad egg smell - would be cleaned up. This was because the new sulphuric acid factory would effectively recycle the sulphurous effluent liquor that was discharged by Sidac into the brook. The liquor would instead be burnt off and converted into sulphur dioxide, which would then be used as a raw material by the new plant.

It was on this basis that St.Helens Council granted outline planning permission on December 4th 1968. Ten days later the council were surprised to receive a letter, which stated that it would be Leathers Chemical Company who would be operating the new plant and not British Sidac. Leathers were a subsidiary of the giant Occidental Petroleum Corporation of California and they needed a new site after a Bradford ring road had displaced their existing plant.

The new sulphuric acid works was commissioned in February 1970 and the proposal that British Sidac would make use of excess steam generated by the new plant was enacted. However some months earlier, Leathers had informed St Helens Council that the link up between the two plants - in which liquor would be turned into sulphur dioxide - was no longer technically feasible. The net effect was that more sulphur dioxide was discharged by Sidac, rather than less, as they had promised. However they did construct an effluent treatment plant, which improved the quality of Sutton Brook.

Soon after the new sulphuric acid-making plant became operational, locals began complaining about pollution. The Lancots Lane factory was only 200 yards away from housing and there was also six primary and two secondary schools - along with St.Helens Hospital - in the neighbourhood. At first the council complained that pollution monitoring equipment had not been installed, as required by the conditions attached to the planning permission. Once the equipment was installed, the council issued an enforcement order against Leathers, alleging that sulphur dioxide emissions were too high.

The controversial Leathers Chemicals in Lancots Lane in Sutton, St.Helens which had two public inquiries

Leathers Chemicals in Lancots Lane in Sutton which had two public inquiries

Leathers Chemicals in Lancots Lane

Leo Price QC, the company’s barrister, dismissed all the allegations, stating that there was no evidence to support them. The East Sutton Residents’ Association had earlier held a protest march and demonstration. Its chairman, James Atherton, told the Guardian newspaper: "We are not going to be armchair protestors any more. This acid has stripped paint off cars, put holes in pipes, and caused coughing fits." However Leathers won their appeal but the company was subsequently prosecuted under the Alkali Acts and fined. The Alkali Inspectorate put the plant under close inspection and made 25 visits within a period of 12 months.

In March 1975 St Helens Council voted to close Leather's by revoking its planning permission under a clause in the Town and Country Planning Act. It then asked the Government for permission to borrow £3 million to pay compensation to the company. This would set a precedent for other local authorities, who had in the past elected not to rescind planning permissions from troublesome companies because of the high levels of compensation that would have to be paid. St.Helens Council wanted to spread the compensation over five years and estimated that this in total would mean a 10p rate increase for residents.

Sutton Councillor Jim Bond said: "The people of the area are so heartily sick of Leathers that they are more than willing to pay the price". He also said that their acid tankers were cleaned out with steam every night with "the fumes choking those living nearby". Sixty workers would lose their jobs if the plant closed but the hope was that some could be transferred to Leathers plant in Trafford Park.

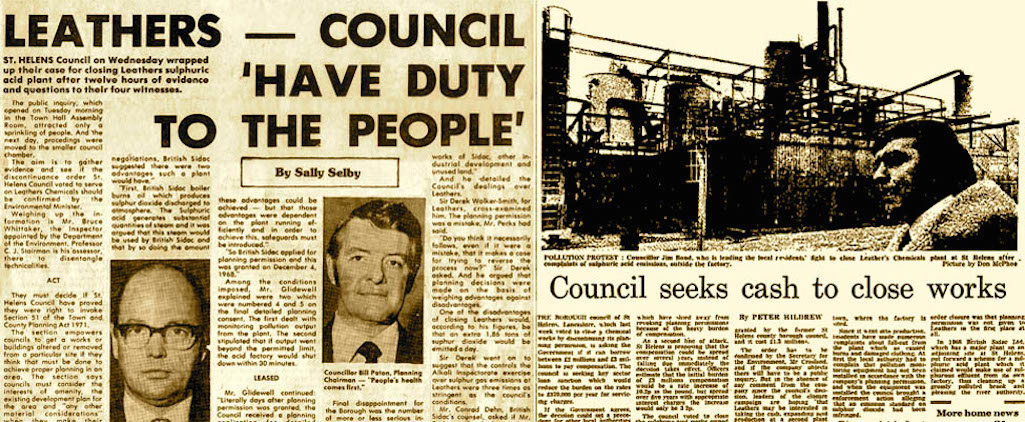

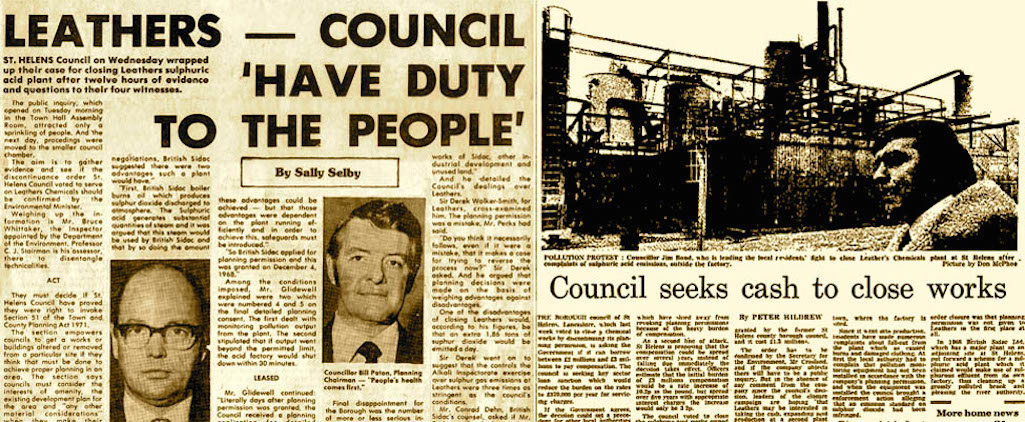

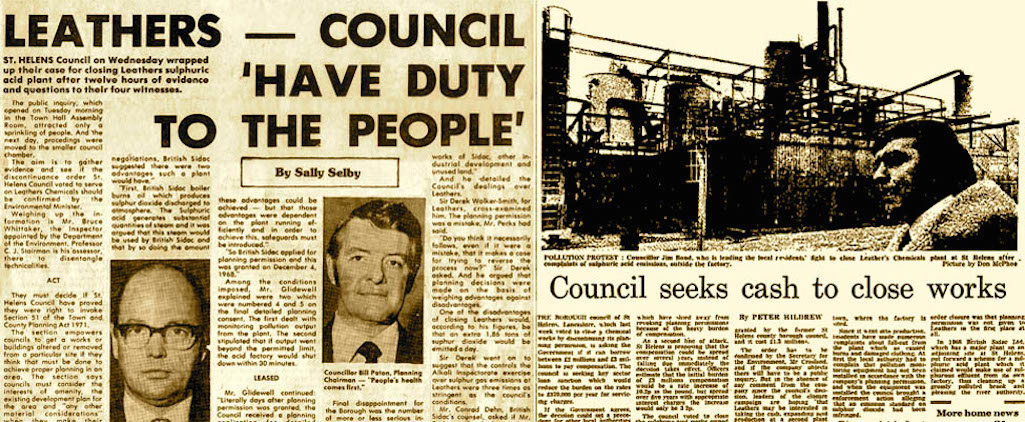

Leathers responded by extensively overhauling their Sutton plant at a cost of £340,000. This led to the works being closed for several months, only reopening in mid-November 1975. A new cooling system was installed and the height of its chimney stack was raised from 140 to 200 feet. However the council still wanted the plant closing and so Leathers appealed against the decision and a week-long public inquiry was held in January 1976. St.Helens Council produced as evidence a list of 45 pollution incidents, two of them serious. Claims were made that acid fallout had led to women's tights being destroyed, plants on allotments dying and patients in St.Helens Hospital coughing. Planning Committee Chairman Councillor Bill Paton told the inquiry: "In the Council’s view they have a duty to the people of Sutton to remove this fear from their minds and let them breathe freely once more."

How the St.Helens Reporter (left) and the Guardian newspaper covered the week-long public inquiry into Leathers

How the St.Helens Reporter and Guardian newspaper covered the inquiry

How the press covered the inquiry

So Leathers argued at the inquiry that some 'teething troubles' were inevitable. The chemical company won their appeal against the council closure plan, to the disappointment of local residents but to the relief of their workers, many of whom would have lost their jobs. However the plant remained controversial and in January 1985 the Health & Safety Executive advised St.Helens Council to shelve their plan to build housing for the elderly near to Leathers. Their confidential report stated that an accident at the chemical plant would endanger people within a one mile radius.

Ten appliances and fifty firemen quickly arrived at the scene and they sprayed the defective tank with water. Despite this a further emission of the acid gas took place at 2:50pm and it took six more hours before the situation was brought under control. The fire brigade worked through the night as Hays staff transferred the oleum into another tank.

Morrisons supermarket in Baxters Lane evacuated shoppers for the day and a major golf tournament in Sherdley Park was called off, with the players told to take cover from the deadly cloud of sulphur trioxide. Even trains on the Liverpool to Manchester line were re-routed and St.Helens Hospital sealed all doors and windows and turned off its ventilation system. Between 3pm and 7pm the hospital was on full alert for an evacuation and emergencies were diverted to Whiston Hospital. Fortunately there were only two casualties affected by the cloud, and they required reassurance rather than treatment.

Agnes Dance from Baxters Lane told the St.Helens Reporter that: “It was just as if an atomic bomb had gone off. There was a thick fog and we were all terrified.” The town’s two MPs – John Evans and Gerry Bermingham – expressed grave concern about the leak and tabled questions in the Commons. The three East Sutton ward councillors were equally concerned and said that the plant should be closed. Their call was echoed by 4,000 people, who signed a petition demanding Hays’s closure, but instead of shutting down the acid factory chose to expand.

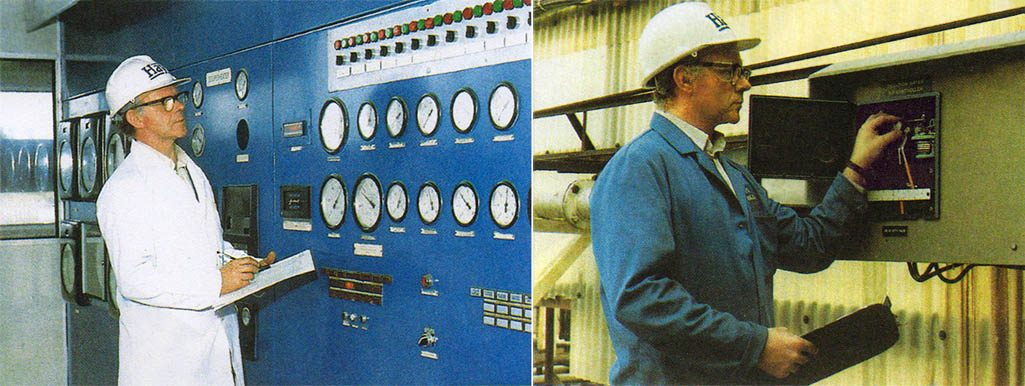

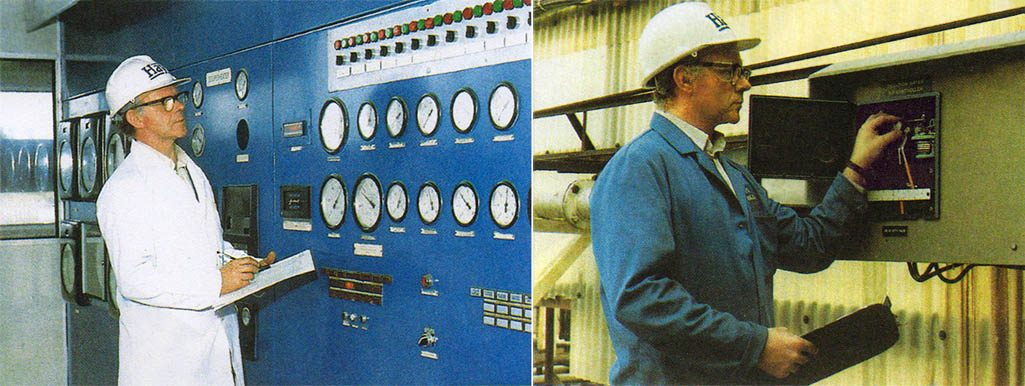

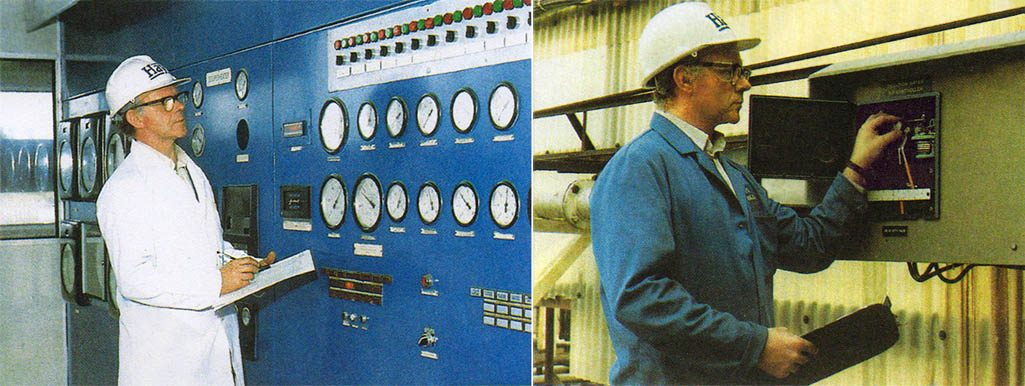

Left: The control room inside Hays Chemicals plant in Lancots Lane in Sutton; Right: A regular safety inspection

Left: The control room inside Hays Chemicals; Right: A safety inspection

Control room and safety inspection

However Hays insisted that the work was centred on improving safety at the plant and was completed in April 1987 at a cost of £150,000. Two large tanks – including the one that caused the leak – were removed and replaced by smaller tanks, which the company felt would create less risk. The 4-tank storage system was completely re-designed and several back-up systems and data recording systems were installed, allowing the temperature to be monitored constantly at 40 different points.

During the following month electronically controlled gates were installed on the site, to stop people – especially children – from wandering into the plant. The company was keen to improve its community relations and announced it was sponsoring St.Helens Amateur Rugby League and St.Helens & District Mid-Week Cricket League for a total of £6,000. In interview with the St.Helens Star newspaper on May 14th 1987, executives from Hays said the firm wanted to be good neighbours and denied that their plant was responsible for any strong smells in the Sutton district, claiming they were odour-free.

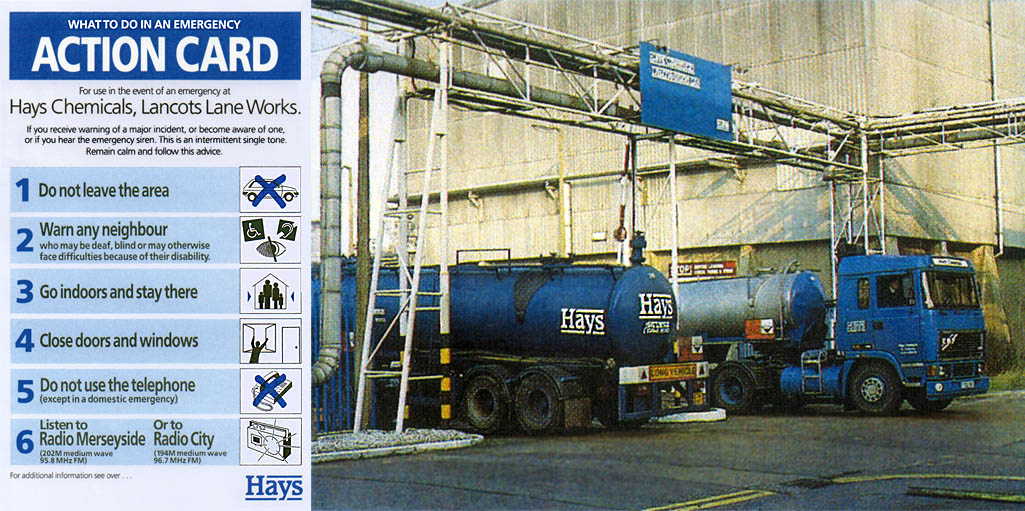

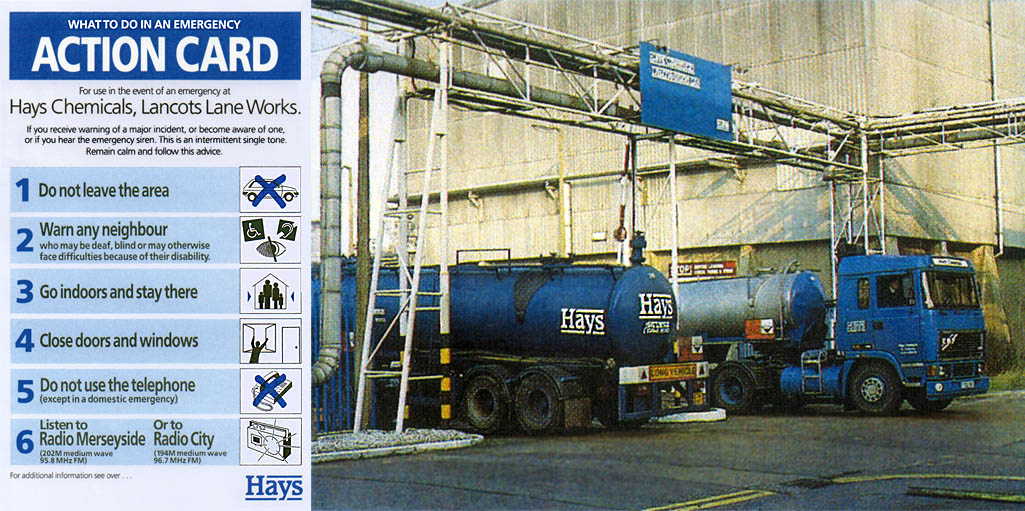

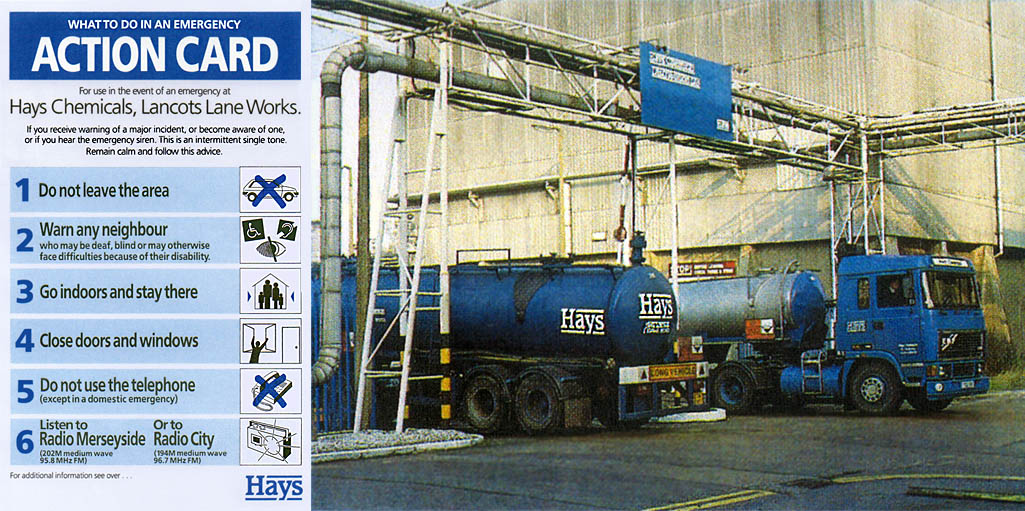

Left: Emergency action card for nearby residents; Right: Loading tankers at Hays Chemicals plant in Lancots Lane

Left: Residents’ emergency action card; Right: Loading tankers at Hays

Loading tankers at Hays Chemicals

The reassurances didn’t impress local people who complained to the St.Helens Star on May 21st. Alice Foster from Baxters Lane said: “Have they thought how frightened we are living near their time bomb?”. B.R. Hesford, also from Baxters Lane, wasn’t impressed with Hays’s claims of being odour free: “How would you describe the stench of burning sulphur and acid when you’re downwind of the place?”. Councillor Geoff Brown wrote: “Latest technology at the plant may monitor the dangers but it won’t stop them…Hays is a thorn in our side, keeping both industry and house builders away”.

During the same year Hays submitted a planning application to St.Helens Council to convert a powdered sulphur store into a sulphur grinding plant. They also wanted to build additional offices and stores at their Lancots Lane works but St.Helens Council rejected their application after a residents’ campaign. Hays appealed to the Department of the Environment and a three-day public inquiry began on January 19th 1988, in which locals expressed great concern that the new unit would exacerbate the dangers posed by the existing works. In mid-March the D. of E. Inspector, D. E. John, released his findings, which overturned the council’s rejection upon condition that the company produced detailed schemes to reduce noise and dust.

Shortly after 7pm the first of nine fire engines arrived at Hays in response to a call saying a drum of sulphur trioxide had been punctured by a forklift truck. Wearing breathing apparatus the firemen tried to damp down the imaginary fumes from the drum with sand. An equally imaginary gas cloud floated towards Morrisons in Baxters Lane but at 8:20pm it was announced that the cloud had dispersed. Hays and the emergency services declared the exercise to have been a success but Rita Atherton of the Sutton Action Committee was decidedly unimpressed: “It is ridiculous, they could be dealing with real lives and not with toys. They began nearly half an hour later than expected and if they cannot organise this, how will they deal with a real emergency?”.

Left: ‘A Closer Look’ - part of Hays information pack from 1989 of which 6,000 were sent out; Right: Invitation to a guided tour

Part of the Hays information pack that was sent out in 1989

Hays information pack from 1989

It was mainly in response to new EEC rules, known as CIMAH regulations. These obliged the firm to ensure that local residents were fully aware of what was produced and stored at their factory and the emergency arrangements that were in place in case of a major incident. The information pack included a letter from the manager, guided tour invitation and a glossy brochure called ‘The Inside Story’ that provided a closer look at the Sutton plant. This said:

Joe Marshall Manager of Hays

In 1999 a major refurbishment took place at the factory and at the end of 2001, Hays was taken over by Albion Chemicals. Six months later the company shocked their 60 workers when they announced that the plant was closing down. The closure - which took place at the end of April 2002 - was blamed on the rising costs of raw materials and the falling price of sulphuric acid, which had made the business unprofitable.

e) The Brook Blue Works of Micklehead

Brook Works (a.k.a. Brook Mills) at Micklehead Green, near Lea Green and Rainhill, manufactured ‘blue’ for over one hundred years. Their product was used when washing white fabrics to compensate for a slight colour cast and give clothes a whiter appearance. Although often referred to as ‘dolly blue’, this was in fact made by William Edge & Sons of Bolton, with the brand name copied by others.

Workers at Brook’s blue works in Micklehead Green pictured in 1889 - Photograph John Roscoe

Workers at Brook’s blue works in Micklehead Green pictured in 1889

Workers at Brook Works in Micklehead

A view of Brook Works in Micklehead Green taken from School Lane in 1912 - Photograph John Roscoe

View of Brook Works in Micklehead Green taken from School Lane in 1912

Brook Works from School Lane in 1912

Workers at Brook Works in the 1920s (n.b. background chimney is Sutton Manor Colliery) - Photograph John Roscoe

Workers at Brook Works in the 1920s (chimney is Sutton Manor Colliery)

Workers at Brook Works in the 1920s