An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 93 (of 95 parts) - History of Lea Green Colliery (1870s - 1964)

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me

Bold Colliery | Sutton Manor Colliery | Sherdley

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

The first shafts at Lea Green Colliery were sunk by James Radley in the early to mid 1870s, first appearing in the Mines Lists for 1877. However this was not the first coal mining in the district as the Eltonhead family had extracted coal as far back as the 16th century. The Ordnance Survey map of 1849 shows Elton Head Colliery adjacent to the Liverpool to Manchester railway line in Lea Green, with a number of disused coal shafts also marked. It’s quite likely that Radley’s new coal mine reused at least one of the old Elton Head shafts.

James Radley also owned Nutgrove and Thatto Heath collieries (which first appeared in the Mines Lists in 1867 and 1874 respectively), as well as the Sutton Heath Colliery. This was situated on the corner of Elton Head Road (then known as Mill Lane) and Sutton Heath Road and was first referenced in 1867. In 1873 Radley was made the fourth mayor of St.Helens and served three successive terms. In 1876 he opened the new Town Hall and presented a large gold chain of office to St.Helens Corporation, as well as a clock which was placed in the Parish Church's tower. Radley was also a benefactor of St. Johns Church, Ravenhead and his generosity is acknowledged via an inscription on a chancel screen within the church.

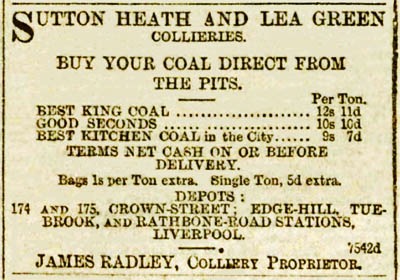

James Radley regularly advertised

His butler at Sherdley, incidentally, had been Henry Short, who later ran the Commercial Hotel in Rainhill and also catered for dinner parties and balls. Radley’s widow, Fanny Prescott Radley, ran Lea Green Colliery for a few years after her husband's death, before creating the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Co. Ltd. This was registered on June 28th 1890 and had a capital of £100,000, with the Radley family retaining a controlling interest. William Moore Campbell was appointed managing director with an initial salary of £500 per annum, plus 5% of net profits.

Dozens of men and boys lost their lives at Lea Green in a variety of different ways. In January 1886, George Parr, colliery 'hooker-on', died after being struck on the head by a bolt that was dropped down the shaft. Twelve months later 53-years-old William Lunt was instantly killed by stones from a blast after lighting a fuse. He was profoundly deaf and thought his 'shot' or blasting cartridge had already gone off and so returned to the spot prematurely. The Liverpool Mercury said Lunt's body was 'fearfully mutilated'.

On May 4th 1888, three men were killed and three others injured as a result of an explosion in Lea Green's Potato Delph mine. The dead were 26-years-old William Lunt (probably nephew of above), 49-years-old Christopher Tharratt, who took 9 months to expire, and Matthew Mercer, who died 10 months after the explosion. The injured included William's father Thomas and his brother John. The blast was caused by using naked candles down the pit as the law then only required the use of safety lamps if gas was known to be present. The colliery managers had previously been advised by Henry Hall, Inspector of Mines, to always use safety lamps but had ignored his advice.

In the twelve months ending April 1889, a total of 220,000 tons of coal were produced at Lea Green and more sidings were approved in July of that year. In September 1890, 14-years-old pony driver, Thomas Hitchen, was crushed to death as a result of driving a 'journey' of wagons too fast, something boys often did. The young lad of 680 Mill Lane, Sutton Heath, was the son of the underlooker (mine official), also called Thomas Hitchen, who ran to his son's assistance but found him dead. In April 1892, 21-years-old St.Helens rugby player James Rennie, a waggoner of 25 Chester Lane, was crushed by a large stone in Potato Delph pit and broke his back, dying one week later in hospital. Then in May 1892, 71-years-old Peter Platt was crushed to death after crossing between wagons when shunting suddenly resumed. Platt didn't apparently hear the engine driver's whistle.

The creation of the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Co. Ltd. led to new investment at Lea Green and by 1892 the sinking of the new Queen and King pits was well underway. On the surface new colliery buildings were created and the railway layout was enlarged. In 1893 contractor Isaiah Piggott was commissioned to build an upcast and downcast shaft for the King mine and on March 30th sinker George Atkinson had a dramatic escape from death. The young man had rammed four 'shots' into the solid rock at the bottom of one shaft. Atkinson lit their fuses and he and his assistant quickly climbed into a large iron bucket, known as a 'hoppet'. A signal was given to the engineman on the surface to bring the hoppet up and an acknowledgement was received. But to the men's horror, the bucket failed to budge.

They were only feet away from the shots, which were set to explode within seconds. So Atkinson leapt out of the hoppet to extinguish the fuses and managed to cut one of them. Before the chargeman could cut the others, the hoppet began to ascend and he instinctively dashed towards it, grabbing hold of an outside edge with both hands. With his body hanging down from the hoppet, Atkinson was hauled 250 feet to the surface. The three charges exploded moments after the pair had lifted off but neither men were hurt. Just what the sinker from Boundary Road in St.Helens said to the engineman isn't, however, recorded!

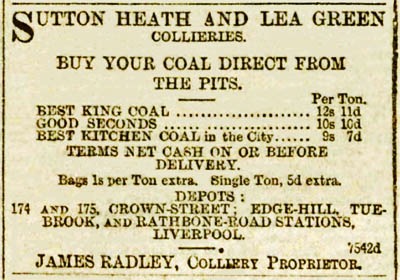

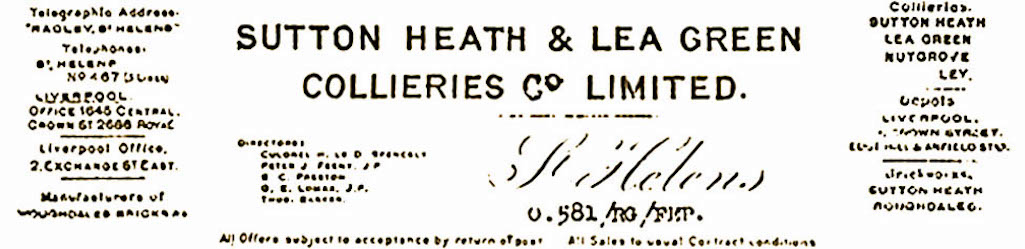

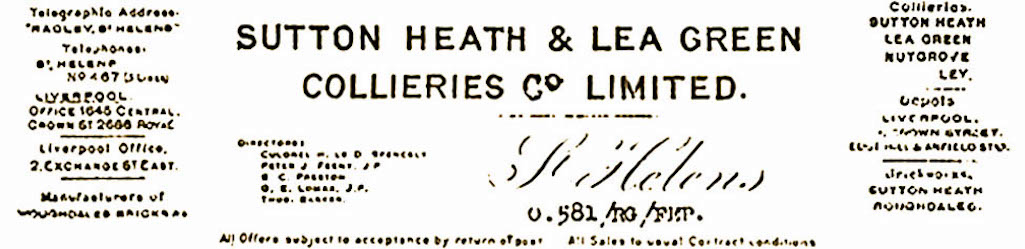

Letterhead of the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Company, which was used in an 1921 letter

Letterhead of the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Company

The letterhead of the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Company

This led to Henry Hall, Inspector of Mines, bringing proceedings against the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Co. for not having sufficient ventilation and failing to use safety lamps. Amazingly the manager at Lea Green, Thomas Pennington, claimed in court on January 8th 1894 that he was unaware that he had responsibility for shafts under construction. Sinker Richard Croan gave evidence to the six hour hearing that gas had been found in the shaft before the explosion. Asked whether the man in charge of the gang was not required to report the presence of gas, Croan replied that he would have been sacked if he had. However the prosecution failed, with the magistrates clearing the company and the manager of one charge and the second charge was withdrawn.

It was quite common for fathers and their sons to work together down the pit. In February 1894, 49-years-old Robert Hill of Cairne Street was working with his young son James in the Main Delph Mine of Lea Green when a quantity of cannel coal fell from the roof, burying him alive. Hill had been warned by fireman William Houghton to use more props but had failed to do so. In July 1894 Edward Birchall of Brown Edge was killed and his son Thomas injured by a large stone 12 feet long and 5 feet thick which detached itself from the side of their workplace.

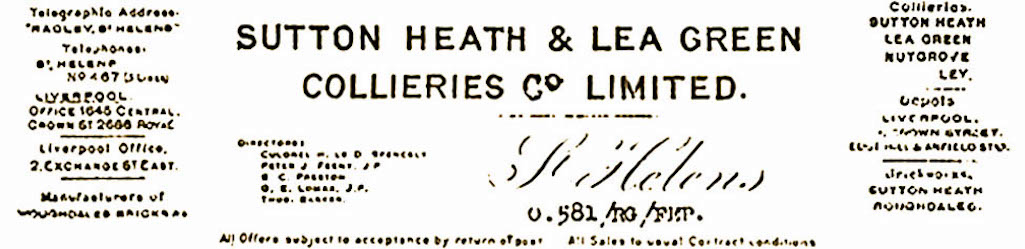

The three headgears of Lea Green Colliery in Lowfield Lane, St.Helens; L - R Old pit, King pit and Queen pit

Three headgears of Lea Green Colliery; L - R Old pit, King pit and Queen pit

Lea Green Colliery’s three headgears

In September 1895 fireman Peter Malone of Mill Lane, Sutton Heath, was killed and two men injured by a blast after fireman Timothy Foster of 32 East Street had lit a fuse without checking sufficiently for the presence of gas. Then in May 1896, William Jones slipped backwards while lifting a box onto rails and his arm became trapped. He ruptured muscles and died a week later from inflammation of the heart. The numbers of boys who were killed or injured was especially tragic. In July 1896, 16-years-old pony boy George Stott died while leading a pony that was pulling three full coal wagons. George fell and the first wagon passed over him and he was instantly killed.

On April 10th 1896, the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Co. were prosecuted for having an unjust weighing machine. The miners were paid piece-meal and so the coal coming out of Lea Green had to be weighed. Tests by Police Sergeant Kerrigan had revealed that the machine was 28 lbs. out of balance, although it was in favour of the men. Defence solicitor J. O. Swift argued that the company had only defrauded itself and so the charge was dismissed. One of the magistrates was miners' agent Thomas Glover and there was laughter in court when he quipped that there should be more machines like it.

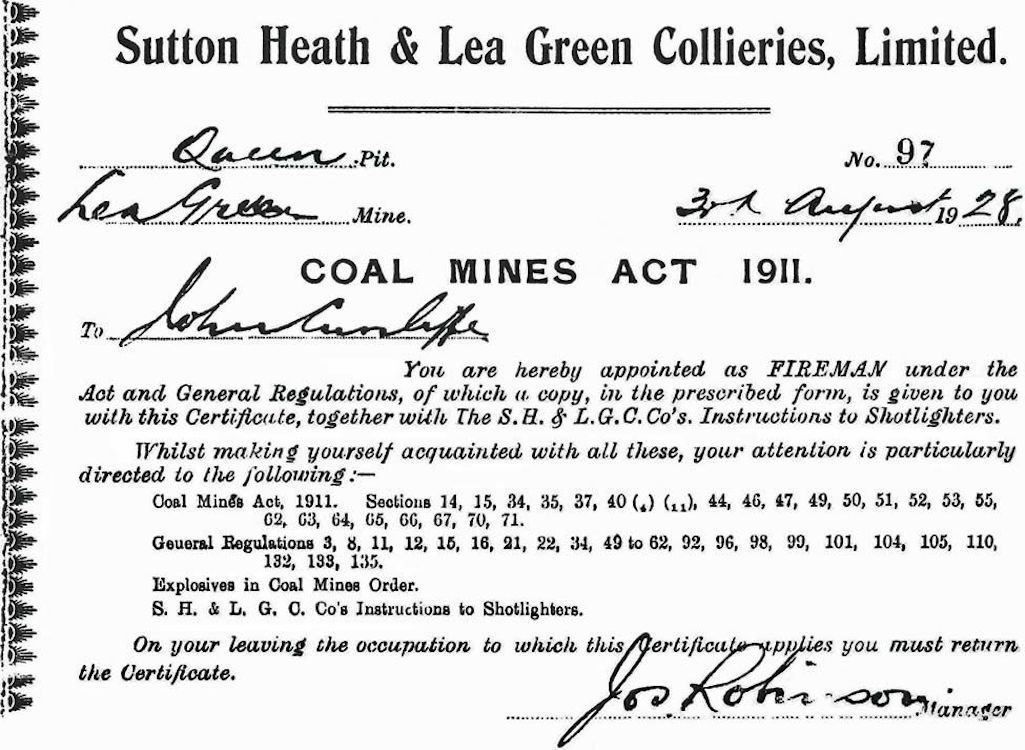

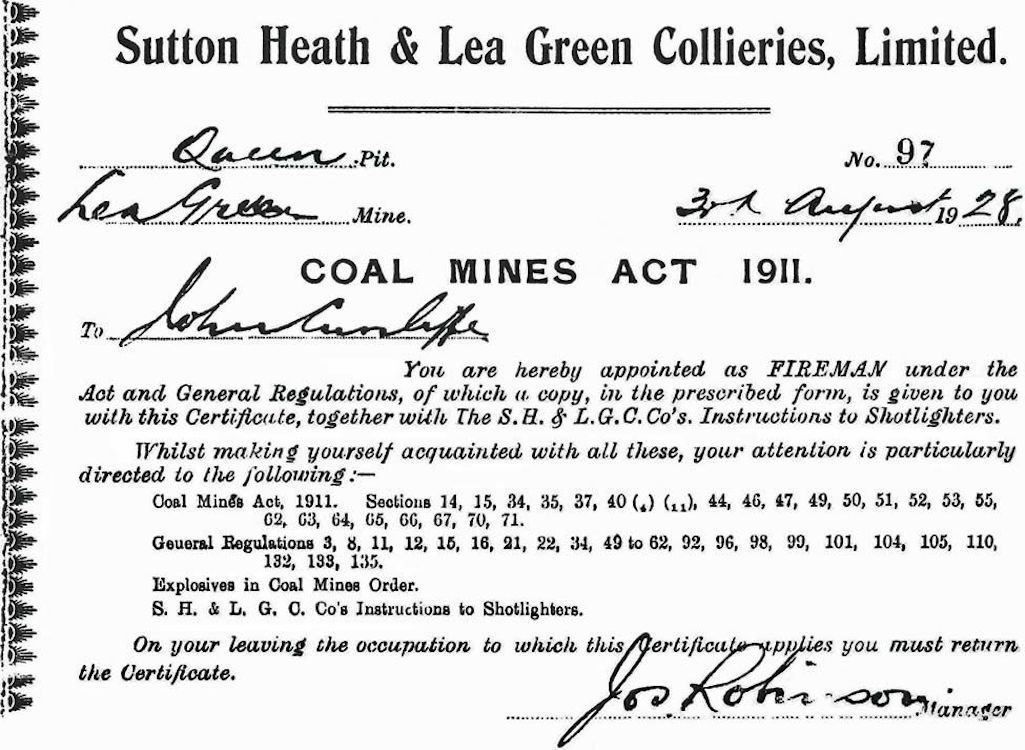

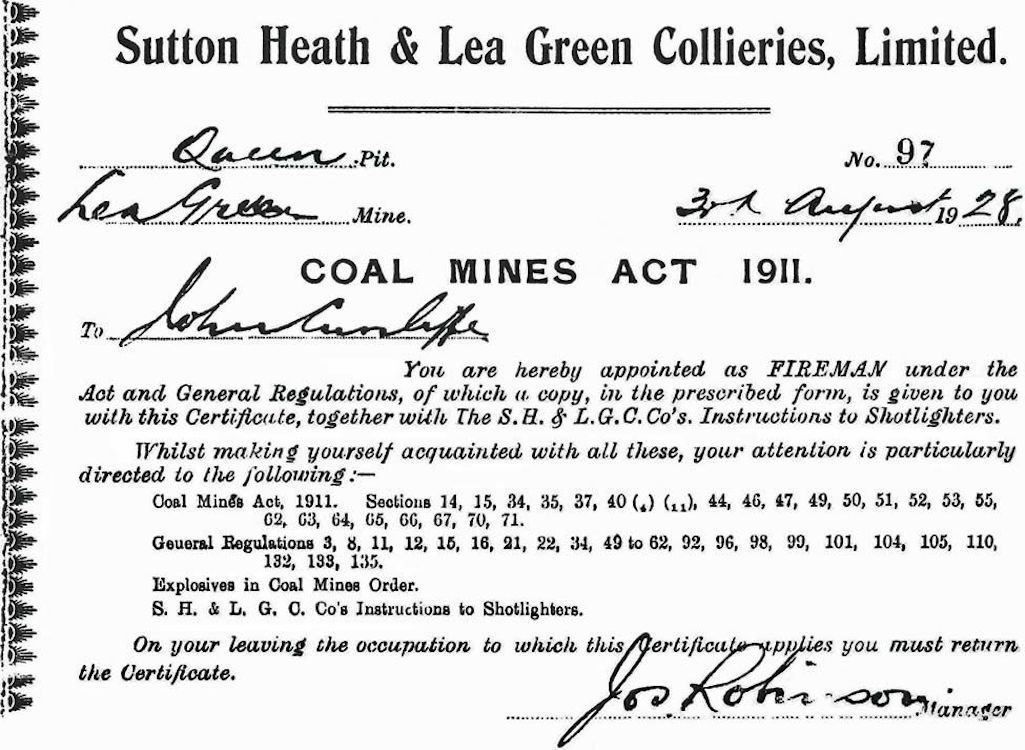

Manager Joe Robinson's signature on John Cunliffe's fireman certificate in Queen Pit at Lea Green Colliery

Manager Joe Robinson's signature on John Cunliffe's fireman certificate

John Cunliffe's fireman certificate

Roof falls were common underground, often caused by insufficient propping. In January 1897, 50-years-old Thomas Havey was buried alive at Lea Green's King pit while repairing a roof. The Liverpool Mercury wrote that '10 tons of rubbish' fell on him. Then in March 1897, Thomas Isherwood of Jubilee Cottages, Clock Face Road, was badly injured by a roof fall but took two years to die.

Two 14-years-old boys were badly injured during 1897 in separate accidents. In June 14-years-old pony boy John Herbert Gamble fell under wagons and the wheels fractured his right thigh and jaw. Then in August Joseph Brown of Ellison's Square, Thatto Heath, was knocked down by a box of coal and received a severe head wound. In February 1898, 22-years-old labourer Jesse Dingsdale fell 160 yards down the shaft and was instantly killed.

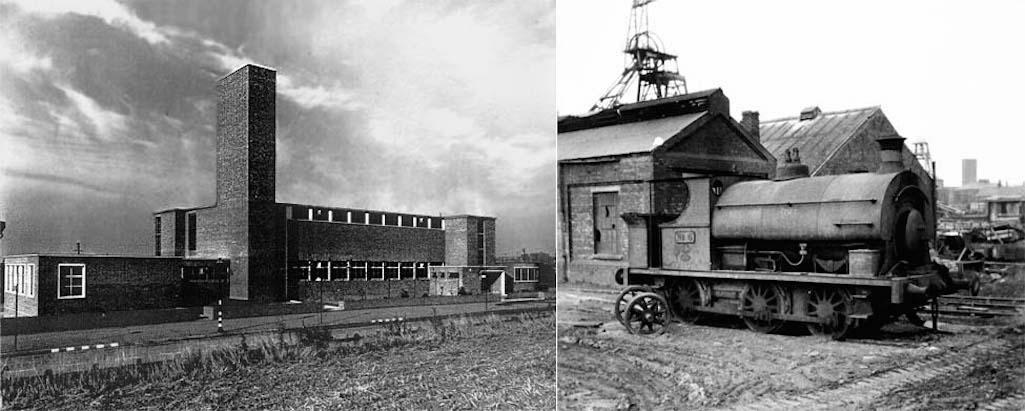

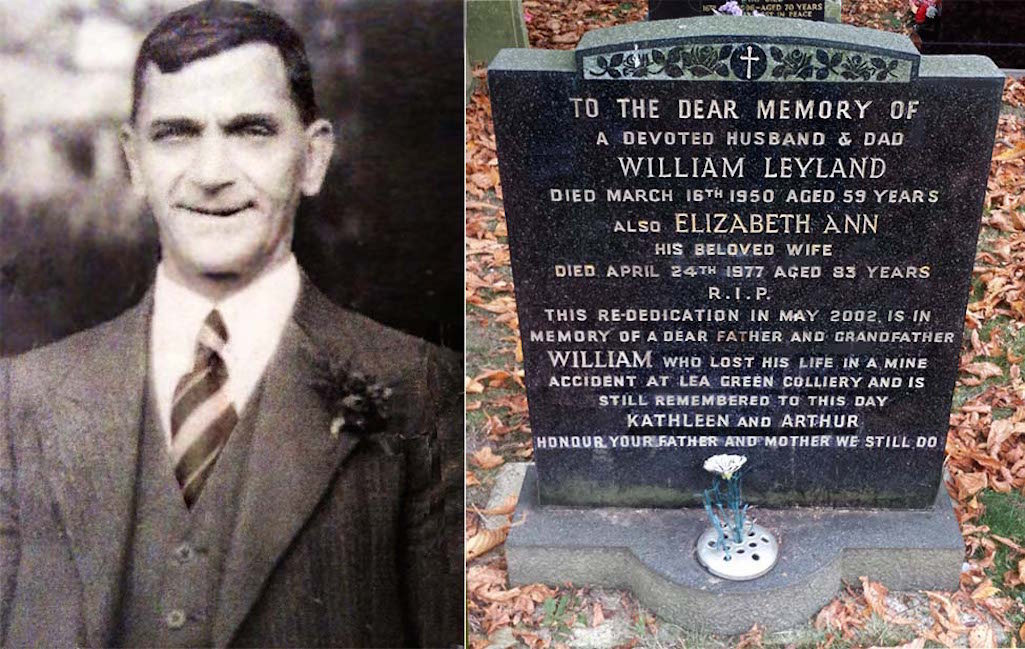

Steam locomotive 'Haig' pictured at Lea Green Colliery on June 6th 1959

Steam locomotive 'Haig' at Lea Green Colliery on June 6th 1959

Haig at Lea Green Colliery in 1959

In 1897 the Workmen's Compensation Act was introduced, updating an 1880 Act that awarded up to three years wages to workers or their families who were injured or killed through their employer's negligence. Lord Salisbury's government passed the new Act, which automatically granted damages upon application to a County Court, without the need to prove negligence. However, there were so many accidents at that time that colliery owners were concerned at their financial exposure.

In June 1900 the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Co. refused to pay a compensation award to a collier called John Moore who, during the previous February, had fractured his right foot in an accident. In court they claimed a technicality, arguing that Moore had been employed at Lea Green by a contractor and not directly by the colliery itself. They also said that he'd worked for the contractor called Hankey for less than two weeks, so didn't come under the meaning of the Workmen's Compensation Act. In fact he was injured on his first day with Hankey but had much previous experience of working at the colliery. The judge dismissed their argument and awarded Moore 13s. 6d. per week compensation.

Employing contractors was a widescale practice and simply meant that the colliery paid one individual for the work involved in extracting the coal. He was employed on piecework and would hire one or two assistants - often his own sons - to help fulfil his contract. The contractor, or hewer, usually hewed the coal from the face himself and his staff - known as drawers or waggoners - would transport the coal to the foot of the pit shaft. At each fortnightly 'reckoning', the colliery paid the contractor for the recovered coal and then he in turn paid his assistants.

One of the youngest boys to die at Lea Green Colliery was William Lea of 113 Nutgrove Road, Thatto Heath who was only 13 when killed in October 1900. The lad was regulating the running of boxes up and down the brow when he was struck by a steel rope and died of a fractured skull. William had only worked there for five weeks and had told his father that he had a "nice job". A second 13-years-old, John Thomas Roberts, was killed in November 1901 when a coal box came down a brow and struck him.

At a court case on April 7th 1902, it was revealed that there had been extensive pilfering of coal from the colliery sidings. Over £100 worth had been stolen during the previous 12 months and contractor Charles Glen was fined 20s. at St.Helens Police Court for helping himself to coal.

Steam locomotive 'King' pictured at Lea Green Colliery in 1964 with pit headgears in the background

Steam locomotive 'King' pictured at Lea Green Colliery in 1964

King at Lea Green Colliery in 1964

On May 10th 1905 the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Co. were back in St. Helens County Court fighting a compensation claim. Two months earlier Edward Stringfellow had been partly buried under a fall of coal within Lea Green’s King Pit and had injured his back and chest. The company said it was the collier’s own fault as he had disregarded the instructions of a fireman. Amazingly the company had prosecuted the injured man at St.Helens Police Court on the grounds of serious and wilful misconduct, although the magistrates had refused to convict. Now Stringfellow of 22 Silkstone Street was in the County Court, claiming 15 shillings per week compensation. The company denied liability through his alleged misconduct, which they argued was in breach of the Coal Mines Regulation Act. However the deputy-judge, Dr. A. P. Thomas, allowed the award, arguing that Stringfellow’s actions should be viewed as contributory negligence, rather than serious misconduct.

It was clearly a dangerous profession for the miners, who didn't earn very much. However the management did very nicely. When William Moore Campbell, the company's managing director of Close House in Elephant Lane, died in May 1906 at the age of 71, he left £77,163. In today's money that's over £4 million. On June 1st 1908, a cage accident left eight men injured at Lea Green Colliery, including Hugh Thomas who broke a leg. There were 16 miners who were descending the shaft when the double-decked cage violently struck scaffolding at the bottom, throwing out a number of men. Safety catches prevented their probable death by drowning. Thirty-three-years-old Henry Brown was a well known soccer player and he perished at Lea Green in October 1908 after a fall of earth.

Late in the evening of August 27th 1908, a large fire broke out in old workings at the colliery. Being 700 yards away from the pit 'eye' and 500 yards underground, the fire proved especially difficult to extinguish with water, so chemical fire extinguishers were used. Efforts continued throughout the night and by the morning the fire had been brought under control.

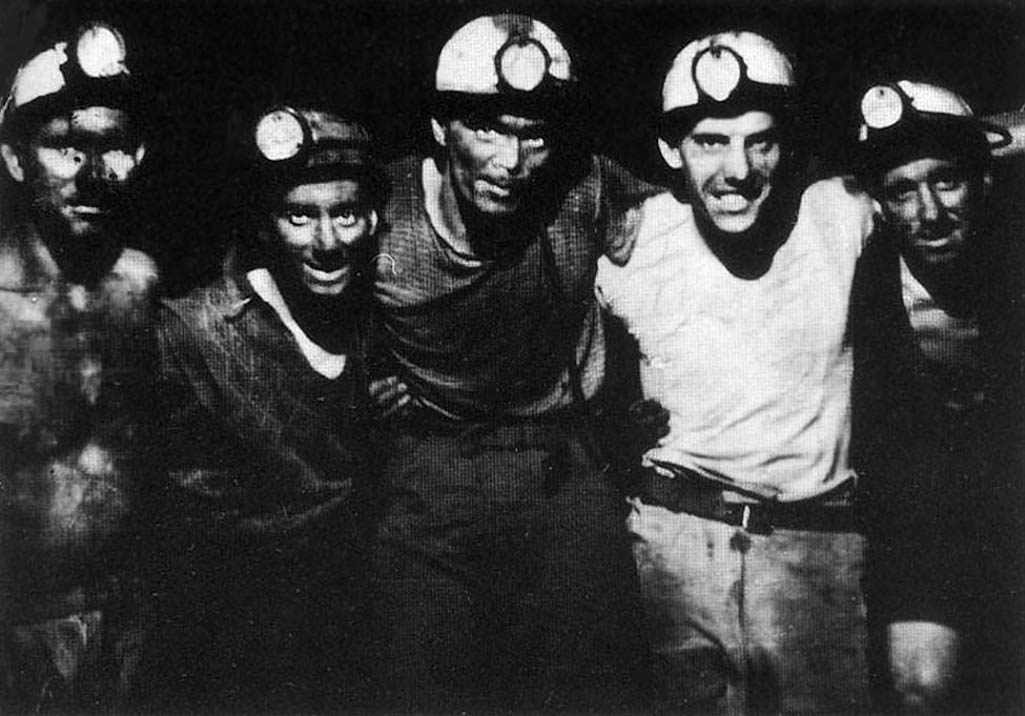

Colliers pictured inside Lea Green Colliery, St.Helens taken during the 1950s

Colliers inside Lea Green Colliery, St.Helens taken during the 1950s

Colliers down Lea Green in the 1950s

In September 1909, 50-years-old Robert Edwards died in St.Helens Hospital after another roof fall. By this time there were three pits at Lea Green colliery which were referred to as 'Old' pit, 'King' pit and 'Queen' pit. The first known death down the latter took place in June 1911 when 23-years-old Peter Robinson was killed by a large piece of rock that fell from the roof.

Also during that month three labourers, John Duffy, Joseph Armstrong and 54-years-old Stephen Kelly of 244 Clock Face Road, were killed at Queen pit when going for their dinner. They'd entered a wooden cabin at the pit top, when it toppled over and fell fifteen feet. In August 1911, 23-years-old Jane Houghton of Thatto Heath had an arm amputated after an accident at Lea Green. The 'pit brow lass' was thought to have caught her arm fast in the coal screening belt and didn't, apparently, receive any compensation.

In December 1912, contractor Thomas Regan was killed when the pit roof fell on him. A similar accident occurred in April 1913 when contractor Peter Kenny of 15 Orville Street in Sutton was killed in King pit by a large stone that fell from the roof. Thomas Green died in October 1913 when two tubs full of coal ran over him. It was thought that the 39-years-old had breached safety regulations and been riding on tubs. After falling, or being knocked off, he was then knocked down and run over.

A curious incident occurred on March 28th of 1913 when police were called to Lea Green to deal with a drunken miner at the bottom of a pit shaft. Inspector Jackson and Sergeant Heaton found Patrick Lally very drunk and refusing to go back up. After carrying him into the cage, they eventually got the burly Lally to the surface, although it took several hours. Three days later he was fined 40s. at St.Helens Police Court.

A particularly tragic event occurred on March 6th 1914 when the the body of Lea Green miner Aaron Collier was found in the St.Helens Canal. His inquest was held just hours later and a suicide note - that Aaron had left on top of a sugar basin on the breakfast table - was read out. It was addressed to his wife and said: "Dear Annie, I bid you and the children all goodbye, for I am no use in the world after what I have been through, enough of trouble with my health, and I think it is time I left this earth, so goodbye and love to all my friends, and Mr. Gordon, and Mr. Lovett". The latter were the curate and vicar, respectively, of St. Mark's church. Collier had suffered head pains as a result of an accident that had occurred when he was employed at Sutton Heath Colliery and was very depressed.

A remarkable numbers of mineworkers from the Lea Green and Sutton Heath collieries responded to the appeal for volunteers from Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War. By mid-September 1914 the miners' unions estimated that almost 500 had signed up and more would follow. With many young miners in France, older workers took on a greater role at Lea Green and a number suffered accidents. In January 1915, 63-years-old Thomas Tinlin of Heath Street died after a roof fall and in October of that year, 60-years-old William Hamilton, of 137 Watery Lane, died after suffering severe internal injuries.

In April 1916, 61-years-old Henry France suffered a brain seizure and was run over and killed by coal boxes. Henry had been a survivor of the explosion of October 1893, having been badly burnt. Then in September 1916, 55-years-old Thomas Pennington was killed by yet another roof fall. At the end of October in that year, 65-years-old James Ashton of 17 Elephant Lane fell off a scaffold and fractured his shoulder and collarbone. It was probably his son who had been killed in the colliery 12 years earlier.

Isaac Kay searched for Griffiths and in attempting to bring him to safety, was overcome by the gas and collapsed. Kay spent over an hour in the gas but was rescued by his colleagues and he recovered. Respirators had to be used to recover Griffiths' body. In October, Isaac Kay was awarded a silver medal by the Royal Humane Society and bronze medals were awarded to Ellis Jones from Marshalls Cross Road, James Ford from Victoria Street, Rainhill, Richard Davies from Cumber Lane, Whiston, Joseph Scragg from Sunbury Street and William Davies from Shaw Lane, Whiston. It was said that they had all shown 'great pluck and perseverance' in their rescue efforts. The awards were presented in St Helens Police Court on September 25th. The mine's manager James Robinson told the Bench:

However the Lea Green tram in 1918 was far more rudimentary, employing a similar system of rope haulage that transported tubs of coal. The trams were little more than a series of boxes on rails. Each tram accommodated four men and a dozen of them were hooked up together. The Government Inspector of Mines told the inquest that the tramcars had come off the rails as a consequence of coal having fallen onto them. This, he said, was something that could not be avoided in a colliery. John Macdonald fractured his spine in the accident and later died in St Helens Hospital.

On July 26th 1918 Daniel Fairhurst from Sutton Heath Road was prosecuted for firing a "shot" (explosive) at Lea Green Colliery without checking for gas. The result had been a much larger explosion than had been bargained for as a quantity of gas had ignited. The explosion did not cause any injuries but it had created "considerable alarm".

It was also an exercise in bad timing as His Majesty's Inspector of Mines was paying the colliery a visit at the time of the bang. Fairhurst's excuse was that he had been unable to examine high up in the mine, where the gas was likely to have accumulated. However it was pointed out in court that a platform could have been built and he was obliged to only fire a shot unless certain that the place was free of gas. The Bench told Fairhurst that they would only fine him £1 in consideration of his 30 years of service with the company.

On October 21st 1918 John Evans of Emily Street in Nutgrove was prosecuted after being injured down Lea Green Colliery. The 17-year-old was charged in St Helens Police Court with breaching safety rules by travelling on a haulage road underground while haulage was in motion. Although some miners used trams to get to their place of work, most men would walk. However they were forbidden from travelling when full or empty coal tubs were being transported.

At Lea Green a bell called a "cobbler" was sounded twelve times to indicate when it was safe to travel. John Evans heard a bell that he thought was the cobbler ring eight times. The lad had to walk 1,200 yards in ten minutes to get to his workplace and so he and a large number of others started to sprint up the brow. After just 30 yards the haulage rope got into motion and Evans was struck by one of the tubs and thrown to the ground. Despite being injured he was the only person who was taken to court by the company as a "deterrent not only to the defendant, but others". He was fined £5.

Robert Roberts of Dorothy Street in Thatto Heath was killed on January 26th 1919 down the King pit. He was carrying out roofing work with his brother Richard when a large stone knocked down a supporting bar and struck him and fireman Alfred Gilling. The latter – from Gertrude Street in Thatto Heath – was hospitalised but not seriously hurt.

Late on March 17th 1919 there was a fire in the fan house at Lea Green Colliery and St.Helens Fire Brigade was summoned. Water was sourced from the adjacent reservoir and the flames were soon extinguished. A fan that ventilated one of the pits was destroyed but a reserve fan was brought into service and so production was unaffected.

On October 1st 1919 Thomas Kilgallon was undertaking roofing work with his son James down Lea Green Colliery’s Queen pit, when a large stone fell onto his back, pinning him to the ground. The 47-year-old from Waterloo Street asked his 18-year-old son to remove the stone but it was too heavy for him. James called for help and it took five men to lift the stone off Thomas’s back. He was then placed on a stretcher and removed to hospital but found to be dead on arrival.

In April 1920 it was decided to reconstruct the parent company, so Sutton Heath & Lea Green Collieries Company Ltd. was wound up and replaced with a new company with an almost identical name, Sutton Heath & Lea Green Company Ltd. In their prospectus it was stated that the firm's average profit during the past seven years had been £89,309 p.a., about £2 million in today's money. As well as owning Lea Green, Sutton Heath and Sherdley collieries, the company also held £90,000 in shares in Sutton Manor Collieries Ltd. Profitable brickworks at Roughdales and Sutton Heath boosted their balance sheet.

Their pits produced a combined 600,000 tons of coal per year and prior to the war years, their brickworks were generating 14.7m bricks per annum, with the intention of raising output to 25 million bricks p.a. Lea Green Colliery was the company's most important asset, possessing three of their five winding shafts. Mining valuers A. H. Leech of Wigan estimated that the company's pits had a life expectancy of 42½ years, which was a pretty accurate prediction for Lea Green.

On January 4th 1926 Fred Hoyt – whose job was to run tubs in and out of pit cages at the bottom of the shaft – had a remarkable escape from death at Lea Green. The young man, who lived in Derby Cottages, Rainhill, was in the cage removing a box when the cage suddenly started to ascend. Not being fastened for the journey, the cage began swinging violently and repeatedly struck the walls of the shaft, with the subsequent friction causing sparks and flames. Hoyt was hurled from side to side and when about halfway up the shaft, the cage struck the other cage travelling downwards and he was thrown out.

Young Fred had the presence of mind to grip first the bell wire and then one of four guide rods that were set at each corner of the shaft in order to steady the cage. Clinging to the rod with his hands and gripping it with his legs, Hoyt slowly slid down until he was back at the shaft bottom. “It was a miracle”, he told a journalist from his hospital bed, where he’d been taken after being found unconscious.

On April 20th 1926 Hugh Twist of Cairne Street in Sutton was injured at Lea Green Colliery after been caught on a broken prop. Then in May of that year 22-years-old Robert Prescott died at Lea Green after his head was crushed between a haulage rope and a wheel. A further death occurred in March 1928 when 62-years-old Lewis C. Green was crushed between wagons.

In Charles Forman's Industrial Town - Self Portrait of St Helens in the 1920s, a former miner recalled what life was like at Lea Green Colliery. He described how those seeking work had to line up for the manager and doff their caps. Woe betided those who failed to remove them! Another miner who had also worked at Ravenhead colliery commented how conditions were better at Lea Green because their miners 'used to make a din about everything'. They were even paid a shilling a day extra when having to work underground in wet conditions. An unnamed 'pit brow lass', who cleaned the coal of dirt, described to Forman how Lea Green employed five belts. One sorted the coal from King pit, another from the Queen pit (which she said had been the best coal), one from the old pit and the fourth was called 'normal'. The fifth belt was used for the slack that had been sieved out.

On April 8th 1931 promising rugby league player Robert Smith was killed by a runaway box of coal down Lea Green Colliery. The 23-year-old from Fir Street, Thatto Heath, played for Pemberton club Wigan Highfield. Although an 'A' team player, he was well thought of and on the brink of making it into the first team. After Smith had left for work for the final time, a telegram arrived at his home to inform him that he was first reserve for Wigan Highfield's senior team game again Oldham on the following Saturday. A different type of tragedy occurred on a late Spring day in 1932 when 31-year-old Ralph Barber of Tennyson Street, Sutton Manor and 16-year-old Joseph Stanley from Chester Lane both drowned in one of Lea Green Colliery's reservoirs. You can read full details here.

During February 1932 the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Co. placed a contract with colliery engineers Simon-Carves Ltd. of Cheadle Heath for a new 80-ton-per-hour coal washery. During the depression years of the 1930s, the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Co.'s profits suffered, making only £13,574 in the year ending March 31st 1933. For most of the decade profits averaged about £35,000, which was much less than during the war years and the 1920s.

Perhaps it was for reasons of economy that in December 1935 the firm closed its four Liverpool depots and transferred its head office to Roughdales. In June 1939 the directors of the company recommended a dividend payment of 3 per cent on its ordinary shares, its first for 12 years. Improved selling prices for coal, through the operation of a Central Selling scheme, was mainly responsible for the company’s better fortune.

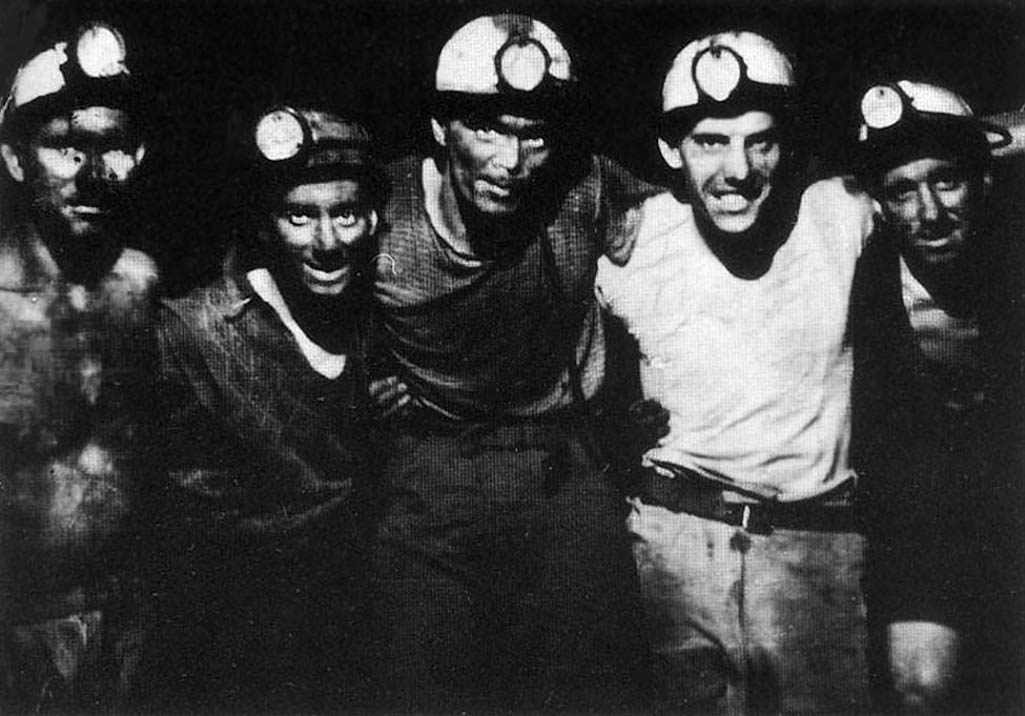

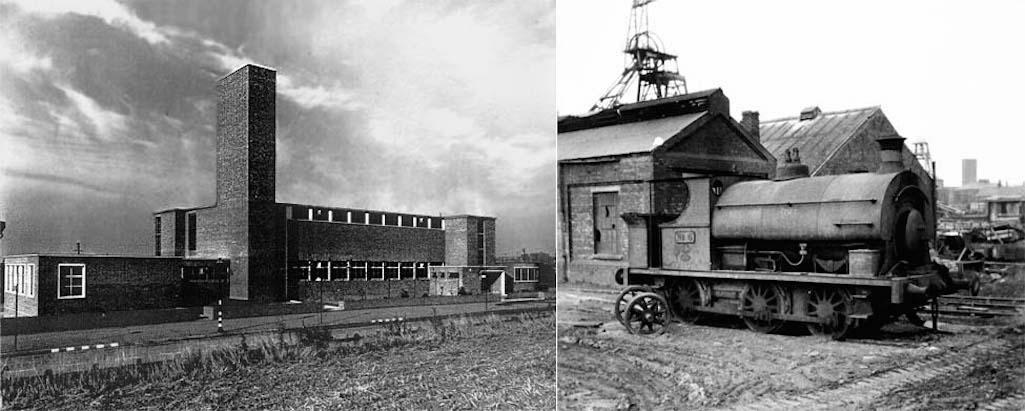

The Lea Green Colliery Pithead Baths clean entrance, locker room and water storage tower

Colliery pithead baths clean entrance, locker room and water storage tower

The Lea Green Colliery pithead baths

In the early hours of May 27th 1939, a large stone fell without warning from the roof of the Yard mine grazing the back of James Hill and pinning Richard Clayton to the ground. This caused the 53-year-old from Freda Avenue in Sutton serious injuries from which he died in St.Helens Hospital on the following day. A similar accident occurred on August 3rd of that year in Queen Pit when a stone measuring 5 ft. by 1ft. 8 inches crushed 60-year-old James (or John) Conlon of Raglan Street. It was stated at his inquest that although there were two props under the stone, a beam placed across the roof would likely have prevented the tragedy. On December 27th 1939 59-year-old Arthur Parr from Nutgrove Road collapsed and died while working as a surface hand at the colliery.

At the inquest on Charles Garner on February 22nd 1940, it was revealed that a new safety device was going to be introduced to prevent such an accident happening again. The 38-year-old from Griffin Street in Sutton had died in hospital six days after being struck by a flying handle while working in the King pit. The accident took place while he was repairing a broken belt and a brake would now be fitted to prevent a repeat occurrence.

During the bad winter of 1940 Lea Green miners tunnelled deep through snow to rescue the passengers of a train who were buried deep in a snowdrift. On July 1st 1941 ‘bogy’ trucks carrying a number of men at the colliery ran backwards, leading to twenty of them having to be treated for minor injuries.

The Daily Mirror reported on July 11th 1942 how clerks at Lea Green and Sutton Heath collieries were refusing to work overtime to implement a new miners’ pay award. They were annoyed at not being included in the wage increase, so wouldn’t calculate the men’s back pay. An official of the Colliery Officials’ Association pleaded with them to complete their work but they refused. During the following month on August 29th, haulage hand John Fenney of Clock Face Road died in St.Helens Hospital from injuries received at Lea Green three days earlier.

In January 1943 the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Co. decided to close Sherdley Colliery and transfer their workers to Queen pit at Lea Green. This was enormously unpopular with the men, who were convinced that there was much life left in their pit. The war-time fuel shortages meant it would be unpatriotic for the Sherdley miners to make a stand, so they reluctantly accepted the advice of their agent Edwin (Teddy) Hall and agreed to make the move. However their resentment continued for some time after arriving at Lea Green, which made industrial relations difficult. The transfer began on February 8th and took place in batches over several months. It involved a total of 500 miners, as well as a number of women and girls who worked on the screens.

On August 23rd 1943 eight young mineworkers at Lea Green Colliery appeared in court charged with a range of offences, mainly connected with not observing safety regulations underground. Albert Parry of Sutton Heath Road was also charged with behaving in a violent manner in a mine. The problems started when Parry refused to work on a haulage job, from which two men were absent sick. So the 21-year-old walked off and seven other haulage hands left with him. These included Wilf Etchells of Tennyson Street, John Fay and John Prescott, both of Sandon Street, and Fred Conway of Gladstone Street. Instead of walking on the proper travelling road, the group used the motion brow, and when fireman Ned Brown ordered them back, Parry was alleged to have knocked him down.

In court the colliery company described the men’s actions as anarchy, although Parry denied striking the fireman. The magistrates fined all the men £3 each and a guinea costs for breach of the travelling regulations, but dismissed the violent behaviour charge against Parry. Three of the men said they could not pay their fine and would take the alternative of 28 days. The clerk told them to think it over and said they would be given time to pay.

There are few reports of accidents during this period, although on March 16th 1943 sixteen-year-old machine attendant William Hayes of Sutton Heath Road was killed in the King pit. Then on March 21st Thomas Taylor, a 46-year-old colliery contractor from Longton’s Lane in Rainhill, died as a result of a stone falling from the pit roof.

A further fatal accident occurred on July 7th 1944 when Henry Topping was killed at Lea Green after riding on a truck down the pit, which was contrary to regulations. Coroner Bolton said at Topping’s inquest: “It is a most unfortunate accident which should never have occurred. It seems a case of familiarity with danger breeds contempt.” Industrial action did briefly take place at Lea Green Colliery during the war years. However it was over pay and took place at the end of January 1944, as part of a wider dispute in the Lancashire coalfield.

Another unusual court case took place on May 12th 1944 when three Lea Green Colliery haulage hands were accused of interfering with King Pit’s signalling system. It was revealed that on April 15th someone had deliberately short-circuited the bell signalling service, causing the ‘Stop’ bells to ring continuously. Forty-three men were unable to work for two hours and 50 tons of coal was lost. On the Saturday night it was alleged that 17-year-old Robert Twist had said to a youth named Birkett: “How did you like our bit of sabotage?” He then went on to explain how they had fastened wires to the signalling bells and hid the joins. Twist was fined £10, as were co-conspirators John Gallagher (19) of Sandon Street and Harry Johnson (17) of Oppenheim Avenue.

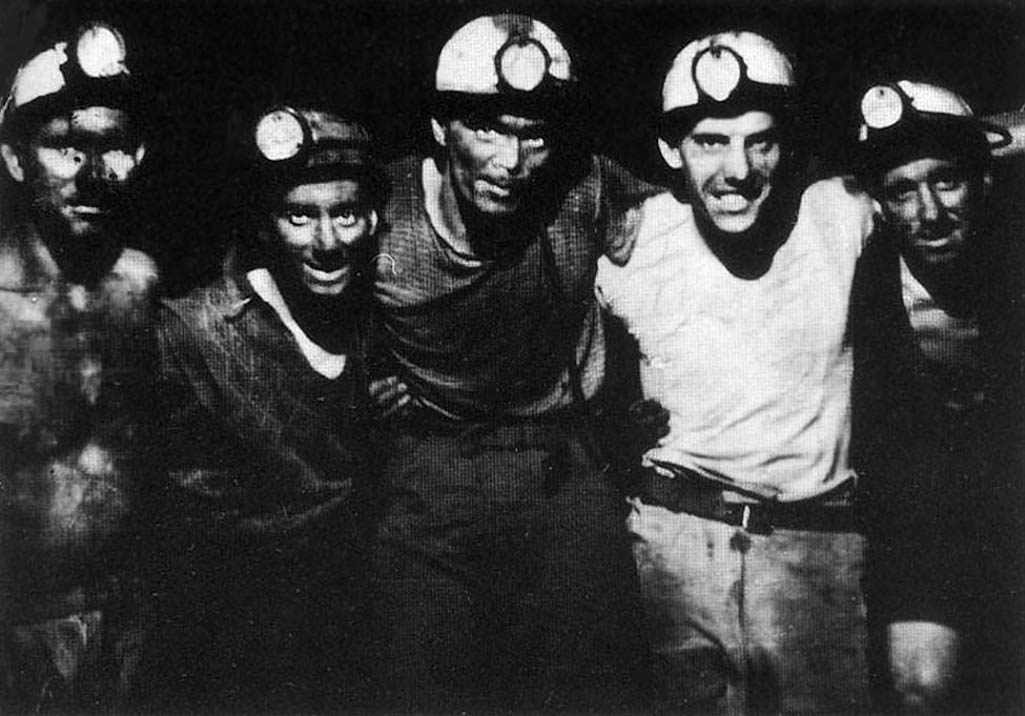

Left: Another view of the pithead baths and canteen; Right: Loco 'No 6' at Lea Green Colliery in 1962

Left: Pithead baths and canteen; Right: Loco 'No 6' at Lea Green in 1962

Loco 'No 6' at Lea Green in 1962

Robinson was succeeded as manager by Mr. Grimes, who worked until his retirement and then he was replaced by Mr. McCracken, who transferred from Sutton Manor Colliery. As well as an overall manager, each pit had an undermanager. During this period, Dan Bradbury ran King pit and the aforementioned A. E. Taylor, and then Harry Foxley, were responsible for Queen pit. There was also Percy Hughes, who was tragically killed in a mining accident.

On July 7th 1944, 30-year-old Henry Topping from Seath Avenue in Parr was fatally injured after breaking regulations and riding down the pit on the coal boxes. On January 3rd 1945 a serious fire broke out underground at Lea Green in the Little Delph mine. This was a ‘dead' mine, where coal had long stopped being extracted. The area was initially sealed off with sandbags and specially-equipped teams worked 1½ miles underground to extinguish the blaze. It took five days before mining operations in an adjacent district could resume.

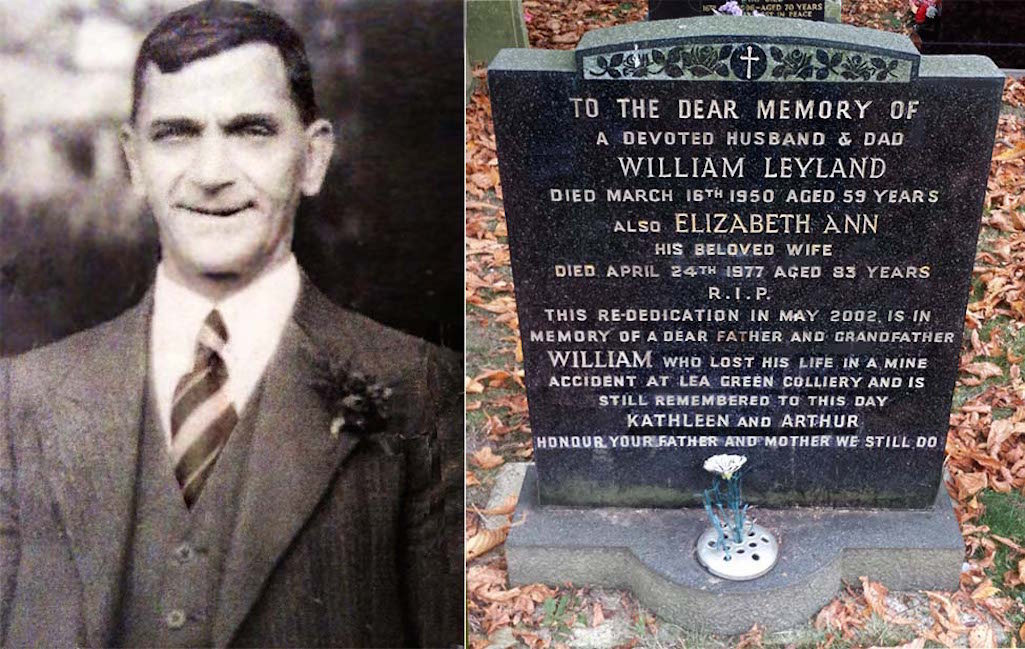

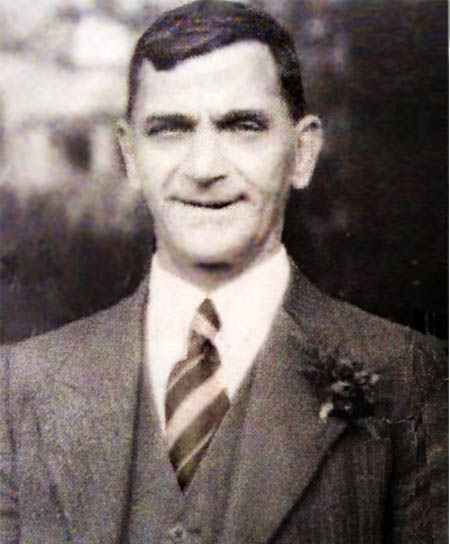

William Leyland was killed by a massive roof fall in Lea Green Colliery - Contributed by Mike Molloy

William Leyland was killed by a massive roof fall in Lea Green Colliery

William Leyland was killed by a roof fall

Suddenly a splintering of the timber props was heard and between 200 to 300 tons of dirt collapsed from the roof. Leyland took the full force and although rescuers were quickly on the scene, it took until the following morning before his body could be recovered. Miners’ agent Charles Tyrer told the inquest at St Helens Town Hall that this was a case where Mother Nature had defeated experienced men. Other witnesses confirmed that everything had been done that could have been done and no blame was attached to the men or the colliery company.

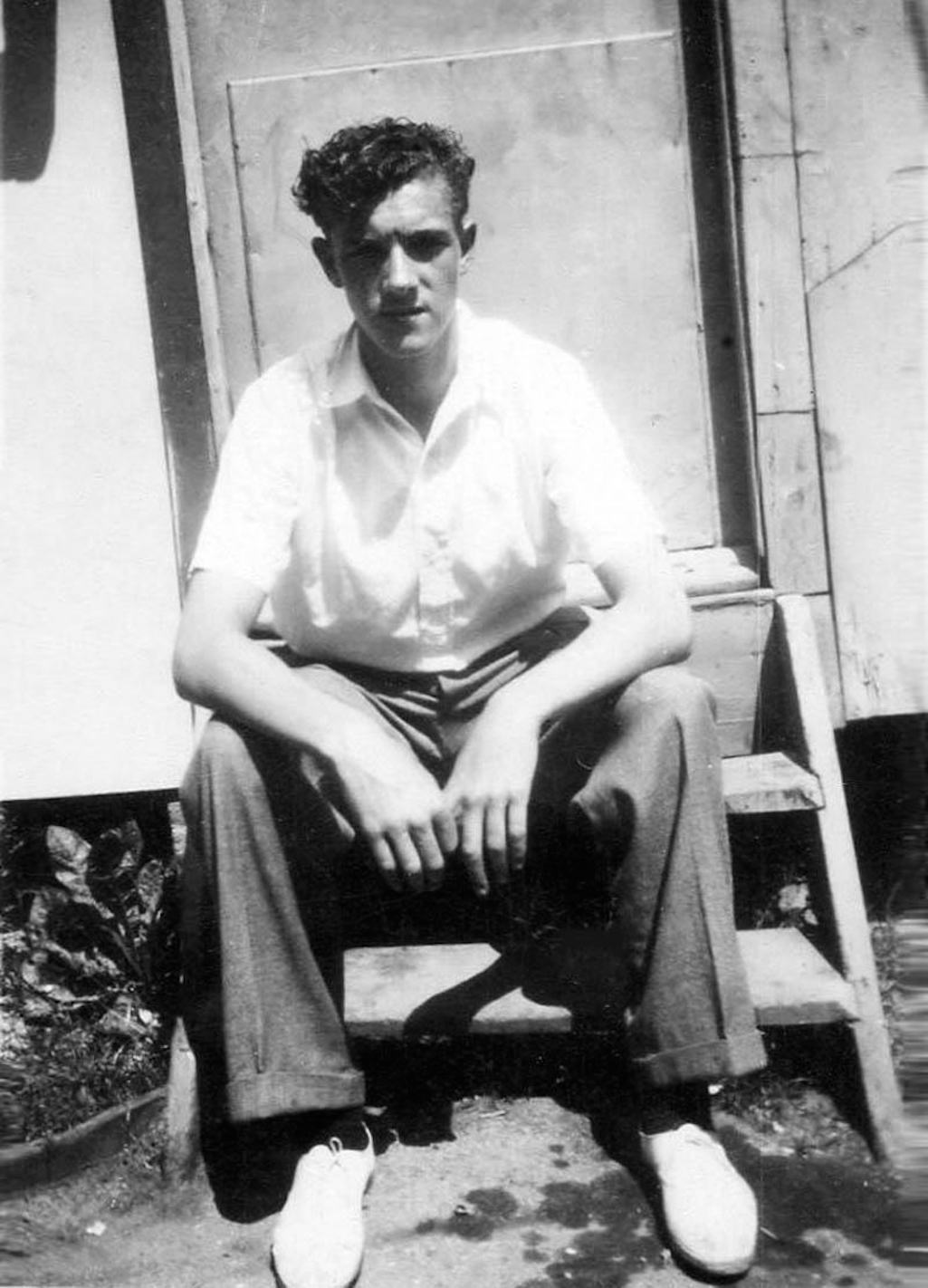

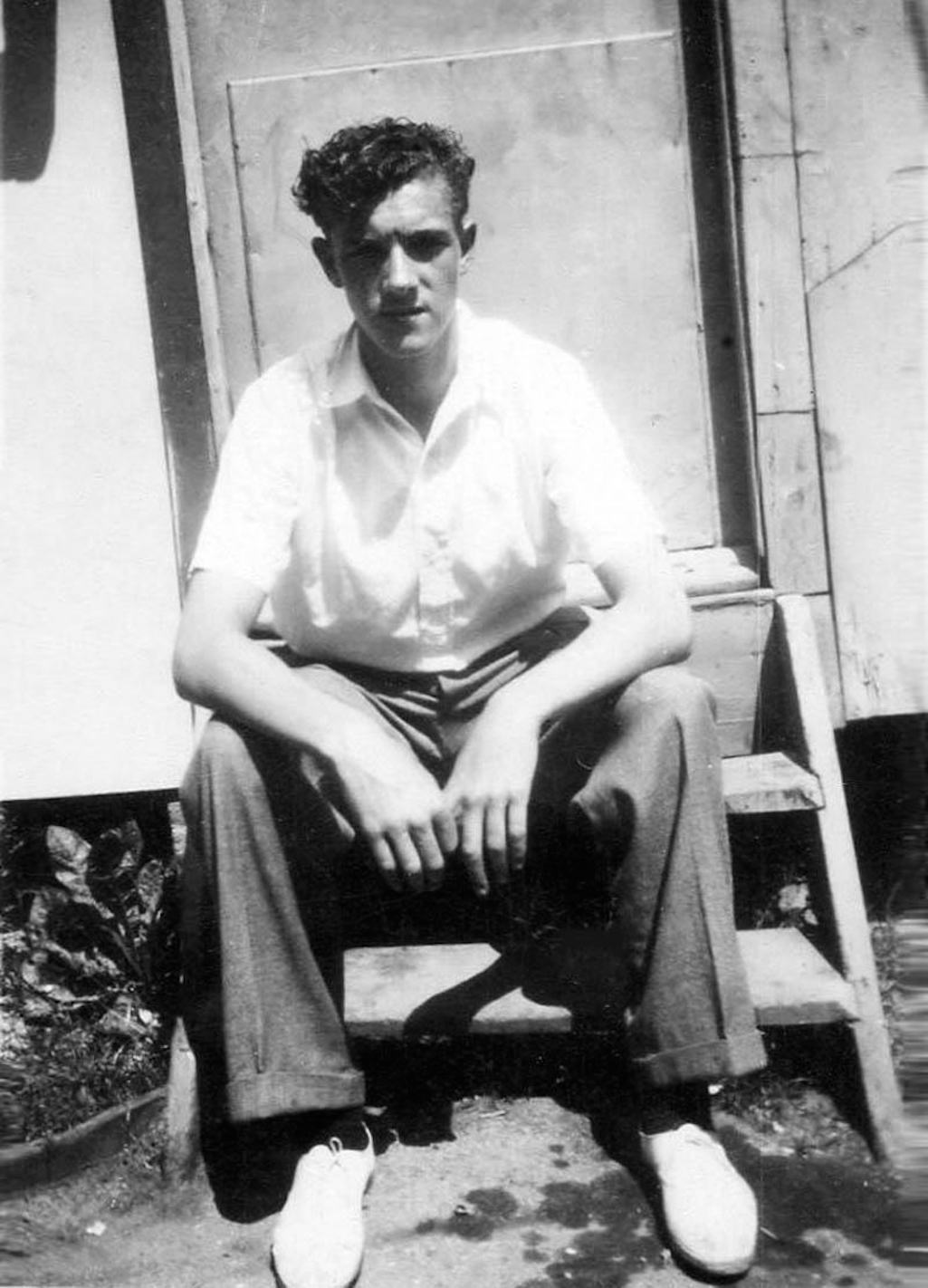

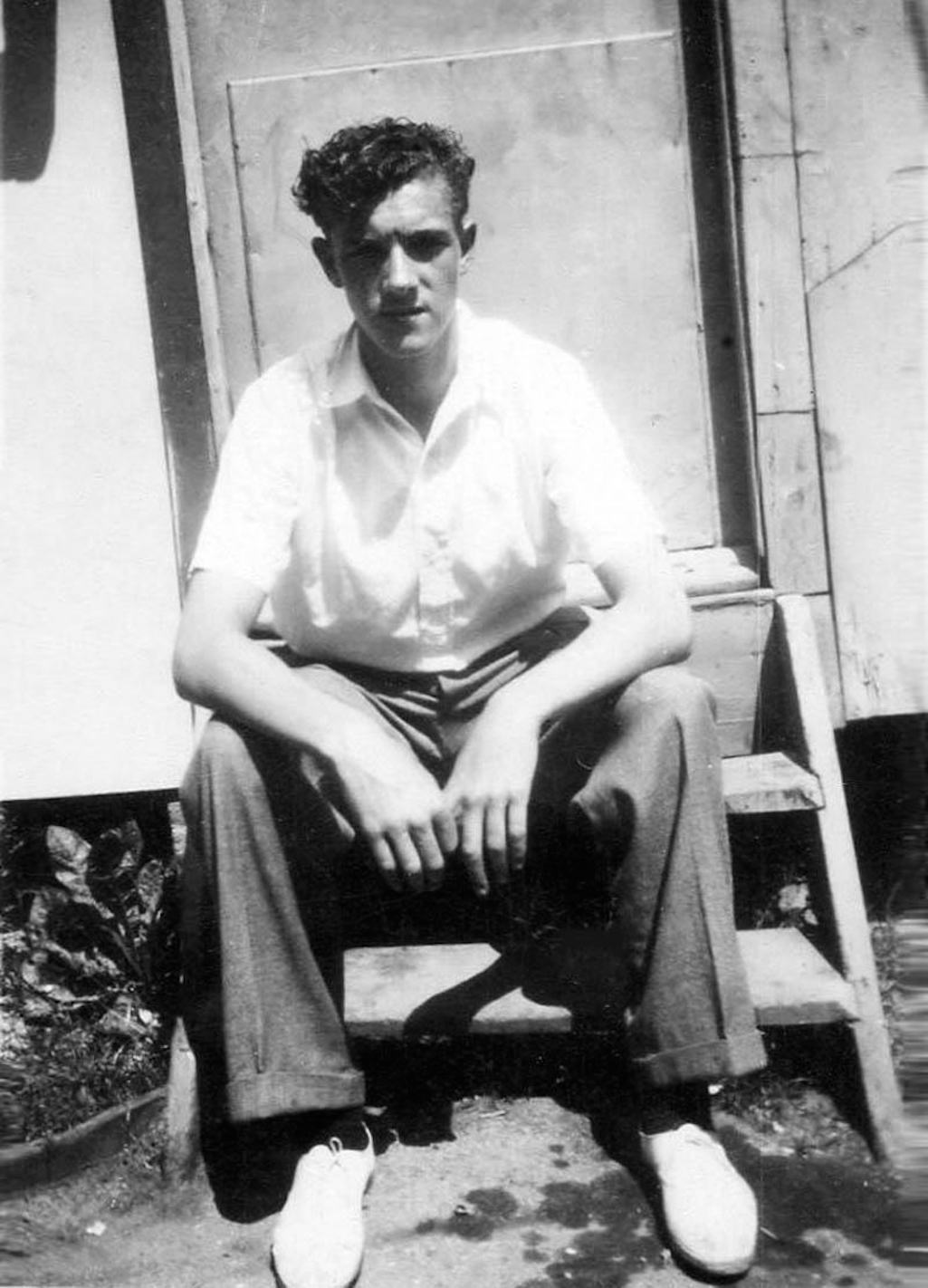

Lea Green miner and Manchester United player Bill Foulkes on the Isle of Man - Contributed by Tom Griffin

Lea Green miner & Manchester United player Bill Foulkes on the Isle of Man

Lea Green Colliery miner and Manchester United player Bill Foulkes

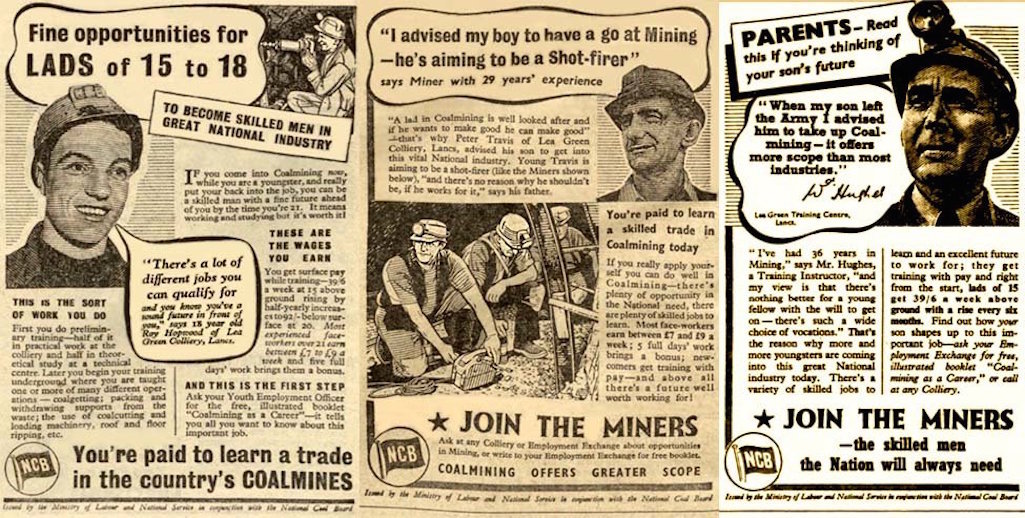

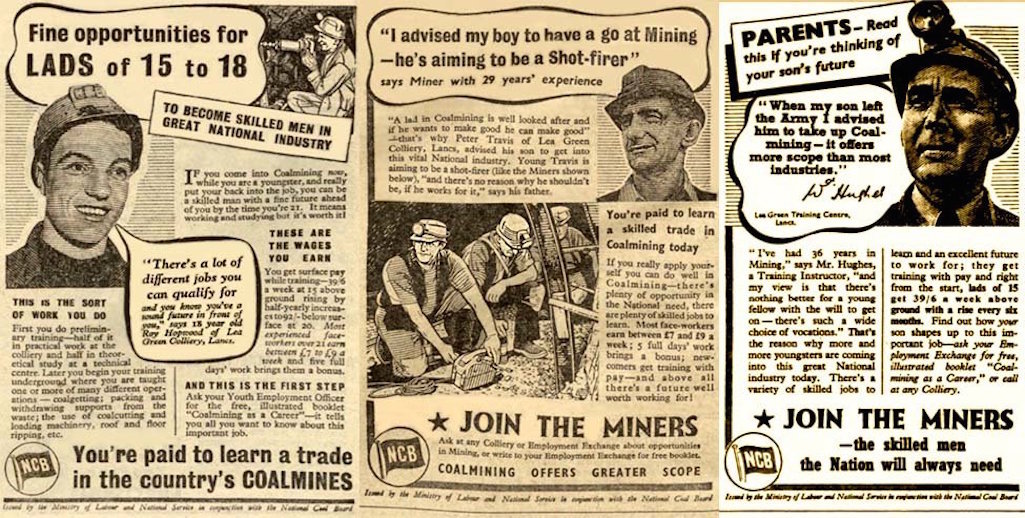

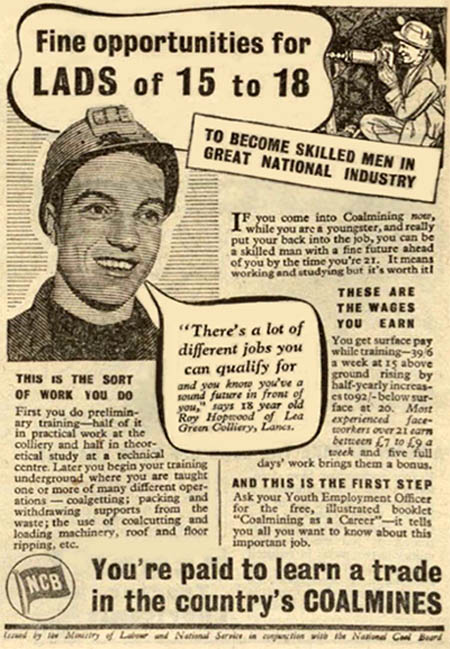

After WW2 there was a shortage of manpower in the pits, partly because the war-time 'Bevin boys' were returning to normal life. A particular emphasis was placed on recruiting school-leavers for a career in the mines. These were seen as a better long-term investment than employing inexperienced adults who might soon quit for other jobs. So Lea Green Colliery created a training centre for juveniles in their 'old pit’ 400 feet below ground. It was in a part of the mine that hadn’t been worked for 40 years and there the boys learnt face work and haulage. The Manchester Guardian of September 10th 1948 described the centre as a well-lit place which was a ‘model of efficiency in which diminutive lads with treble voices display a good deal of enthusiasm’.

The boys ranged from 15½ to 17½ years and they each spent 16 weeks training at the centre and at St.Helens Technical College. The lads at the latter studied coal mining and stripped down colliery machinery. They also worked out in the gymnasium in order to develop the muscles that would be most useful for them in their work. After graduating from the centre, they would be dispersed to one of 10 pits in the area. Mineworkers who wanted to work on the coal face could also make use of the old pit. They would team up with an experienced face worker who would show him the ropes. After the training was completed, the miner could progress to Queen or King pit and earn more money.

During 1949 adverts featuring Lea Green staff were placed in many newspapers by the Ministry of Labour and National Service

Recruitment advertisements from 1949 featuring Lea Green miners

1949 recruitment advert featuring Roy Hopwood of Lea Green Colliery

On November 25th 1950 the colliery had a special visitor when Philip Noel-Baker, Minister for Fuel and Power, made an underground tour. He told the press that unless more coal was extracted 'the situation of the country will be very serious in the early future.' Noel-Baker was a quite remarkable man who’d won a silver medal at the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp. A renowned campaigner for disarmament, nine years after inspecting Lea Green, the politician, diplomat and academic was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

On September 16th 1951 several hundred piecework men at Lea Green returned to normal working after settling a dispute. They’d been on a ‘go slow’ for six weeks after demanding extra money for working on a coal face that was only 2 feet 8 inches in height. The average height of the coal faces in the St.Helens district was then between 3 feet and 4½ feet. The hewers were receiving 2s. 3d. per ton but said this had been for a yard seam and the seam they were now working on was much harder to work.

In 1953 a new locomotive shed was opened in the sidings at Lea Green, alongside the main railway line. This replaced the shed at Sutton Heath which had continued to be used, despite the closure in 1932 of Sutton Heath Colliery. This was because the brickworks at the rear of the colliery offices required a railway link, so the branch line to Sutton Heath was retained. On January 1st 1961 Lea Green became part of the NCB's West Lancashire Area, having previously been in the No. 3 (St Helens) Area of the North Western Division after nationalisation.

On June 6th 1962, The Times (of London) reported how police were searching for 'wreckers' who had released the brakes of two wagons loaded with coal as they were standing in Lea Green Colliery's sidings. The wagons rolled down an incline, smashed through a set of buffers and ended up straddled across the main line, just minutes before the Liverpool to Manchester express was due. The quick work of a signalman, who spotted the wagons and halted trains, averted a potential disaster and heavy duty cranes were brought in to clear the line. This kind of vandalism happened from time to time as youths looked for a cheap thrill, not realising the possible consequences of their actions.

In the early 1900s, the left hand line was identified as a 'mineral railway track', and part of its use was probably the connection through the colliery complex, up to and across Eltonhead Road, into the Sutton Heath Colliery complex opposite the Boars Head Hotel and then down to the clay pits of Sutton Heath Brickworks, situated behind Elephant Lane. The other two lines of the sidings in those busy years up to about 1950, would be used to marshal coal wagons from around the district - as well as general goods from factories in Rainhill, Whiston etc. - all with connecting lines. Such marshalling activities were carefully controlled by the signal boxes at Lea Green and Rainhill stations.

Steam locomotive 'Bellerophon' pictured at Lea Green Colliery during the 1960s<

Steam locomotive 'Bellerophon' at Lea Green Colliery during the 1960s

Bellerophon at Lea Green Colliery

In August 1962 it was reported that the Coal Board was proposing concentrating work on just one face at Lea Green. This would lead to 270 workers, who would no longer be required, being displaced to other collieries. Delegates at a Lancashire miners' union conference at Bolton on August 18th decided to oppose the move but it still went ahead. Before long the NCB decided to close the whole colliery with production ceasing in September 1964 (possibly August). During that year Lea Green produced 200,000 tons of coal and employed 600 men. The last remaining district on production at Lea Green was within Queen pit. Its under-manager Harry Foxley was reported to have said at the time of closure that the colliery still had a million tons of coal beneath it.

A small industrial estate occupied the site after the demolition of Lea Green Colliery and its sidings, although its locomotive shed and offices remained intact for many years. In 2005 outline planning permission was granted by St.Helens Council for a huge 'urban village development' on the site off Lowfield Lane. Based on an English garden theme, the Waterside Village development is set to feature large tree-lined boulevards, a village green and a series of natural water features.