An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 56 (of 96 parts) - Memories of Sutton Part 6

Compiled by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXXII

'Life in the Old Convent Part 1' - Extracts from 'Once Around the Circuit' by Dave Latham

'Life in the Old Convent Part 1' - by Dave Latham

'Life in the Old Convent Part 1' - by Dave Latham

The rent was £6 per week and for that we had a 16-bedroom house, a huge kitchen with bread ovens, a washhouse and a “two holer” outside toilet. In addition there was a three-storey house once used by the Mother Superior which my canny Great Grandmother sub-let for £10 a week to an American from Burtonwood Air Base, who we called Whirly Gig for some obscure reason.

The American family had one son called Larry who was older than the rest of our gang. Our gang consisted of numerous nephews and nieces who lived in the house that my Great-grandmother rented. Great Gran, as we all called her, had sub-let the numerous rooms in the old convent to her many sons and daughters who had married and were waiting their turn for a council house to become available. During the war most of the men were away “doing their bit for King and country” and so it was ideal for the wives and subsequent children to live in this wonderful family community.

3-year-old David in Woolworths, St.Helens unhappy at being asked to pose with an empty box on the lap of a sad Santa!

Three-year-old David in Woolworths, St.Helens on the lap of a sad Santa!

3-year-old David in Woolworths in St.Helens on the lap of a sad Santa!

By 6.30am, Pa was on his way to work with all the other miners with his “snap can” and bottle of tea in his knapsack and I would lie in bed and listen to the sound of the miners' clogs on the cobble streets as they walked or cycled to work. When Pa came home from the pit he would be black from head to toe with coal dust. Great Gran would make him take off his jacket, trousers and wooden clogs outside, whatever the weather and he would settle in front of the cooking range in the kitchen clad in an old dressing gown. Spitting into the flames he would say; “just clearing the dust out of my lungs mother” and light up his pipe. We kids knew to stay out of his way until he had “settled down” after his day’s hard labour.

Eventually after bringing each other up to date with the “local news”, Great Gran and Pa would allow us kids to congregate round the fire. Great Gran was a wonderful cook and the smell of her cooking would drive us mad. We looked forward to her Lancashire hot pot, pea and ham soup with home made bread and “best” butter, Lobbies (a wonderful variation on hot pot) which was also known as a pan of “scouse” and grated cakes made from grated potato, flour and milk. All very cheap but nourishing meals. If we were lucky we could expect rice pudding or spotted dick for afters and we would fight over who got the burnt bits off the rice pudding and who scraped the dish.

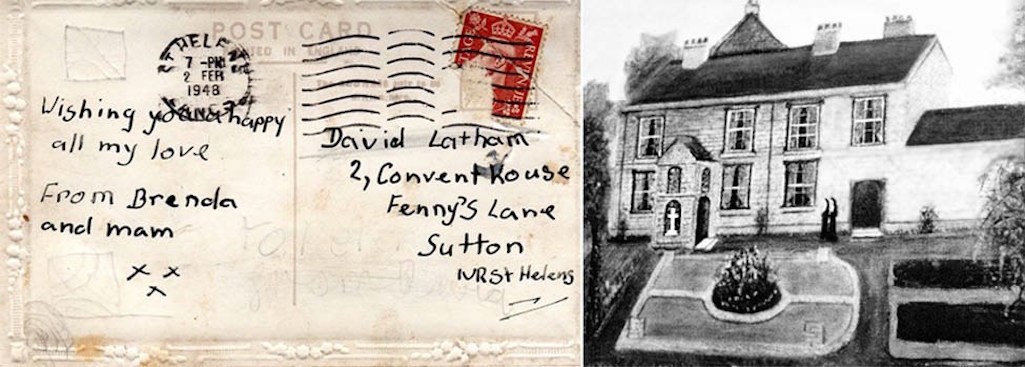

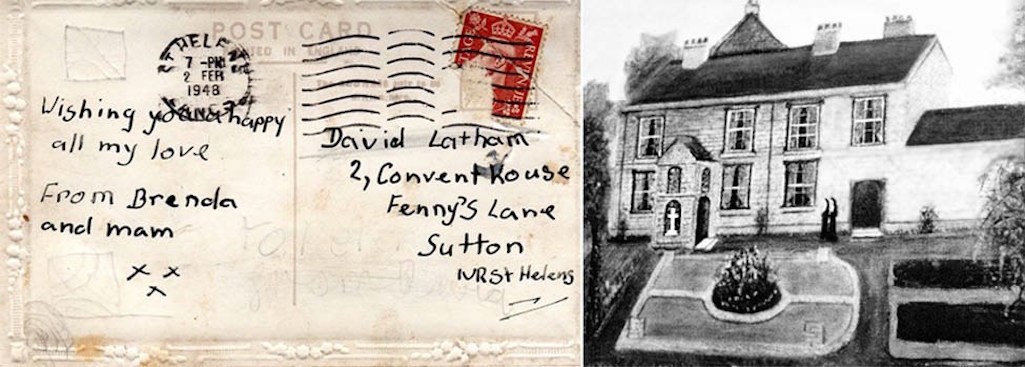

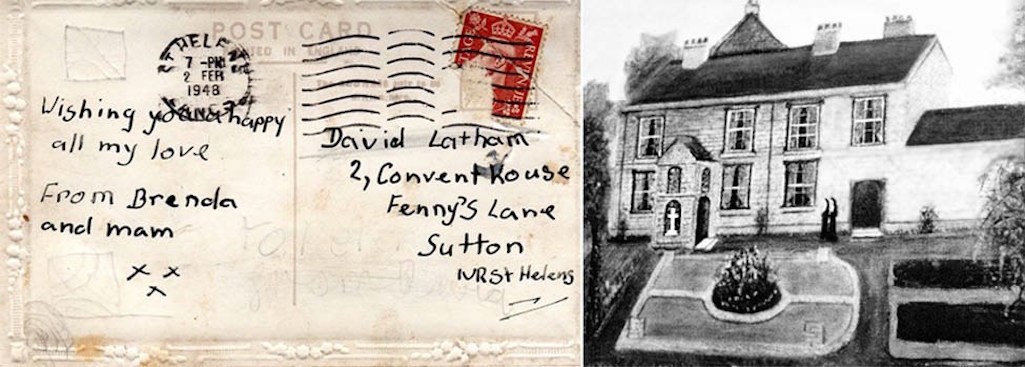

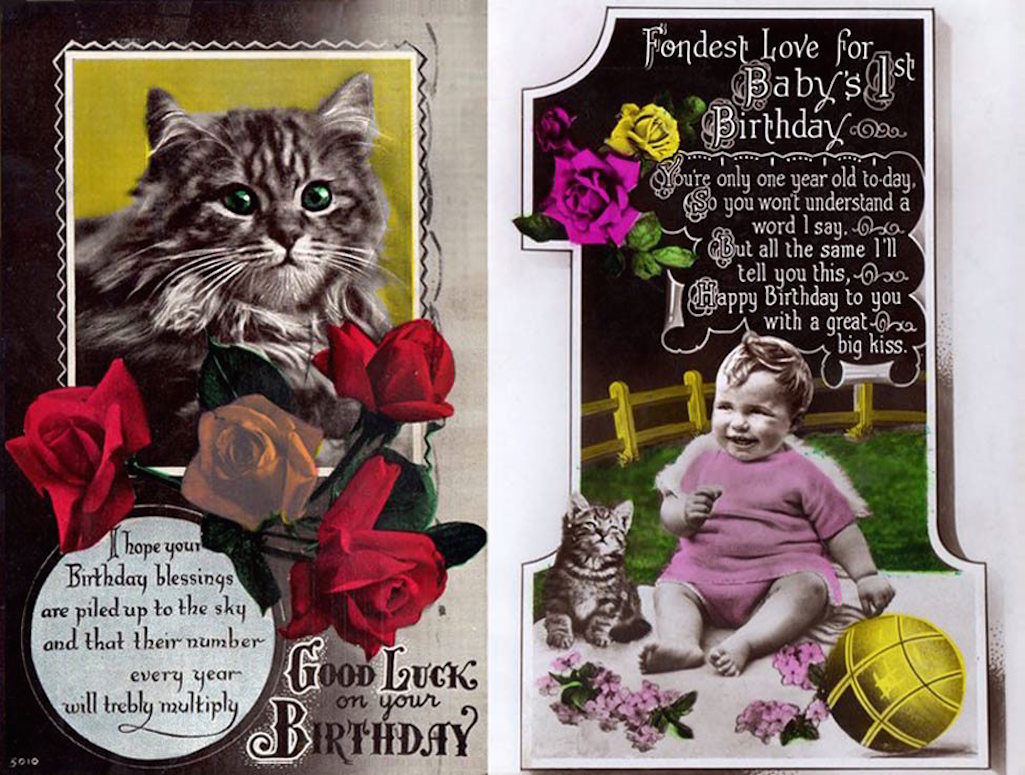

Left: Birthday postcard sent to David at the old Sutton Convent; Right: 19th century illustration of the convent

Birthday postcard sent to David at the old convent and an illustration of it

Birthday postcard & convent illustration

Then he, my Great Gran, my mum and dad, aunts and uncles, and sometimes a gaggle of kids would set off either to the Sutton Bug (the local cinema) or occasionally the miners club where we would be in place by 6.30 pm to secure our seats. At the miners club (kids were allowed in a back room as long as we behaved) the evening would be spent playing Bingo, the men drinking Greenalls or Walkers bitter.

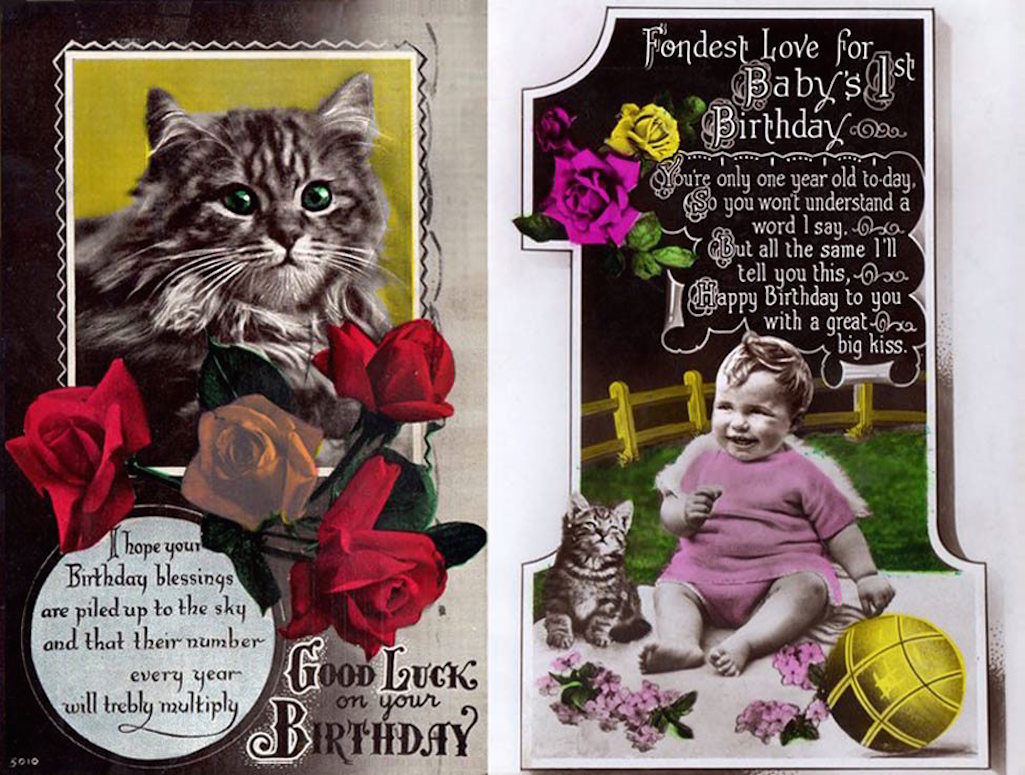

Two birthday cards sent to young David at the Fenny's Lane old convent house - contributed by Dave Latham

Two birthday cards sent to young David at the Fenny's Lane old convent house

Two birthday cards sent to young David at the Fenny's Lane convent house

Sutton Nash c.1953 with teacher Miss Woodward and David Latham in the middle with his shirt collar out

Sutton Nash c.1953 with Miss Woodward and David in the middle with shirt collar out

Sutton ‘Nash’ class photo c.1953

I honestly never realised what we were doing was illegal, I was after all only about 6 and I genuinely thought this was how everyone got their coal! On one particularly dark and windy night, Great Granddad proclaimed that we had better get the coal stock in. After supper we all donned our dirty clothes and collecting our barrows set off for the “liberation”. My job was to wait at the end of the entry, my cousin Tommy was at the other end and we were to whistle if anyone walked along the path or if we spotted any railway worker through the gaps in the sleepers. In the year I had been on “guard duty”, I had never seen anyone so I guess I had become complacent! When Tommy and I gave my uncle Wilf the all clear, Wilf and my dad would clamber up the sleepers and Wilf would jump into the nearest wagon whilst dad would sit astride the top of the sleepers.

Wilf would pass the huge lumps of coal each weighing up to 20 lbs to dad who would drop them onto an old mattress kept for that one purpose behind our garden wall to deaden the sound and stop the coal from splintering. Teams of uncles and aunts would then barrow the coal like an army of ants back into our garden ready to be broken up for burning. The whole operation would take less than an hour, Dad and Wilf slowly moving along the carriages so as not to empty any one wagon too much. One night, no one spotted the wheel tapper who instead of walking down the line approached us by walking and crawling underneath the wagons, the swine! By the time he was spotted by Tommy, it was too late for dad and Wilf to climb down and get back into the house. We all hid as best we could in the shadows and my father and uncle crouched down on top of the coal in the wagon. The next thing we heard was the guard’s whistle and then the “Phuff Phuff Phuff” of the engine getting up steam.

The wheel tapper stood his ground not knowing that our loved ones were about to be shunted off into the darkness on some long and cold journey. Slowly the train disappeared into the distance quickly getting up speed. Nothing had ever happened like this before, even Great Granddad was “flummoxed” my mother and aunty Margaret cried and I, convinced that I would never see my father again, joined in. It was in the middle of the night that the two returned, filthy dirty, apparently only their eyes and tongues being any colour other than black. I was asleep at the time but the next morning both dad and Wilf had been cleaned up sufficiently and gone to work by the time I awoke.

Later that evening, we all sat round the blazing fire fuelled by the liberated coal, as dad and Wilf recounted the story of their adventure, the train finally had stopped at a level crossing near Warrington some ten miles away, allowing the two brothers to jump off the wagon. After walking to Newton Le Willows they had got a lift in a fish van. How we all laughed as we tucked into Haddock and chips, a present from the fish van driver who said it was the funniest tale he had heard for ages.

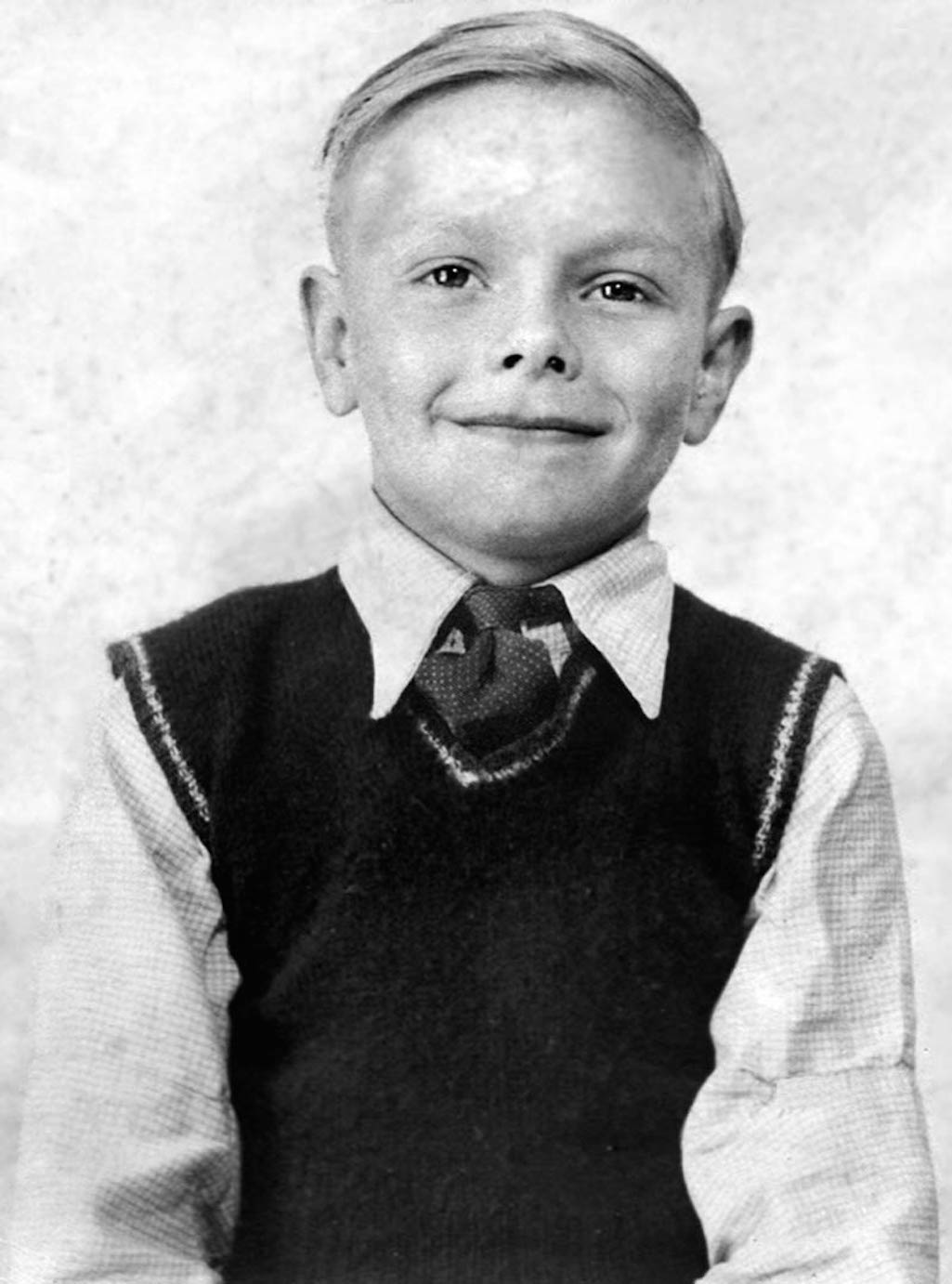

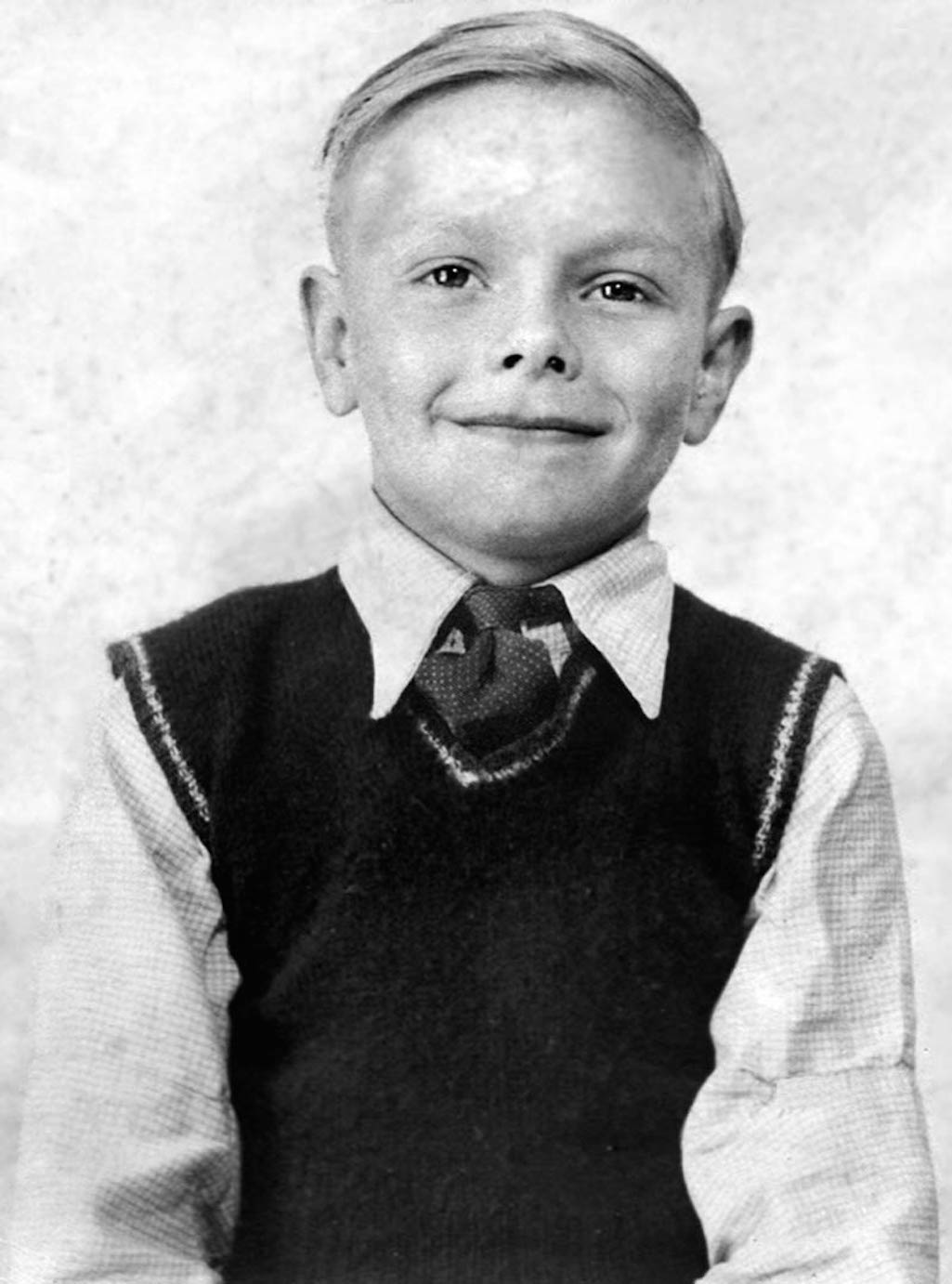

David Latham - "He cleaned up well!" - picture and caption contributed by Dave Latham

David Latham - "He cleaned up well!" - picture and caption by Dave Latham

Photo of young David Latham

I often accompanied Pa for a walk into Sutton to replenish his pipe tobacco. Many was the time that I had to stand guard over a steaming pile of horse muck when Pa would rush off for a suitable container to carry home the trophy for his “muck heap”. I have even heard him argue with other gardeners who laid claim to whichever horse had provided the treasure. Pa seemed to have exclusive rights to the coal man’s and the rag and bone man’s horses’ waste products. It was a standing joke amongst the family that Pa would actually charge great Gran for his home-grown produce. Great Gran ran the house finances with a discipline that would have shamed any Chancellor of the Exchequer that had lived at number eleven Downing Street.

In fact as strange as it seemed Pa charging Great Gran for his produce helped balance the books. Food was included into her “rent” charged to each family residing at the house. All the wives “mucked in” with the preparation and cooking but the shopping was organised by Great Gran. She also sold any surplus vegetables to the "stink shop" in Sutton, some being exchanged for bruised or slightly rotting vegetables which would go into stew or soup. The “stink shop” was a very apt name for Mr Robins's vegetable shop as he also sold fresh fish on Fridays. No one including Mr. Robins seemed to take any offence at the shop being called the Stink Shop.

Next door to the stink shop was the Coop or Royle's, as it was known in Sutton. Royle's was a cut above all the other shops in the village, smart men and ladies in white aprons met and served their customers with a long lost reverence. I can still remember my mum’s Coop divi number 29370 as it was drummed into me to give to the shop assistant so we could claim our annual dividend. The smell of tea and coffee and boiled ham mingled with the clean sawdust on the floor and the Brasso used each morning to clean the brass door furniture and other gleaming counter rails.

If we were flush with money my mother or Great Gran would allow us to indulge in a half pound of broken biscuits, beautifully wrapped in a conical bag made individually for every purchase out of blue sugar paper. These bags were saved and used for other treats like a bag of chips if we were allowed to eat and play outside. Somehow, salt, vinegar, sugar and chips seemed to taste wonderful in those far off days. My idea of heaven was a “Connie onnie buttie” made with Nestles condensed milk spread on a thick crust of Great Gran's bread. Connie onnie had various other applications; my father often used it to stick wall tiles to the fireplace!

One November Larry, the American in the three storey house, paid us boys two shillings each to “liberate” some fog detonators from a signal box in the Pudding Bag. We stole a box of twenty-four detonators each about two inches in diameter. We had used previous stolen detonators with great effect to “attack” rival gangs' bonfires on Guy Fawkes nights. Using catapults to accurately place the detonators into their fires from a suitable distance, the resulting explosions and firestorms caused the early end to the rival’s jollity.

Larry had planned to use the 24 detonators to make one BIG explosion and the noise generated by Guy Fawkes Night would hide the bang he planned. Sadly the first detonator that Larry tried to prise open with a screwdriver exploded and blew off three of his fingers. Mercifully his eyesight was not lost, though, he claimed he could hear church bells for hours afterwards. Thank God none of the other detonators exploded or Larry, son of Whirly Gig would have been another casualty of friendly fire before it became a standard American war term.

We had heard the explosion from Great Gran's house, we boys were worried sick that Larry would implicate us in his experiment, but thank God, he didn’t. Not that we were worried about the Railway police, the American Air Force or the British Constabulary, it was the thoughts of what our fathers and Pa would have done to us that petrified us. God Bless you Larry wherever you are!