An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 46 (of 95 parts) - Sutton at War Part 3 - Magnum Poison Gas Works

Part 4: What's Wrong With Sutton? | Part 5: War Diary of Lt. Harold Emblem

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me Research Sources

What's Wrong With Sutton? | Lt. Emblem War Diary

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Old Sutton in St Helens

Poison Gas Works

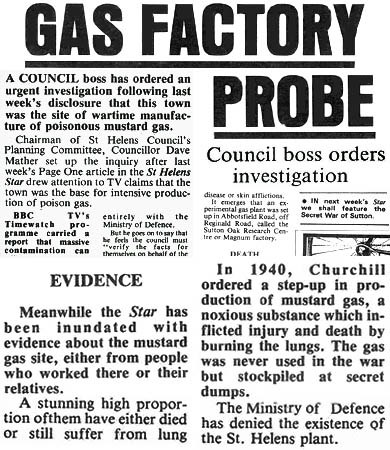

In a front page article in the St Helens Star of 18th April 1985, the newspaper revealed that they'd been 'inundated' with evidence about the works both from individuals who'd worked there and their relatives. 'A stunning high proportion', the paper commented 'have either died or still suffer from lung disease or skin afflictions'. This was in response to a BBC Timewatch programme broadcast on the 3rd of the month in which the Ministry of Defence had denied the existence of the Sutton Oak plant.

Industrial activity dated back to about 1880 when a manure works operated on the site. They were succeeded by James Robertson's Metal Works which occupied 15 acres plus 3½ acres of railway sidings. Robertson was a prolific Scottish inventor and engineer whose patents were employed locally at Sutton's Rolling Mill. In March 1896 the business became a limited company, known as the St.Helens Tube and Metal Co. Ltd. It was then described as 'tube manufacturers and merchants, millwrights, mechanical and manufacturing engineers, ironfounders, metal workers, merchants, &c.'.

In March 1897 Tubes Ltd. bought the company for £170,000. They made weldless tubes for water-tube boilers, which mainly had a marine use in powering ships. However the Birmingham firm closed their St.Helens plant in February 1899. Then from about 1905, Turner & Co. Glassworks were the occupiers, followed briefly by the Junction Glassworks. In 1909 the Magnum Steelworks took over the site and from February 1910 their foundry began making mild and manganese steel, castings and forgings. However they went into liquidation in July 1911, with the Magnum's plant and machinery sold at public auction on September 4th of that year. There does not appear to have been any further occupiers for almost four years.

Then in February 1915 the United Kingdom Chemical Products Company (UKCPC) bought the works on the site that then measured 16 acres. Its intention was to manufacture synthetic phenol and on April 1st 1915 a contract was signed with the Government. The latter undertook to pay the cost of installation of the required plant, pay the rent for the land and supply the raw materials at agreed prices. An additional contract was signed with the Government for benzol purification in July 1915.

There was much delay in the construction of the works, which eventually covered 82,811 sq. ft. In October 1915 a new agreement was signed that replaced the previous contracts. The factory was now controlled by the Government under its Explosives Supply Department. UKCPC began production in November 1915 and was required by the Government to produce three tons of phenol a day. However their output by the end of the month was at the rate of only one ton a day. It slowly increased and the Explosives Supply Department appointed a superintendent to improve matters.

However the Department remained unimpressed with the output of the UKCPC factory in St.Helens and in April 1916 terminated the contract. A month later the company was notified that the Government was taking possession of the works under the Defence of the Realm Act. The name was changed to H.M. Factory, Sutton Oak (although sometimes it was known as H.M. Explosives Factory) and by March 1917 the output of phenol had reached 4 tons a day. On March 29th 1917 a pay dispute between the Government and the National Union of General Workers (representing Sutton Oak staff) was settled by the arbitrator Harry Courthope-Munroe. It was mainly caused by the removal of overtime rates, which Courthope-Munroe partly restored.

The production of phenol at H.M. Factory, Sutton Oak ended in March 1918, through changes in the Government’s explosives programme. The factory was, however, adapted to produce arsenic compounds required for chemical warfare and production of diphenylchlorarsine began about November 1918. Records show that 260 people were employed at the plant in October 1918, of which 1 in 5 were women. Those who came into contact with the chemicals were given two weeks holiday after every six weeks work in order to clear the arsenic from their system. Special sick pay arrangements were also made.

Diphenylchlorarsine was first employed as a chemical weapon on the Western front during the trench battles of the Great War. However, by the time the Sutton Oak factory had begun production, the conflict was coming to an end and Sutton's stocks may not have been used. After the war the site closed for a period but exact dates are not yet known.

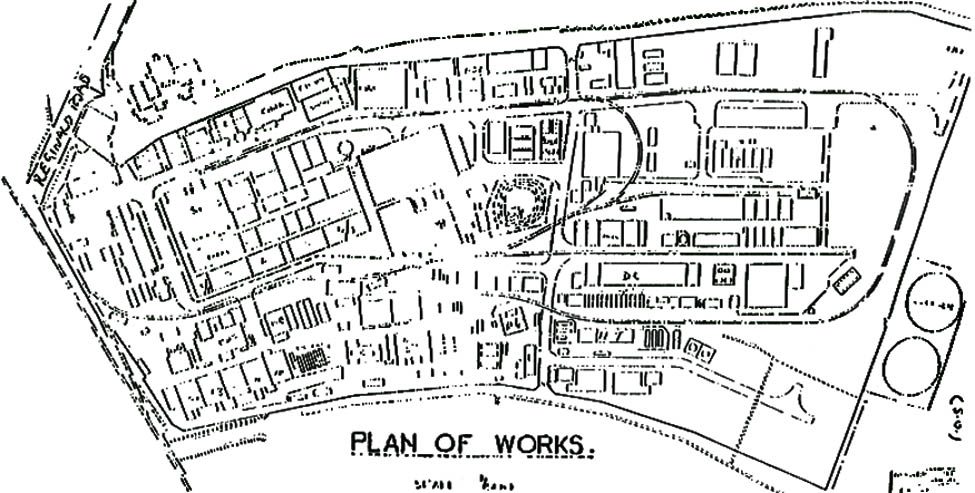

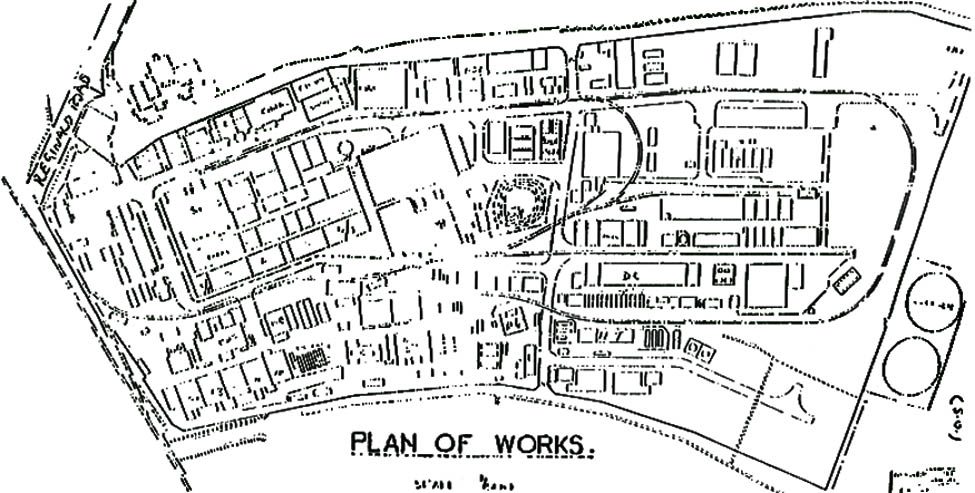

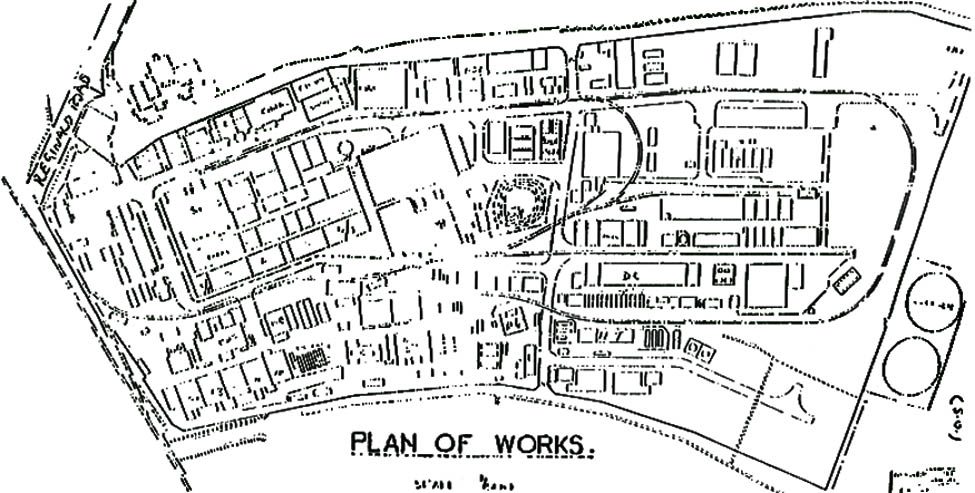

A plan of the Sutton Oak Chemical Defence Research Establishment works which was made in 1952

Plan of the Sutton Oak Chemical Defence Research Establishment works

A plan of the Sutton Oak CDRE

In 1925 many nations signed the Geneva Gas Protocol of the Third Geneva Convention as a result of public revulsion of the horrors of gas in WW1.The signatories agreed not to use 'asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases' in future, but didn't promise to stop researching and manufacturing them. Having been taken by surprise by Germany's employment of gas in the 'Great War', Britain wanted to ensure that it would be properly prepared if the need arose in future. It also reserved the right to use chemical warfare agents in retaliatory strikes.

More space was needed for the works, so the War Office issued compulsorily purchase orders on sixteen houses in Abbotsfield Road. This didn't go down well with the tenants, many of whom were mineworkers who were conveniently situated for the local collieries, especially Bold. However St.Helens Corporation agreed to build new houses for the families. An eviction was set for April 15th 1926, but the new houses hadn't been completed and at the last minute the Whitehall bureaucrats agreed to give the evictees more time to depart.

On February 16th 1927, The Times reported that the Secretary for War, Sir Laming Worthington-Evans, had assured Mr. J. Hudson, MP for Huddersfield, that no animal experiments had taken place at Sutton Oak. The Chemical Warfare Experimental Station at Porton in Wiltshire was known to test the efficacy of its poison gases on animals, which might have prompted the MP's question. This wasn't the only reference in The Times to Sutton Oak CDRE. Over the years, there were a number of job vacancies and other notices placed, making the Ministry of Defence's later denial of the plant's existence even more curious.

During 1927 and 1928 there was much correspondence between the Army Council of the War Office and the Treasury Secretary concerning the costs of hospital treatment for employees. The Council wanted free treatment for civilian staff at Sutton Oak and the Experimental Station at Porton who 'contract disabilities due to gas poisoning in the course of their employment' (letter from A. Widdows 13/6/1927). In the pre-NHS era, the cost of health care was an issue and if admitted to military hospitals, patients could be charged up to 12 shillings per day. Such hospitals were best placed to provide specialist care and it was felt important that doctors of the Royal Army Medical Corps should gain experience of such cases. Although the Council had the power to waive some charges in individual cases, it was felt that more patients would choose to be treated in military hospitals if they were certain it would be free. However with objections from the Air Ministry, the Treasury refused to agree to the Army Council's request.

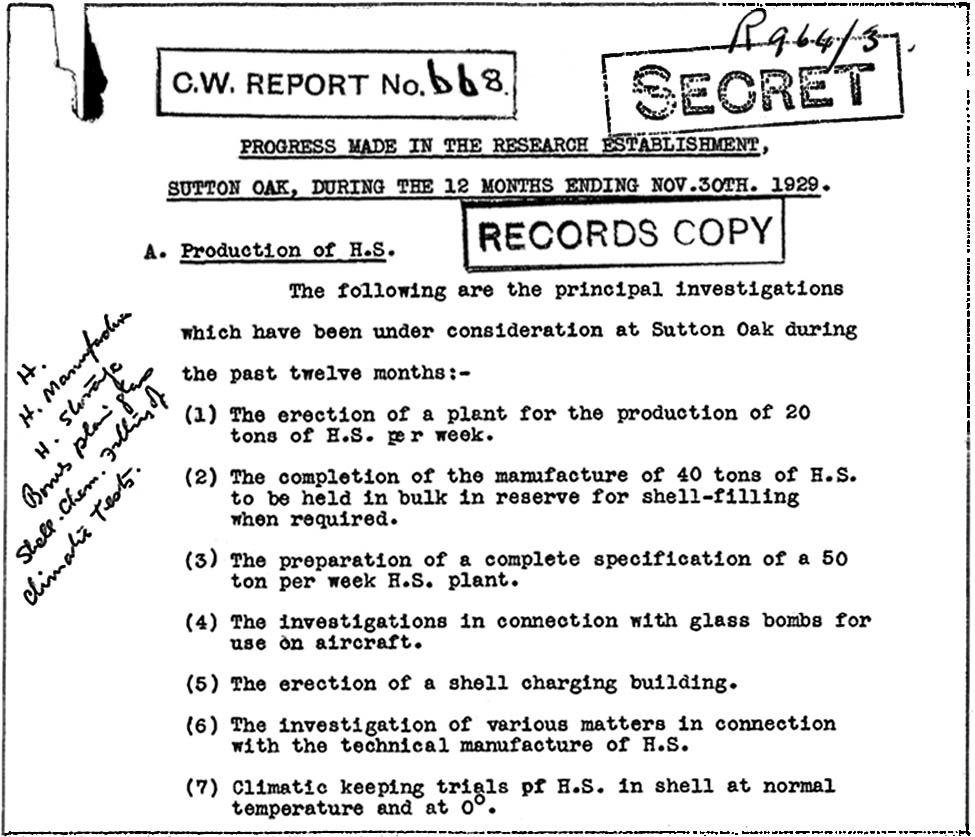

A Sutton Oak Chemical Defence Research Establishment progress report

Sutton Oak Chemical Defence Research Establishment progress report

Sutton Oak CDRE progress report

During WW1, gas had been deployed in three main ways: a) from inside cylinders that were carried by the wind; b) via artillery shells c) fired by the Livens projector. The latter was a large-bore mortar with 8-inch diameter tubes that propelled mustard gas cylinders over distances of up to 1700 yards. However, aircraft were increasingly being seen as the best means for deployment in any future conflict, although there were a number of difficulties to overcome. So Sutton Oak was busy researching the means of filling and charging shells for ground use, as well as developing 'baby' glass bombs for use in aircraft.

The documents describe the aviation work as being 'considerable', with many different types of bombs and packings experimented with. The latter was important as the Air Ministry had a rough usage test that had to be complied with. To pass the test, the small bombs had to survive a drop onto concrete from a height of six feet and so were encased within strong metal containers. The problem was that most bombs dropped from aircraft would fail to fracture unless they directly hit rock or stone pavements.

The Sutton Oak scientists were also experimenting with machinery that would automatically fill bombs with mustard gas chemicals. By 1929 they had developed a machine that would fill three per minute but knew that this was not fast enough. A progress report from April 1929 revealed that 40 tons of HS mustard gas had been manufactured during the past year and was in bulk storage 'ready for immediate use for shell filling etc'. Complete specifications had also been prepared for all materials and buildings required 'to enable any chemical manufacturer to erect a plant capable of producing 50 tons of H.S. per week.' The specification was complete with detailed drawings '…so that in the event of mobilisation it would be possible for several plants to be simultaneously erected in different parts of the country.'

From time to time some Sutton Oak staff had day trips away from the Abbotsfield Road site. For example in 1928 and 1929, reports document five trips made by the experts to the coast to inspect and make safe cylinders of chlorine or phosgene that had washed ashore. In September 1932 they went to Fleetwood to collect a mysterious cylinder that the tide had left on the town’s golf links. There had been considerable concern amongst the citizens of Fleetwood that the 14 cwt. container, which was almost 7 foot long, might contain poison gas and threaten the town.

However after carrying out tests back at Sutton Oak, the scientists were able to report that the object had been harmless. Later some personnel would, from time to time, travel across the country to dump waste products in the North Sea, accompanied by an armed guard. However it wasn’t until 1970 that the Ministry of Defence admitted that Britain had up until 1957, secretly dumped a total of 200,000 tons of dangerous chemicals onto the seabed. Another research establishment report of April 11th 1929 reveals how they supplied 'toxic materials' to the Crown Agents for the Colonies and to the Indian Army.

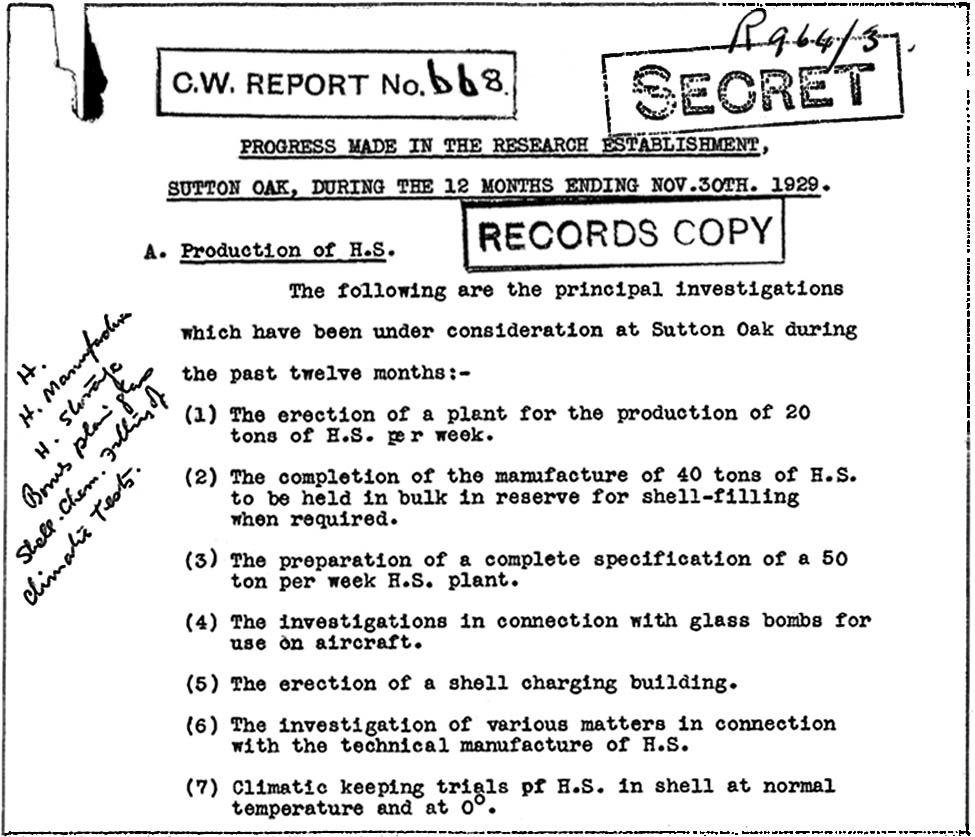

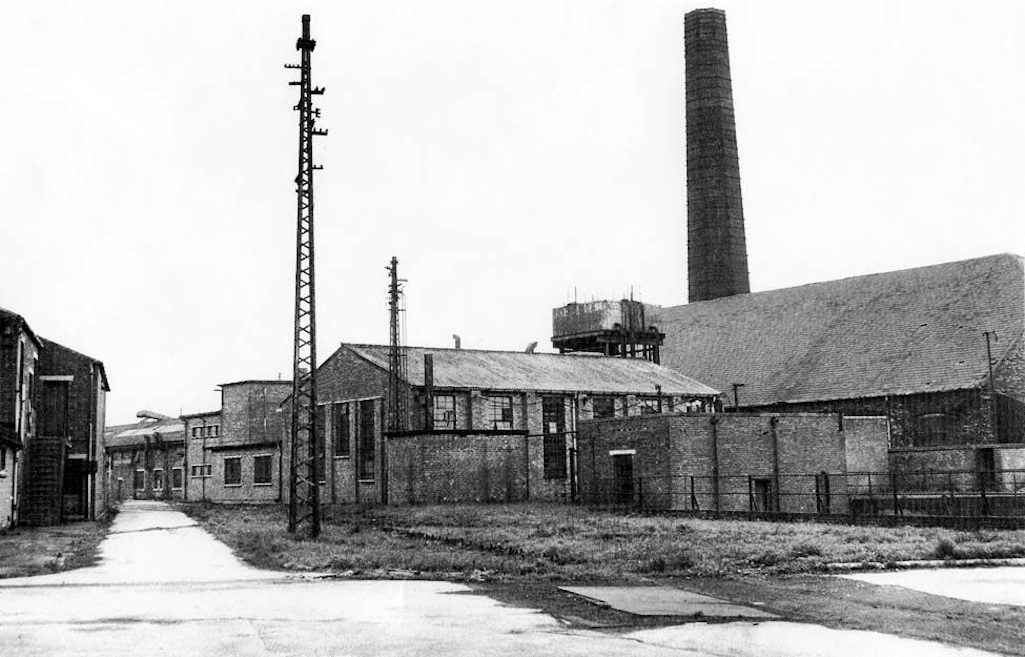

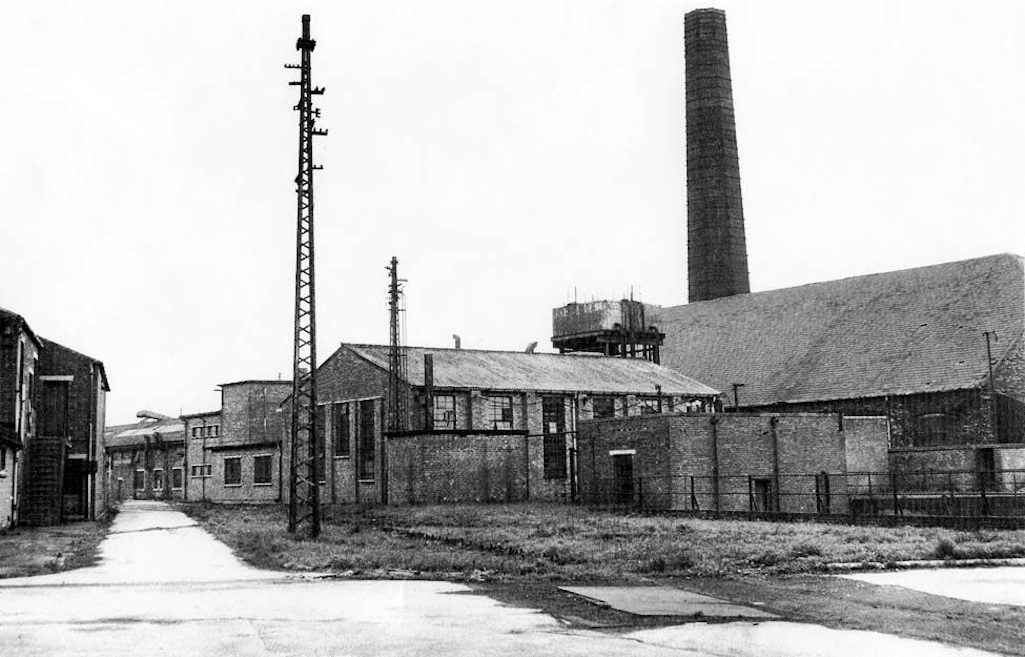

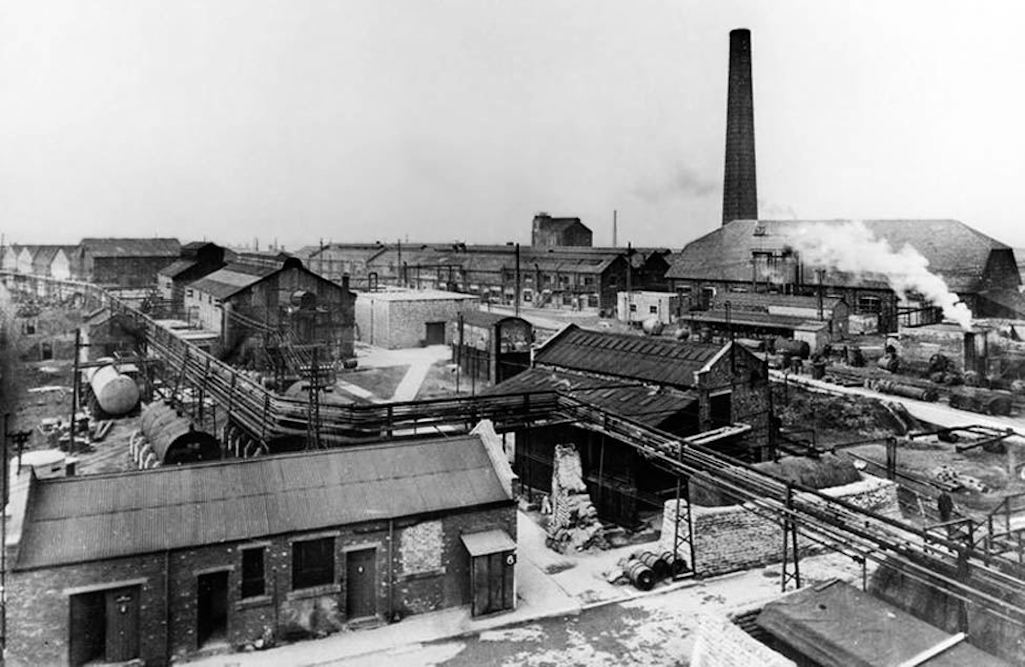

Some of the Sutton Oak CDRE workshops and the chimney which an American B-24 Liberator almost struck

Some of the Sutton Oak CDRE workshops and chimney

Workshops at the Sutton Oak CDRE

In early 1932, Woodward became the assistant to Professor Robinson, who had been granted a contract by the War Office to research chemical warfare problems. Neville Woodward felt that as a research station, Sutton Oak had been 'virtually moribund' for some twenty years. This is somewhat at odds with the documents described above, although he was probably referring to the facilities.

However, Woodward did feel that the conditions had greatly improved and were now almost ideal with a large, well-equipped laboratory. He was charged with identifying and developing a new variant of mustard gas that bore the codename 'HT' and was also known as 'Runcol'. The main chemical warfare agent used in WWI was called 'Pyro' or 'HS', as previously described. However it had a major disadvantage compared to Runcol. HS could not be used at altitude due to a high freezing temperature, so couldn't be employed in aerial gas spraying or in gas bombs. Having successfully completed his research into Runcol, Woodward left Sutton Oak later in 1932 after a 'stimulating' two years. He returned in 1937 for six more years, becoming head of the Research section.

Firemen attending to an incident or possibly on a training exercise at Sutton Oak CDRE (undated)

Firemen attending to an incident or possibly on a training exercise

Firemen at Sutton Oak CDRE

The investigation was conducted by Surgeon Commander C. E. Greeson who came to the conclusion that people who had previously suffered mustard gas burns had an increased sensitivity to skin applications of the compound. Perhaps a rather obvious conclusion, but the 7-page report of the experiment is of special interest to researchers as it details the participating individuals, their occupations and any history of burns.

The breadth of occupations is a reminder that the boffins were reliant upon a large number of support staff. Incidentally the chemists were involved in development work, while process workers were employed in actually making their creations or 'intermediate' substances. The table below features some of the details that were contained within the report. As well as burns and blisters, common medical complaints were erythema (skin reddening) and conjunctivitis. (Nb. 'H' refers to mustard gas).

| NAME | OCCUPATION | GAS BURNS | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|---|

| GREENOUGH W. | Labourer | No | Employed since 1923 as Fitter's Labr. Not on H.work, just working round place. This man & B. Rigby have worked together as fitter & mate for past 6 yrs. |

| TRIGG R. | Labourer | Yes | Employed since 1924. Labr. (previously process man). Came off process work 12.11.31, reason conjunctivitis, acute dermatitis thighs & scrotum. H. work off & on since 1924. No other history of burns. |

| TRIGG J.T. | Labourer | Yes | In works 9 yrs. For last 5 months employed as labr. Previously a process man. 15.9.24. Large burns both wrists (in hospital). |

| HARRINGTON F.G. | Blacksmith | No | N/A |

| ROBERTS J. | Labourer | Yes | 11.7.27. Labr. whilst clearing cess pit burnt. Inflammation eyes and scrotum. Small burn R.hand |

| WILLIAMS J. | Chemist | Yes | History of 12 years work with H. Still working. Burns in 1918 (blisters). Splash in eye (temporary blindness) 1918. Two small blisters in 1931. |

| ECCLESHALL W. | Chemist | Yes | History of several minor burns to extent of blistering over past 9 years. |

| FINN W. H. | Chemist | Yes | In 1921(?) burns R.arm & shoulder. Also history of several minor burns during past 9 years. |

| HUNTER J. | Lab. Asst. | Yes | Lab.Asst. since 1922. 26-3-31 History of erythema of body & conjunctivitis. 19-2-30. Burn of R. wrist. |

The document does not state a sampling methodology but it seems reasonable to assume that the 56 staff members were representative of the workforce. They comprised 18 labourers, 7 chemists, 6 lab assistants, 6 fitters, 5 process men, 2 clerks, 2 draughtsman, 1 store keeper, 1 medical attendant, 1 foreman, 1 painter, 1 electrician, 1 erector, 1 engineer, 1 joiner, 1 bricklayer and 1 blacksmith. The breadth of occupations is a reminder that the boffins were reliant upon a large number of support staff. Incidentally the chemists were involved in development work, while process workers were employed in actually making their creations or 'intermediate' substances. As well as burns and blisters, common medical complaints were erythema (skin reddening) and conjunctivitis.

Sutton Oak C.D.R.E. had been researching and making toxic smoke known as D.M. since 1922, although actual production ended during the following year. Stocks were used until 1937 when testing ejection containers that were needed to launch it against an enemy. However the 1920s D.M. was considered low quality and so the Sutton Oak chemists developed an improved process that produced a much better purity and yield.

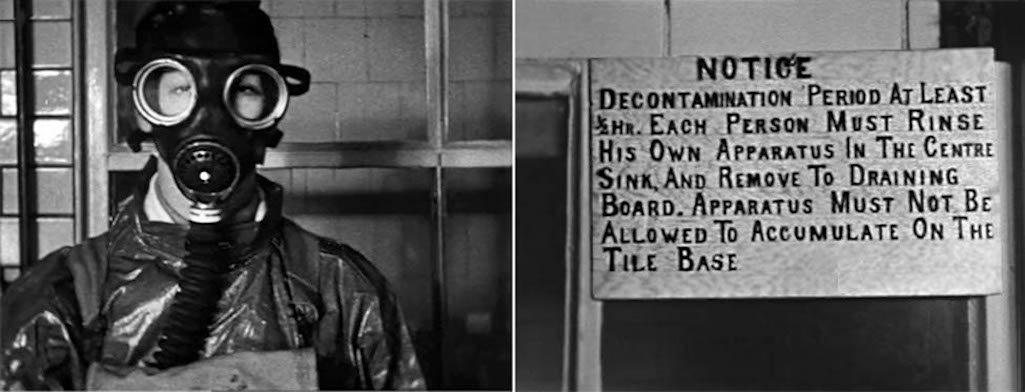

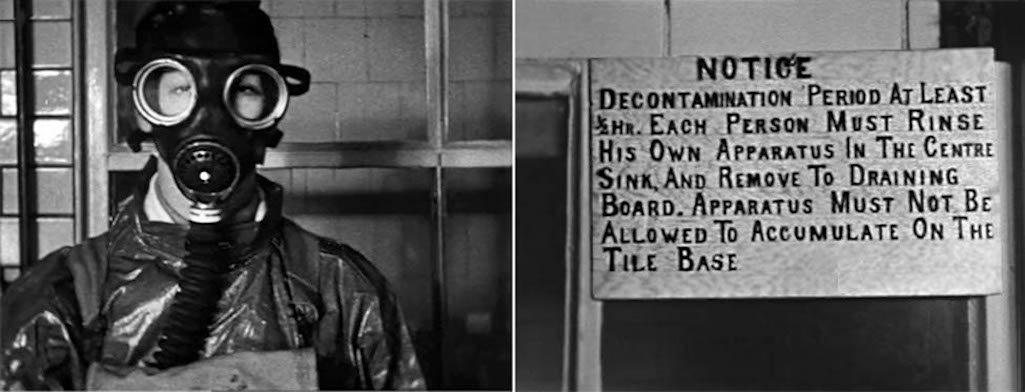

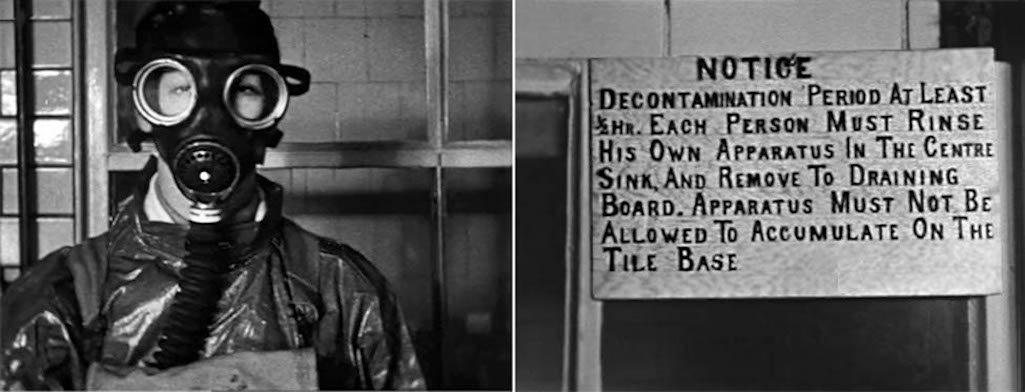

Inside the plant c. 1941 with a worker wearing a ventilator and a notice regarding decontamination of equipment

Inside Sutton Oak Chemical Defence Research Establishment c.1941 with a worker wearing a ventilator and a decontamination notice

Inside the Sutton Oak plant c.1941

Also that year, on May 24th 1937, a research document entitled ‘Report on the Boiling of Civilian Clothing Including the Decontamination Thereof at Sutton Oak’ was issued. They came to the conclusion that they should in future 'segregate garments of light shades from those of dark shades' to prevent 'running of dyes'. Perhaps the men conducting the experiments in their laundry should have just asked their wives and saved some time! They also decided that the optimum time for decontaminating undergarments by boiling was 30 minutes for HS and 60 minutes for HT.

The Sutton Oak Research Establishment's pilot production plant was also a de facto factory. In 1939 a Ministry of Supply memorandum marked 'Secret' stated that Sutton Oak had the capacity to produce 50 tons per week of 'spray' mustard gas. The total UK stockpile when war broke out was only 10 tons and there was no Runcol production at Agency factories until March 1940. So for a period of six months from September 1939, the whole of the country's supply (1100 tons) came from Sutton Oak. This is revealed in a 1945 memorandum which also stated that:

These chemical warfare agents had all been manufactured at Sutton Oak and stocks were also used to protect British beaches from a German invasion. It's also worth mentioning that through the development work at Sutton Oak and Porton between the wars, mustard gas was now four times more effective than in 1918.

The chemical defence research establishment during WW2, taken by Graydon Carter © IWM (HU 102403)

The chemical defence research establishment during WW2 (by Graydon Carter)

The research establishment during WW2

Their remit was to 'devise processes for the ultimate production of chemical warfare agents required by the services; to prepare batches of such agents required for field trials, supply analytical services and carry out background research.' There was also an Engineering Group and Plant Development Section. A small photographic section provided photography services and also made safety films. In Memories of Sutton 1, David Normington Gerrard describes how his photographer father Arthur Normington received a bad mustard gas burn at the plant during the war, which forced him to give up his work there.

Soon after the Americans entered the war in December 1941, a top level three-man mission visited Sutton Oak to ascertain how the US Office for Scientific Research and Development could assist the chemists' work. This was led by scientist and educator Professor James Bryant Conant, who later became the US Ambassador to Germany.

The Sutton Oak facility had ceased manufacturing mustard gas by mid-1940 and had returned to being solely a research unit. During the rest of the war, production using the Sutton Oak template took place mainly at Randle with support from Valley Works (Rhydymwyn) and at Springfields. They made a mix of chemical warfare products for potential employment by the RAF and the army. These were mainly mustard gas bombs (HM) and spray gas (HT) for the former and mustard gas-filled shells (HM) for the latter. Phosgene, tear gas and toxic smoke stocks were also made but in lesser quantities. The emphasis at all times was on a defensive, retaliatory use. It would take a German gas attack on Allied soldiers to initiate a British use of chemical weapons.

In 1943 a full-scale operational plant was constructed at Sutton Oak for test and experimental purposes manufacturing a warfare agent codenamed 'S'. By the following year the research establishment was producing up to fifty tons a week of 'S' for experimental purposes. As well as mustard products, the boffins were also researching T.773, arsenicals and di-iso-propyl fluorophosphate.

During the half-year ending December 31st 1943, a total of 88 staff had a total of 1183 days medical leave that was recorded as 'recuperative'. The facility published a monthly 'Toxic Accident Report' which for May 1944 revealed eight injuries that required a total of 77 days medical treatment. One poor soul had to have 11 days treatment on his genitalia and another worker spent 14 days at a convalescent home after chlorine exposure. Many injuries were blamed on staff not following the safety practices.

To treat injured personnel from such accidents, a new medical station was opened at the research establishment during 1943. It had a full complement of nursing staff and at least one doctor, who were able to quickly deal with both emergencies and minor accidents. During this period, the Medical Officer was A. McLaren Ferrie working under Sutton Oak's Superintendent J. W. C. Phillips. Staff were often treated at the Royal Southern Hospital in Liverpool where the research establishment's own dermatologist Dr. Stopford Taylor and eye specialist T. J. Phillips were based.

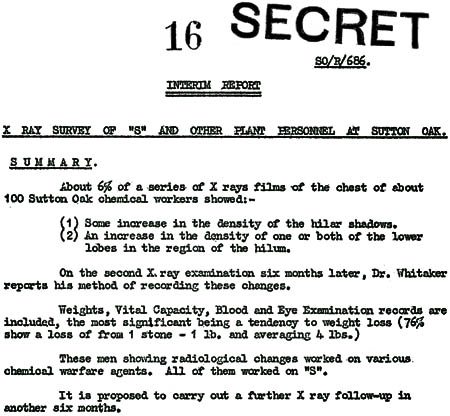

In November 1943, the interim results of a health study at Sutton Oak were revealed. It was motivated by concern that many workers employed at similar research plants had developed a 'constant chronic cough'. So Liverpool radiologist Dr. P. H. Whittaker studied 105 workers, primarily to evaluate any changes in the men's lungs after working with chemicals. When given chest X-rays for the first time, 17 of the men displayed radiological problems with their lungs.

Six months later the men were X-rayed again and 6% had developed changes in their lungs which were considered to have 'pathological importance'. However, Dr. Whittaker was unable to ascertain the effects of long-term exposure to chemicals, which might only be displayed in later life. His report also stated that 76% of the workers had lost weight over the six months of his study.

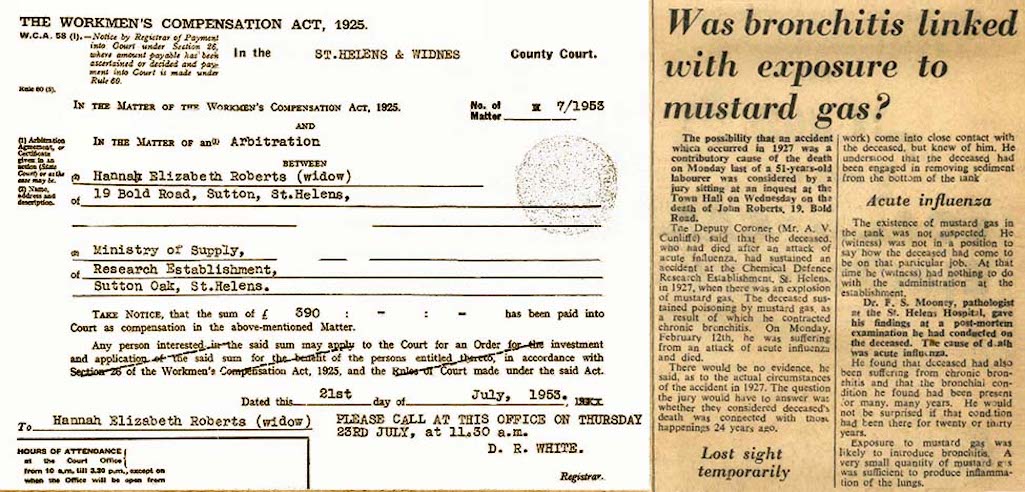

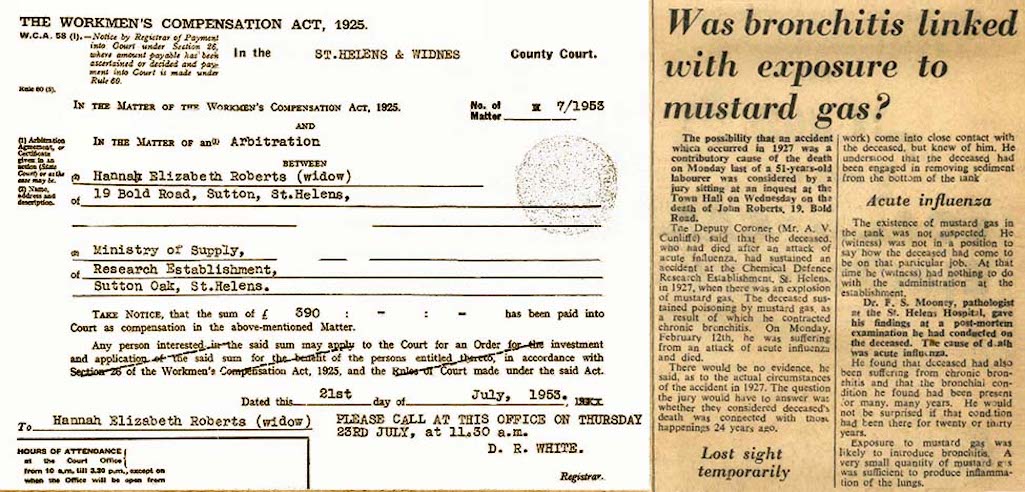

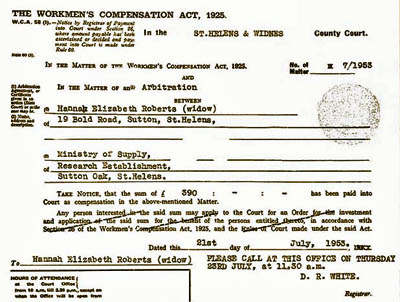

Obtaining compensation for lung problems after exposure to gas wasn’t easy, even after death. In 1927 John Roberts was asked to remove some sediment from a tank at the research establishment, which led to some serious mustard gas exposure. As a result the 27-year-old labourer spent three weeks in hospital and for a while lost the use of his eyes. Roberts returned to work but the accident left him with a cough and in February 1951 he died from acute influenza linked to chronic bronchitis.

This was the conclusion of Dr. F. S. Mooney, a pathologist at St Helens Hospital, after conducting a postmortem examination on Roberts’ body. He believed that the bronchitis was of a longstanding nature and was a direct result of the accident some 24 years earlier. However at Roberts’ inquest, the research establishment’s own medical officer, Dr. G. N. Humphreys, denied a connection between the accident and the bronchitis. The coroner’s jury disagreed and brought in a verdict of death by misadventure, adding that the bronchitis was an effect of the 1927 accident.

Left: Hannah Roberts' compensation award; Right: St Helens Newspaper February 16th 1951 - Contributed by Graham Hill

Hannah Roberts' compensation award and St Helens Newspaper 16/2/1951

Hannah Roberts' compensation award

Harry Hickson was born in Sutton Leach in 1937 and remembers well the Magnum, as locals called it:

Sutton Oak CDRE fire brigade - contributed by Stan Bate whose father James is back row 5th from left

Sutton Oak CDRE fire brigade - James Bate is on the back row 5th from left

Sutton Oak CDRE fire brigade

Many of their research staff had gone to the disaster scene leaving their work in limbo and the bosses were concerned that they might soon have an emergency of their own. The research unit's Tower is believed to have had a large water tank, which provided additional pressure for the fire crew along with their booster pumps. The top of the Tower had an observation deck built in, which, as Harry mentioned above, was especially useful during WWII.

Towards the end of the war, a secret memo called for a merger between Sutton Oak and the Valley Works factory at Rhydymwyn near Mold. The report from May 1945 and obtained by the Rhydymwyn Valley History Society, drew attention to problems with the Lancashire plant's location. The memo said it was on a 'bad site' in 'grim' industrial surroundings adding that the:

The CDRE fire brigade c.1945 contributed by Stan Bate whose father James is back row third from left

The CDRE fire brigade c.1945 - James Bate is on the back row 3rd from left

The CDRE fire brigade c.1945

However in April 1945 the Allied troops began capturing German chemical dumps and the 'secret' was certainly out. Samples were flown to Sutton Oak and in 1946 a nerve gas project was established on the site to develop improved versions of the German agents. A document dated January 15th 1948 and marked 'Secret', details the primary aims of the Project at Sutton Oak as: (a) the production of one ton of a nerve gas (probably G.B.) for essential experimental purposes. (b) the design and operation of a one ton/week unit for the production of G.E.

'GB' is the designated code for the deadly sarin, which is 500 times more toxic than cyanide. 'GE' refers to the lesser-known and less potent ethyl sarin, but which still causes death in less than 15 minutes. The letter 'G' incidentally stands for 'Germany'. The two substances were so dangerous to make that a doctor had to be present in case of accidents, so rapid treatment could be given. The report detailed the progress of the Project so far at Sutton Oak.

These nerve agents require the production of intermediate substances, which in GB's case is MePOC12. The document stated that a large quantity of MePOC12 had been made over the previous 12 months and was ready to be converted into GB (sarin). The engineering arrangements had been put in place to create sarin at the rate of 1 1b. per hour, once a full-time doctor was available.

The key intermediate for GE is EtPOC12 and a large amount of laboratory work had been undertaken on various methods of preparation. The favoured means of making EtPOC12 was using lead tetraethyl, however it was described as 'exceedingly toxic', with workers required to have a 'thorough medical examination at frequent intervals'. The Sutton Oak Superintendent also wrote that: 'The previous medical background of the Establishment causes some misgivings as to the fitness of a significant percentage of those likely to be engaged on the type of work visualised'.

Engineering arrangements had been made to create around 1 cwt. per week of EtPOC12, although the Superintendent would not authorise its start until a doctor was available. Like many workplaces at the time, Sutton Oak CDRE was experiencing a post-war labour shortage and this included medics and chemists.

A further secret document dated October 5th 1948 reveals that 31 staff were engaged at Sutton Oak on what they referred to as their 'G programme'. Some were allocated research briefs while others were involved with development of the nerve agents. The workforce comprised scientific officers, experimental officers and scientific assistants but the total number of staff excluded safety officers, engineers and ancillary staff. The report stated that involvement in G work caused workers a 'considerable nervous strain' that might lead to a 'frequent lay off period for recuperation purposes'.

Staff members wearing protective oilskins in the 1940s - the left hand photo is outside the toxic sample stores

Staff members wearing protective oilskins in the 1940s - the left hand photo was taken outside the research establishment’s toxic sample stores

Wearing protective oilskins in the 1940s

After considering fourteen potential sites, Nancekuke near Redruth in Cornwall was chosen as the new location for developing nerve agents. It had served during the war as an airfield for RAF Portreath and was taken over by the Ministry of Supply on July 28th 1949. However it took several years to convert and so work continued at Sutton Oak. Research and manufacture of sarin had ended in 1947 after around 18 months work, with approximately 1 tonne of the agent produced. The focus was now on ethyl sarin (GE) and a total of about 330kg was produced between 1946 and 1953.

This was relatively small with full scale production only taking place when Nancekuke was operational. Over the seven year period, Sutton Oak concentrated its research and manufacture on the precursor agents required to make ethyl sarin and sarin. Some of these intermediate agents were stored at the St.Helens plant and then shipped to Cornwall. The Sutton Oak staff also designed the large-scale, one ton a week sarin production plant that was built at Nancekuke.

On April 14th 1950 the Daily Express reported that American G-Men and MI5 spooks were making intensive enquiries at Sutton Oak and Porton. This was in the light of the Klaus Fuchs scandal. He was the physicist and atomic spy who six weeks earlier had been convicted of supplying Manhattan Project secrets to the Soviet Union. The US detectives had been despatched across the Atlantic to investigate Britain’s security arrangements.

Chapman Pincher, who would later publish the controversial book 'Their Trade is Treachery', wrote the Express article. Although Government officials discounted a suggestion that leaks of secrets were being tracked, Pincher argued that their inquiry seemed to be far more thorough than the routine checks made in other defence establishments. The article stated that the Americans were especially sensitive to information relating to poison gas research, as they rated the nerve gases second only to atomic weapons as deterrents to an attack.

The new Chemical Defence Establishment Nancekuke was opened in 1953 and Dr. J. W. C. Phillips, the Superintendent from Sutton Oak CDRE, was transferred along with forty staff members. Some laboratory equipment dating from the 1930s was also taken but never used and was eventually broken up and buried in mine shafts. Some plant is also believed to have been transferred to the Randle Works. It took time to wind down the Sutton Oak site and it wasn't until 1954 that it completely closed. The facility's laboratories were dismantled and the site was thoroughly decontaminated.

However many of the site's original buildings remained until the 1970s and some was used by civil defence and auxiliary fire service staff for training purposes. Eventually the Abbotsfield Park Industrial Estate was created, which is home to a variety of businesses. CDE Nancekuke in Cornwall closed in 1980 and is once again RAF Portreath. In 2006 a chemical weapons scare was sparked when a digger driver accidentally unearthed some Sutton Oak equipment. Specialists from the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory were called in to test for chemicals, although none were found.

Although most of the wartime chemists, scientists and technicians at Sutton Oak had been recruited in London, many Suttoners undertook jobs as their assistants and also provided ancillary services. Secrecy meant that all work had to performed in-house, whenever possible, so blacksmiths, electricians, welders, painters, glaziers, joiners and fitters were employed with their own workshops. Highly skilled workers created a range of light engineering equipment and they constructed labs of complicated design, so the boffins could research the warfare agents and pilot manufacturing methods.

After the closure of the plant and with all staff having signed the Official Secrets Act, Sutton Oak CDRE was largely forgotten. Various companies - such as Barton's Engineering, Rutland House Veterinary Hospital and Matthews Office Furniture - established themselves on the site and it wasn't until 1985 that memories were revived with the BBC Timewatch broadcast. The subject of the documentary was the manufacture of mustard gas during 1939-45 and it was the Ministry of Defence's supposed denial of Sutton Oak CDRE which so enraged many people in St Helens.

The broadcast claimed that massive contamination can exist for forty years after chemical warfare plants have stopped production. So Dave Mather, Chairman of St Helens Council's Planning Committee, set up an inquiry, although investigations revealed no ground contamination at the Sutton Oak site. The St Helens newspapers received numerous letters as a result of the controversy and the Reporter on May 13th 1988, published a letter from an individual who used the initials L.0.S. The writer stated that their father and two uncles had worked at Sutton Oak during its early years:

Included in the production is the: 'Arrival of new employee: medical exam: issue of overalls, protective clothing, respirator: training school for general instruction and identification of war gases. Demonstration of correct method of wearing protective clothing for various processes. First aid treatment after mustard contamination: decontamination of skin: instruction in handling toxic materials.' The film also shows examples of accidents and demonstrates emergency procedures.

Frank Grayson reveals in his research that sufficient interest was shown by the Russians in inspecting the site of the former mustard gas works that in July 1996 a senior RAF liaison officer turned up to survey the area. Although in the end the Russians failed to make a request, it is believed that official visits have taken place from other nations (including possibly China) to the Abbotsfield Road Industrial Estate. Any foreign powers making inspections in the future, might like to view the remarkable tenant T. M. Utley, who when based in Liverpool in 1912, made the bells and 900 portholes for the Titanic.

So what was the point of Sutton Oak Chemical Defence Research Establishment if the only people who were ever affected by its chemical agents were its own staff, and perhaps, local residents? Rather like nuclear weapons in the post-war world, the mustard gas stocks that were built up during WWII from Sutton Oak's designs, processes and at least six months of production, were used as a deterrent against use by the Germans.

A hard lesson had been learnt from the horrors of mustard gas in the first world conflict and the British did not want it repeated. However, the Italian Fascists had used chemical warfare in their Ethiopian campaign of 1935-6 and the Nazis had been building up their mustard gas stocks during the 1930s. They had an unpredictable leader and Hitler would probably not have thought twice of ordering chemical warfare against the Allied forces and British citizens. However, he knew that retaliation would immediately take place and the War Office had even created plans to attack German cities with mustard gas if the Germans struck first. So arguably Sutton Oak played a pivotal role in saving many lives and it's a chapter in Sutton's history that we should, perhaps, be proud of and certainly not ashamed.

The site of the gas works is now the Abbotsfield Park Industrial Estate