An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 86 (of 95 parts) - Sutton Manor Colliery Part 1 (1906 - 1959)

Lea Green Colliery | Bold Colliery Part 1 | Clock Face Colliery

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me

Sutton Mineworking | Lea Green Colliery

Clock Face Colliery | Bold Colliery Part 1

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Old Sutton in St Helens

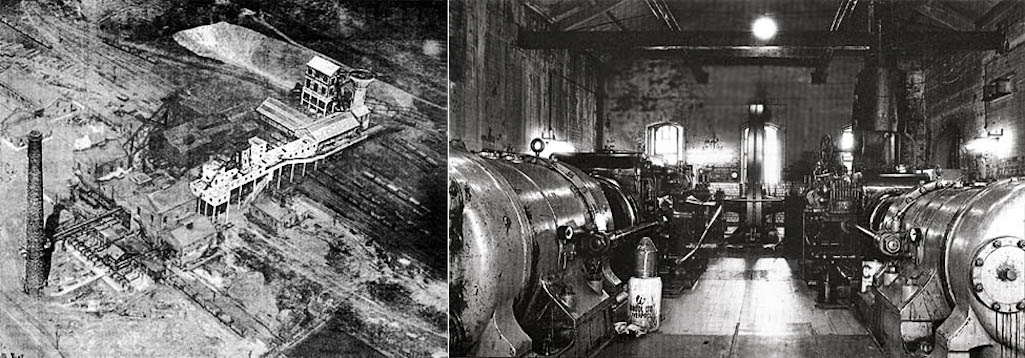

Sutton Manor Colliery dates back to May 1906 when no.1 shaft with a diameter of 18 feet was sunk by local coal proprietor Richard Evans. This was completed in December 1909 when the shaft was extended to a depth of 1,823 feet. The sinking of no. 2 shaft at Sutton Manor began in July 1906 with a shaft diameter initially measuring 22 feet. This was completed in 1912 and extended to a depth of 2,343 feet. The two shafts were inter-linked and it became one of the largest pits within the Lancashire coal field.

The accounts for the financial year of 1907-8 have survived and reveal that the colliery had a budget of £35,000 of which £1200 was spent on a boiler, £2,175 on winding engines, £1000 on railway and siding and £4000 was expended on wages. However, the creation of the new pit had more than a financial cost. On July 20th 1908, 34-year-old Fred Tiplady was employed erecting headgear until a chain broke, which caused him to fall 62 feet to the pit bottom, fatally injured him. He was far from being the last casualty at Sutton Manor.

In fact more than 60 people were killed working at Sutton Manor Colliery throughout its 85-year-history and over 270 were injured. Irish immigrant Patrick Joseph Fahey worked there during its early years and made quite an impression on his colleagues. He dug out injured workmates after what was probably a roof fall and then carried them on his back to the pit head. It's said they carved his name at the pit entrance in gratitude. Fahey, incidentally, became village bobby in Rainhill and his wife was the local midwife.

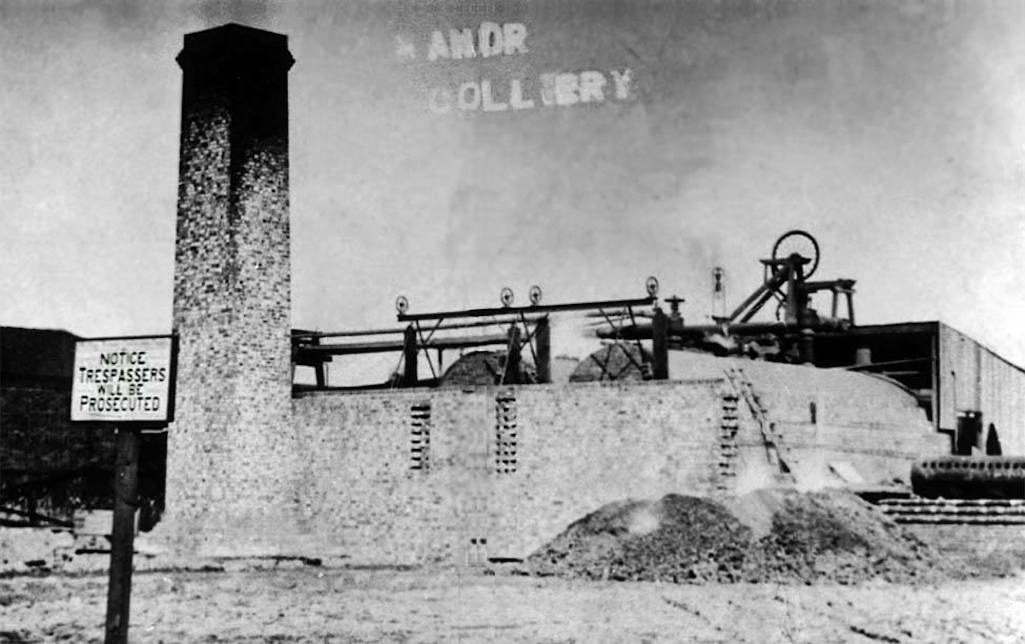

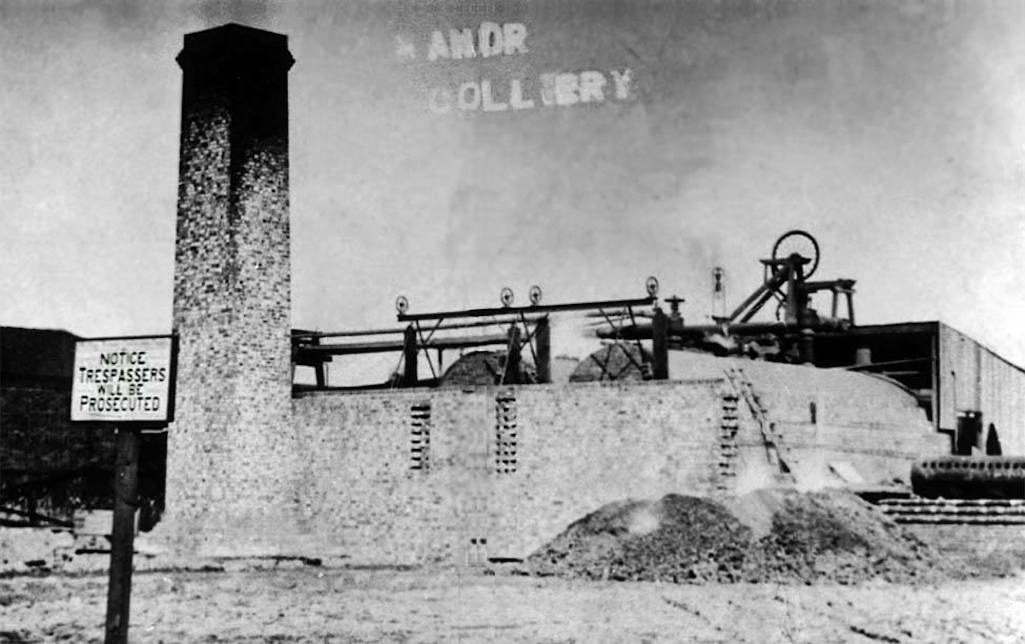

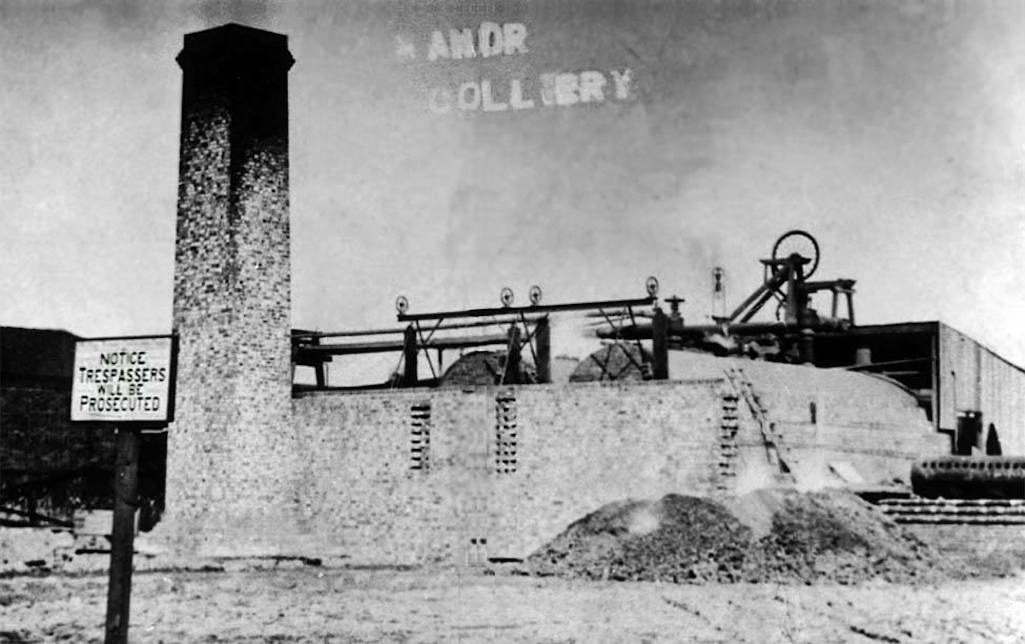

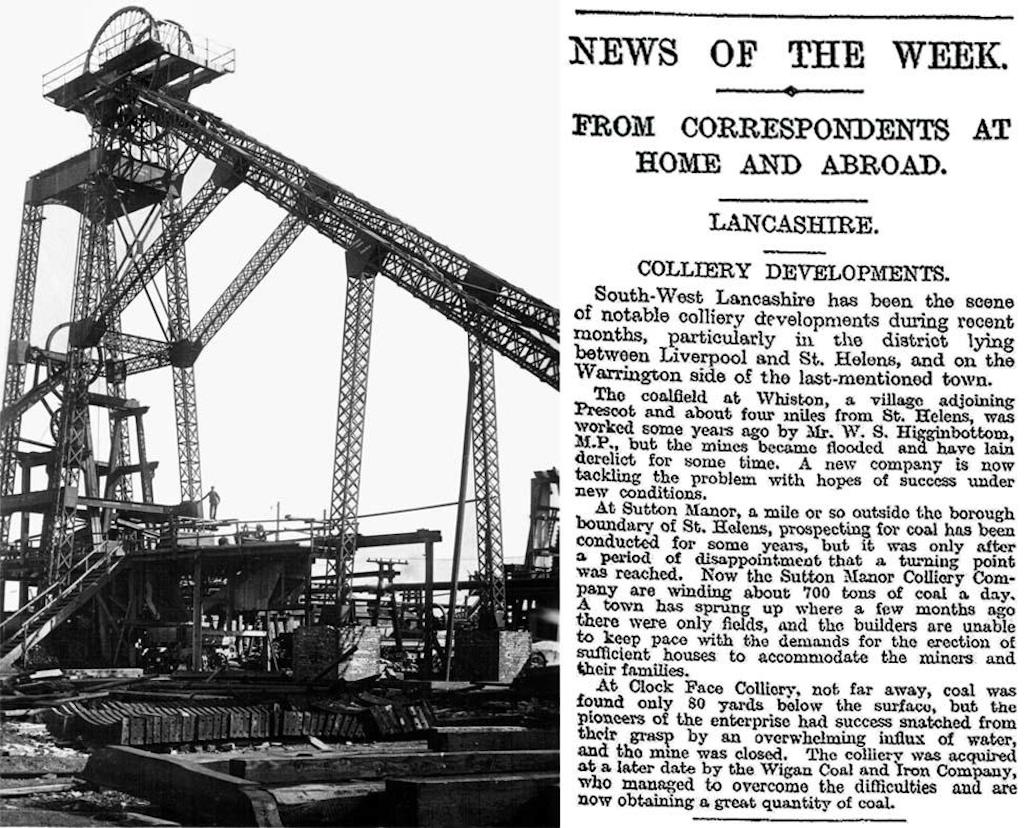

The first known photograph of Sutton Manor Colliery - undated but probably about 1915

The first known photograph of Sutton Manor Colliery - undated but about 1915

Sutton Manor Colliery about 1915

On November 27th 1913 Irishman Michael King met an unusual death down Sutton Manor. Shot firer William Brown had been asked to set off five ‘shots’ or charges in a tunnel where the 33-year-old King was employed. The third shot failed to go off and after several minutes, Brown disconnected the cable and removed the battery. The pair examined the cable and found a portion that had the outer covering split, leaving bare wires. Suddenly the shot went off, fatally injuring King and also injuring Brown. Such occurrences had happened before but were extremely rare and mine inspectors could not explain why, after the battery had been disconnected from the cable, shots should still explode. In the following year (on 18th March), John Lowton, a 15-years-old haulage hand, lost his life. He was crushed to death by runaway tubs of coal and was the youngest worker to die at the pit. Then on April 10th 1914 John Hughes was crushed to death by a roof fall.

However despite the accidents, it was an exciting time in the district. On February 2nd 1914, the Liverpool Evening Express - in an article entitled ‘Glassborough. A Prosperous Lancashire Town. How St. Helens is Growing’ - described the industrial advances being made in the town. The author wrote about the ‘wonderful development’ that was taking place at Sutton Manor in which extensive coal beds lay beneath its ‘smiling countryside’ and where growth had been ‘phenomenal’. It described how the venture had endured seven lean years until the financiers of the mine gave the management an ultimatum that unless coal could be found within a week, ‘the pit goes’.

The article went on to claim that it wasn’t until the seventh day of the deadline week that an Irishman named Duffy ‘bored his way right into a first-class seam of coal, and announced his find with a joyful Hurroo’. Sutton Manor had to overcome a number of difficulties in locating a seam of coal that could be economically extracted over the long term. Its coal seams were very deep and there were major faults in the strata. The latter created significant interruptions in the seams, causing directional changes that weren’t easy to track.

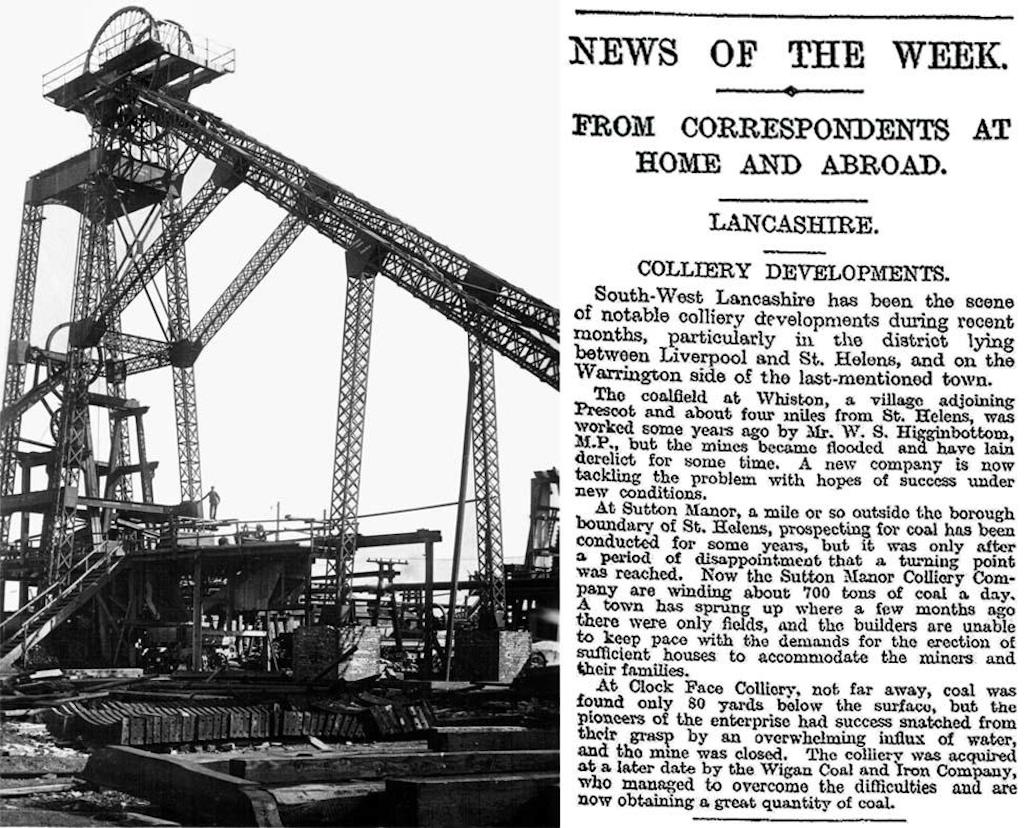

These and other factors led to expensive delays before coal could be wound up Sutton Manor's shafts but it was soon making up for lost time. The mine had only begun production in 1912 but by 1914 was already achieving an output of 700 tons of coal per day. The Times for their part reported how building firms were profiting as the newly-recruited Manor pitmen and their families needed housing:

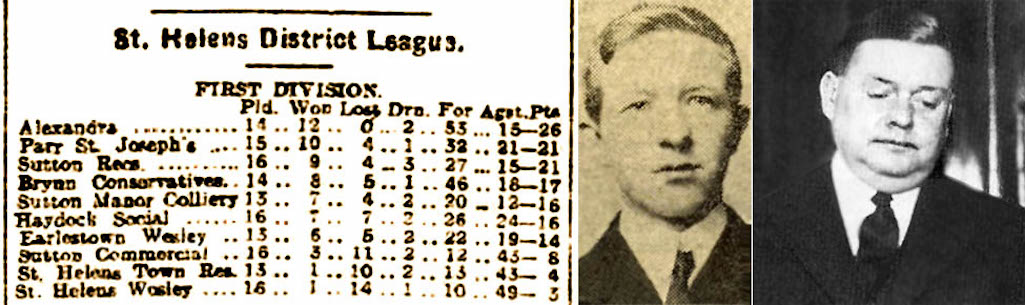

Left: 100 ft steel headgear constructed and erected by John Booth & Sons of Bolton c.1915; Right: Times article 4/2/1914

Left: 100 ft steel headgear constructed c.1915; Right: Times article 4/2/1914

100 ft steel headgear at Sutton Manor

On April 9th 1914, John Hughes was killed by a roof fall when using a coal cutting machine. This was not only a tragedy for the 41-years-old's family, it exacerbated Sutton Manor Colliery's recruitment problem. The company was experiencing a shortage of skilled men able to operate the coal cutting machinery and on July 28th manager Thomas Cook found himself in court. He admitted allowing some coal-cutters to work double shifts and so was prosecuted for breaching the Eight Hours Act of 1908. In fact Sutton Manor was the first colliery in the country to be charged with contravening the act.

Boys will be boys whether it's war-time or not. On March 23rd 1915 William Parr and Peter Ashton from Milton Street found themselves in front of St.Helens magistrates charged with releasing waggons at Sutton Manor Colliery. They'd allowed them to run onto the main line and had torn off labels, which had caused confusion as the waggons were addressed to different ships at the docks. For their bit of mischief, both boys were sentenced to six strokes of the birch. On April 6th 1915, 52-years-old Samuel Randles of Chester Lane was killed by a fall of roof.

In February 1916 an inquiry was held into the Sutton Manor Colliery Co.'s application to construct a new railway. This would connect the pit with the Liverpool & Manchester line opposite Lea Green Colliery and replace an inadequate temporary line, which was hampering its coal distribution. This had been constructed in 1904 / 5 and went from the colliery to a point just west of Walkers Lane and then via a branch to Roughdales Brickworks line. A private railway had also been built in 1905 to connect Sutton Manor with the St.Helens and Widnes line at Clock Face Colliery Sidings.

The 1916 L&M extension necessitated alterations to Jubits Lane, Walkers Lane and Lea Green Road, with some road diversions and overbridges required at an estimated cost of £1315. The colliery company agreed with St.Helens Council to contribute £800 towards the cost of the roadworks. The General Manager John Robinson revealed at the enquiry that they had lost between 300 to 400 men through the war but when it was over "there would be a great development and the district round the colliery would be a very busy one". He also predicted 70 years work at the colliery with the intention of generating an annual output post-war of 1 million tons of coal.

Left: Liverpool Evening Express 24/1/1914; Middle: Pte. Joseph Halsall; Right: Miners Agent Joe Tinker pictured in 1935

Liverpool Evening Express 24/1/1914; Pte. Joseph Halsall and Joe Tinker

Pte. Joseph Halsall & Joe Tinker in 1935

A boy called Matthew Brannelly from Walkers Lane appeared in St Helens Police Court on October 21st 1918 charged with having released the brakes of a coal wagon in a Sutton Manor Colliery siding. The wagon ran from Walkers Lane to Jubits Lane where it crashed into a gate causing considerable damage. The Bench was told that boys of the defendant's age (about 8) were in the habit of doing what Matthew had done but the company did not want the boy punishing. They considered him too young for punishment but they would ask the magistrates to seriously warn the parents of the child. Matthew's mother Emily had also been summoned to court and although she played no part in the incident was fined ten shillings. This, the Chairman of the Bench said, was to impress upon parents the need to prevent their children from trespassing on the line.

On the following day six men from Clock Face appeared in front of the St Helens County magistrates accused of trespassing on the sidings. In fact they'd been playing cards but the police had decided not to charge them with gambling. The men who were caught after a chase were Peter Light from Pendlebury Street, David Roberts from Jersey Street, Edward Tonge of Agnes Street, Thomas Taylor from Crawford Street and Peter Fillingham and John Lowe both of Agnes Street. It was stated that great trouble had been caused at the colliery by trespassers on the siding interfering with wagons and using them as a screen for gambling. The six men were each fined 20 shillings.

William Kelly (26) from Phythian Street was killed down Sutton Manor on January 7th 1919. A large stone weighing 10 cwt fell on top of him while he working in the Higher Florida mine. Two days later James Rimmer from Whiston suffered a dreadful death in the coal screening (a.k.a. scraping) section of the colliery. Rimmer was the foreman and somehow became fastened in the shafting, which whirled him round three times. He was then dropped into a coal scraper conveyor minus all of his clothes, which had been stripped off by the machinery. Rimmer had taken it upon himself to restart the machine after the engineer John Berry had stopped it after it became jammed. Berry from Jubits Lane told the inquest at the Clock Face Hotel that he had previously warned Rimmer about going under the shafting while it was in motion. Richard Gaskell of Lever Street in Clock Face also died at the colliery around this time.

In March 1919 Henry Bates, the Mayor of St Helens, told an inquiry into plans to build new homes on the Windlehurst estate that the council was also in negotiation with the Sutton Manor Colliery Company over housing. He said they were looking to provide the company with a site: “for accommodating people in that area at a very reasonable price”. The Inspector chairing the inquiry commented how that wouldn’t help people who were living in Parr. However Bates replied that it would, as the company currently had to run their own motor buses from Parr and the centre of St Helens to bring workers into Sutton Manor.

On June 13th 1919 Peter Colquitt from Clock Face Road and Albert Landers from Market Street appeared in court charged with absenting themselves from Sutton Manor Colliery. Essentially the two waggoners had had a long "snap" break. They’d left their place of work at 10:40am and not returned until an hour later, when only a 20-minute break was allowed. As a result four tons of coal output was lost at a cost of £4 and the company sought £2 damages from each of the men. In their defence Colquitt and Landers claimed that all the miners took similar breaks. However an award of £1 damages and 5 shillings costs was made against them both.

On December 10th 1919 the Sutton Manor Colliery Company applied in St Helens County Court for possession orders for six of their houses. No actual addresses were stated in the newspaper account of the proceedings. However all of the tenants were living in houses that the company had recently bought, although none were currently employed by them.

Over the last few years the colliery had built large numbers of new homes in Sutton Manor for the coal miners and their families. However more properties were needed quickly as they had 100 vacancies to fill but couldn’t recruit men through the remote location of their mine. The first case heard was that of John Winstanley who had a family of eleven. He was employed at Clock Face Colliery and had lived in his house for almost six years. Another tenant was Annie Greeley, whose husband had worked at Sutton Manor for 15 years but had been killed in the war. Mrs Greeley told the court that she was not in good health and her daughter was seriously ill.

To this the company’s estate agent remarked that she might be a "full-fledged invalid in court, but the way she carried on when I served the action to quit on her was abominable." The judge ruled in favour of five of the defendants but told them that they must try to find alternative accommodation. In the case of Mrs Greeley, the judge said the company should "do something" for the widow in the light of her circumstances and adjourned her case for three months.

On February 12th 1921 an inquest was held on Charles Roberts from Farnworth who was a brakesman employed at Sutton Manor. The 38-year-old was uncoupling coal wagons on a new siding and slipped over some heaps of waste and fell underneath a wagon. Charles suffered a fractured thigh and internal injuries and died in hospital soon afterwards.

Leisure facilities for the mineworkers greatly improved in 1922 with the opening of the Miners' Institute. This became the entertainment centre of the village and was a corrugated iron building situated in Jubits Lane, opposite Bell Lane. It had a bar room, a games room with billiard / snooker tables and a larger room that was used for dances and brass band practice. On December 31st 1934 the inaugural New Year’s Eve dance was held in the Institute. This annual event attracted around 300 people and proceeds were usually in aid of the colliery band and Sutton Manor Bowling Club.

On Sundays this room became the Sutton Manor C. of E. Mission and alcohol stopped being served. There was also living quarters that was occupied by the club stewards, who during the 1930s was the Greenall family. The outside sports facilities included a bowling green, two tennis courts and a cricket field, that was later used for football. In fact the Sutton Manor Colliery football team had been in existence almost since the start of the mine and during the 1913/14 season it was in Division 1 of the St Helens District League.

The explosions of firedamp - the flammable gas found in coal mines - was a common cause of accidents, as well as roof falls and haulage accidents, that were sometimes caused by youthful exuberance. On April 13th 1923, 18-year-old haulage hand William Gee from City Road died in St Helens Hospital after being involved in an accident with runaway coal tubs. The divisional inspector of mines said at Gee's inquest, held at St Helens Town Hall before veteran coroner Samuel Brighouse (1850-1940), that he'd probably been riding an empty box down a brow when the accident happened and so the coroner ruled misadventure. In June of that year it was announced that the Sutton Manor Colliery Company were building 150 more houses, taking advantage of the Ministry of Health's subsidy scheme.

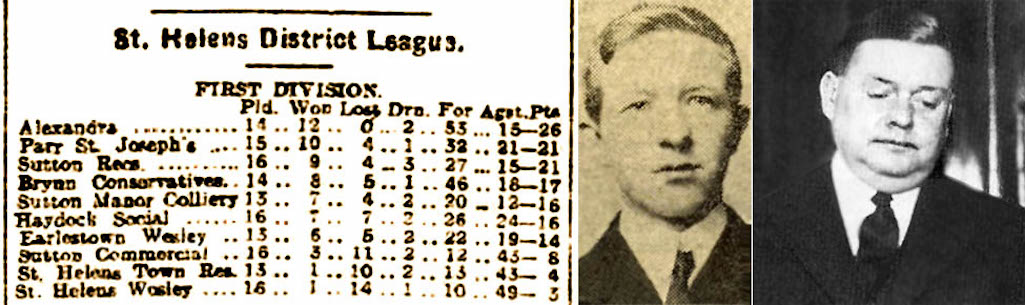

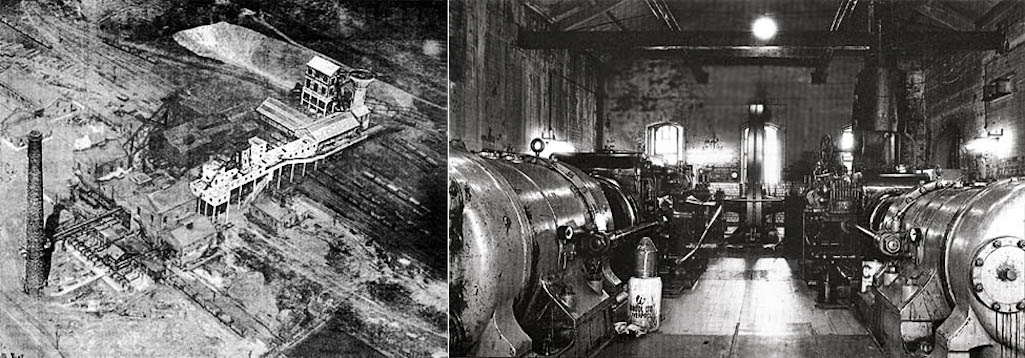

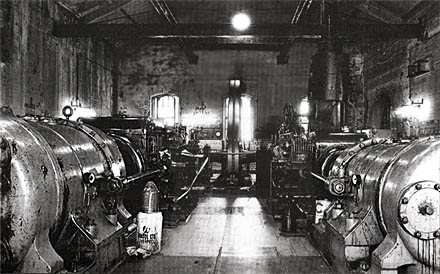

An aerial picture of the Sutton Manor pit c.1930 and compressors that powered underground machinery

Aerial picture c.1930 and compressors that powered underground machinery

Compressors that powered underground machinery at Sutton Manor Colliery

In order to keep the colliery in a safe condition, between 40 and 50 'safety men' were allowed to work down Sutton Manor during the lock out. They were responsible for making repairs and ensuring that the pumps kept on working. This was vital as otherwise there would be problems with flooding and ventilation, delaying a resumption of work. However in the middle of August, the residents of Sutton Manor were concerned to see much coal being raised to the surface. The management insisted that some coal had to be hauled, as a head of steam was required to carry out the maintenance. The union view was that there was sufficient coal already on the surface that they could burn.

A meeting of the union was held in Bolton on Monday August 16th and it was decided to withdraw the safety men. On the Tuesday morning, virtually all the village assembled to enthusiastically hear the news from the union leaders and picketers surrounded the colliery. Some of the safety men decided to ignore the order, leading to considerable tension. 'The situation is a dangerous one', commented the Manchester Guardian on the 18th, predicting trouble if the situation was not carefully handled.

On the Wednesday, a crowd of a thousand men assembled outside the colliery booing and shouting. The Manchester Guardian said the noise they made could have been heard over a mile away. A window was smashed in a worker’s house and a number of other workers were followed home by a crowd who loudly beat tins; a traditional sign of hostility. The colliery claimed that 25 non-union workers were still employed inside and decided to accommodate them at the colliery, to prevent further unpleasantness.

The Manchester Guardian predicted that life would be difficult for these men long after the dispute is ended, 'so fierce is the hatred felt for them'. The newspaper wrote how the cottage of one had been 'smeared almost to the eaves with whitewash' with 'terms of abuse scrawled over the window panes'. Over the next few days, more houses were daubed with whitewash but according to the colliery, the workers inside actually increased in number to 55.

Reporting to the House of Commons, Joe Tinker – the MP for Leigh and miners' agent – said that on August 22nd three thousand men had processed peacefully to Sutton Manor. Tinker, who lived in St.Helens, told MPs that police were rushed past them in wagonettes and charabancs. While their meeting was in progress, some of the 'blacklegs' showed themselves provocatively to the crowd and the pits' pulleys went round. Tinker claimed that it had been a direct incitement, which had been intended to start a riot, so the police could rush in and "give us the lesson they thought we should have."

Relations with the police became very poor. Gordon McDonald of the Lancashire & Cheshire Miners' Federation Executive argued that not all of the police in St. Helens were against the strikers but those on duty in Sutton Manor were becoming notorious. At a meeting McDonald said: "In a police force containing many thousands you will find dozens of brutes and cowards among them – in Sutton Manor, maybe, who will call Sutton women swine". Police were billeted in the colliery workshop and mining institute and in a lodging house in Jubits Lane and they paraded round the Manor in pairs challenging any small group.

For a short time the strikers and their families were allowed to gather coal from the colliery spoil heap but this became prohibited and the police looked out for offenders. The miners' institute was dubbed the 'scab club' as most of their patrons were the so-called 'blacklegs'. The locked out men were denied access and so built an alternative club in Walkers Lane out of two ex-army huts. In one incident in August 1926, alleged blacklegs David Eden and J. Chisnell were accosted on Jubits Lane while cycling to work by a dozen men armed with sticks and pick shafts.

In an article in the Hull Daily Mail of August 27th 1926, it was claimed that 50 men were employed on the Sutton Manor coal face with nearly 100 other colliers, enginemen and other staff working elsewhere at the pit. The report stated that they were under police protection with an 'army of wrathful men, backed by crowds of excited women' outside. At one point the hundreds of strikers thronging Jubits Lane were startled by two cartloads of coal that suddenly left the colliery. However they were pacified when told it was being donated to the local schools, so they could cook food for the children.

By October life was becoming intolerable for many Sutton Manor miners and there was a slow drift back to work. This culminated in two large bus loads of workers from Wigan and St Helens arriving in Jubits Lane on October 11th. The colliery manager said it was a larger return to work than they’d experienced during the whole of the previous week. This was a turning point in the dispute with the incentives being offered to the indebted miners being too great a temptation for many. Miners’ agent Joe Tinker said at a meeting on the 13th that they were offering "£1 bribes, a load of coal and back rent knocked off". The latter was important as many owed as much as £15. The colliery management was also visiting the men at home and telling them that unless they returned to work, their jobs would be given to others.

An announcement by the Board of Guardians that they would be reducing relief to miners' wives and children by 10% from the 21st was a further blow. About 300 men were now back at the colliery and long lines of loaded coal wagons were on the surface ready to be transported by rail. Still many more men held out and by November 24th the figure working was listed as only 541. That was just over a quarter of the total workforce, with 86 men having returned within the previous 24 hours as the colliery owners’ terms were being agreed by the unions.

A view of Sutton Manor Colliery pictured from Tennyson Street - photograph by Ian Lally

A view of Sutton Manor Colliery from Tennyson Street - photograph by Ian Lally

Colliery view from Tennyson Street

Sutton Manor mineworkers who got injured were entitled to compensation, although it was not on the same scale as today. In January 1927 James Cunningham was awarded 16s 3d per week in the County Court for an ankle injury he'd suffered nine months earlier. This was payable for as long as he couldn't work but was much less than his weekly wage had been.

On November 1st 1930 miner E. Keen took a day off work at Sutton Manor as he was a Communist candidate in the St.Helens council elections. He was promptly sacked by the colliery management but was able to claim 13 weeks victimisation pay from his union. After the three months was up, Keen applied for an additional two weeks pay, which was the custom. However the Sutton Manor Miners' Branch of the Lancashire and Cheshire Federation refused to support his application because he was a member of the National Minority Movement (NMM), which they said was "trying to smash the Federation". The aim of the NMM was to convert the revolutionary minority of the working class into a majority, in order to boost Communist influence. A furious Daily Worker attacked the Sutton Manor branch saying: 'By this action the secretary and the other local officials have shown that they support the coal bosses in victimising militant workers'.

Sutton Manor Colliery Institute Band around 1930 (contributed by Colin Atkinson)

The Sutton Manor Colliery Institute Band pictured around 1930

The Sutton Manor Colliery Institute Band pictured here around 1930

The above photograph shows the band around 1930. On the back row second from right is Ronnie Dorning; fifth from right is Fred Aitken and Assistant Bandmaster Percy Dutton is holding a trombone on the far left of the middle row. On the front row standing far right is the aforementioned Billy Kenyon and second from right is Ernie Howell. The man with a bow tie is probably a visitor from Clock Face called Pennington. On the front row, first left, is Jack Houghton (of Milton Street); second left is Fred Prole (Forest Road) and Jack Gaskell is the bandmaster in the centre. Fred Barton is second from right and John Gaskell, the bandmaster’s son, is pictured far right. Thanks to George Houghton for the identification and Colin Atkinson for the photo. Do please get in touch if you can identify any others.

Sutton Manor Colliery Band participated in many contests. In 1928 they were winners at Douglas, Isle of Man and at Wigan and then three years later they won the May Championship at Belle Vue. The band won the Boosey & Hawkes Challenge Cup In 1933, the Belle Vue Challenge Cup in 1936 and the Freckleton Challenge Cup in September 1938. For the latter competition the colliery band performed an original composition called ‘Wayside Scene’, which was written by John Ambrose Greenwood, the ‘famous conductor and composer’ - as the Prescot Reporter described him - who joined the band in the late 1930s. William Gaskill, who had greengrocers' shops in Clock Face and Sutton Manor, was also a conductor of the brass band.

Arthur Chesworth's Omega watch presented after 50 years as an engine winder (contributed by Andy McEwan)

Arthur Chesworth's Omega watch awarded for 50 years as an engine winder

Arthur Chesworth's Omega watch

During the 1930s, Sutton Manor Colliery's safety record improved, leading to less business for Samuel Brighouse. He was highly experienced at enquiring into the deaths of colliers during his 55-year-long tenure as coroner for South West Lancashire. As a consequence Brighouse developed considerable knowledge of mining practice and understood that accidents were inevitable in such a hazardous occupation. In 1935 when 37-year-old colliery haulage hand John Abbott Almond, who was employed at the Florida Mine of Sutton Manor's No.1 pit, was crushed to death by a six feet-long stone, Coroner Brighouse holding Almond's inquest praised the colliery management:

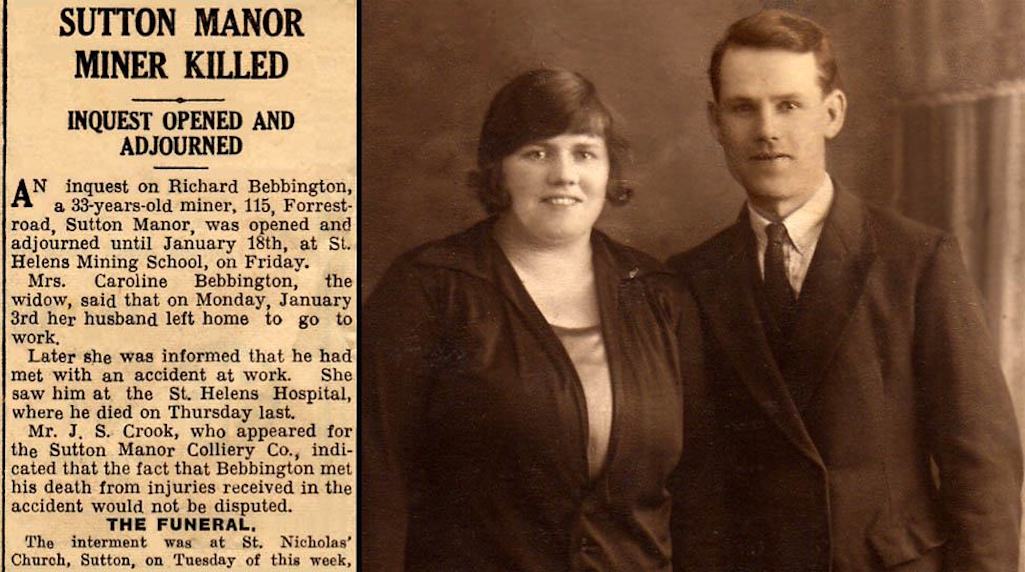

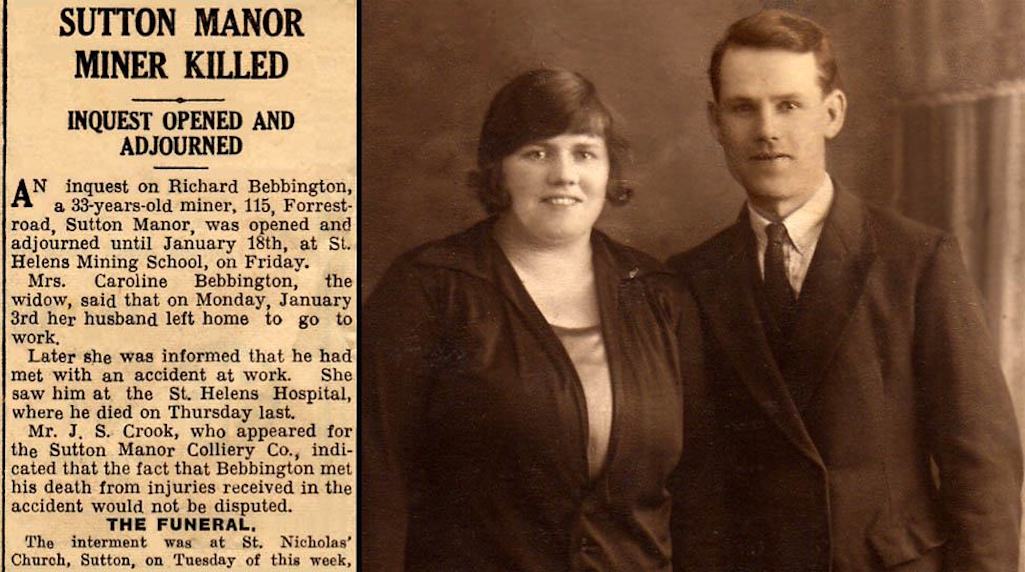

Richard Bebbington, miner at Sutton Manor Colliery, pictured with wife Caroline (contributed by Mel Moran)

Richard Bebbington, miner at Sutton Manor Colliery, pictured with wife Caroline

Richard Bebbington with wife Caroline

On August 26th John Platt suffered an accident at Sutton Manor and then lay in hospital for almost a year before succumbing to his injuries. The 39-year-old from 17 Milton Street had been having his ‘snap’ down no. 2 pit when bars and coal fell from the pit roof. One bar struck Platt across his back, fracturing his spine. Then on October 19th 1938, John Fazakerley at 70 years of age became the oldest Sutton Manor pitman to lose his life, after being crushed by runaway tubs. Both fireman Thomas Cook of Clock Face Road and Clifford Featherstone of Crawford Street had warned Fazakerley to take care while boxes of coal were being brought down. As a consequence of the accident, a new method of securing boxes was introduced.

In January 1939 the colliery claimed that 45 tons of coal was being stolen from them every week. The problem had become so bad that they had been forced to employ a man to patrol the colliery premises and sidings off Walker’s Lane to reduce pilfering from wagons. Also that month the decision was taken to close Holland Colliery at Upholland and transfer many of the 500 men (who lived at Skelmersdale, Rainford and Upholland) to Sutton Manor. This didn’t go down well with Sir Thomas Rosbotham, the Labour MP for Ormskirk, who complained to Captain Harry Crookshank, the Secretary of State for Mines, about the arrangement.

Rosbotham claimed in the House of Commons that several hundred men were going to be thrown out of work and he wanted the Secretary to stop such deals. Crookshank replied that most of the men would in time move to Sutton Manor and such transfers of supply sales quotas were essential to concentrate output in more efficient collieries. On April 15th 1941 the Sutton Manor (and Clock Face) miners who lived in the Skelmersdale district refused to go to work as a protest against increased bus fares.

On April 19th 1939 William Heaton was fatally injured at the colliery after a fall of dirt and coal from the pit roof. The 44-year-old from Orrell was using a compressed air pick about eight feet away from his brother Moses, when the collapse took place. The pair had been working together down Sutton Manor Colliery for 13 years and fireman James Cook of 82 Clock Face Road had previously inspected their place of work and decided it was safe. However at Heaton’s inquest he accepted that an extra ‘sprag’ (short supporting wooden prop) might have made the place safer. On August 5th 1939 John Platt of Milton Street died in St.Helens Hospital, a year after fracturing his spine down the colliery. Three bars in the pit roof had suddenly collapsed on the 39-year-old, pinning him to the ground.

Then on New Year’s Day 1940, 50-year-old William Roberts, of 49 Waterdale Crescent, succumbed to silicosis and tuberculosis after working down Sutton Manor Colliery over 15 years. Silicosis is the dreadful lung disease caused by the inhalation of coal dust, which also caused the death in December 29th 1940 of 50-year-old coal hewer John Robson of 92 Milton Street. 17-year-old Ernest Hamer, a haulage hand of 209 Mill Lane, was killed at the colliery in September 1941 and then on December 15th, 31-year-old Joseph Traverse of Derbyshire Road died as a result of a roof fall. On March 2nd 1942 a girder and part of the roof collapsed on James Morris in the Potato Delph area of the Florida mine. The 42-year-old fireman from Gartons Lane was quickly brought up to the pit-head but was found to be dead.

Mary Ludden on the coal belt at Sutton Manor Colliery's screens (contributed by daughter Jane Mines)

Mary Ludden a ‘pit brow lass’ on the coal belt at Sutton Manor's screens

Mary Ludden on the screens’ coal belt

Former Sutton Manor screens ladies

The showers in the baths at Sutton Manor Colliery during demolition in 1992 (contributed by Mel Moran)

The showers in the baths at Sutton Manor Colliery during demolition in 1992

Baths at Sutton Manor Colliery in 1992

In 1943 two former Sutton Manor Colliery miners, both from Forest Road, died from silicosis. 69-year-old former colliery fireman Henry Hancock died on January 31st and 45-year-old Wilfred Houghton passed away on December 7th. On September 2nd of 1943 coal cutter George Smart of Lever Street in Clock Face was killed when a 3-foot stone fell from the pit roof onto his head and another dropped onto his body. At his inquest it was revealed that the 40-year-old was wearing a cloth hat instead of his helmet. Coroner Cornelius Bolton said: “If men would wear their helmets many lives would be saved. The helmets may be a nuisance, but they save men from death”.

During the 19th century mineworkers were sometimes taken to court for failing to turn up for work. This rarely happened in later years, apart from wartime, when coal had a greater national importance. So on December 30th 1943 haulage hand Henry Foster found himself in court facing three charges of being absent from Sutton Manor Colliery without reasonable excuse. The 18-year-old from Clayton Street in Skelmersdale, was fined a total of £9 (about £300 in today’s money).

On July 8th 1944 57-year-old hewer Charles Hawksworth of 120 Peasley Cross Lane died in St.Helens Hospital after being injured two days earlier at Sutton Manor by a roof fall. From that year Sutton Manor deputies or others with first aid training were authorised to give morphine (or morphia) injections to injured men. By the 1970s entonox and pethidine had replaced morphine as the analgesic of choice.

During the war and for several years afterwards, a number of so-called 'Bevin boys' were conscripted to work at Sutton Manor instead of going to fight. Many lived at the 'Bevin huts' at the top of Grimshaw Street in Sutton Leach. Most weren’t trade union members, which strained relations with the union men. On October 21st 1946 the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) branch at Sutton Manor Colliery gave notice that from November 4th, union men would not work with or ride in the pit cage with non-union staff. In the event it became a fully-fledged strike by 1200 miners.

Many of the Bevin boys did not feel that they should have to join a union, as they were only in temporary employment. The colliery company offered to segregate the 140 non-union staff from union men but this was rejected by the NUM. The dispute was quickly settled, however, after Edwin Hall, Lancashire secretary of the union, held a meeting with the Bevin boys on the evening of the 5th. He pointed out how the union had fought to obtain advantages that the pitmen now enjoyed and urged them to consider their duty to the men who would follow them. Impressed by Hall’s, words almost every Bevin boy agreed to join the union, the strike was called off and the night shift went to work.

The extensive use of the baths at Sutton Manor and other pits was causing problems for bus conductors as miners were too clean! Under a heading 'You can't tell a miner these days', the St.Helens Newspaper of October 14th 1949 reported how St Helens Corporation had successfully applied to the Liverpool Traffic Commissioners' Court for permission to cease colliers' day work return bus tickets after 9am.

This was because bus conductors were unable to distinguish between miners and other workers as they were taking 'full advantage' of the pithead baths. This short story was placed on the front page of the newspaper, adjacent to a lengthy account of the death of Peter Fitzhenry at Sutton Manor. The coroner at his inquest, Cornelius Bolton, described it as "...the old, old story all over again of bolting the door when the horse has gone."

The 67-years-old haulage hand from Milton Street died in St.Helens Hospital just over two weeks after being injured in No. 2 pit. He was struck down on September 24th 1949 by a runaway empty tub that young inexperienced Thomas Maher of Sutton Road had failed to secure. Since the accident, a warrick (or warwick) safety device had been installed by the management to prevent unbalanced loads from running away at that location. This was too late for elderly Irishman Peter Fitzhenry, who'd worked at Sutton Manor for many years despite only having one arm. The man who Charles Tyrer, the President of the Lancashire and Cheshire Miners Federation, described as a 'grand type of worker' lost an arm in 1917 as a result of injuries sustained in the Battle of Arras, after volunteering to fight for the British in WW1.

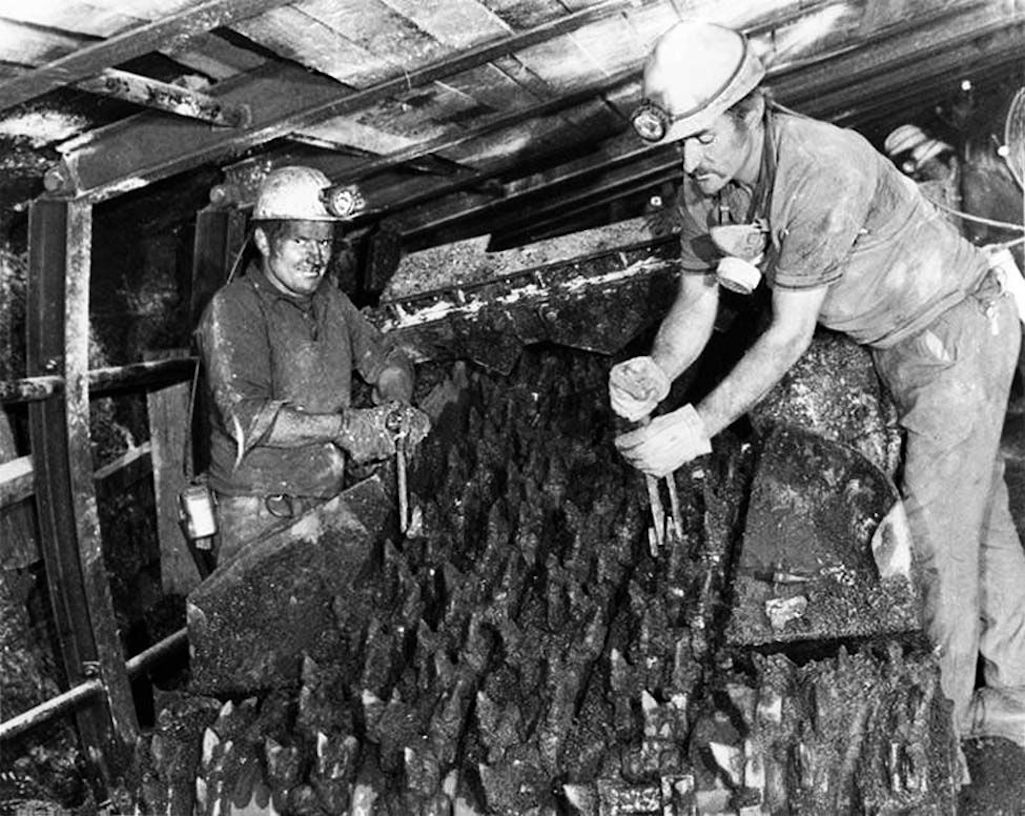

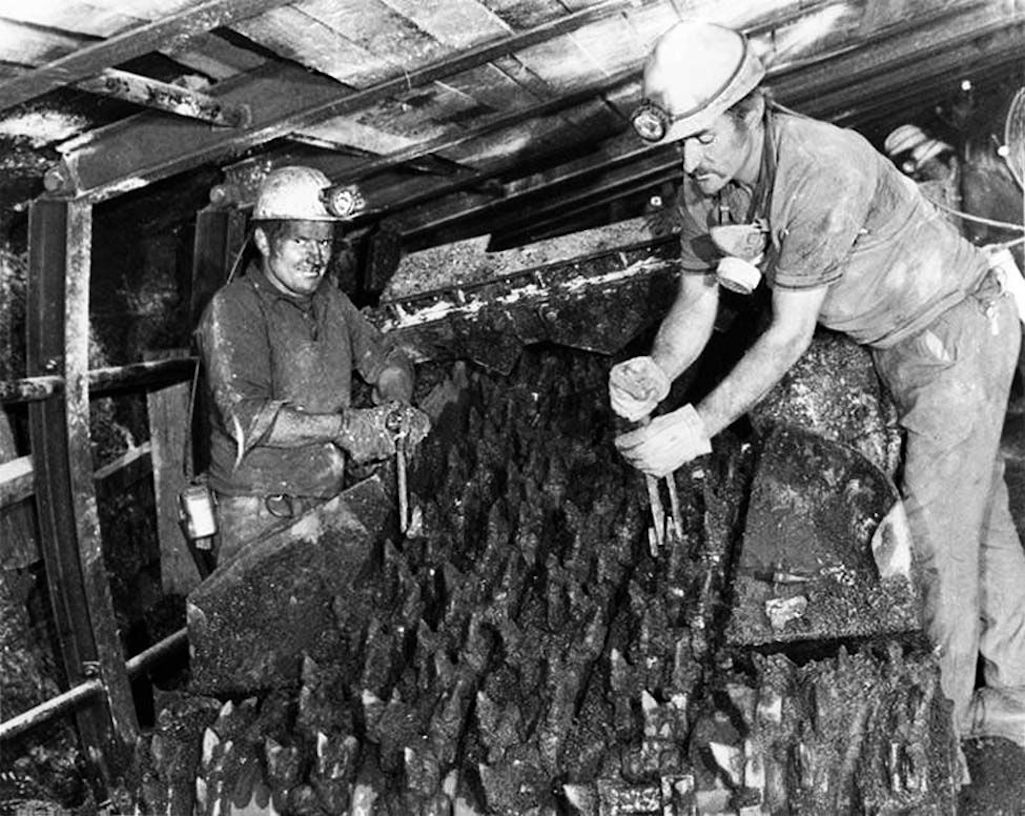

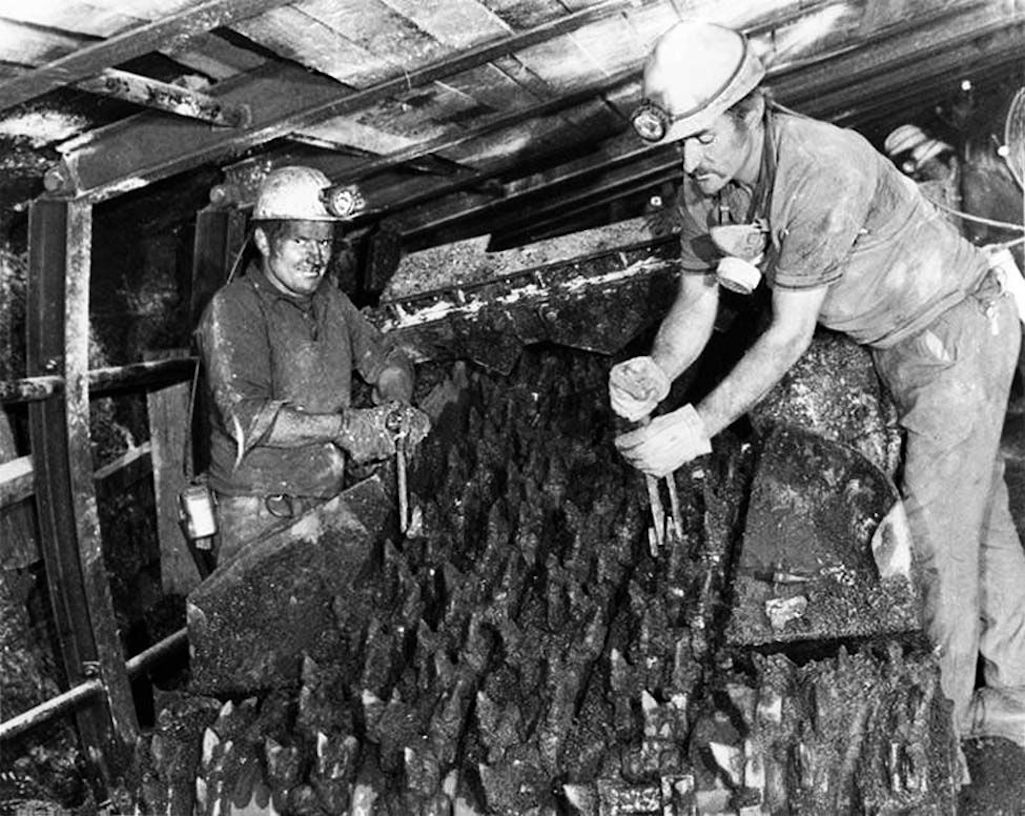

Changing the cutter picks on the road heading machine which cut the coal then transported it back down the shaft

Changing the cutter picks on the road heading machine which cut the coal

Changing the cutter picks on the road heading machine at Sutton Manor

A deal was then struck between the employers and the Lancashire secretary of the NUM, Edwin Hall, and its president Charles Tyrer, in which Horrocks would be released from prison and the miners would return to work. However the Sutton Manor lads weren't consulted and although Horrocks was duly released, they initially opted to stay out. Then the NCB and NUM issued a joint statement saying that negotiations were being opened to settle the question of the outstanding damages, with the Coal Board promising not to press for immediate payment. So a meeting of the Sutton Manor men was held and a vote was taken to resume work on September 11th. But five days later, twelve more Manor miners, who hadn't paid their breach of contract fines, were despatched to Walton.

The shocked Sutton Manor branch of the NUM met and voted to pay the imprisoned men's fines. They were told that £117 8s. 6d. was needed, which was a substantial sum in those days, and there wasn't enough in the kitty. So branch treasurer Joe Tyson ended up borrowing from family and a neighbour to make up the shortfall and get his colleagues released. The disgusted NUM members in Sutton Manor also passed a resolution calling on Charles Tyrer, the Lancashire area president of the union, to quit his post.

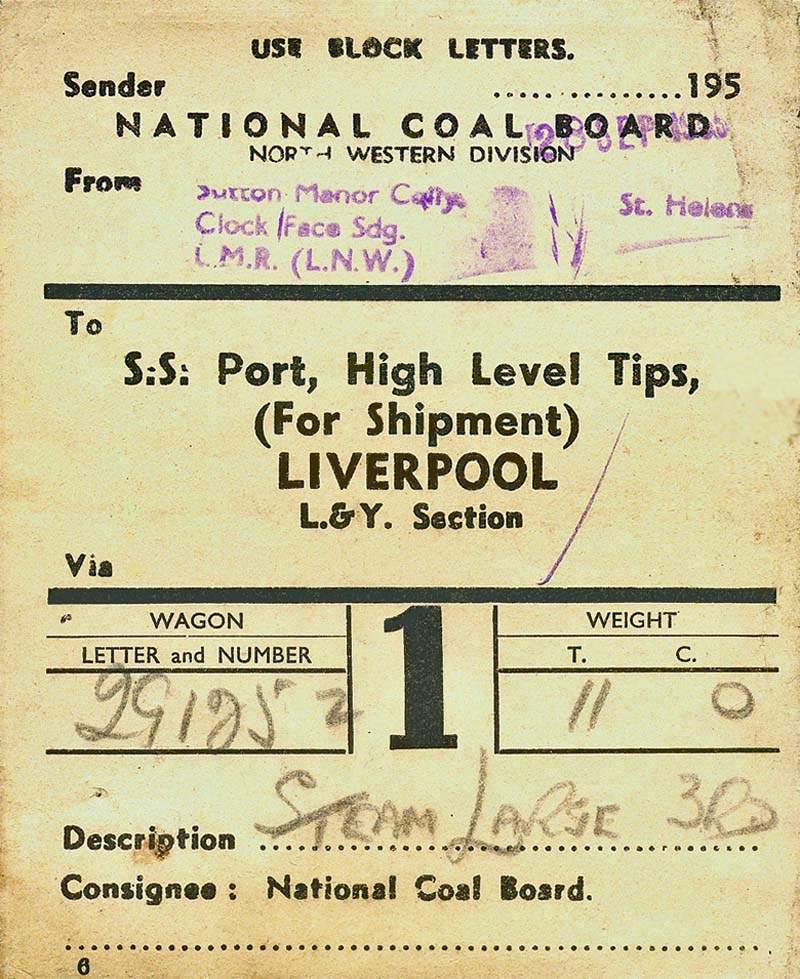

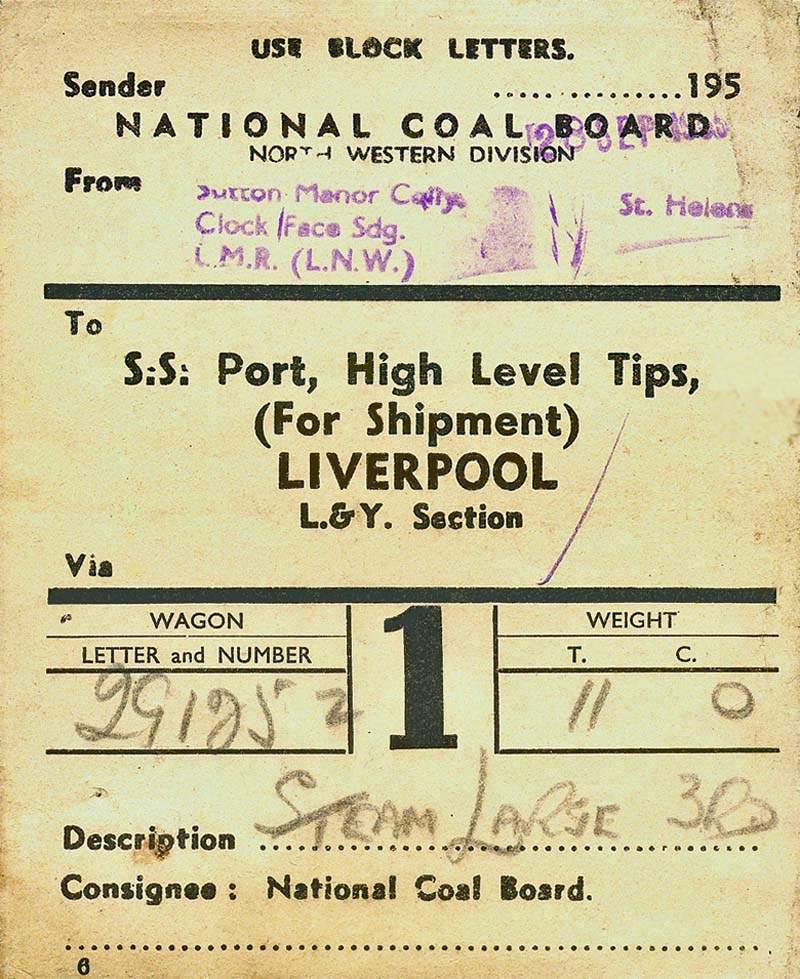

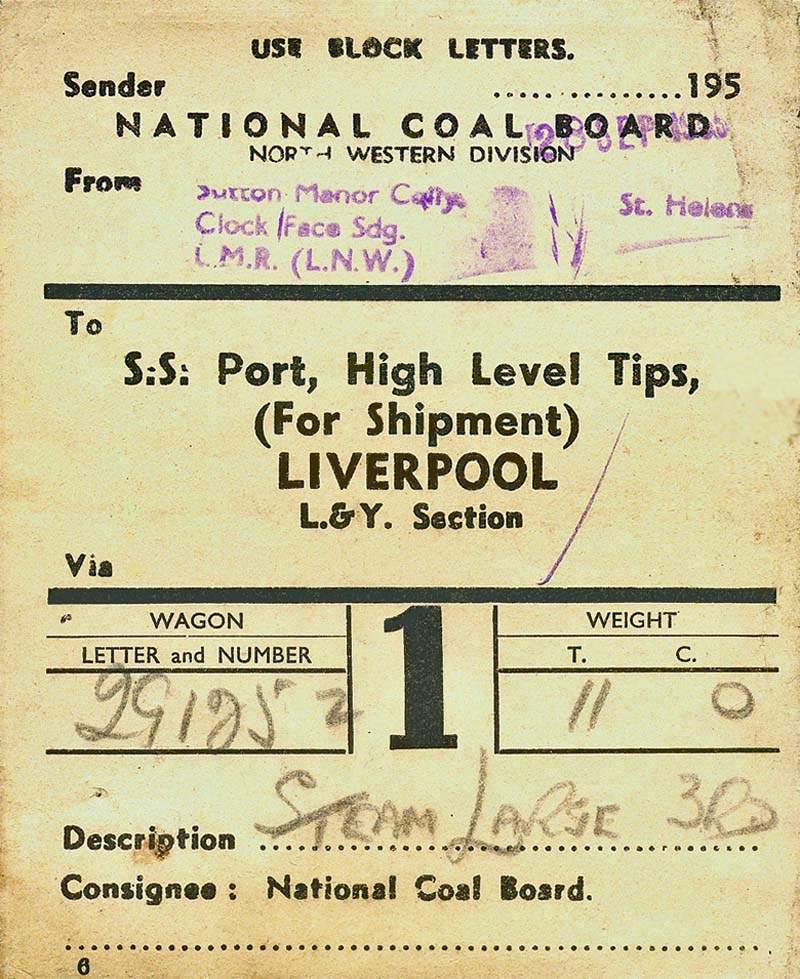

NCB Wagon Label - Sutton Manor Colliery to Liverpool Docks from September 28th 1955

NCB Wagon Label - Sutton Manor Colliery to Liverpool Docks from 1955

NCB Wagon Label from Sutton Manor Colliery to Liverpool Docks 1955

In September 1953 Polish miner Jan Szumczyk was working on his knees in the colliery when a large stone fell from the roof on to his back paralysing him. The 29-year-old’s employers were the Associated Tunnelling Co. of London, who were driving a tunnel down Sutton Manor. However they were absolved of all blame for the accident as the roof had been insufficiently propped, which was the responsibility of the colliery. So it was the National Coal Board who on November 17th 1955 were ordered at Liverpool Assizes to pay the sum of £13,553 to Szumczyk, who would be in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. The former paratrooper in the Polish Brigade had taken part in the raid on Arnhem during WW2, escaping by swimming the Rhine.

Post-war and under the management of the National Coal Board mines would close down for two weeks during the summer to allow for holidays. Domestic coal demand was greatly reduced between July and August but industry still needed coal and the NCB had to ensure that the 74 mines in Lancashire were not all closing down at the same time. So in February of each year Edwin Hall, the National Union of Mineworkers area general secretary, would announce the agreed closure dates for each pit. In 1954 Hall stated that Sutton Manor mineworkers would have the last week of July and first week of August for their holidays. The dates were largely decided by town, so most St.Helens’ collieries also closed down during those weeks but almost all Wigan pits had the first week in July and the first week in September. It was never a complete closure as ongoing safety work and maintenance would continue.

On August 21st 1954 a fire on the belt underground led to John Kinsella of Forest Road, James Smith of Park Road and William Sholkker from Huyton being taken to hospital suffering from gas fumes. On December 21st of that year, the London Gazette reported that two Sutton Manor pitmen’s actions during the incident had led to them being honoured for bravery. Deputy George Corrigan and coal-cutterman Ernest Gee were awarded the Queen's Commendation for brave conduct. Corrigan later moved to Lea Green Colliery but modesty stopped him from talking about his award. Gee also received the Daily Herald Award for Industrial Heroism, along with a tribute from Lancashire miners.

After making his way to the fresh air base, the 44-year-old from Billinge had returned to the danger area three times to rescue Kinsella, Smith and Sholkker, who had each been overcome by gas. "There is not the slightest doubt that these men owe their lives to his heroism", said area secretary Edwin Hall. Sadly eight years later (on July 5th 1962), Ernest lost his own life at Sutton Manor Colliery when he became trapped in a conveyor belt 500 feet below ground.

On May 22nd 1955 Sutton Manor played its part in a special celebration at Blackpool when 600 veteran mineworkers from Lancashire paraded through the town. Every man had retired during the previous year after serving at least 50 years in the industry. Area NUM secretary Edwin Hall explained to the press that the outing was organised by the Coal Industrial Social Welfare Organisation – a joint NCB and NUM body – to thank the men for their service. The Sutton Manor band was one of several that provided music in the procession with some of the marchers also from the colliery. The ex-miners arrived by special train and received a lunch at a civic reception hosted by the Mayor of Blackpool and 10 shillings each for their teas.

On August 10th 1955 a protective ‘plug’ of concrete 6 feet thick saved five men at Sutton Manor, after a pit cage hurtled down the 600-yard shaft. At the same time the other pit cage – which was empty – flew to the top of the winding gear but a safety device prevented it from damaging the shaft’s headgear. The men were deepening no. 1 shaft, when the cage carrying materials smashed onto the protecting ‘ceiling’ above them. The uninjured but shaken workers, who were employed by the Midland Tunnelling Company, managed to climb through an airway and were brought to the surface up the other shaft. Coal production was suspended and it took several days to repair the damage and resume normal operations.

During these post-war years, Sutton Manor Colliery was in its heyday with output rising and innovative methods employed to produce coal. In 1956 the colliery became the first working mine in St Helens to divert the deadly gas methane in order to fire its boilers. This was expected to make considerable savings in the colliery’s own use of coal and boost coal output by permitting shot-firing on certain faces where it had previously been banned for reasons of safety. Three years later Sutton Manor recorded its highest number of men on its books, 1682 workers in total. The long-term future of the colliery looked bright. However it wasn't to last.