An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 72 (of 95 parts) - Memories of Sutton Part 22

Compiled by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

‘My Apprenticeship – Some Memories Part 2’ by Ken Bailey Jnr.

On the morning of the inspection I was given a safety harness and the cage roof was levelled with the surface level of the shaft. This enabled the shafts man - who I can clearly picture but whose name I can’t recall at this time - to walk on top of the cage and attach his harness. Then it was my turn. I tried not to show my nerves and my knees knocking but maybe my face betrayed me as I walked on top of the cage and attached my harness. The Banksman signalled the winder and we began to descend at inspection speed – which is a very slow rate. This enabled the brickwork in the shaft walls and all the pipework to be viewed and visible checks made. Seeing the whole diameter of the shaft from atop of the cage as opposed to being in it, allowed me to really appreciate the engineering and get a totally different perspective of the shaft’s size and depth. Although this was routine for the shafts men, it was an experience I will never forget. Yes, those shafts men were certainly a rare breed!

Enjoying the view from a Sutton Manor Colliery headgear (From the John Oates Collection)

Enjoying the view from a Sutton Manor Colliery headgear

Enjoying the view from a headgear

Left: The Miners’ Home at Bispham, near Blackpool; Right: Borwick Hall in Lancaster (photo by Karl and Ali)

Left: Miners’ Home at Blackpool; Right: Borwick Hall in Lancaster

Blackpool Miners Home and Borwick Hall

These courses were designed to support apprentices’ personal development, collaborative working and management skills education. I recall working in small groups in problem-solving and learning how a committee would work. We also had a variety of guest speakers discussing coal industry work-related issues, such as safety, management and communication skills but also non-work related speakers talking about social skills and issues of the day. Some courses ended with a formal dinner with guest speakers. I recall one in Blackpool where the guest speaker was Peter Suddaby, the then captain of Blackpool FC. One of the topics brought up with him was whether he thought shirt sponsorship would ever be taken up! These days we are more likely to notice a plain shirt!

Borwick Hall at Lancaster was an old country house set in its own grounds. It had the facilities to do other outside activities such as archery, canoeing and hill walking. Again all this supported the underlying agenda of personal and professional development for us apprentices. I felt really lucky and appreciative to have been able to attend and be part of these residential courses. At the time you don’t fully see how these courses relate to the end job that you are training for. It is only with the passage of time that you realise how such courses fit and add to your education and enhance your overall knowledge, awareness and ability.

Colliery First Aid Team – The NCB encouraged and supported many activities via CISWO and its Area Managements. One such area was First Aid competitions. Collieries could have both senior and junior teams and we had inter-colliery competitions across the NCB Western Area including area finals, the winners of which went on to represent the area in a national final.

Sutton Manor Colliery First Aid Team L-R: Robert Griffiths; Colin Walker; Ken Bailey & John Sheriden with ‘casualty’ Mike Orchard

The first aid team: Robert Griffiths; Colin Walker; Ken Bailey & John Sheriden

Sutton Manor Colliery First Aid Team

I recall John Sheridan (Senior Overman / Undermanager), Alan Davies (Safety Officer), Rob Griffiths (Electrician) being members of the senior team and they set up a junior team which I got involved with, along with Colin Walker (Apprentice Fitter) and Mick Orchard (Apprentice Electrician). At the time of writing sadly, I cannot remember the names of the other team members. We would do training a couple of nights per week or on a Saturday morning, learning first aid and doing practice scenarios both as individuals and as a team. The senior team members were our coaches and they passed on much of their experience to us.

Besides attending our own area’s competitions, we also took part in other comps, including some in Yorkshire. We had some success and one year we won the area finals team award. Being a part of the first aid team was both interesting and enjoyable. It built confidence and the overall skills learned were transferable to real life working situations, not just first aid scenarios; it provided a framework to be methodical in assessing, planning, organising, taking action and evaluating situations and the job. But the main thing for me at the time was enjoying the experience; the lads made it so and I was chuffed to be part of it representing our colliery and being part of this wider industry network. It felt like being part of something big and important for the country.

Coal Face Training: 1977 – 1978 – This training experience lasted a total of 140 days and incorporated all the face team’s roles / jobs i.e. top and bottom pack; stable; top rip; bottom rip and powered, coal face, supports / chocks. I did a rotation of college study blocks and pit time job rotations with a Coal Face Team and New Development Tunnel Heading Team. Face trainees were allocated to a supervisor for each face job. Supervisors tended to have different approaches and communication styles but mostly led by example – a ‘watch and do’ approach.

Talking and explaining wasn’t a particular strength for some supervisors. So the need to ask a little more was important, even if it meant being the butt of the old heads’ humour. With hindsight I felt that a little more on the job verbal coaching would have enhanced the training process, building up the confidence of trainees’ more quickly and so better bridge the gap from observer to competent doer with greater efficacy. Or maybe that’s just me? I think I needed a little more time to develop and master tasks.

I admired the patience and character of a number of these skilled face-workers and tunnel men, whom I had the privilege of learning from and working with. They had a quiet honesty, dignity and humour. I think most trainees take something from those that they are supervised by and work with and I had some very good role models. These were a few of the many lessons that I learned, remembered and always looked to ensure when in my future role(s) when I had responsibility for trainees.

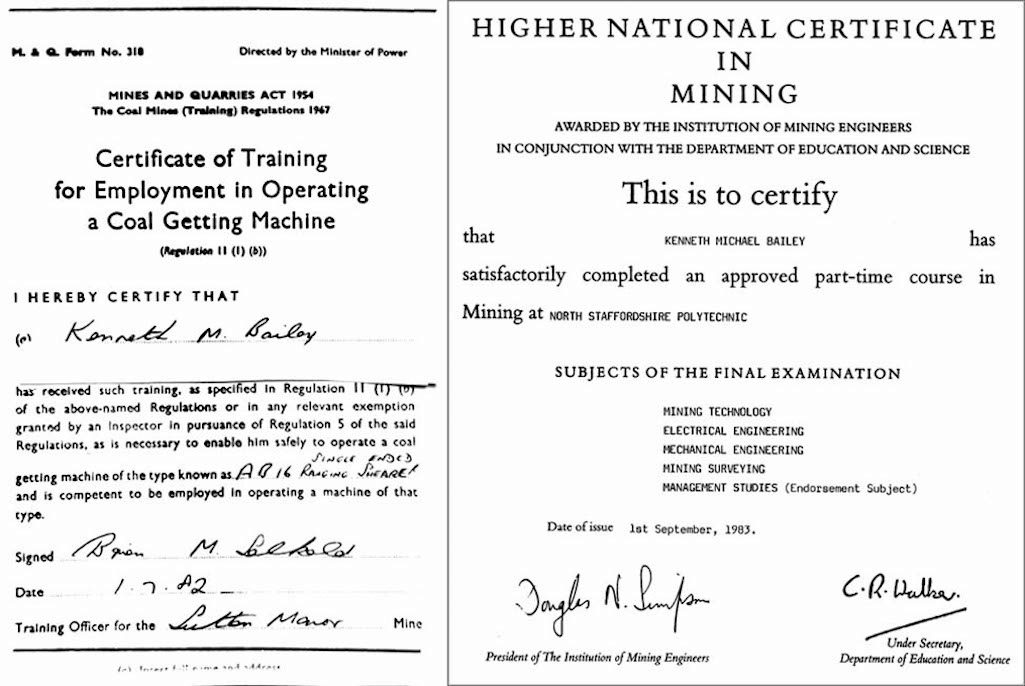

Further Education: 1980 – 1983 – Higher National Certificate (HNC) - North Staffordshire Polytechnic – Stoke-on-Trent. My three year Mining Craft Apprenticeship was completed by the summer of 1978 - however the NCB supported and encouraged its staff to continue with studies. This was a great opportunity; I did the Technicians Education Council Certificate(s) up to 1980, following which I had the opportunity to study for the Higher National Certificate (HNC).

Class photo at North Staffs Polytechnic studying for an HNC in Mining - Ken is far right on front row

Class photo at the North Staffs Polytechnic studying for the HNC

North Staffs. Polytechnic class photo

Anderton Shearer monument

What a journey! I wouldn’t describe the NCB coach as a luxury liner; it was old and seemed to have done a lot of mileage and was more of what we would call a ‘sharra-bang’! It would chug its way up and down the M6 motorway, which as now seemed continually full of traffic.

We now had new classmates with lads from the Staffordshire collieries; so new accents / dialects for both them and us to get used to. But as I’ve said previously, we could all speak ‘pit’ and it didn’t take long before we were one group. The course ran over two years and as a project within it most of us did the Ventilation Officers Certificate course, which was an important addition to our studies and training overall. I remember failing the surveying element of the course, not a great feeling at the time. I think I had gambled that certain key exam questions would be asked and they weren’t.

Anyhow in due course I did a resit and passed, thank goodness. This marked the completion of my mining academic studies. I was pleased with what I had achieved and looking back am grateful for my chances. I am sure that my life would have been very different had I not had the benefit of the NCB’s investment in training for its workforce and the opportunities that this gave me to develop.

At the end of the course there was a written exam but due to my Mining Craft Apprenticeship, I was exempt from the written theory exam parts of the course as this academic element had already been achieved. I attended the practical training and assessments of the Potential Deputies course with my good friend and college class mate Stephen Richardson. Our lives seemed to run in parallel throughout my time at Sutton Manor Colliery and I very much valued his company, support and humour.

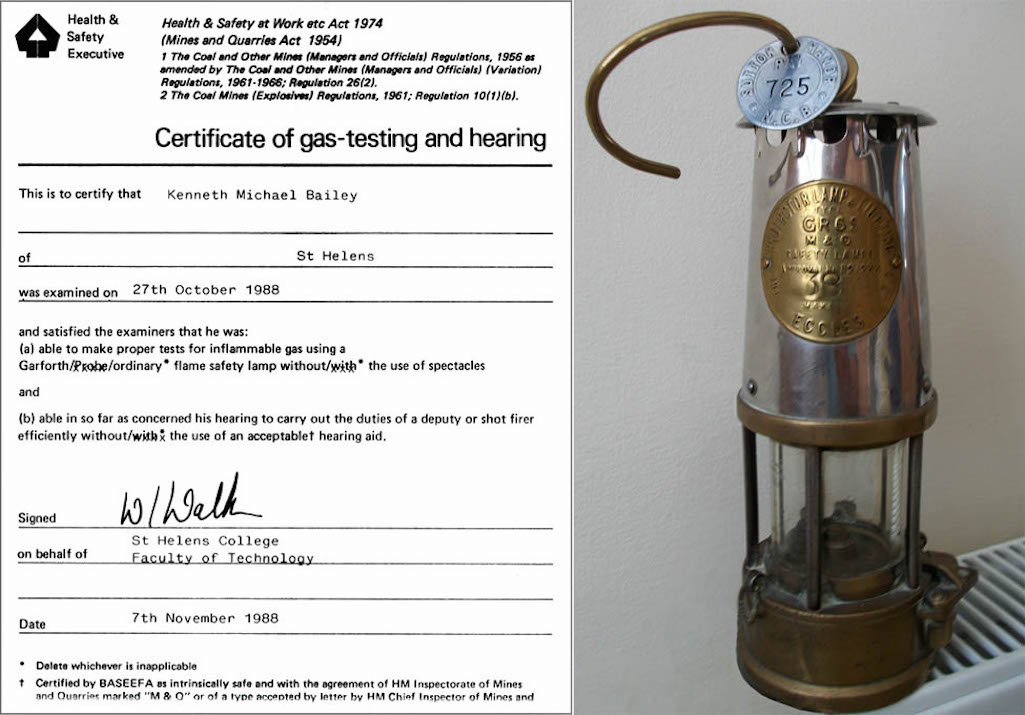

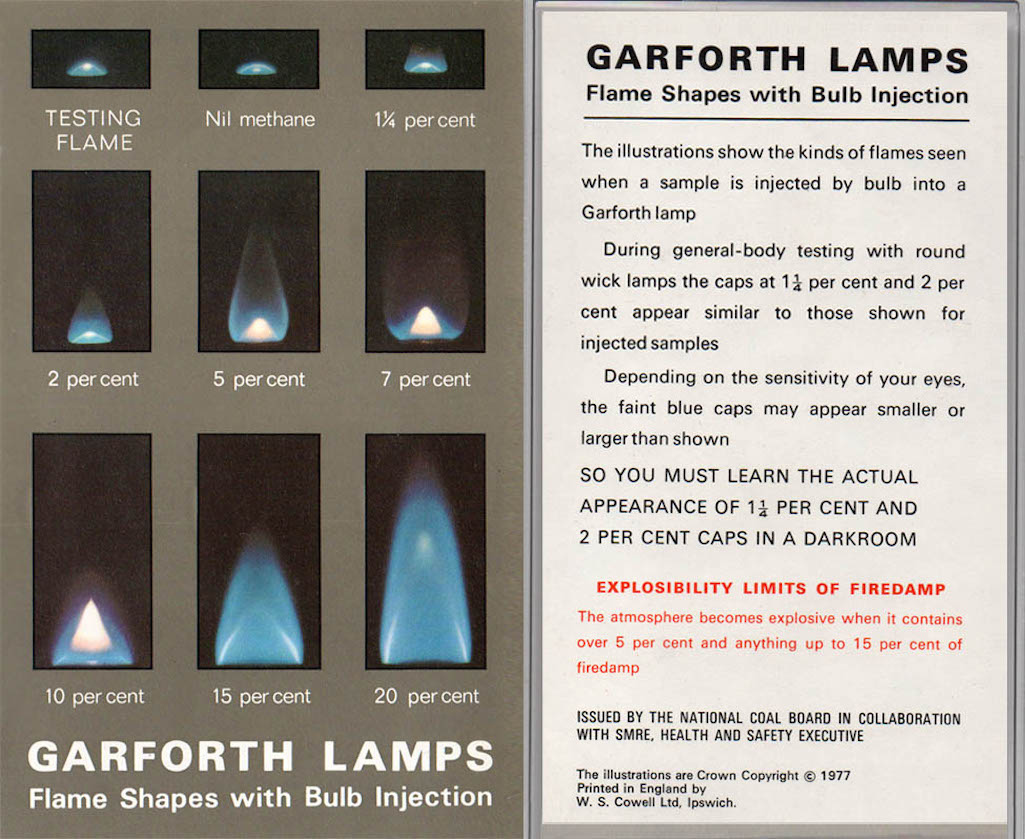

Gas Testing and Hearing – A key skill for the Colliery Deputy was the use of the Flame Safety Lamp (FSL) and the accurate testing and identification of methane (firedamp) percentages, through the recognition of the gas cap flames size and shape. This could be supported by the use of electronic methane detectors but the FSL test was the important test, as the gas cap flame would and could not lie. Colliery Deputies would test for gas when undertaking their statutory safety inspections and at any other time as required.

The priority gas caps to get right were the one and a quarter and two percents; these were the lowest ones that required immediate action to be taken if found. One and a quarter percent meant all electricity in that area / district had to be isolated and two percent meant all persons would have to be withdrawn from the district until such actions had been taken to dilute the percentage methane to safe levels. I am proud to say that I still have my FSL (shown above) which was purchased when I left Sutton Manor. I carried it on every shift during my eight and half years as a Colliery Deputy.

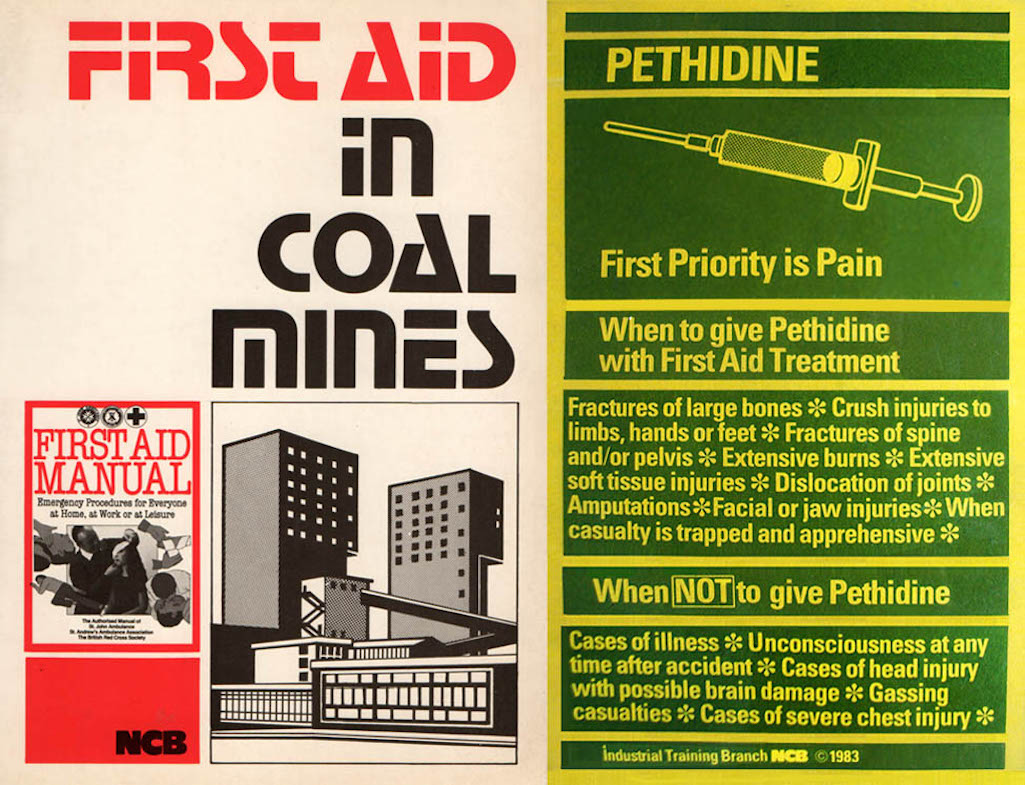

First Aid Training – I had the benefit of previously doing the first aid course but importantly for Colliery Deputies this course included the use and administration of morphine (morphia) and Entonox. Morphia was supplied in small tubes, similar to small toothpaste tubes, and had an injection needle fitted to them. All collieries had morphia available at key points underground where men worked and was stored safely in small concrete, locked safes. The Colliery Deputy in whose district it was located would check the safe contents on every shift. In later years morphia was withdrawn and replaced with pethidine. We also had ‘entonox’, a gas and air mixture. This was very useful, safe and mobile and could bring quick pain relief. Thankfully serious incidents were not as common as the lay person might imagine, but that said when a serious incident did occur it needed the best response we could give.

Underground Mines & Quarries Act Statutory H & S Inspections – Practical Assessment at Parkside Colliery – The final part of the Potential Deputies course was the mock underground district inspection and interview with the Colliery Manager. I did this at Parkside Colliery and we went to a district that had a working coal face. The manager went first and each potential deputy followed at about 15 minute intervals. We were undertaking an inspection and applying all the knowledge and experience gained not only from the Deputies course but all that gained throughout our careers to date.

There were the Health & Safety (H & S) aspects: gas testing, fire / first aid equipment, safety relating to machinery etc. There was also the awareness of what, when, where and how work was going on in the district and what materials and resources were available or needed etc. The Colliery Deputy’s role had to ensure core safety duties but to do this you needed to have your fingers on the pulse of the district, always looking to pre-empt problems or risks before they occurred.

Following completion of our mock inspection we had to be interviewed by the Colliery Manager who quite rightly could and would ask a variety of questions gauging your knowledge, understanding, awareness and organisational sense. The overall process was naturally anxiety-provoking but I feel that all the quality training and experience over the previous years came together and I passed the assessment. It was a pleasing milestone, one that I had dedicated time to and worked hard for. The next phase was to come, that of being appointed as a ‘Colliery Deputy’.

Appointed as a Colliery Deputy and Shot Firer - 14.2.83. The Deputy is appointed by statute and their duties include: In the absence of the Manager, to be in charge of the mine or district underground.

Responsible for all operations carried out i.e. organisational, supervision and control.

Make pre-shift mine inspections with particular regard to Health & Safety.

Undertake duties of an official superior as required.

Fire rounds and shots using exploders and detonators.

As a qualified First Aider, responsible for carrying First Aid equipment.

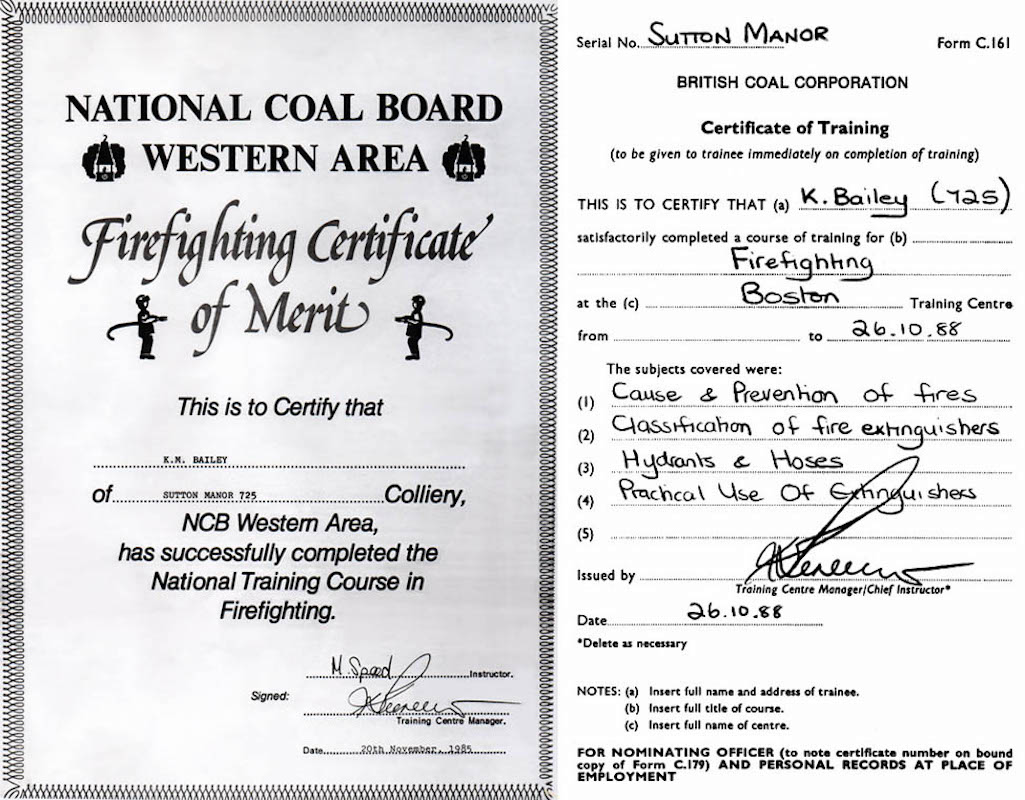

National Training Course in Firefighting in November 1985

Certificate of Training in Firefighting at the Old Boston Training Centre in October 1988

Between 1983 and 1986 I was a Deputy on the W21 Face. From 1986 – 1988 a Deputy on the H24’s Face Development; then H24’s Face Deputy and from 1989 – 1991 H27’s Face Deputy.

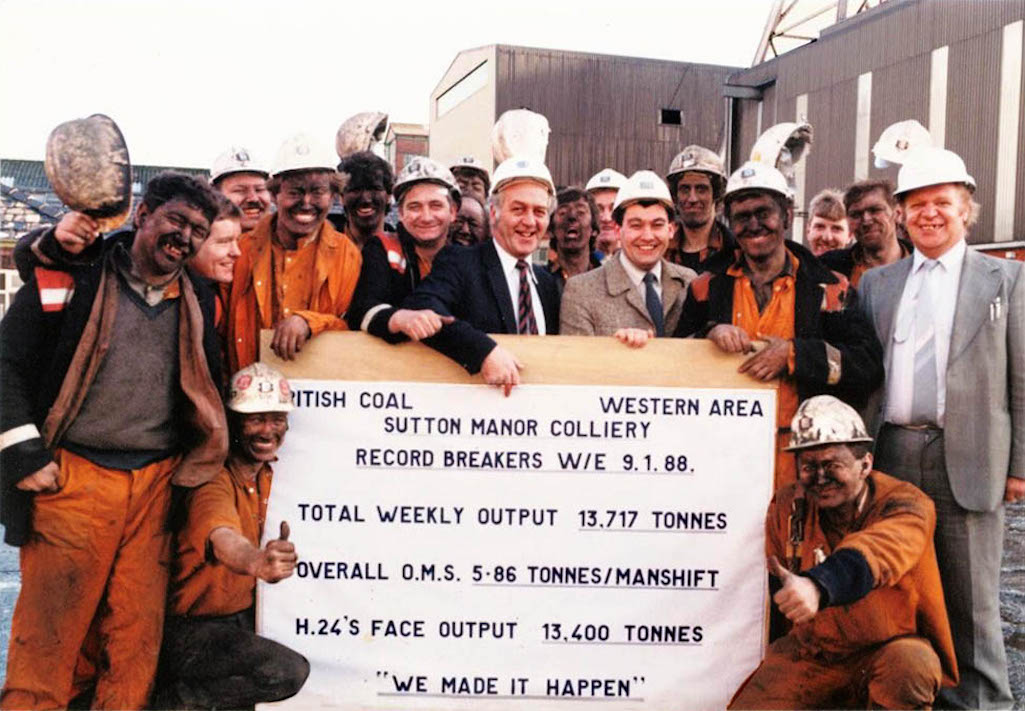

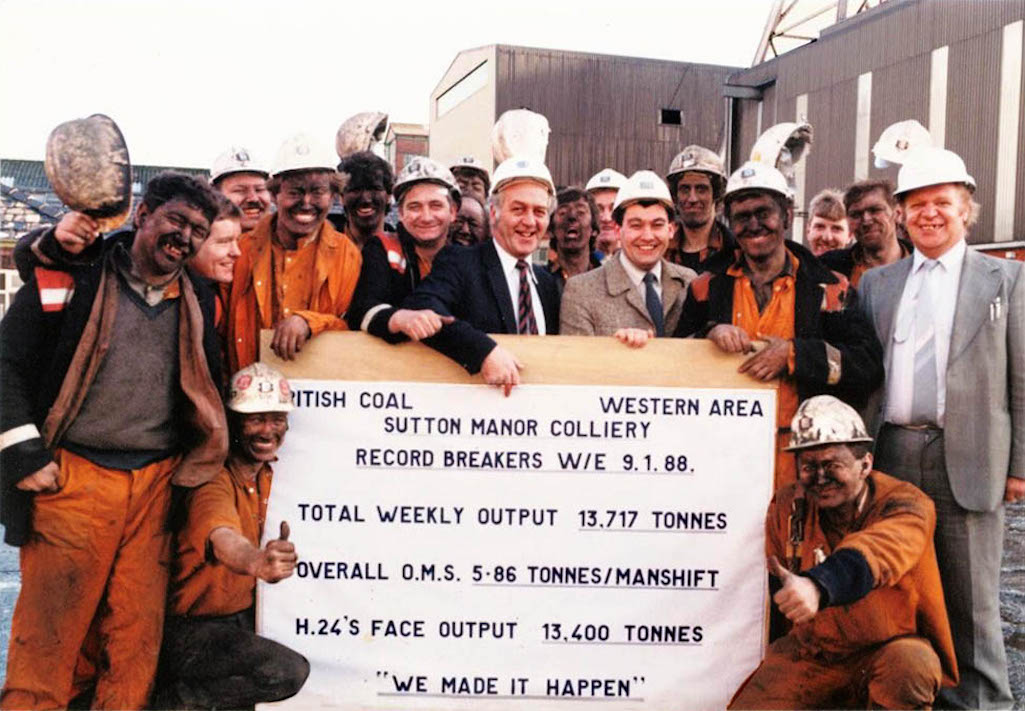

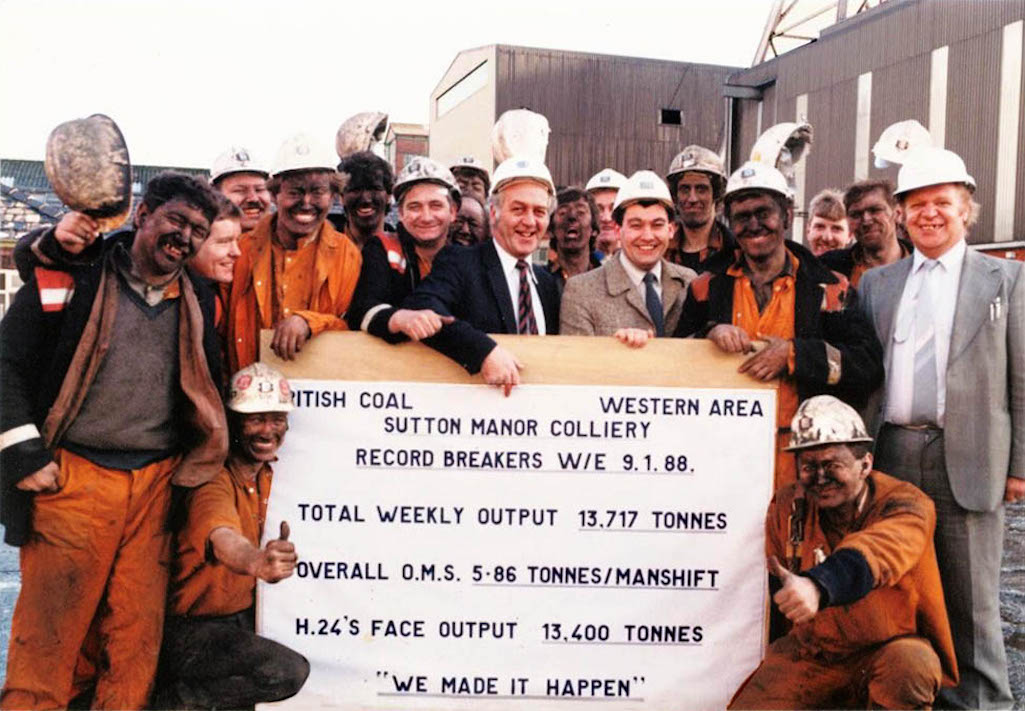

Working at Sutton Manor Colliery on the H24 coal face on which Ken Bailey was a deputy

The H24 face at Sutton Manor on which Ken Bailey served as a deputy

Working on the H24 coal face

There had to be a conscientious, diligent approach and there could be no negotiation on issues of safety. The managerial part was very visible; as a colliery official, booking men’s presence and allowances in time-books, giving briefings on work, safety issues and requirements, organising, delegating priorities, supervising jobs, ensuring safe practices and adherence to working rules / protocols.

Ken Bailey’s NACODS badges, shot-firing key and tool commonly known as a ‘pricking tool’

Ken’s NACODS badges and shot-firing key / pricking tool

Ken’s NACODS badges and shotfirer tool

Thoughts – With the passage of time it can be easy to have and give an over romanticised view; real life memories need to keep a balance of positives and negatives. There were some difficult and challenging times - the role had significant responsibility and accountability. Not everyone viewed work, you or your role in the same way. There were periods when some senior management viewed you as the enemy and out of sight treated you as such, particularly us younger deputies. At times you could find yourself being in what I called the ‘lonely place’, in-between the work team and the Manager. Some might say that was character building; well maybe, there were certainly lessons learnt about myself and others that influenced and informed the rest of my working life. That said though; the predominant memories I have are positive.

The Chances – The NCB, a great British nationalised industry, gave me, a lad who left comprehensive school with very average Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) grades in Mathematics and English, a real chance to progress. The notion of a nationalised industry seems a thing of the past, but it was from such an enterprise that I was given real employment and the opportunity to develop my potential through a technical education and training programme and along with many others, I believe became a working asset for our community, our working culture and indeed our working nation. It doesn’t seem the same for the younger generation of today.

Maybe a new form of nationalisation public-private sector partnership model may develop, employing and providing for the tier of our workforce population whose skills and qualities are best brought to the fore via practical and technical education programmes. It feels to me that the laudable focus on university level education has inadvertently sidelined that significant percentage of our workforce who can best serve through technical training and education.

I wonder what this sounds like to both today’s and future readers. I don’t know if I am able to convey my meaning and context in these few words. It’s not necessarily a political message. For me it’s about a belief in supporting and promoting working opportunities, service, communities, work ethic, camaraderies, friendship and pride. The characters – good, bad and ugly, lads and men – that I met and listened to, learned from, their life knowledge, differing outlooks, experience, patience, kindness, daft humour and banter all influenced and developed the person that I became.

Ken Bailey is kneeling on the right of this Record Breakers photo from January 1988 giving the thumbs up

Ken Bailey is shown kneeling on the right and giving the thumbs up

Ken Bailey is kneeling on the right

However the government’s national pit closure programme finally caught up with Sutton Manor Colliery and in March 1991 it was announced that coal production would cease and the colliery would close subject to any review process. I clearly remember my last working shift on Friday 20th September 1991. I was deployed to the Pit Bottom district, I think to give me a relatively simple shift for a last day. However one of Her Majesty’s’ Inspectorate (HMI) of Mines & Quarries turned up, so it wasn’t so simple a shift after all! The following week I used the last of my holiday entitlement and left the industry on Friday 27th September 1991.

My understanding is that when I began my mining career in 1975 Britain had approximately 240 collieries and when I left sixteen and a half years later there were 60+ working collieries left and now deep coal mining in the UK is consigned to history.

In March 1975 I thought I had a job for life, but it was not to be, so I had to start afresh and begin a new career. I attended my first day at Liverpool John Moore’s University on Monday 30th September 1991 as a student mental health nurse, back in school and with NHS clinical job rotations for 3 years, with my mining education, work and life experience(s) standing me in good stead throughout.