An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 70 (of 95 parts) - Memories of Sutton Part 20

Compiled by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Extracts from ‘Memories of my Youth’ by Harry Cunliffe

Phoenix House

I asked our Mary one night not long ago what memories she held of Phoenix House. She said when she was about eight years old, one night just before Xmas she was lying in my mother’s bed, the windows were covered in patterns that only Jack Frost can draw. She had been listening to the Salvation Army band playing Christmas carols and when they finished she went to the window and scratched off the frost. Peeping through, towards the shop across, all dressed up with tinsel and red crinkly paper, lanterns swinging as people went in and out of the shop, the ground reflecting the moonlight, and in the distance the sound of carols being sung by men in the street. This picture flies to her mind’s eye every Christmas time.

The house was bought and both families were found other accommodation. Our new home was at the end of a row of houses, about a mile further away from where I was born. Rather a large one by the usual standards and well constructed. We always seemed in this house to be in the country as there were fields all around us. The time we lived here was filled with happy memories. The First World War had started and perhaps seeing so many soldiers with bands playing, maybe, was the biggest reason for my being thrilled and so full of excitement. When the time came my parents made a move. We moved quite close-by, this time to an old Convent that had been converted into two houses by the simple method of fastening one door upstairs and one door downstairs, so that they could not be undone.

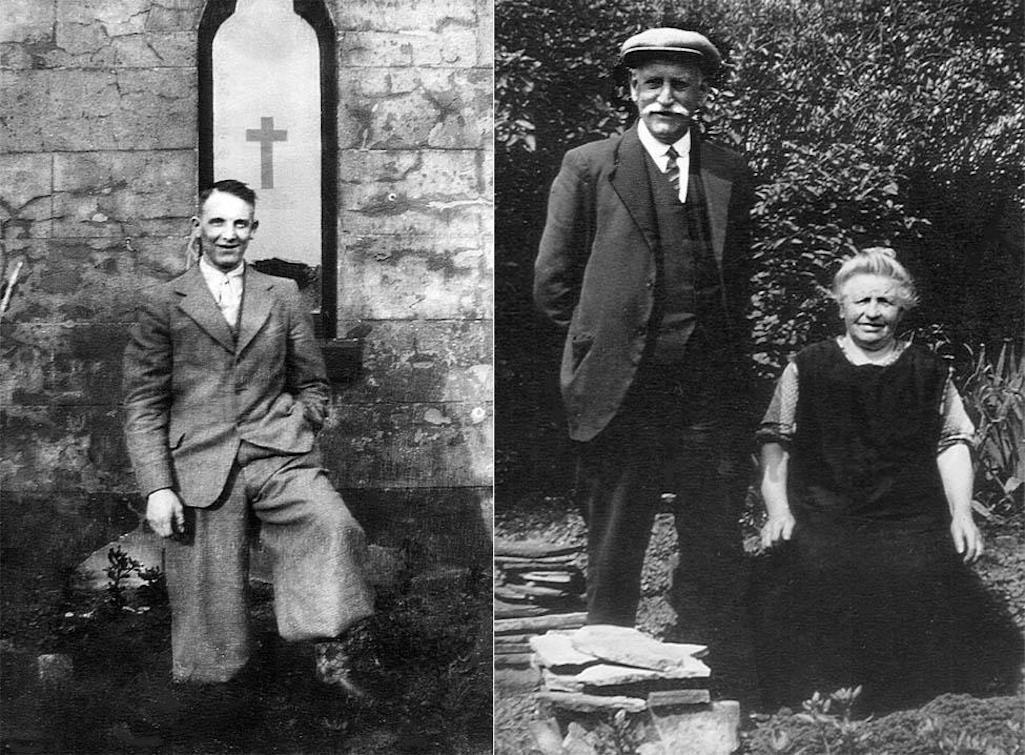

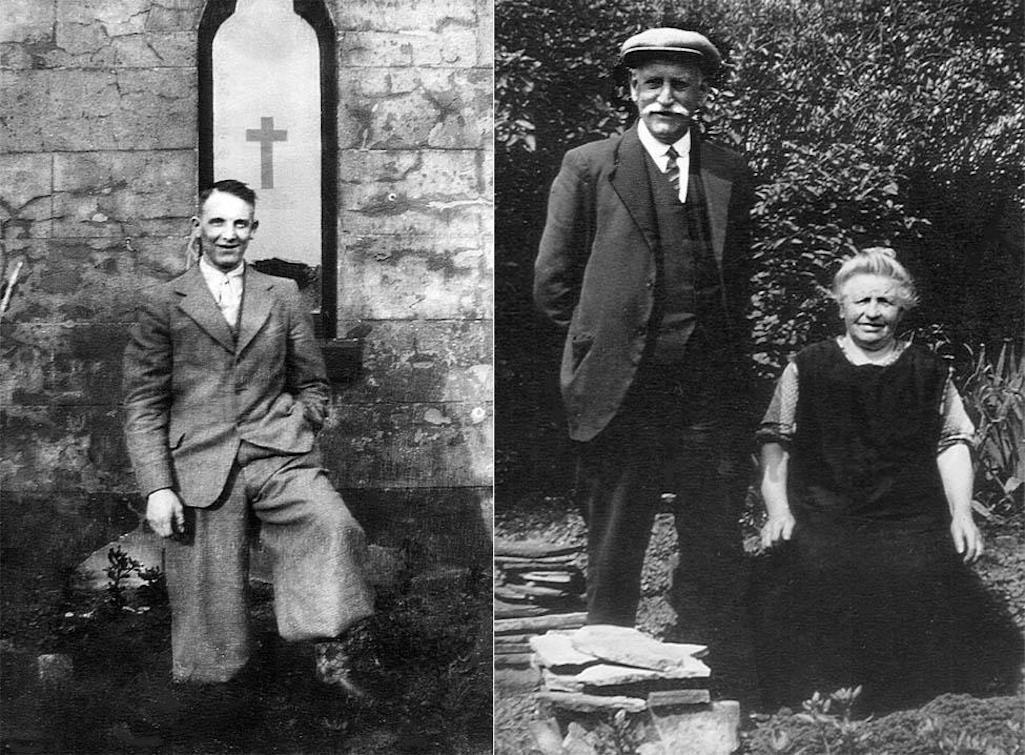

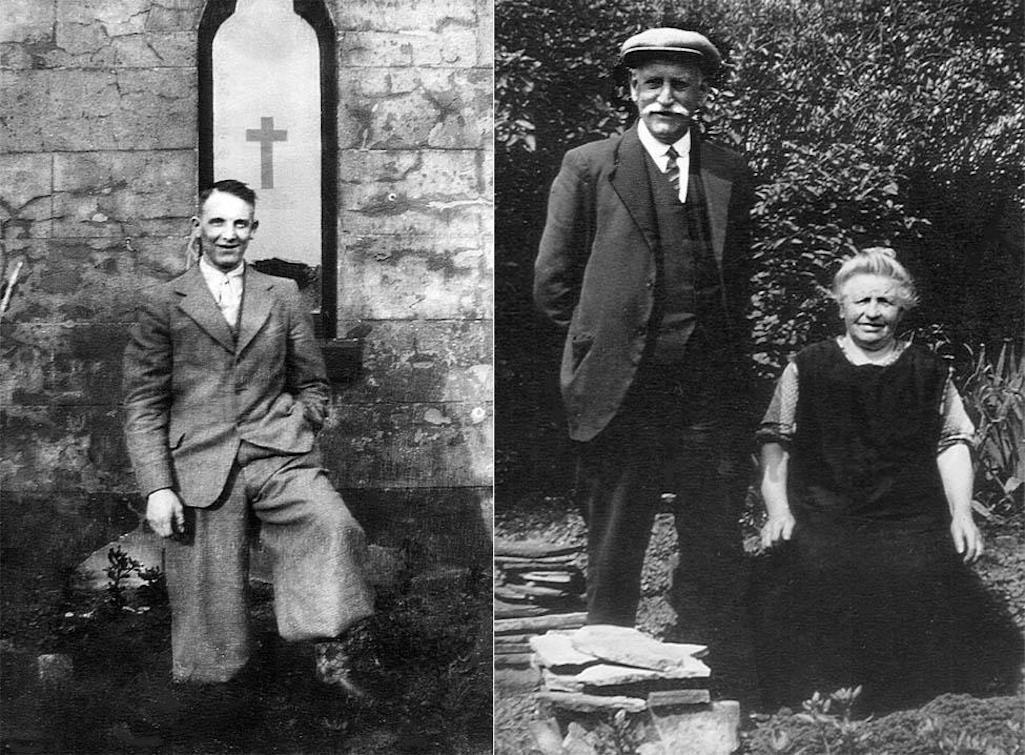

Harry’s Father and Mother

Left: Harry outside the Convent House; Right: Parents Henry and Mary Ellen - contributed by Hilary Grange

Left: Harry outside the Convent House; Right: Parents Henry and Mary Ellen

Left: Harry outside Convent House; Right: Henry and Mary Ellen Cunliffe

Drudgery for Women

Routine is a procedure but at our house without any labour saving devices it must have seemed impossible. On Monday morning all suits that had been worn on Sunday were wrapped or folded up and put away, and all soiled clothes gathered up for washing on Tuesday. All that needed steeping were put in a tub to soak till morning. When you looked at the amount there seemed enough clothes for a laundry. About eighteen best shirts, four or five union shirts, seven or eight working shirts, pit drawers working stockings, pyjamas, twenty starched collars and shirt fronts, without reckoning the girls things. They had to be washed, dolly blued, dollyed and then tortuously put through the mangle, a huge ugly big beastly contraption as ever was contrived by man’s ingenuity to enslave a woman. Millions of women suffered and were broken and died by this monstrosity.

The clothes then were pegged onto a clothes line to dry, weather permitting. If not, dried round the fire on a clothes maiden. Also get the dinner ready for when they all came in from work. That meant the small chore of peeling about nine pounds of potatoes and cooking four pounds of steak. Then there was tea and supper to follow. Imagine that! Week after week, year in, year out.

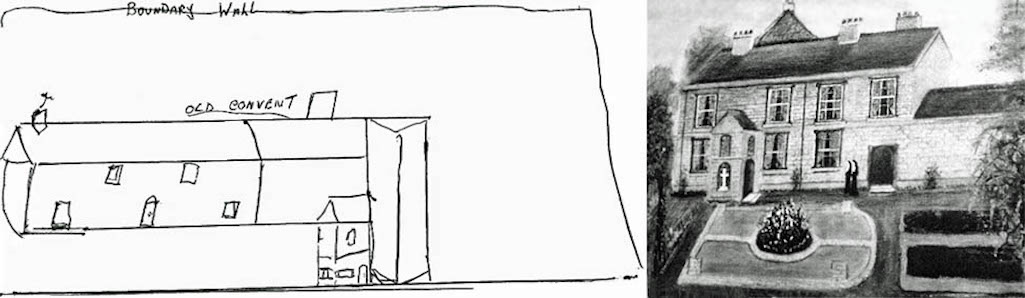

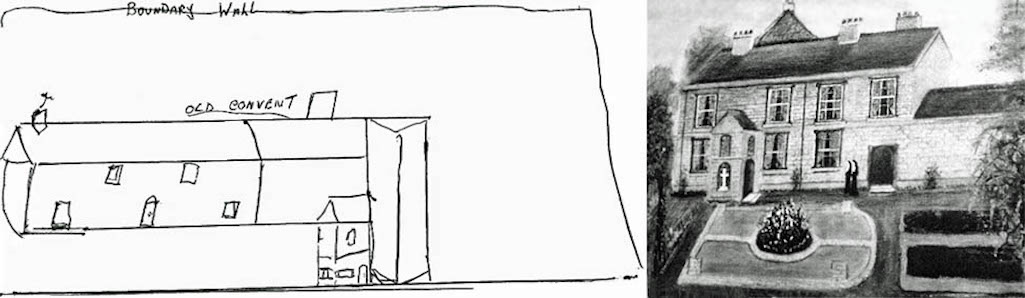

Left: Harry's rough sketch of the convent house in Fenney's Lane; Right: a late 19th century illustration of the convent

Left: Harry's sketch of the convent house in Fenney's Lane; Right: 19th century Illustration

Left: Harry's sketch of the convent house; Right: 19th century illustration

There were two gardens, a flower garden at the front and a vegetable garden on the side, which ran the full length of the Convent. These gardens were separated by a very large rockery with Lilac and Laburnum trees, which made an archway. A feature that pleased my mother was the Fernery. This was under the bathroom, which was a new addition to the old building, a necessity for the Nuns when they lived there, as I suppose there were quite a considerable number. I was led to understand that the bathroom was built for free and the Convent itself was given to the nuns for a nominal sum of one shilling a year by a Mr. Smith. The Church was called at first Smith's Chapel. Now I cannot swear all this is correct, but basically, Mr Smith was the cause of the birth of the Convent according to what Mother Superior related to my Mother. Many times while we lived there, the nuns would ask to let them bring visitors round and allow them to look through the house.

It was said that when the railway dividing the convent from the monastery was laid, a tunnel was constructed underneath the lines to enable the priests access to the convent garden from the monastery. This was supposedly bricked up prior to the nuns leaving. This convent which for so many years its walls shut out the world, except for a few girls who attended school which was in the other part, gradually gave way as a school was erected by the side of the church. In fact my auntie was taught at the convent but I think music, sewing and making lace where mostly why the girls were sent there. Of course discipline and religious instructions were a must.

After the nuns left, the rooms that for years had heard only prayers chanted, voices that spoke in low undertones, it gave way to laughter, noise and children’s constant running feet. Our family grew bigger and larger, always an organ or piano or concertina could be heard, churning out all the tunes of the times.

We were asked many many times “Was it haunted”. Did we “have a ghost” and we always said yes. Then be asked, are you not frightened. Reply, Oh no! Not now. We have got used to it. Then what kind of ghost was it, how was it dressed, where did it appear, and when, and for some reason all of us when asked would give the same reply:- It is a tall black shape like that of a man wearing a dark cloak. You cannot see his face, and you might meet in the garden or in the hall. If you did meet him in the garden you could note his manly shape and see him disappear through the wall or trees. But if you met him in the hall it was always near the bottom of the stairs, and you could not see him but would feel, or sense him, brush past you, and you would hold back your breath and stifle the need to scream, and your hair felt as if it was stood erect. Then you would be walking stiffly but quick to get into the lighted kitchen.

But like a lot of things you can say them so often that you tend to believe them. Yet this I do know, that never in the Winter has any boy or girl, or woman for that matter who visited the house, ever went upstairs on their own. They always asked someone to go with them. Imagine a small light at only one end of the hall, which when you looked along it looked miles away, and so gloomy, even deserted, and a flickering flame on the gas jet at the top of the stairs, which nearly blew out when a door opened or shut. Doors, doors, doors. Downstairs there were thirteen, upstairs there were eleven, two arches and a hall. And most of the doors upstairs had top glass panes. So if the night was windy the moans and groans of the wind throughout the house sometimes sounded like all the banshees out of hell were being let loose or holding a wake.

I was quite healthy and robust from most accounts. I suppose I can bless my parents for that, mother especially, because she fed us all well. Every week I was sent to the butchers for 14lb of shelbone, a leg of lamb, 5lb of stew, shin beef stew and a pound of suet to make a great big crust. Sometimes it would be cow heel and ox-tail, with a crust an inch and a half thick cooked in a steel dish so big you wondered how she lifted it.

There were ten of us brought up out of the fourteen my mother bore. The eldest my bother Jim was a field gunner in France in the first world war and took part in the unforgettable Battle of the Somme in 1916. After this massacre everyone proclaimed those who survived as heroes but tragically they soon forgot. Jim went back to mining. His family became bigger, then low wages, strikes etc. and soon poverty was knocking on his door. He could not understand how after millions of men lost their lives, how those who had lived through the ordeal could be forced to want. Need and poverty was their reward for their sacrifice. So later when forced on the dole, that surplus scrap heap, his dissolution, degradation, his bitterness in justice became more bitter when he had to ask for a few shillings a week from a government means test. So physically and mentally he became one of the many thousands whose spirit was crushed by poverty.

Second eldest was sister Edith, buxom woman, who worked hard on ammunitions while her husband was soldiering in France. When we, my younger brother and myself, had to get bathed on Saturday night and she had to tend to us, we didn’t play in the water. For if you did, you would go to bed with a very warm and red bottom. She never had time for any nonsense and she would scrub you as if she was scrubbing a floor.

The next eldest was my brother Walter. He was about medium height, very tough, solid, weighed about sixteen stone, fastidious dresser, quick talker, and a ponderous reader. He used to write poems for the local paper as well as writing to the press about current and local affairs or even Rugby League football, of which he was an ardent supporter. Walter was always immaculately dressed, never turned out without his Homburg felt-hat, leather gloves, spats, highly polished shoes, walking stick, silk frilled shirt, cuff-links and gold studs. He was referred to as “Sutton's millionaire” by many. His appetite for the theatre and for dancing was great. His job as a tunnel contractor down the mine provided him with a wage greatly in excess than the majority of workers. He worked hard but by golly he played hard.

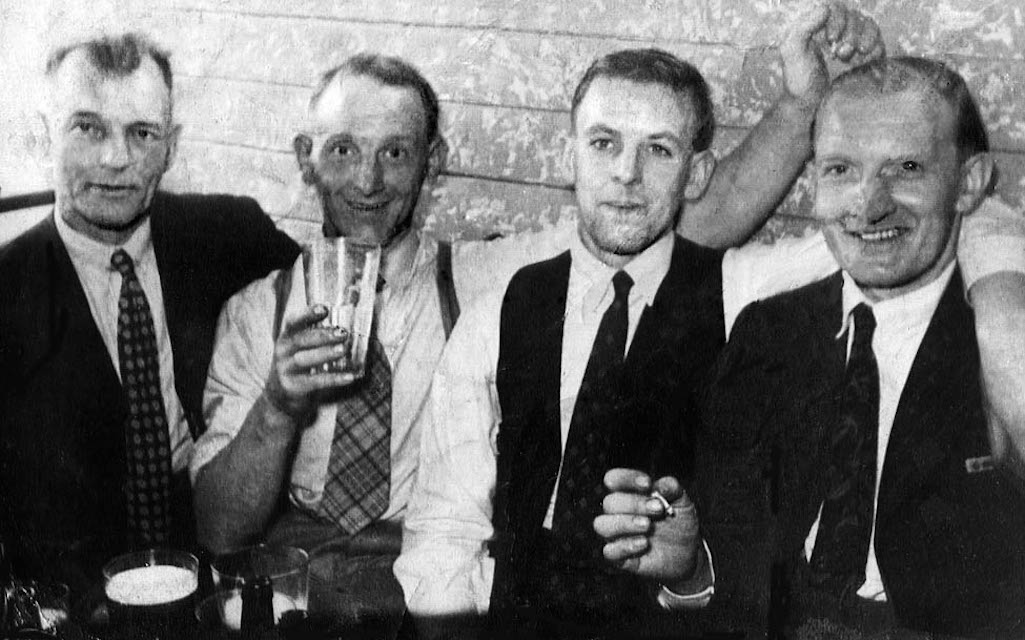

Henry and Mary Ellen Cunliffe's golden wedding party in Convent House c. 1940 - contributed by Hilary Grange

Henry and Mary Ellen Cunliffe's golden wedding party in Convent House c.1940

Henry and Mary Cunliffe's golden wedding party inside Convent House

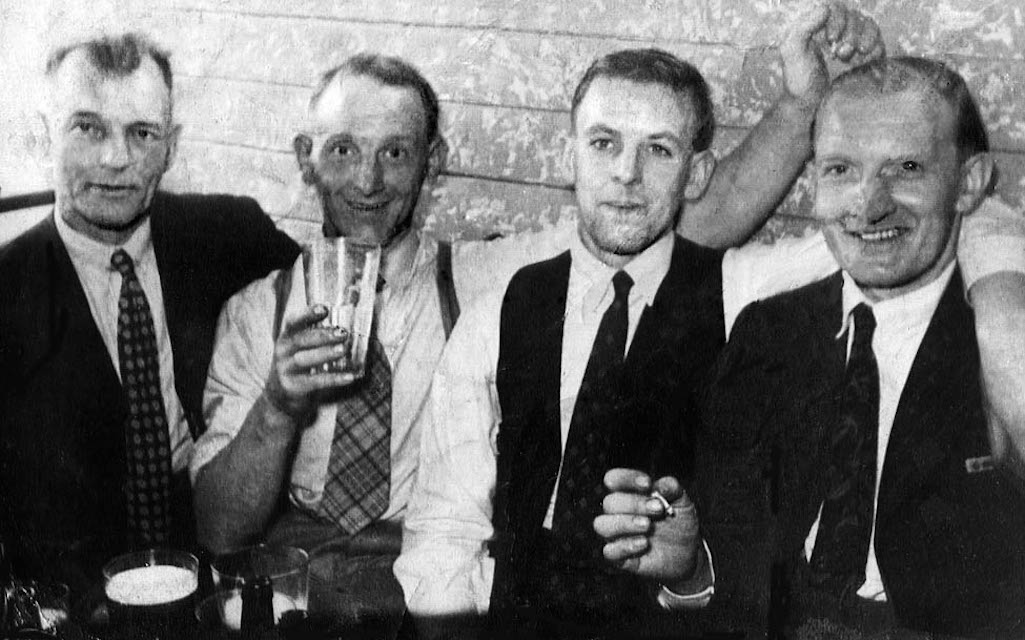

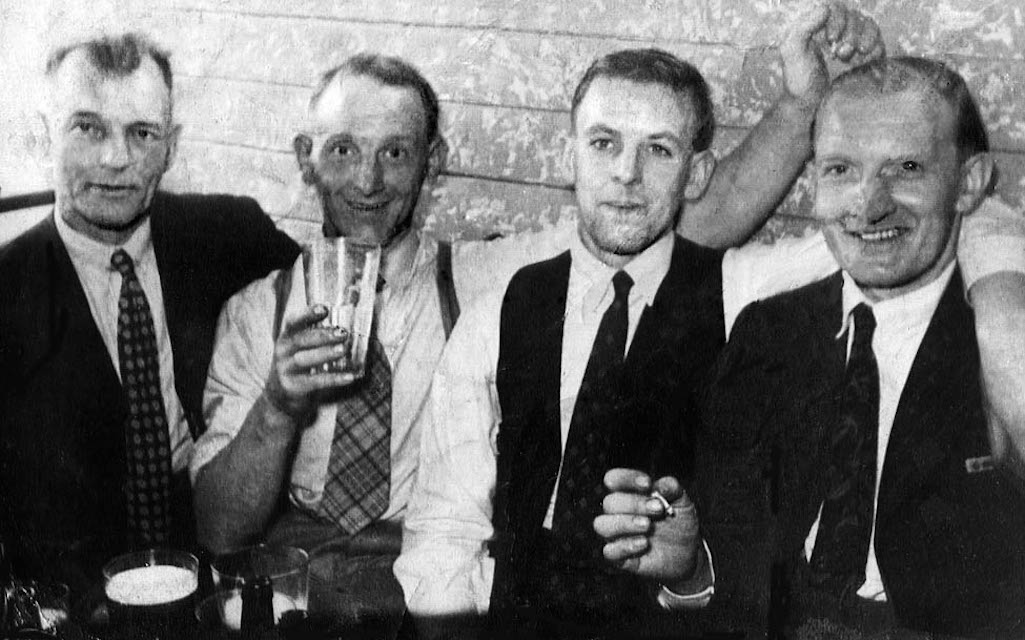

Harry Cunliffe (2nd from left) enjoying his weekly pint in a Sutton hostelry - contributed by Hilary Grange

Harry Cunliffe (2nd from left) enjoying his weekly pint in a Sutton hostelry

Harry Cunliffe (2nd from left)

We all loved reading. Father had a big bookcase that he bought from Bold Hall. It was filled with a full set of books on English literature, English history, Roman history, Greek history, set of books on Zulu wars and a large brass bound bible. There was never any need for one to be lost for something to read. My sisters loved to read but how they found time to do so, I cannot imagine.