An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 94 (of 95 parts) - History of Sherdley Colliery (1870s - 1944)

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me

Bold Colliery Pt. 1 | Sutton Manor Colliery Pt .1

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Their colliery company – founded in 1824 by brothers John, James & Peter Bourne along with Robert Robinson – mined extensively in St Helens during the 19th century. Their mining lease from the Hughes family commenced in 1826 with the operations of Sutton Colliery, situated off Peasley Cross Lane. This continued until 1856 when Robert Robinson left the partnership, and the Bourne's renamed the venture Peasley House Colliery.

Further positive coal seam exploration resulted in 1872/3 in the renaming of Peasley House Colliery to Peasley Cross Colliery, as well as the establishment of Sherdley Colliery. Between 1876 and 1883 five members of the Bourne family died and this prompted their heirs to sell the coal operations, with the Whitecross Co. Ltd. of Warrington (formerly known as the Whitecross Wire & Iron Co.) purchasing both collieries on February 1st 1887.

Joint management of both collieries continued for a number of years, but the Peasley Cross operation slowly wound down, resulting in the Whitecross Company selling these coal activities, with the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Colliery Co. becoming the owners in 1903.

Sherdley Colliery dates back to at least 1873 when it was first mentioned in the Mines List, which referred to two shafts being worked. This website has identified 46 deaths at Sherdley, although there were probably many more. The first recorded fatality occurred on January 9th 1874, when 37-year-old collier John Glynn was crushed by a stone. Then on December 18th 1878, 35-year-old Michael Boyle died from a fall of roof after ignoring a warning from a fireman. Robert Davies (or Davis) died through rupture of the bladder, as a result of an accident that took place on January 4th 1879. The 32-year-old collier was crushed between the tub of coal that he was pushing and a runaway tub that had broken loose.

Two miners - 52-year-old Philip Carter and Thomas Price aged 25 - were killed as a result of an accident on February 26th 1879. They had disturbed some of the supporting timber when repairing an underground road, causing a roof to fall. The colliery was then managed by William Lee, who also managed the nearby Peasley Cross Colliery, with Robert N. Turner (b. Durham c.1837) listed as manager of both collieries in 1882.

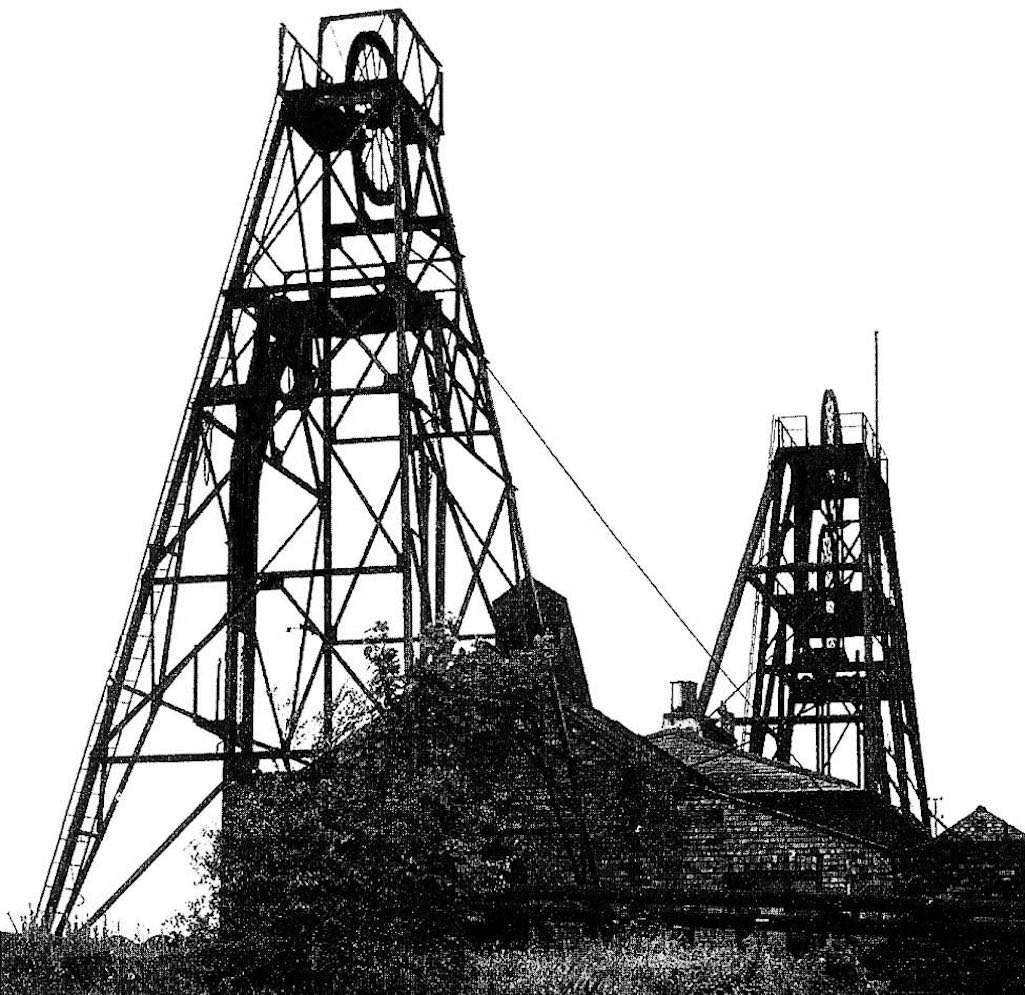

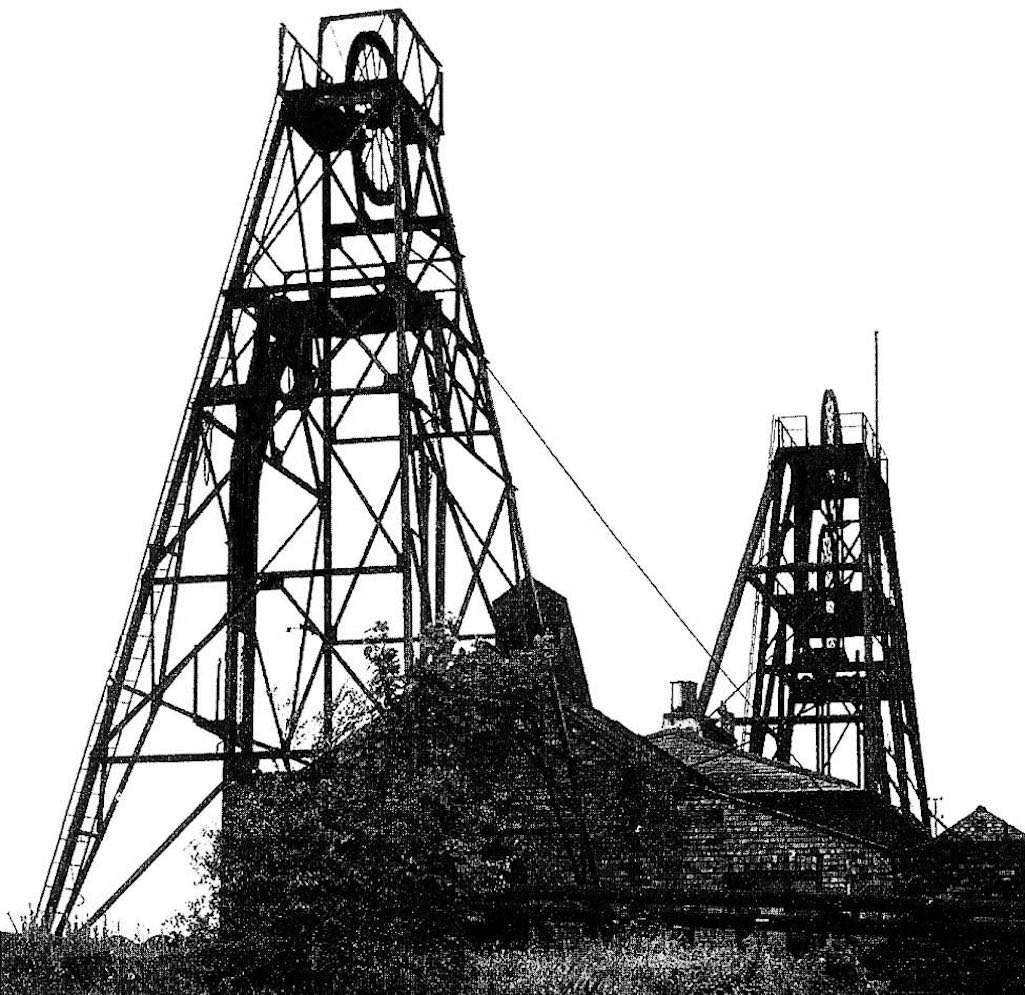

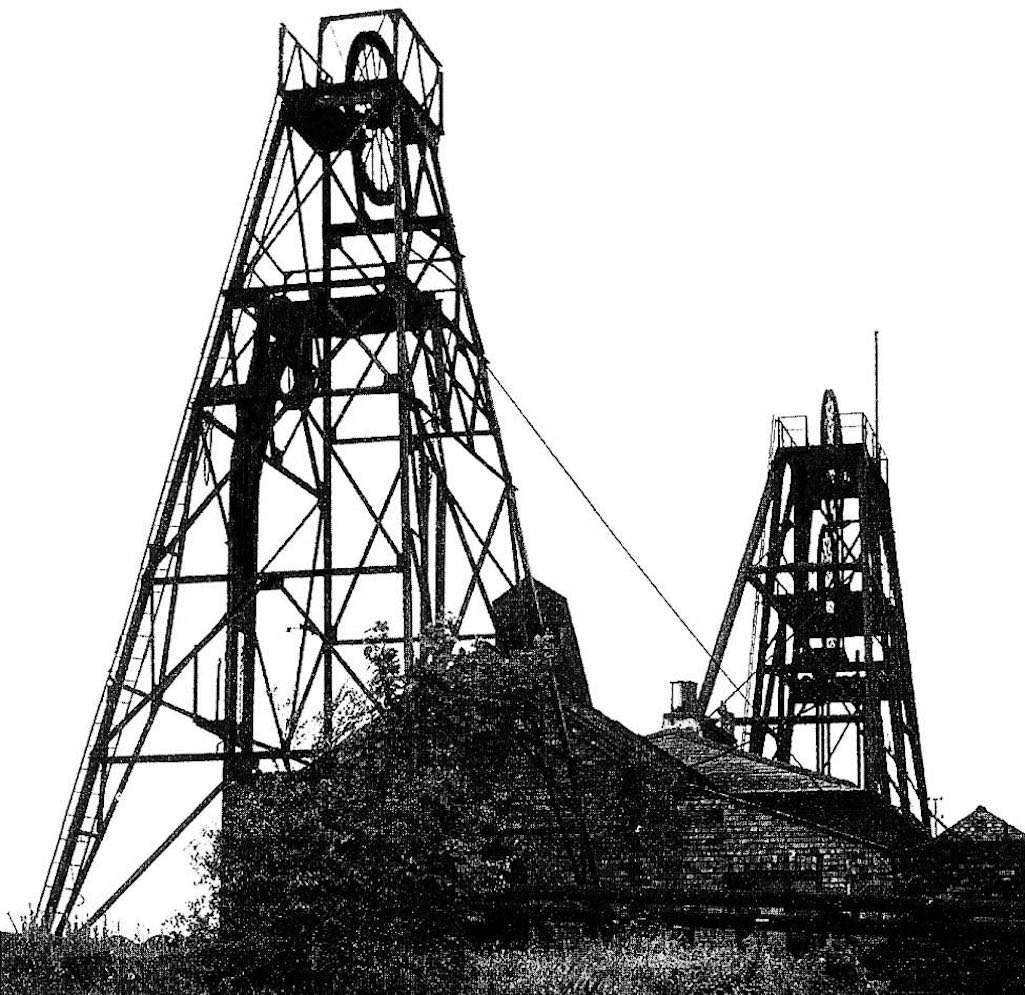

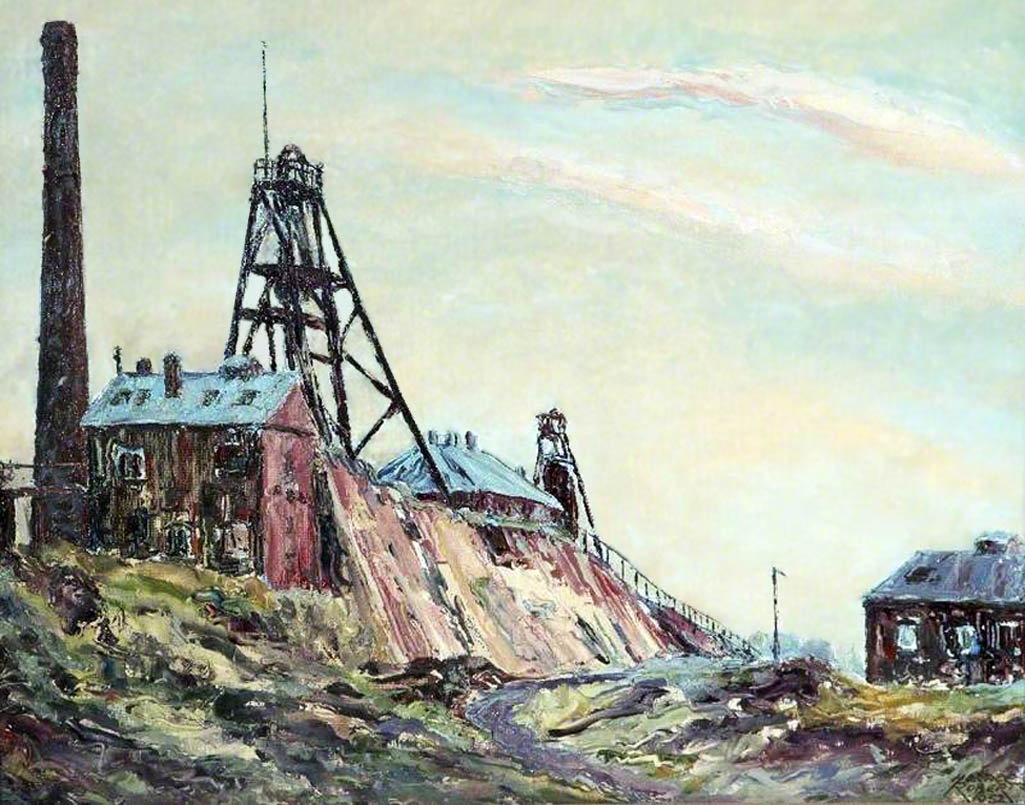

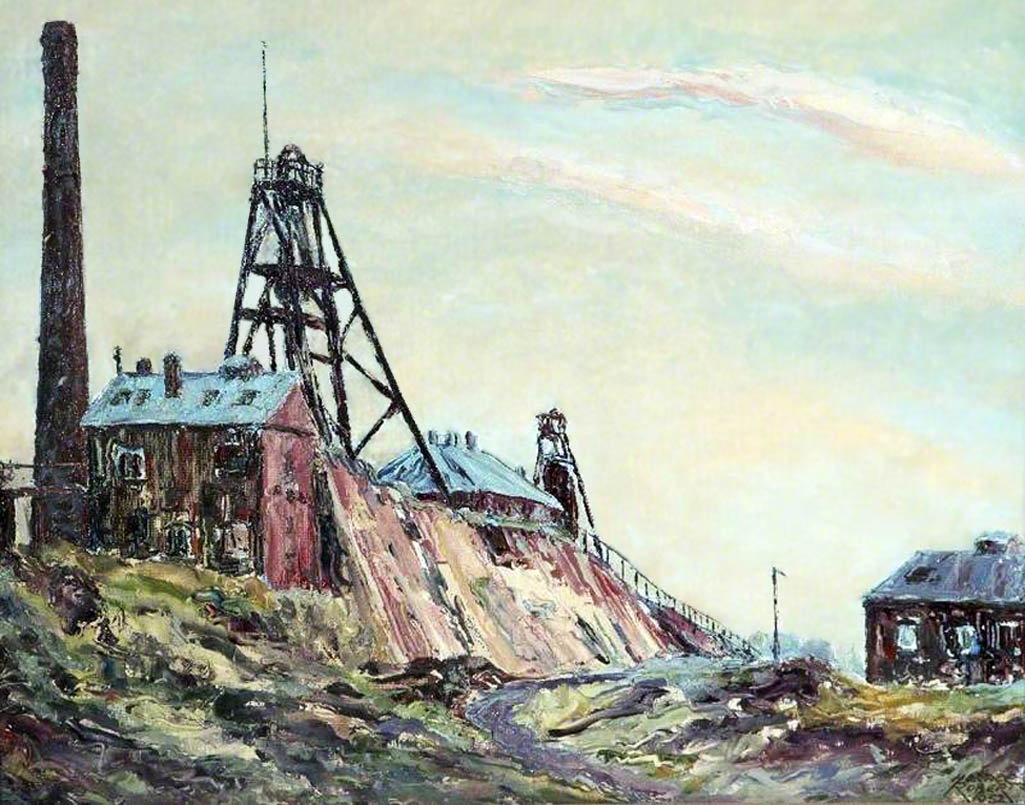

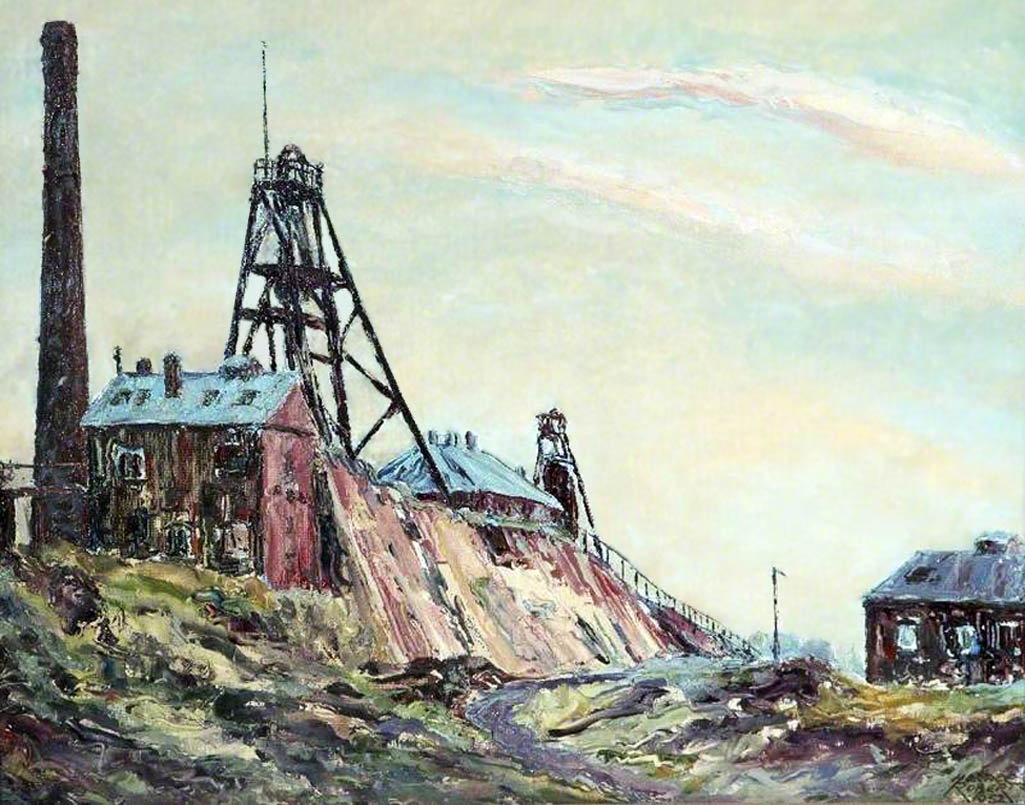

Sherdley Colliery’s headgears which dominated the skyline for many years after its closure in 1944

Sherdley’s headgears dominated the skyline for years after it closed in 1944

The headgears of Sherdley Colliery

Insufficient timbering that caused roof collapses was a recurring aspect of many deaths down Sherdley Colliery. However James Bridge lost his life on March 13th 1883 through a pit cage accident. He attempted to get into the cage after it had been signalled away and after he had been warned not to enter. The cage was lowered just as he was getting in and the 65-year-old engineman was crushed.

On March 21st (or 22nd) 1883, 18-year-old Lambert Anders was killed almost instantaneously at Sherdley after being caught between two ‘jigger boxes’, which were in motion. Thomas Thompson, aged 37, died on September 27th 1883 while clearing part of a roof fall in order to set a prop, when a piece of stone suddenly fell on top of him.

Fireman John Davis, aged 33, died on April 2nd 1887 also died as a result of a heavy stone falling. During this time workers were only paid for the work that they did, which was often on piece-rate, and it was anathema to employers to suggest that they should give their staff paid holidays. However the better bosses provided morale-boosting annual day trips and in June 1887 Sherdley Colliery staff were treated to an excursion to Southport, with 800 employees reported as visiting Blackpool in July 1889.

By now the authorities were paying more attention to the regulation and inspection of collieries and on November 9th 1888 the Whitecross Colliery Company and their manager Robert Turner found themselves in St.Helens Police Court. They were charged with permitting the firing of shots (detonation of explosives) down Sherdley Colliery, where explosive gas existed. The bench fined the manager just 20 shillings and dismissed the summons against the owners.

A curious court case took place six weeks later when Christopher Dingsdale of Marshalls Cross Road was summoned by his manager, Mr. Turner, for opening a safety lamp down the mine. He’d been drinking in a local pub (probably the Bull & Dog) and was heard boasting that while working down Sherdley he had unlocked his lamp with a pick point and then used the flame to fire a shot. This was a dangerous practice but eavesdropping inside the inn was Richard Marsh, who was the manager of Phoenix Colliery at Ravenhead. He got in touch with his opposite number at Sherdley, who initiated the prosecution against Dingsdale, and the magistrates fined him 20 shillings, plus costs.

Underlooker John Leigh, aged 38, was killed on October 29th 1890 while underground at Sherdley. He was walking along a road with the pit’s manager and surveyor, when a stone caught him after suddenly falling from a pothole. Very dense stones dropping from the pit roof without warning was a danger that all miners were wary of. They were essentially comprised of ironstone material of a cannonball size and would weigh up to 15 to 20 cwts, having been formed in sedentary rock deposits millions of years ago. A layer of coal about half an inch thick surrounded them, which is why they easily 'popped out' with only the slightest roof movement. Whilst some mines had more large stones than others, they were very difficult to see. If they were, for example, located in a main tunnel, with appreciable height and not covered by timber, their density / weight falling only a few feet onto a miner’s head would cause serious injury if not death.

Another Sherdley miner prepared to risk his own and his workmates safety was John Boardman. On the morning of May 13th 1891, a fireman named Owen caught the collier from Oldfield Street puffing away on his pipe underground. There was an unlocked safety lamp by his side, suggesting that he had deliberately unlocked it to light his pipe. An 1872 Act of Parliament had made it a legal requirement for lamps to have a lock mechanism to prevent miners from opening them. But like Christopher Dingsdale, Boardman had found a way to unlock his lamp and he was prosecuted for the offence and fined ten shillings.

On October 2nd 1891 John Connolly and Ralph Talbot had narrow escapes from death when large quantities of stones and dirt fell on the pair while they were timbering the roof of a roadway underground. It was two hours before their groans were heard and a further 1 – 2 hours before they could be extricated, after enduring what the Manchester Courier described as “terrible suffering”. The colliery’s own horse-driven ambulance removed them to the Cottage Hospital nearby. Amazingly no bones were broken but both men were badly crushed. A rumour spread that they had both been killed and this was even printed in a St.Helens newspaper. This led to one of Talbot’s sons visiting the hospital in tears asking to see his father’s body and he was amazed to find his father conscious in a hospital bed.

Like all businesses, collieries required office staff in order to function. For some years Enoch Grime served as cashier at Sherdley Colliery and he was also chairman of Sutton Conservative Club. For a couple of days in March 1892 Enoch had a slight cold but attended to his duties as normal. However he rapidly deteriorated and within twenty-four hours he was dead. His son Edward Grime, incidentally, was a well-known professional singer. On November 23rd 1892, William Brown, aged 40, died after being crushed by a fall, after cutting coal from a high level without setting props to protect himself.

An unusual accident on May 17th 1893 caused the death of Peter Maddock. A group of miners were attempting to get into the pit cage to return to the surface and a crush developed. The deceased was carrying a tea can and in the struggle to embark, the can was forced into his ribs. Although none were broken, blood poisoning set in and the 35-year-old died on the 22nd. Three days after Maddock’s accident, 49-year-old Thomas Molyneux became yet another miner who was crushed to death down Sherdley, as a result of insufficient timber being set and the roof giving way.

On December 22nd 1893 William Johnson of Park Road was prosecuted for taking matches down the colliery. A fireman called James Davies was making his rounds when he smelt tobacco. He searched Johnson’s coat and found two matches in his pocket and his safety lamp was unlocked, although no tobacco could be found. Johnson - who in court said he had to travel 1600 yards underground to his place of work - denied smoking and said his lamp had become unlocked through being knocked about. Because Johnson’s coat had been searched in his absence, the magistrates chose to dismiss the charge. It was also revealed in court that miners were allowed to take pipes and matches down the mine if no gas was present.

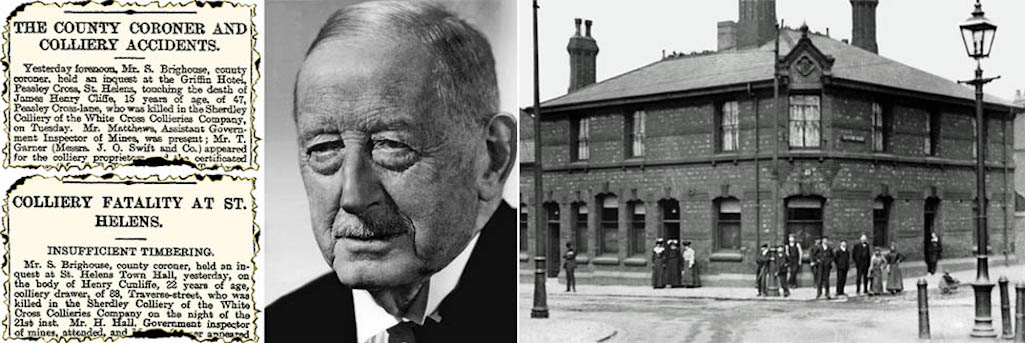

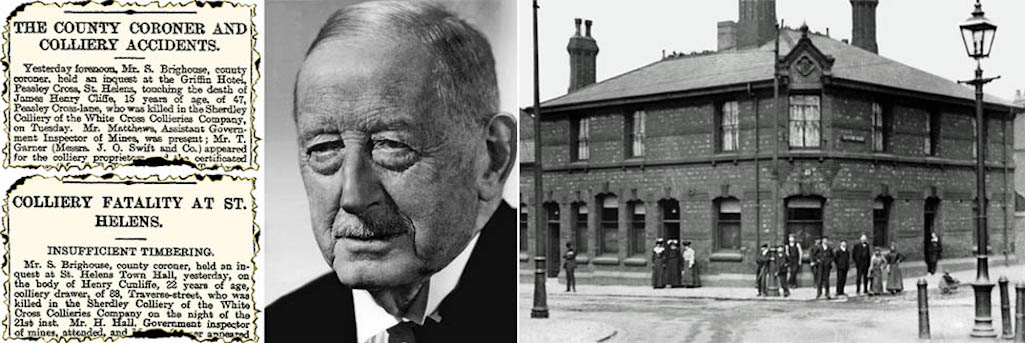

Coroner Samuel Brighouse held many of the inquests on Sherdley Colliery at the Griffin Hotel in Peasley Cross

Coroner Brighouse held many Sherdley Colliery inquests at the Griffin Inn

Coroner Brighouse and news reports

During this period over 500 men were employed at Sherdley Colliery and in August of 1894 they were thrown out of work for a couple of days by a pony boy strike. The White Cross Colleries Co. decided to cut their wages by 10%, but the lads claimed that the reduction in reality was far higher. The dispute also spread to the nearby Peasley Cross Colliery, also owned by White Cross, and 200 men there had to be laid off. After being given assurances at a meeting with their bosses held at the Ship Hotel in Raven Street, the boy strikers voted to resume work.

On September 14th 1894 a fire destroyed the Sherdley lamp room, which was situated on the pit brow. Being a wooden construction, the building had burnt down by the time the steam fire engine had arrived from St.Helens and 200 lamps were destroyed. In October Sherdley got mixed up in a bigamy scandal as a result of two employees, Margaret Anders and John Pearson, meeting at the colliery and subsequently getting married. After Pearson deserted his wife and child, she took out a summons against her husband only for his ‘other wife’ to turn up in court as well! On November 24th the 42-year-old was sentenced to two months hard labour at Liverpool Assizes.

Yet another roof fall took place down Sherdley on December 13th 1894 when James Harrison of Traverse Street in Parr was crushed to death. A large stone fell on the 50-year-old, while he was putting up pit props. Coroner Samuel Brighouse continued his campaign for mandatory timbering of pit roofs at the inquest on Henry Cunliffe, held on December 28th 1894. The 22-year-old colliery drawer, also from Traverse Street, had died when a portion of the roof collapsed on him. Fireman John Tickle and Henry Johnson – who was Cunliffe’s uncle – both gave evidence at the inquest. They told the coroner that they’d examined the workplace beforehand and were both satisfied that the supporting props and bars were perfectly safe.

However Mr. Hall, the Government inspector, told a different story. He’d examined the workplace down Sherdley Colliery after the accident and had come to the conclusion that more could have been done to make the roof more secure. In the next working place he’d found a collier working under a loose roof, which, he said, could have come down at any time. Mr. Brighouse in summing up said: “Owners ought to be compelled to look better after colliers, and colliers should be compelled to look better after themselves than they do at present.”

In February 1895 John Whitfield of Peasley Cross Lane died from injuries received during wagon shunting at Sherdley. The 30-year-old slipped after uncoupling a waggon and the wheels passed over his right leg. On April 8th a serious explosion occurred at Sherdley when five officials were surveying its main delph mine. The men were manager Robert Turner of Sherdley House, next to the mine in Peasley Cross Lane, architect and surveyor Frank Biram from Marshalls Cross Road, colliery underlooker John Harrison of Ellbess Lane and firemen Thomas Singleton and Peter Anders. All received serious burns to their head, face and arms with Biram and Harrison receiving the worst injuries. The accident was caused by a rush of gas, which had been ignited by a lamp carried by Anders, causing a sudden flash and loud explosion. This was thought to have been the first time that a gas explosion had happened at Sherdley.

Frank Biram, incidentally, went onto design a large-scale extension to Sutton National School, which was completed in late 1898. His father Benjamin Biram, of Peasley Vale House, had passed away only seven days prior to the explosion. Formerly a manager for Bournes and Robinson, Biram Snr. became managing director of the Whitecross Collieries Co. and also served as a magistrate. He was keen to improve safety in mines and designed a new type of anemometer, an instrument that measured air flow.

By May 31st 1895 manager Robert Turner had recovered sufficiently from his injuries to give evidence at the inquest on John Unsworth of Williamson Street in Parr. The 60-year-old boiler tenter (another report said 70 years) died from injuries received after stepping into a hole where an old boiler had been. On November 4th collier William Lawton of Back-Bolton Street in St.Helens was fined 5 shillings for firing a shot in part of the Sherdley mine where safety lamps were needed and where there might have been gas.

In colliery listings published in 1896, Sherdley Colliery is described as having 482 underground workers, as well as a staff of 155 on the surface. Reporting to the manager were undermanagers R. Armstrong and J. French, although Robert Turner would soon resign his managerial position to become a Consulting Mining Engineer in St.Helens. William Pattison, another experienced Durham mining engineer, who also lived at the company’s Marshall Cross Road house, replaced him at Sherdley.

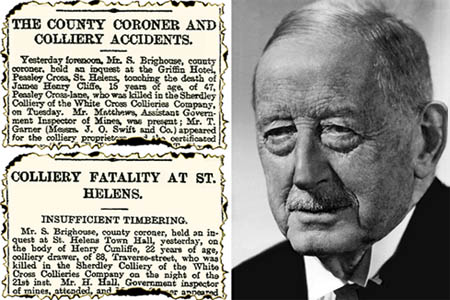

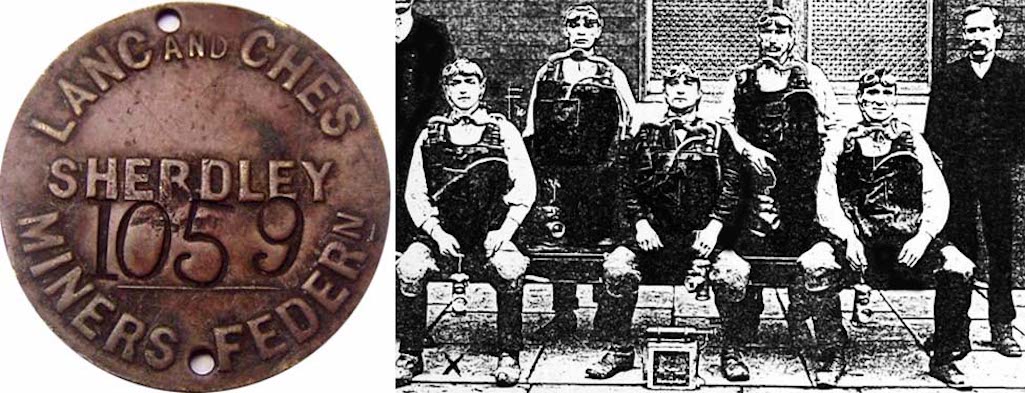

Sherdley Colliery Tally and Rescue Team - Thomas Noonan is second from the right on the back row

Left: Sherdley Colliery tally; Right: The colliery’s own rescue team

Sherdley Colliery Rescue Team

James Critchley, aged 16, was killed at Sherdley on June 4th 1897 after being run over by a ‘journey’ of wagons. Another James, James Robinson, received fatal injuries on January 13th 1898 after travelling up the haulage brow astride the rope. This suddenly sprung up, causing the 50-year-old to be thrown in front of full coal tubs on the other road. As a consequence a new rule was introduced in which the rope would be stopped while men were travelling.

There was more evidence of poor pit propping at the inquest on Francis Needham of Frederick Street, Sutton, who was killed on June 22nd 1899. The workers had left roof coal un-propped for a distance of four yards and it later collapsed upon the 47-year-old when he was filling a tub of coal. Fireman William Burnett had examined the workplace three hours earlier but had trusted the men - who were more experienced than him - to prop up the roof if they felt the need. Coroner Brighouse said: “It seemed as if the men had been left to do as they liked” and he renewed his call for “systematic timbering”.

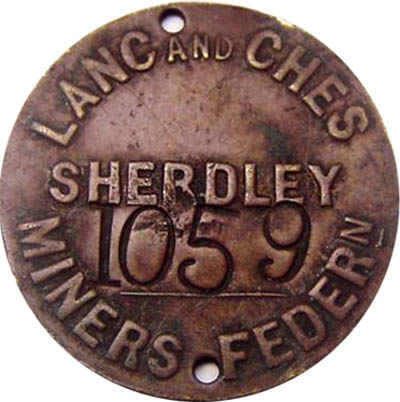

Sherdley Colliery miners tally

James Gormley was also killed by the fall of a large stone in December of that year, while bringing down some of the pit roof with a crowbar. As well as being a miner, Gormley was the licensee of the Shamrock beerhouse in Parr. Another roof fall killed 63-year-old Thomas Partington in March 1901. Coroner Sam Brighouse again criticised insufficient propping of pit roofs saying: “Something will have to be done sooner or later. If anything could be done to preserve life, it is the duty of the employer to do it.”

A shocking accident occurred to winder John Cunliffe on September 12th 1907. The 49-year-old was oiling the wheels of a pump when he fell down the pit shaft and was ‘dashed to pieces’, as one newspaper put it. On July 3rd 1911 packer Enoch Williams, aged 33, died after another pit roof fall with Thomas Battersby, aged 37, killed on September 24th 1912 by a large stone falling from the roof. The stone was reported as measuring 10 feet long by 3 feet 6 inches broad and 1 foot 3 inches thick. Another collapse at Sherdley on April 11th 1913 led to Peter Marsh, aged 24, being fatally injured by falling coal.

Wilfred Ashton’s death eight days later had some mystery to it. The 14-year-old haulage hand from Parr Mount Street had told another boy named James Price that he had a “nasty headache, and did not feel grand for work”. Later that morning Price found Ashton lying between the rails with his skull fractured, after coal wagons had passed through, although the lad told the inquest that the coal boxes hadn’t hit his friend. Henry Watkiss, aged 18, died on October 29th of the same year by a sudden fall of roof, after roof bars had been removed while a main haulage level was being enlarged.

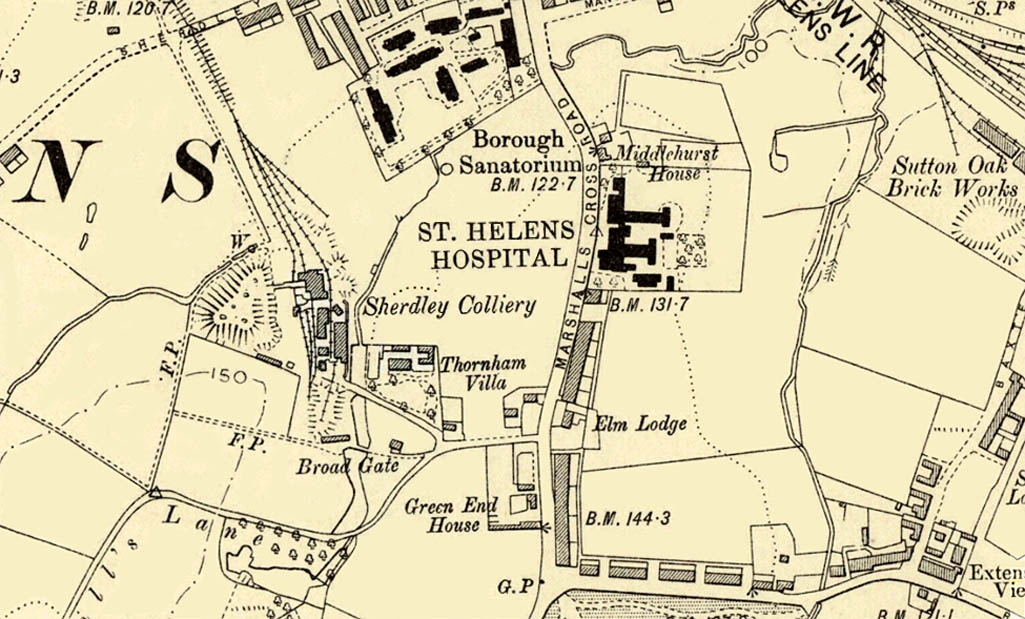

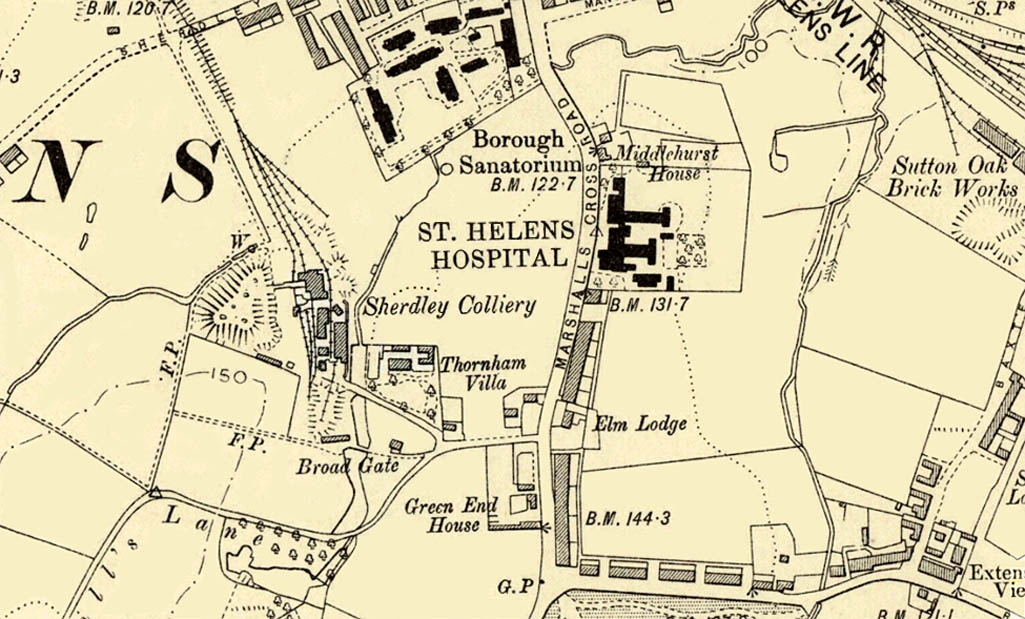

Ordnance Survey map from 1905/6 showing Sherdley Colliery with Sherdley Park to the south

1905/6 OS map showing Sherdley Colliery with Sherdley Park to the south

Ordnance Survey map from 1905/6

On March 7th 1917, 17-year-old haulage hand Paul Bannister died after being crushed while riding the coal tubs. This was firmly in breach of the colliery rules but was something that boys sometimes did. In November of that year former miner John Molyneux was awarded the V.C. for his bravery in the war. ‘Jack’ resided at 81 Sherdley Road and before the outbreak of hostilities had worked at Sherdley Colliery with his father. You can read full details of John’s award here.

Another fighter of a different kind who worked at Sherdley was boxer Mick Gordon. He was dubbed ‘The Fighting Collier’ and often journeyed to bouts after a shift down the pit. Gordon employed a well-known professional runner called Edward Forber, but after leaving the colliery Forber found himself in court. During the war miners could apply for a certificate of exemption from military service. By leaving Sherdley and gaining his livelihood exclusively from running, Forber was in breach of his exemption and an absentee from the Army reserve. His defence was that he’d been troubled by his eyesight but the court in August 1917 fined Forber 40 shillings and handed him over to a military escort.

Thomas Marsh was fatally injured on February 20th 1919 as he entered the pit cage at the end of his night shift. The 54-year-old from Peasley Cross Lane became trapped between the middle partition of the cage and the shaft bottom, seriously injuring the back of his head and neck. Marsh was brought up the pit and conveyed to St.Helens Hospital but was dead on arrival. Sherdley banksman Richard Bailey, aged 24, died on May 17th 1919, after he was crushed by a wagon. On May 17th 1919 assistant brakesman Richard Bailey was killed on the surface of the colliery after slipping off a train of coal wagons that were being taken to Pilkington’s glassworks. A colleague said Bailey was “practically cut in two across the stomach”.

On 14th August 1919 John Parry of Tickle Street in Parr was fined twenty shillings for being in possession of a pipe at Sherdley Colliery. All smoking materials were banned and workers were searched before going down the mine. Parry told the court that it was a pure accident due him changing into another coat. On June 12th 1920 at the Fleece Hotel in St Helens, a presentation was made to the manager of the colliery, William Kirk, who was leaving for a position in Yorkshire. He had spent seven years at the mine.

A 1920 share prospectus of the Sutton Heath & Lea Green Colleries Ltd. said: ‘The Sherdley Colliery is situate about one mile from St. Helen’s Station, and is connected by its own private siding with large chemical, glass, and other works, whose consumption of coal is considerably in excess of the output of this Pit.’ In Frank Bamber’s book ‘Round About The Pits’ he describes what Sherdley Colliery was like during this period:

Then on April 4th 1928 32-year-old William Ashall lost his life at Sherdley through a fall of roof coal and dirt. Fireman Thomas Littler, aged 23 of Elephant Lane, was also killed on August 16th 1929 by a fall of roof. On February 3rd 1930 three men were working on strengthening a roof down the colliery when there was a tremendous crash and the roof suddenly came down on top of them. The debris completely covered the trio, apart from a pair of clogs that jutted out from underneath. The three injured men – William Eden of Clock Face Road, William Peel of Peasley Cross Lane and John Travis of Elliot Street – were quickly extricated and rushed to St.Helens Hospital nearby.

Anderton Shearer Loader statue (pic by Galatas), union badge and disused Sherdley Colliery headgears

Anderton Shearer Loader statue, union badge & disused Sherdley headgears

Left: Anderton Shearer Loader statue; Right: Sherdley branch union badge

On August 14th 1939 Lambert Skeath, a 56-year-old pit shaftsman of Ashcoft Street, appeared in court charged with indecency, along with 41-year-old May Hanley of Albion Street, who was accused of aiding and abetting the offence. ‘Indecency’ has been a catch-all term in the past but in this context usually refers to a couple caught by the police being rather intimate, often while indulging in an extra-marital affair. Not many years earlier Skeath might well have been sent to prison for such an offence. However times were now more enlightened and so he only received a fine of 20 shillings and the shame of his name in the newspapers. Two years later on January 28th 1942, Skeath was killed at Sherdley Colliery. Formerly living in Sutton at 27 Morris Street, Lambert, like many other mineworkers, had endured a number of minor injuries during his many years at Sherdley, including a crushed toe, contused ribs and an eye injury.

At the inquest on John Swift on January 11th 1943 the coroner Cornelius Bolton said the procedure that led to the Sherdley shaftsman’s death was the maddest that he’d ever experienced. Swift from Sutton Road went down on top of a pit cage on which three oil flares were burning in order to do some work. Whilst he was attending to a pipe on the side of the shaft, Swift’s special clothing caught fire and the 52-year-old later died in hospital. Soon afterwards it was decided to close Sherdley Colliery and transfer the workers to other pits. This created much anger among the 500 men and pit-head screens women, who felt there had been a lack of consultation. A mining official was quoted by the Manchester Evening News as saying:

Painting of the Sherdley Colliery headgears made by Horace Roberts in 1957 after the mine had closed

Painting of the Sherdley Colliery headgears by Horace Roberts in 1957

Painting of Sherdley Colliery headgears