An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 87 (of 95 parts) - Sutton Manor Colliery Part 2 (1960 - 1991)

Lea Green Colliery | Bold Colliery Part 1 | Clock Face Colliery

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me

Sutton Mineworking | Lea Green Colliery

Clock Face Colliery | Bold Colliery Part 1

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

The club's committee limited the number of spectators, rearranged the furniture and even bought shorter snooker cues. But it was all to no avail and so three walls of the newly-built club were knocked down and it was rebuilt at a cost of more than £2000. The story of 'Miners Snookered!' even made it into the Times! In the Guardian's account, steward Edward Gallagher said he thought that when the club was at the design stage, they simply measured two snooker tables, forgetting that people have to stand behind them to play.

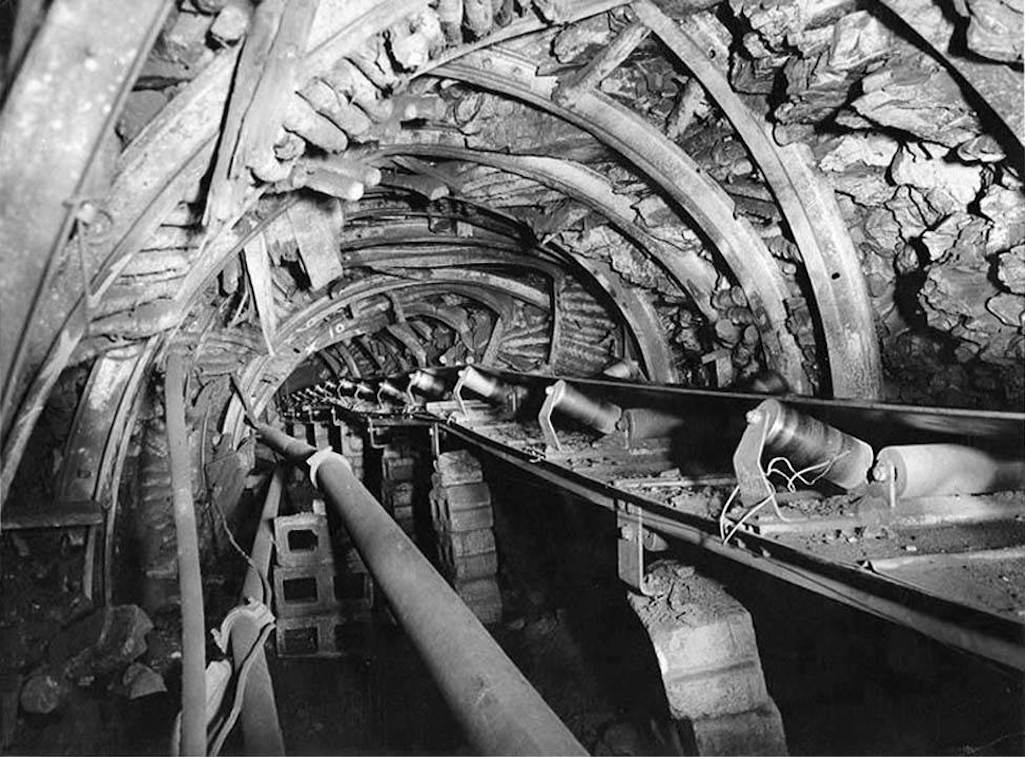

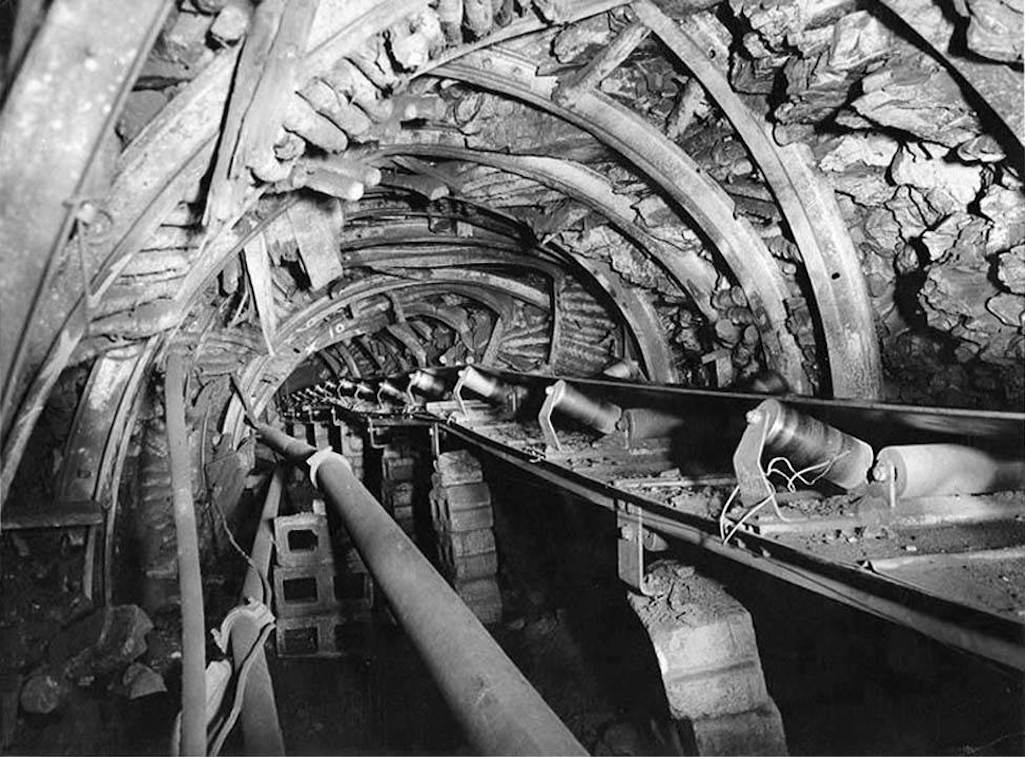

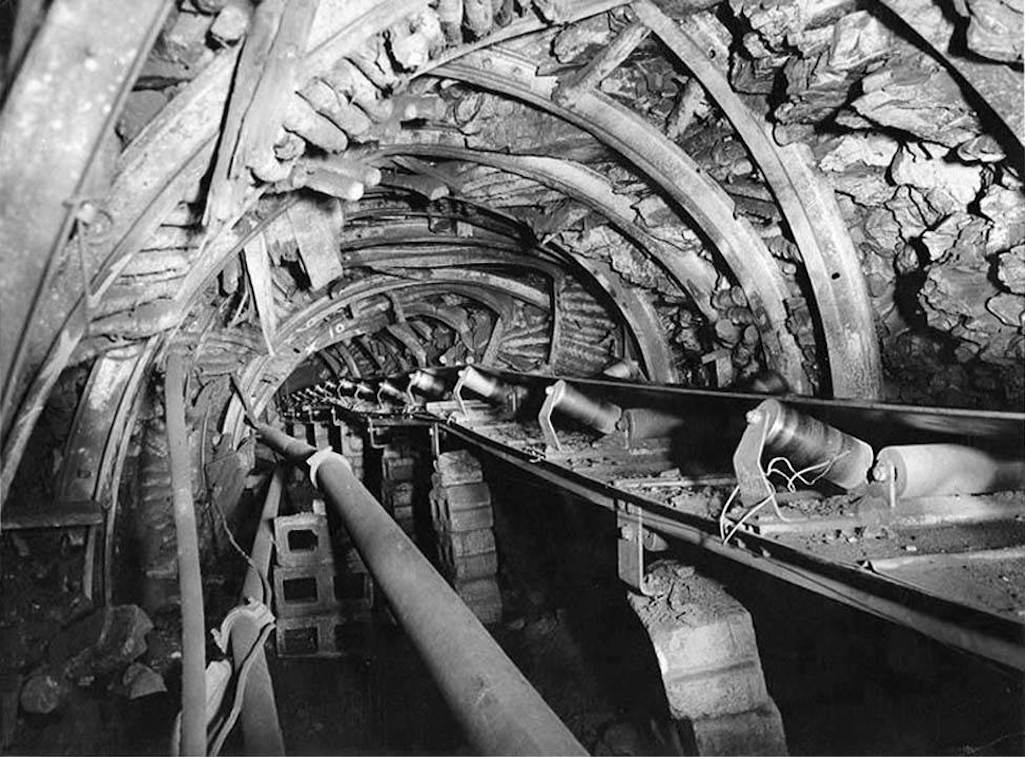

An example of a mining hazard at Sutton Manor Colliery caused by geological pressure

Example of a mining hazard at Sutton Manor caused by geological pressure

Example of a mining hazard at Sutton Manor caused by geological pressure

This 1964 view from St.Nicholas church tower has Sutton Manor Colliery behind Mill Lane - contributed by Jim Lamb

This 1964 view from St.Nicholas shows Sutton Manor Colliery behind Mill Lane

This 1964 view shows Sutton Manor Colliery at the rear of Mill Lane

Sutton Manor Colliery tallies were issued to each miner as a safety check so it was known how many men were underground

Sutton Manor Colliery tallies were issued to each miner as a safety check

Three Sutton Manor Colliery tallies

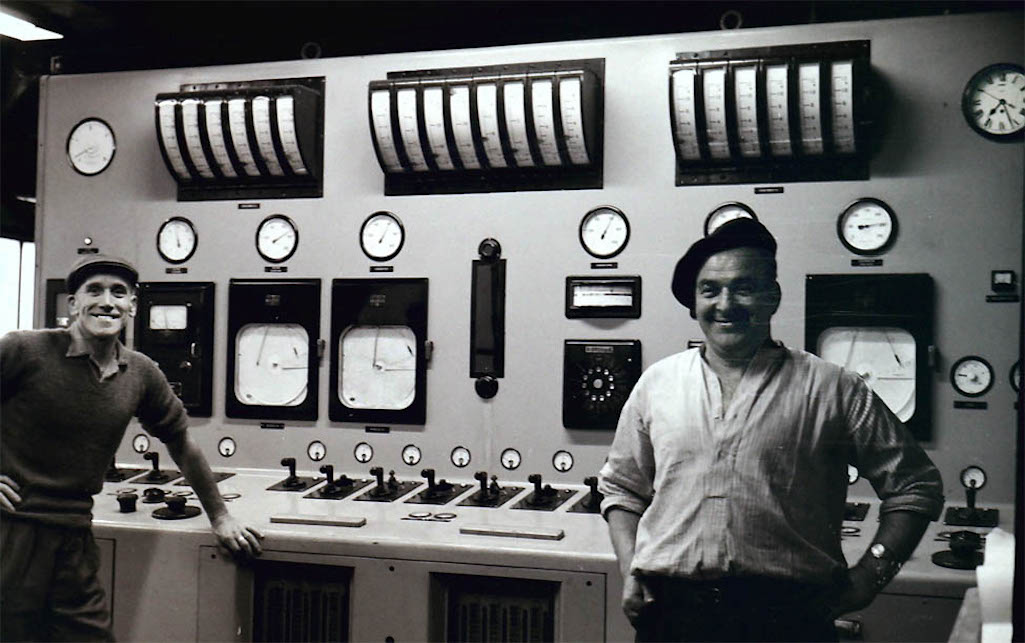

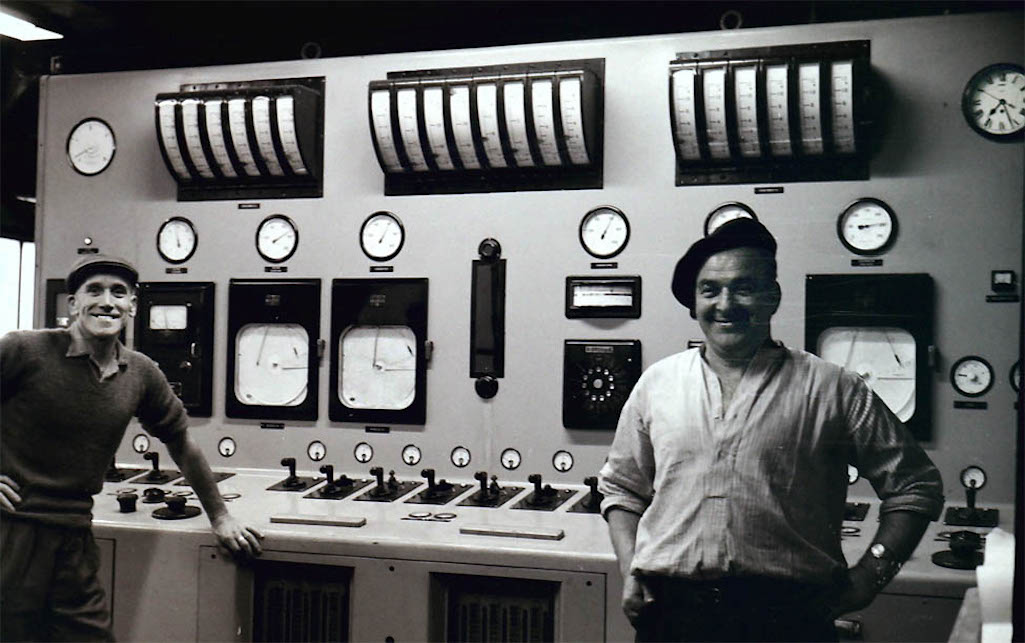

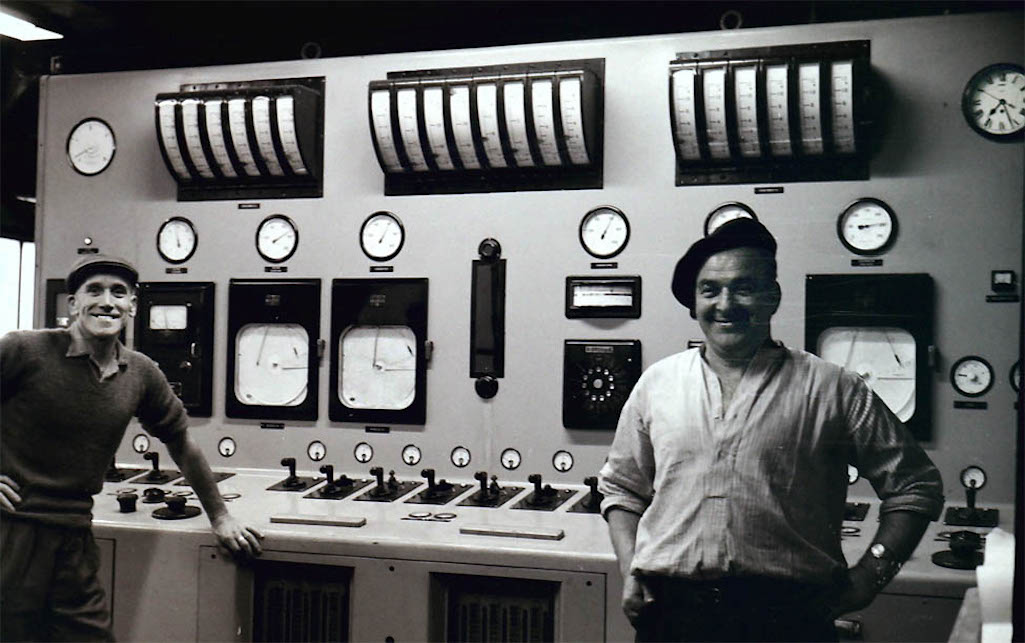

Sutton Manor Colliery boiler control room taken during the early 1960s - Contributed by John Gill

Sutton Manor Colliery boiler control room taken during the early 1960s

The colliery’s boiler control room

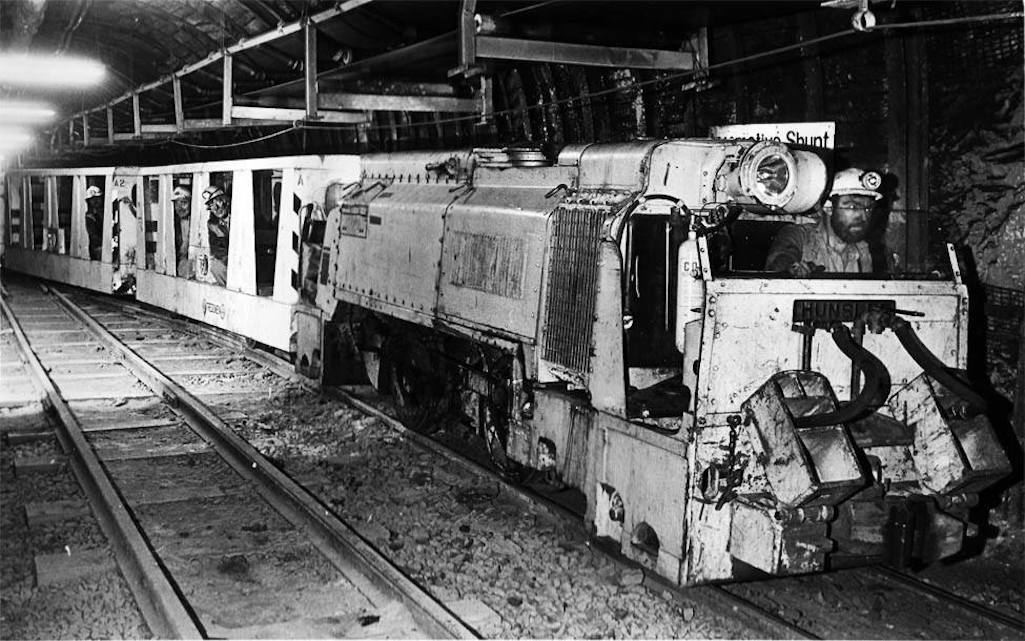

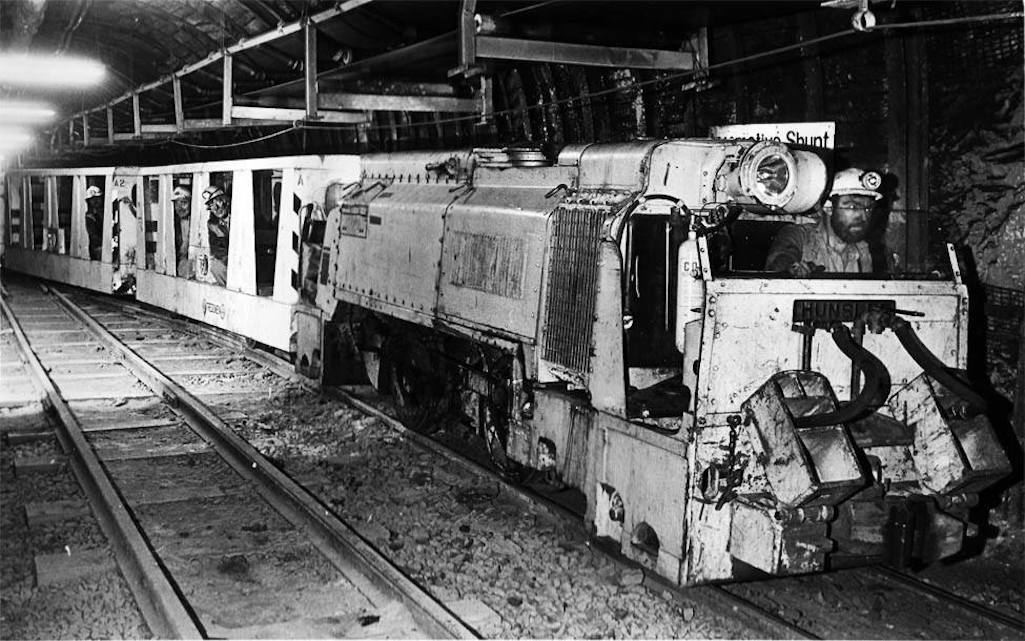

Albert the underground loco at Sutton Manor Colliery (contributed by Les Dunning - pic by Ian Lally)

Albert the underground loco at Sutton Manor Colliery - picture by Ian Lally

Albert the underground locomotive

In March 1968 the NCB announced plans to cease coal production in No. 1 pit, in order to concentrate resources on the more economic seams within pit No. 2. The local NUM branch organised a mass meeting of mineworkers to discuss the proposals and the decision was taken to oppose them. This was despite a warning by area secretary Joe Gormley that a refusal to accept the plans could jeopardise the future of No. 2 pit. Sutton Manor’s secretary Joe Connelly disagreed, telling the St.Helens Reporter that:

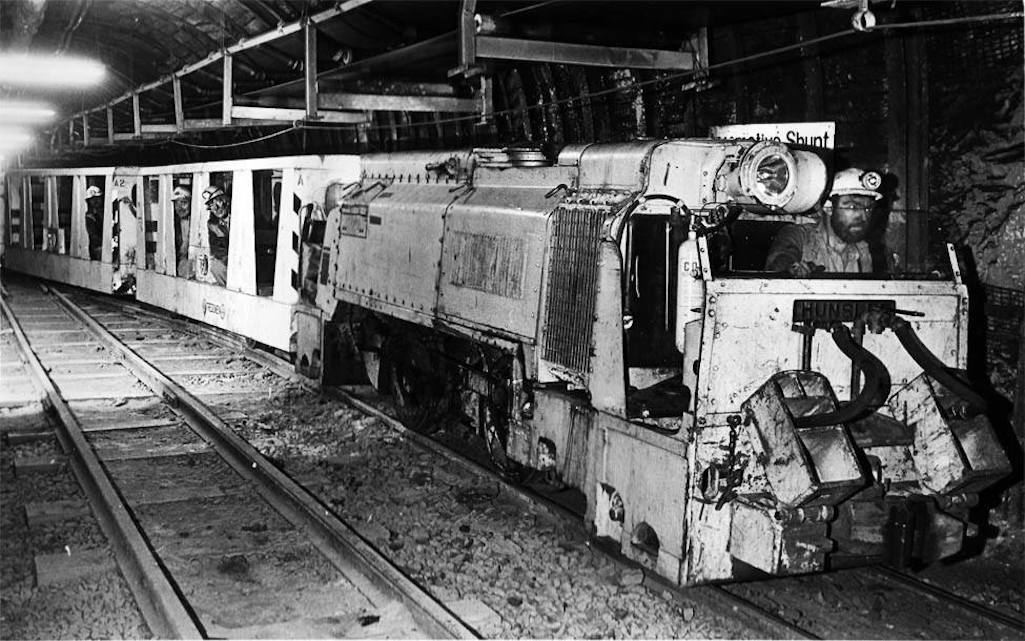

Shaft No. 1 was still used by the colliery for essential ventilation as the downcast shaft and for winding operations for men and materials. No. 2 pit was the upcast shaft for winding coal tubs and where air exited the mine following its transit around the workings. The outside of No. 2 shaft was closed and sealed by concrete walls with the colliery’s main fan connected to this shaft via a fan drift. The fan drew air around the mine, with fresh air in effect being sucked down No. 1 shaft. Men and coal tubs entered and exited the upcast shaft through an airlock system.

Unloading involves pushing the full tubs out of the cage to the other side, where they travel to the tipplers which empties them and they then come back round the circuit to the loading level. On the left of the photo you can see the safety gate guarding the shaft where the other cage is at its bottom, carrying out the same operations of loading and unloading. Materials such as steel arches, timber etc. are sent down the shaft in the same tubs, or longer trams, which are loaded in the colliery stockyard. Small windows of time are given for the winding of men up and down the shaft, while the tubs are out of the cages. (Description by Harry Hickson)

On May 17th 1969 John Kenyon - a 42-year-old fitter from Elizabeth Road in Haydock - lost his life while dismantling a coalface cutting machine. It somehow moved or slipped, which caused a part of the machine to detach and strike Kenyon, fatally injuring him. In November 1969 the NCB launched a recruitment drive to fill 500 vacancies at nine Lancashire mines, including 80 at Sutton Manor. A four-month long advertising campaign sought to recruit former miners, youths for apprenticeships and men without prior mining experience.

In the St Helens Reporter of December 5th 1969 it was stated that Sutton Manor miners had set a new productivity record during the previous week when their overall output per man-shift reached 51 cwt. That was 7 cwt above the national average, with most of the colliery's output coming from their W3 coal face. In the following week it was reported that they had smashed their productivity record once again with their overall output per man-shift reaching 53 cwt. Their Wigan Four Feet No. 3 face also broke a record with an advance of 72 ft. With a new face set open shortly, productivity was expected to increase even further.

The lead story in the St Helens Reporter of December 19th 1969 described how Sutton Manor mineworkers were upset about the quality of their concessionary fuel. Those living locally in miners' houses were now in a smokeless zone and they were far from happy with the coke that they were being supplied with. Not only was it generating less heat than coal but it was also said to often explode, spitting embers across living rooms, burning carpets and injuring people.

"It's just like being under fire", said Paul Bannister of Forest Road. The 51-year-old worker in the winding engine house told the paper that his wife Dorothy had a scar above her lips where a piece of fuel had shot out of their fire and stuck to her face. Engineman Tom Rigby of Milton Street complained that he not only had great difficulty in lighting the coke but when he did get the fire going it was very dangerous. "Last week a piece flew out of the fire and stuck on my spectacles", he told the Reporter. "If I hadn’t been wearing them my eye would have been injured."

The St Helens Reporter on January 9th 1969 described how mid-day meetings between management and coalface teams were boosting productivity. Each day the meetings highlighted any difficulties that the men on the morning shift were experiencing, which assisted the planning of the afternoon and night shifts. Manager Ken Moses brought the idea to Sutton Manor after using it successfully while working in Wigan. The article said productivity had shot up at the colliery since these meetings had been introduced.

In July 1972 Austin Marsh spent 12 days on an all expenses paid trip to West Germany's Ruhr coalfield for a first-hand look at European mining technology and training methods. The 20-year-old was an electrical craft apprentice at Sutton Manor Colliery and went on the trip with other NCB apprentices and trainees from all over the country. As well as a manager each pit had its own undermanager, with Teddy Catterall and Ronnie Pearson serving in that position during this period. The main surveyor at Sutton Manor at this time was John R. Allcock, with Keith Halliwell serving as his deputy.

It was revealed in May 1973 that Sutton Manor’s average coal output per manshift during the past year had been 33 cwt. This level of productivity wasn’t considered bad but it was 11 cwt less than the output of Bold Colliery. On May 4th the St.Helens Reporter described how a £200,000 boost would give Sutton Manor Colliery a new lease of life and save it from closure. The NCB planned to use the cash injection to exploit virgin reserves at Barrows Green. This would boost production by almost 2,000 tons a week, from what was then 350,000 tons a year to £460,000 tons. Twin 1,150 yard roadways would be driven through a major geological fault to get at 6 million tons of high quality coal in three seams. Peter Tregnelles, Director of NCB North-Western Area, said:

The energy waves created by the explosions hit different bands of rock of varying density and the resulting pulses were analysed by computer. The technique was not new, having been used widely in the past for oil and gas exploration. The article added that mining engineers would soon be sinking a borehole into the coal measures to take quality samples.

In January 1974 George Robson, who had served as branch president of the NUM at Sutton Manor, retired. At a farewell presentation Roy Jackson, secretary of the Sutton Manor Branch, said: "George lost an arm in a pit accident but I have seen him load a thousand boxes of coal a shift despite the handicap." Mr Robson retired after 42 years in the mining industry.

On January 13th NCB Chairman Derek Ezra described how on a visit to Sutton Manor he had witnessed volunteers manning the boiler house and having to operate the steam engines that powered the winching gear. This was because an overtime ban had been introduced by the NUM two months earlier in pursuit of a wage claim. Ezra also said that the overtime ban meant that underground workers were having to be laid off for two days, while winding cables were replaced.

The coal board was bound by law to replace these cables every three years, but the work would normally be done at Sutton Manor during weekends. Ezra had a 30-minute tour of the colliery with its General Manager Ted Hart and Production Manager Gordon Gillatt and later at a press conference praised the management staff volunteers who were undertaking important maintenance and safety work.

On January 24th 1974 NUM members nationwide participated in a strike ballot over their pay claim. On the following day the Liverpool Echo published a lengthy article on Sutton Manor Colliery and the "tremendous bitterness" that existed amongst the miners and the local community. Coalface chargeman Harry Hulmes had worked at Sutton Manor for 22 years and told the Echo that the miners' claim should be met because of the conditions they worked under and the danger to health. "I am only 38, but I have already got a bad chest.", he added. 55-year-old Sid Glover of Tennyson Street said:

Later in 1974 a new 10-ton triple drilling rig was introduced that was said to resemble a mechanical octopus. It replaced the traditional hand-held drills in penetrating the new reserves and was the first in use within the Western coal field. The eight-strong-team of operators were trained on the new machine in Cornwall and overman Jack Ditchfield from Haydock told the St.Helens’ press how delighted he was with it:

It was a wonderful opportunity to get away from the dirt and grime of the pit in the company of fifty other mining families from all over the UK. This group picture (above) was taken in a Black Sea resort with 11-year-old Jane sat on the front row 3rd left next to her mother and enjoying three weeks off school! Sutton Manor miners were selected from a rota and had to be members of the union to qualify for the holiday.

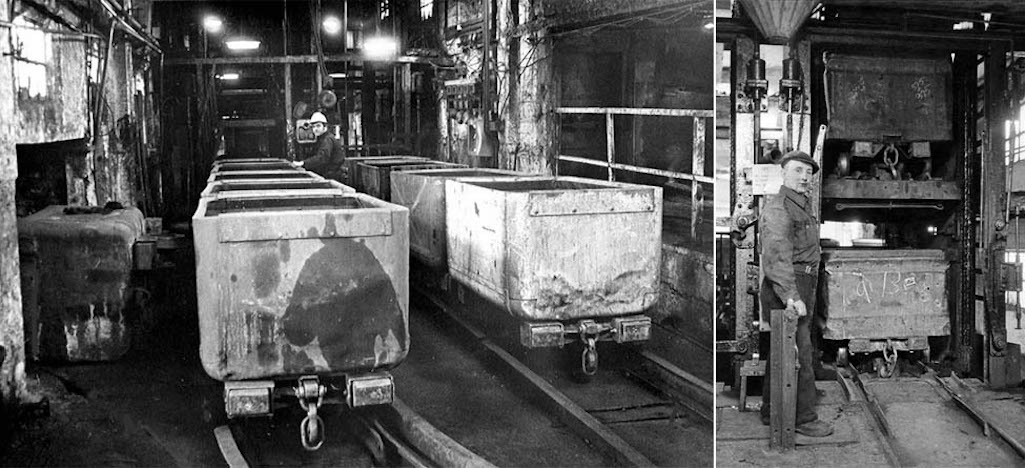

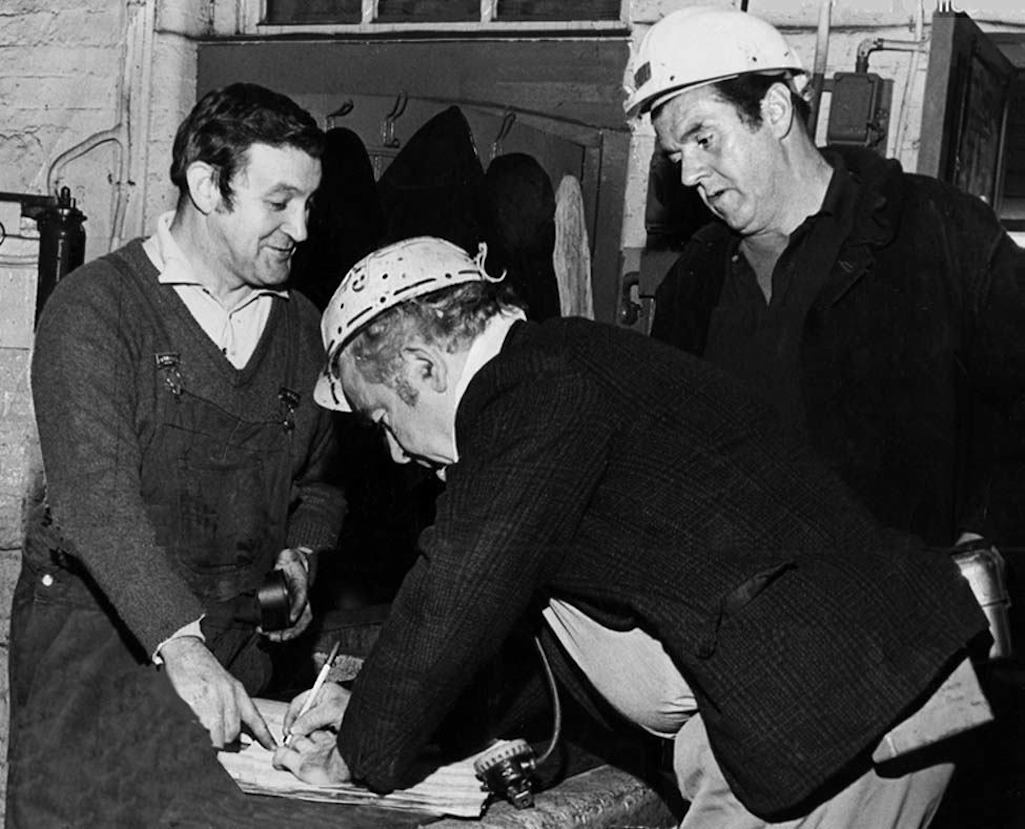

NUM President Joe Gormley at Sutton Manor Colliery (Contributed by Alf Houghton / Mel Moran Collection)

NUM President Joe Gormley pictured at Sutton Manor Colliery

Joe Gormley at Sutton Manor Colliery

Group of St.Helens police officers who visited Sutton Manor Colliery in 1976 with three mineworkers

St.Helens policemen who visited Sutton Manor in 1976 with three mineworkers

Group of St.Helens police officers who visited Sutton Manor in 1976

It was reported in March 1976 that a 2-year-old mining record had been beaten at Sutton Manor Colliery. Coalface teams had set a new overall face productivity record of 220.8 cwt. per manshift. This was four cwt. higher than their previous best performance of 216.5 cwt. That had been established in May 1974. Working two faces in the Higher Florida and Wigan four-foot seams, the men produced 7,309 tons during the record week.

In June 1976 it was reported that 2,000 Sutton Manor Colliery miners and their families had signed a petition protesting against plans to close the accident unit at St.Helens Hospital. They were worried that vital minutes could be lost taking pit accident victims to Whiston Hospital instead. In November it was announced that a six-year-old productivity record had been broken with a record weekly output of 10,670 tons, over 2 cwt higher than in 1970.

In January 1977 some long-serving Sutton Manor and Bold miners were sent on a pre-retirement course at the industry’s Old Boston training centre. This was intended as a pilot scheme for the National Coal Board and was believed to be the first of its kind in the country. More than 20 veteran pitmen, who were approaching retirement age volunteered for the 16-hour course, which provided advice on pensions, benefits insurance, tax and even the need for active interests upon retirement.

The classes were run by senior training officer, Percy Davies and course tutor Bob Howarth and impressed 62-year-old Sutton Manor miner John Clark, who said he wanted to return for more. In January 1978 the NCB announced a local incentive agreement with the Manor men. Such productivity deals were opposed by union leader Arthur Scargill but could mean up to £40 extra pay for underground workers at the colliery.

This history of Sutton Manor would not be complete without describing the volunteers who served as the colliery's firefighters. The significant dangers from a fire at a colliery cannot be over emphasised and after nationalisation a drive took place to ensure that each colliery had the best equipment. This was to be operated by a highly trained staff, supported by a professional full-time fire officer. As well as dealing with on site incidents and undertaking training, the team of firefighters at Sutton Manor competed in the annual Fire Brigades' competitions, which were open to teams from factories and pits.

On July 13th 1968 Sutton Manor Colliery’s volunteer fire-fighting team were pictured in the St.Helens Reporter, having won five cups, two shields, diplomas and individual awards in competitions held over a six-week period. Pictured were Robert Ball, Roy Smith, Derrick Heaton, R. Edwards and fire officer Billy Saunder. On September 14th the team won the Montgomery Trophy, competing at the headquarters of the London Fire Brigade. It was the first time that a team from the North West had won this event, beating 36 other teams from various industries from all over the country.

The award-winning Sutton Manor Colliery firefighting team (Mel Moran Collection)

The award-winning Sutton Manor Colliery firefighting team

Sutton Manor Colliery firefighting team

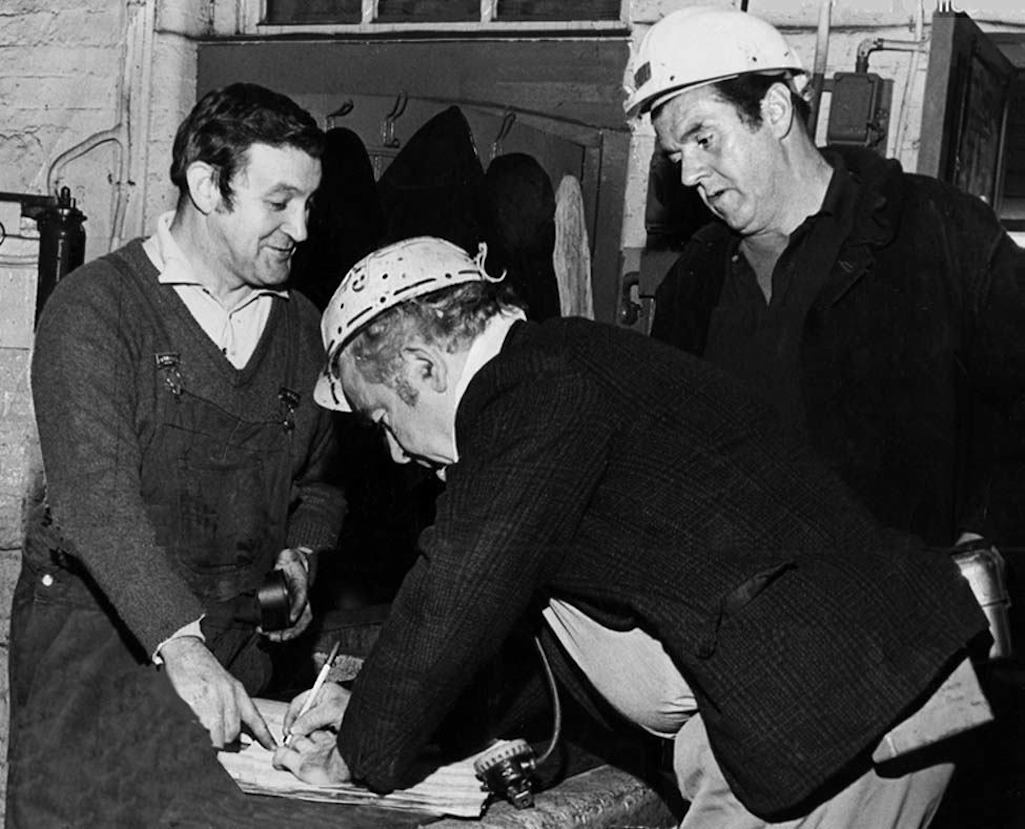

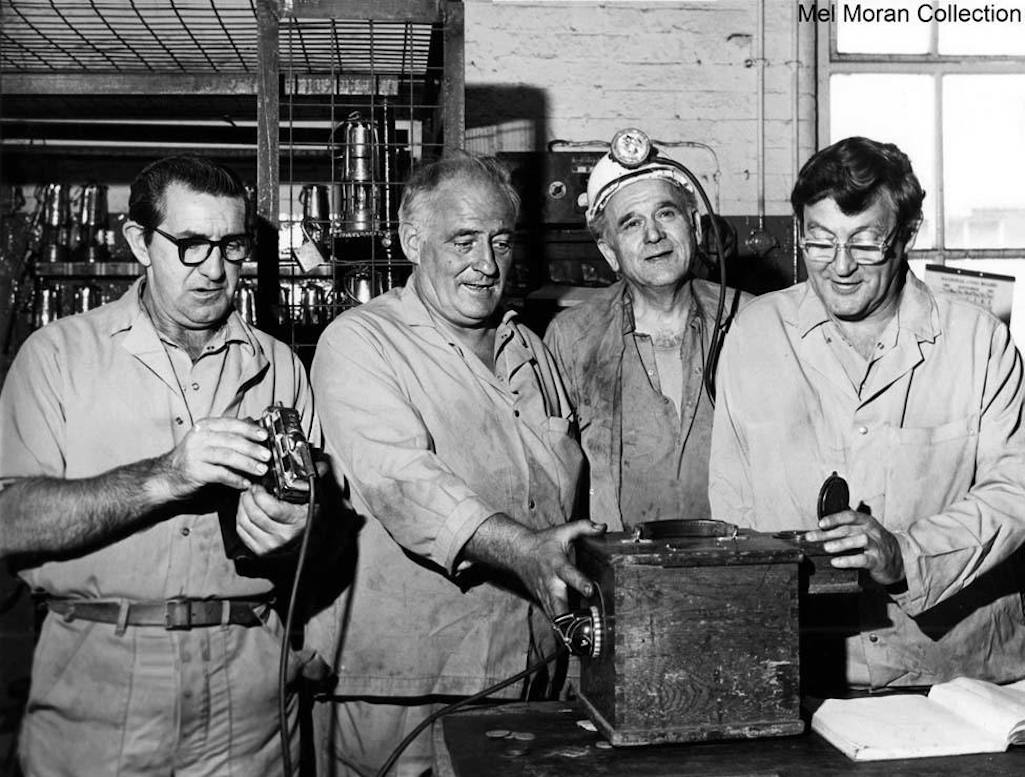

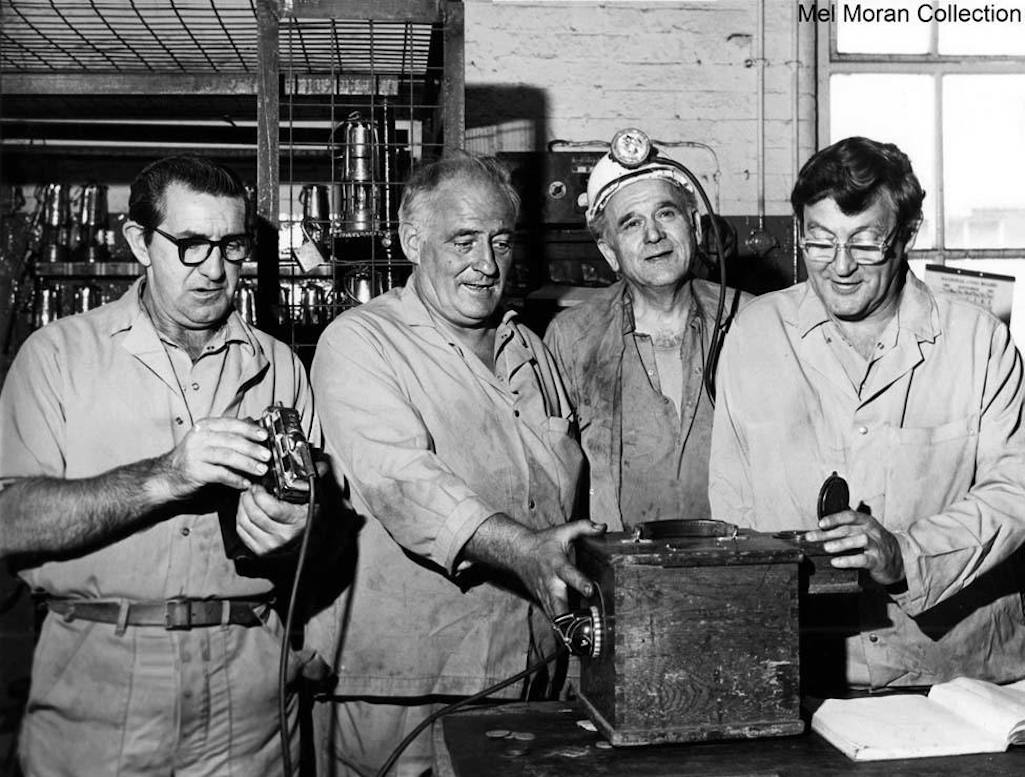

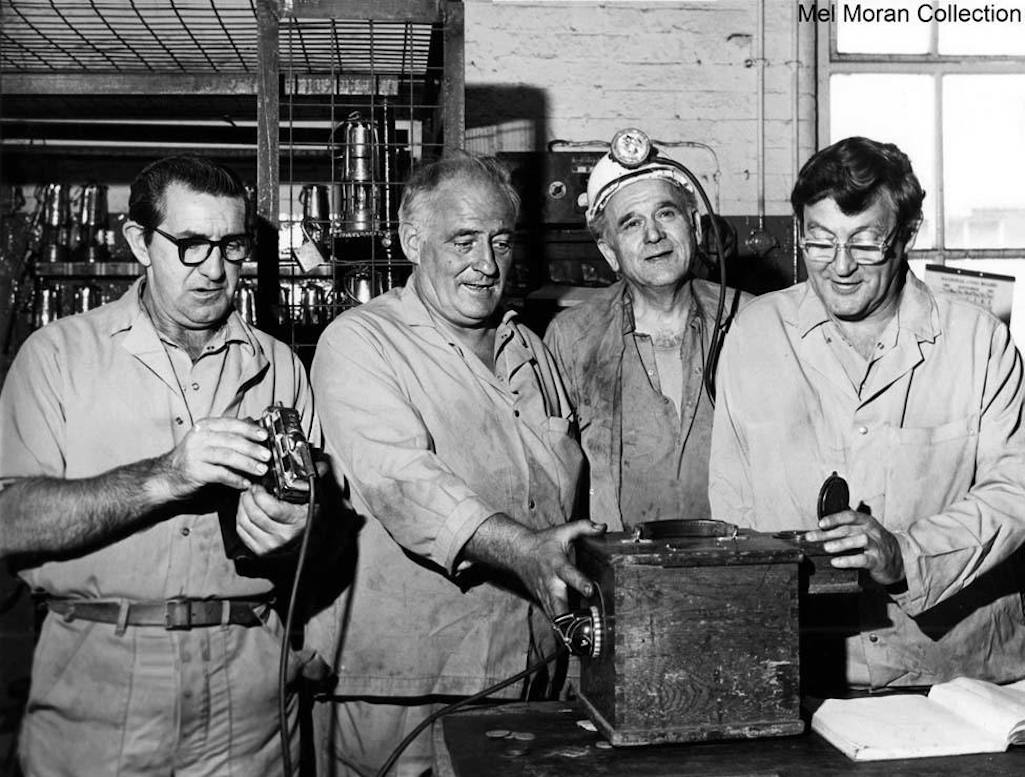

The Sutton Manor colliery lamp room team in 1981 examining lamps prior to their deployment down the pit (Mel Moran Collection)

The Sutton Manor colliery lamp room team in 1981 examining lamps

The Sutton Manor colliery lamp room team in 1981 examining lamps

Lampmen Bob Mellor and Alf Houghton

In the Liverpool Echo on June 4th 1981 was a photo of the colliery's 7-a-side rugby league team after they'd beaten Parkside to win the Coal Board North West competition for the fifth year in a row. The Sutton Manor team had got to the final after beating teams from Parsonage, Bold and Cronton Collieries. Pictured with the cup after their win were Stephen Whitfield, Ray Livesley, Steve Hunt, Stephen Bourhill, John Wills, Bill Johnson, Garry Irvine and Paul Barrow. The team was coached by colliery safety officer Bill Irvine, who was also a coach to the Blackbrook Amateur Rugby League team.

In 1982 the colliery announced its intention to sell surplus methane gas to the ICI Pilkington Sullivan works at Widnes. A 5 mile-long pipeline linked Sutton Manor with ICI and over five million therms of methane - equivalent to three million gallons of oil - was pumped through it. Cooling, distribution and pumping facilities were sited at the colliery and filtration and metering equipment was situated at ICI. The scheme cost £3 million and began on July 14th 1983.

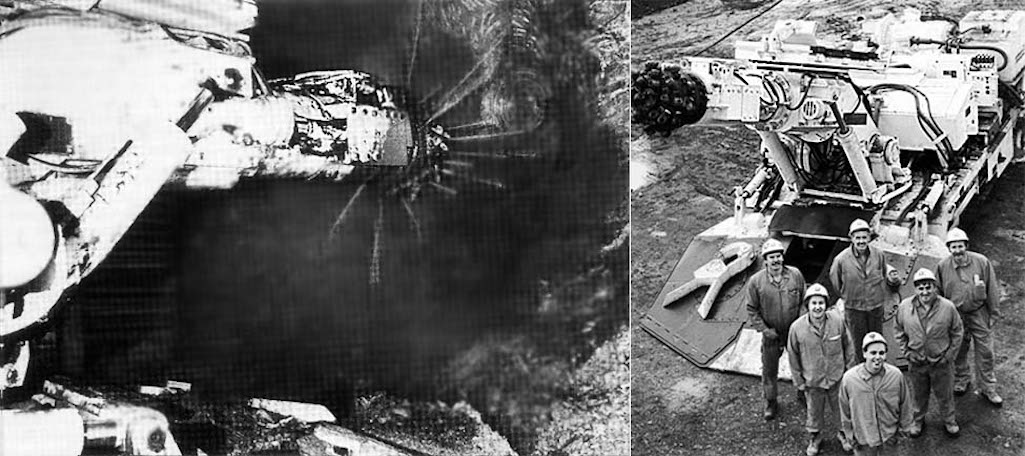

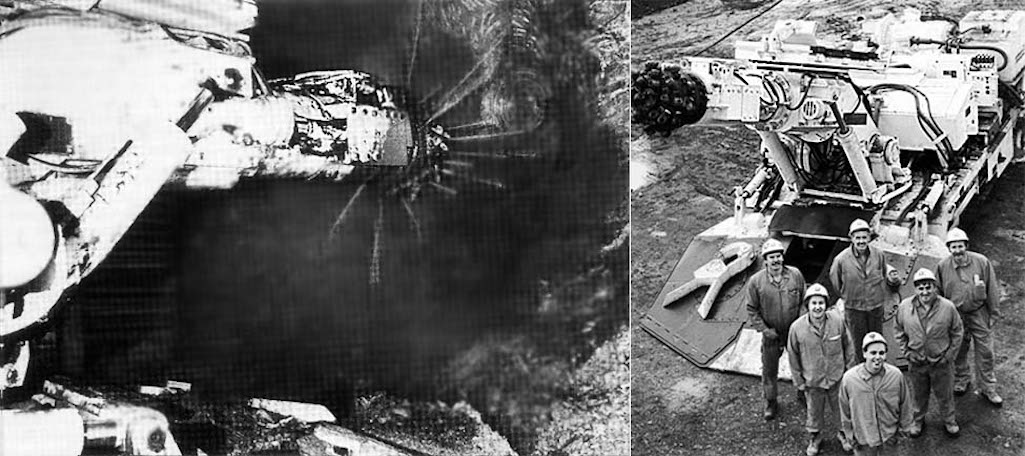

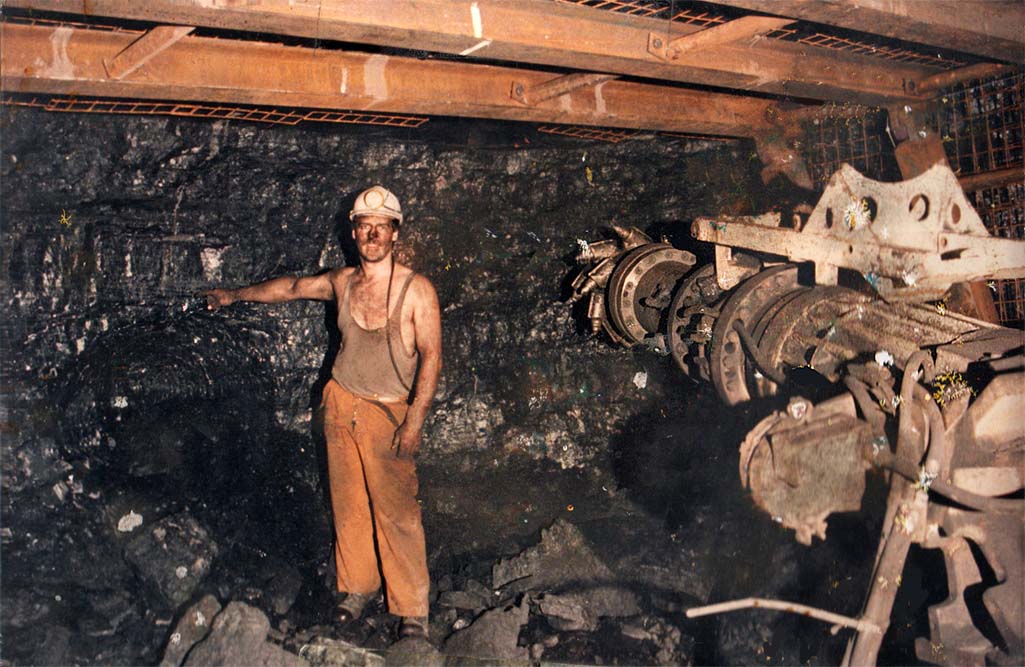

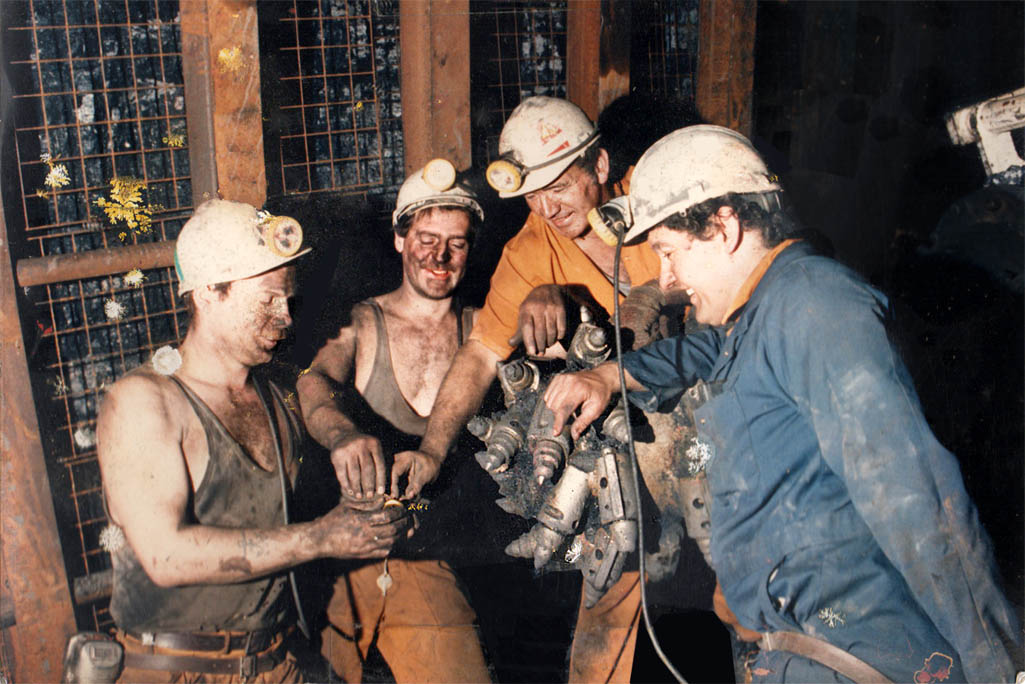

Also that year Sutton Manor Colliery was chosen to undertake the first underground trials of a high pressure water assisted roadheader machine. Water had long been used in mines to reduce coal dust and prevent frictional sparks. The former impaired miners' visibility and had serious health risks, while the latter could cause explosions. Initially the method of application was somewhat crude using hand-held hoses, which was somewhat hit and miss. Over the years the means of deploying water in mining operations improved considerably, although its effectiveness was often curtailed by severe limitations in the water supply.

By the 1980s it was appreciated that the quantity and pressure of the water were vital factors for an efficient deployment. So purpose-built machines were designed, complete with large water tanks. Some early trials were conducted at the limestone mine at Middleton. These led to Anderson Strathclyde developing an RH22 High Pressure Water Assisted Roadheader in early 1983. Roadheaders were excavating / tunnelling machines with boom-mounted cutting heads, which had first been employed in mining during the 1950s.

Two views of the RH22 High Pressure Water Assisted Roadheader at Sutton Manor Colliery

Two views of the RH22 High Pressure Water Assisted Roadheader

RH22 Roadheader at Sutton Manor

The trials lasted six months ending in March 1984 and were largely successful, especially when the RH22 was used at the highest water pressure. The cutting rate increased by 50%, there was no frictional sparking, energy consumption was reduced, machine vibration was minimised, visible dust was virtually eliminated and respirable dust was cut by half. On the negative side the total advance of the roadheader over the 28 week period was only 222 metres. However this was caused by many teething problems that had to be solved during the trial period, as well as through an overtime ban. An impressive 19.62 metres was, however, achieved in a single week towards the end of the six months, which boded well for the future.

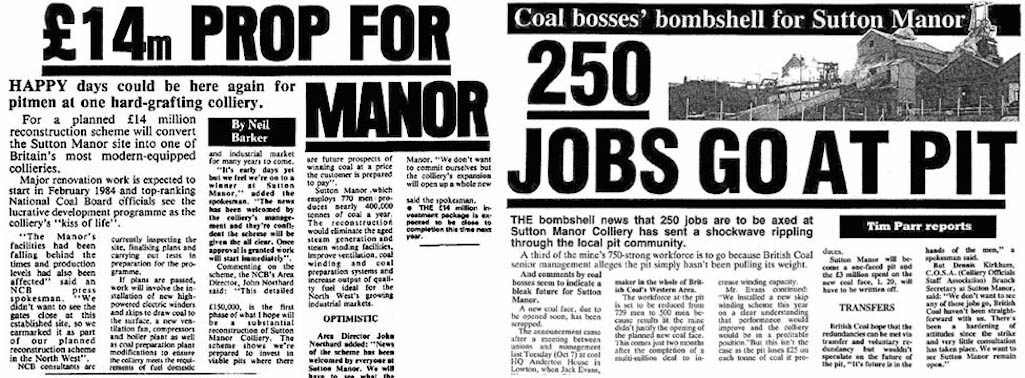

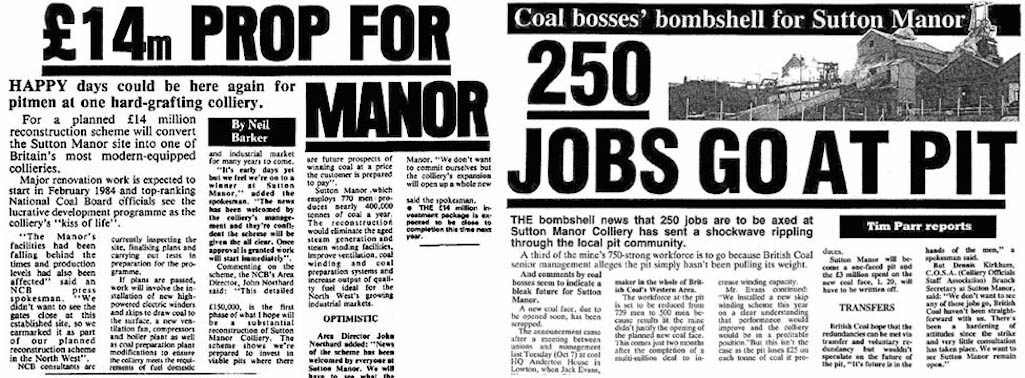

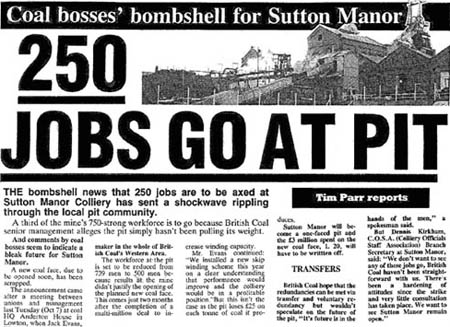

St.Helens Star newspaper articles on Sutton Manor Colliery in St.Helens published December 15th 1983 and October 9th 1986

St.Helens Star articles on Sutton Manor Colliery published in 1983 and 1986

St.Helens Star October 9th 1986

There were also collection centres in Hardman Street and at the Liverpool Seamens' Offices. For almost a year the Printers Union took Sutton Manor miners to a local cash and carry to buy fruit, bacon, eggs and vegetables. Every week a man, who no one knew, turned up at the Sutton Manor Institute with a large bag of carrots and one of onions.

For the children of the strikers, the free school dinner was a lifeline that served as their main meal of the day and the community also ensured that the youngsters had an annual Christmas party. On August 23rd 1984, 200 children from Sutton Manor families got away from the hardship of the strike through a day in Blackpool. The trip was funded by the NUM and businesses, who provided specially reduced rates. There were also large reductions made by Blackpool Tower and the Winter Gardens, where meals and a disco were enjoyed.

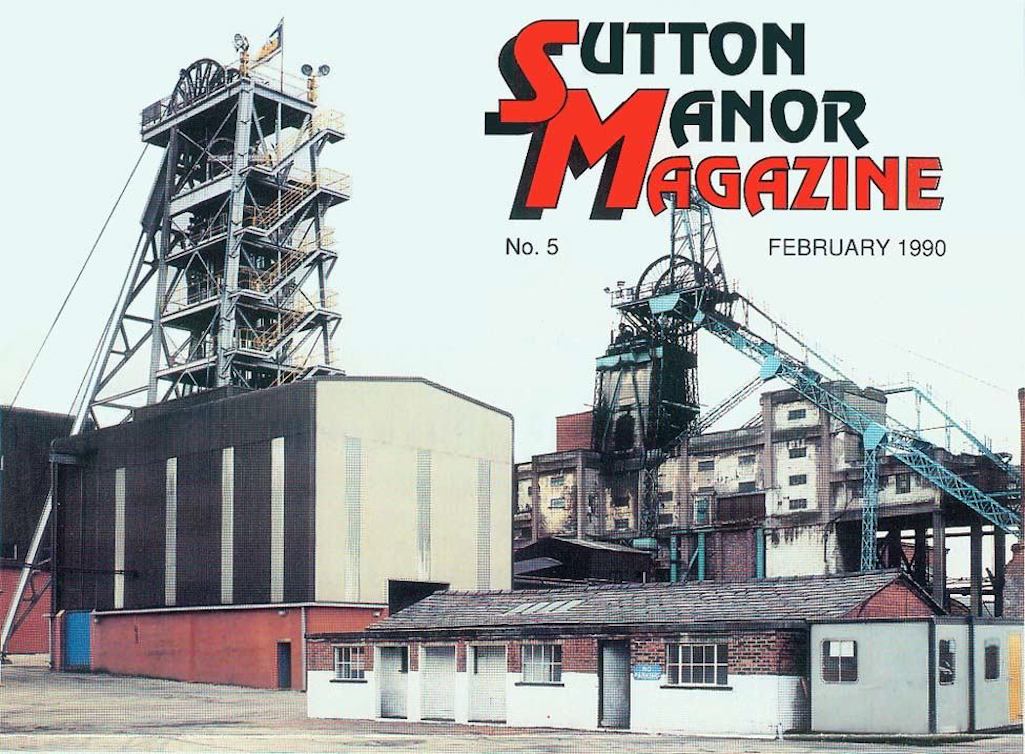

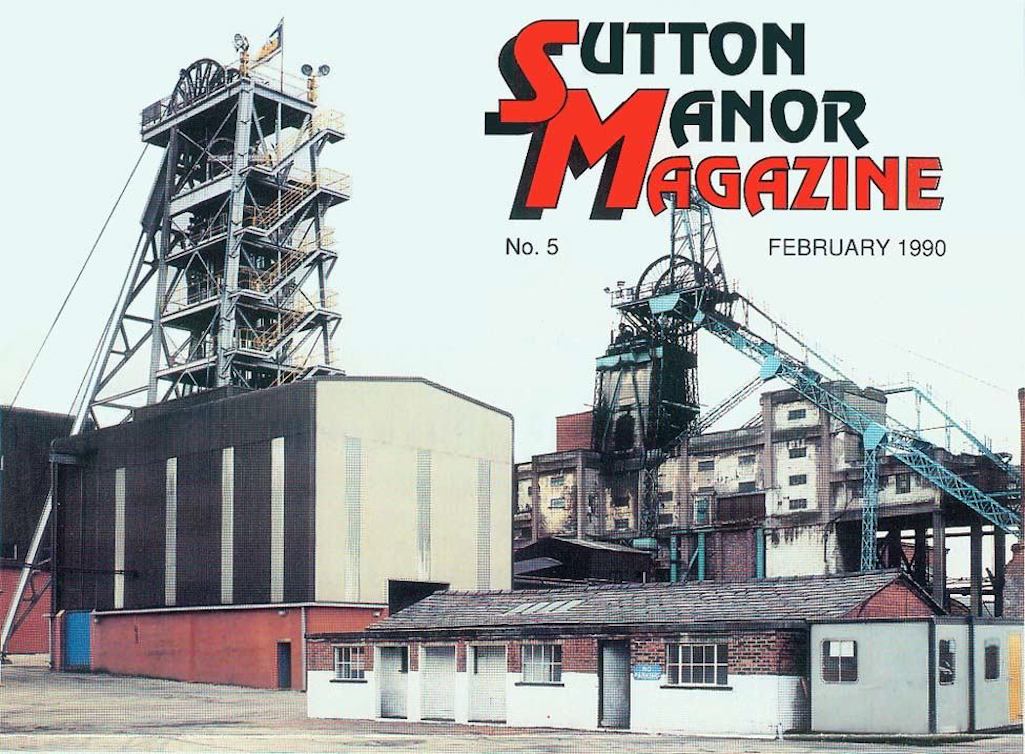

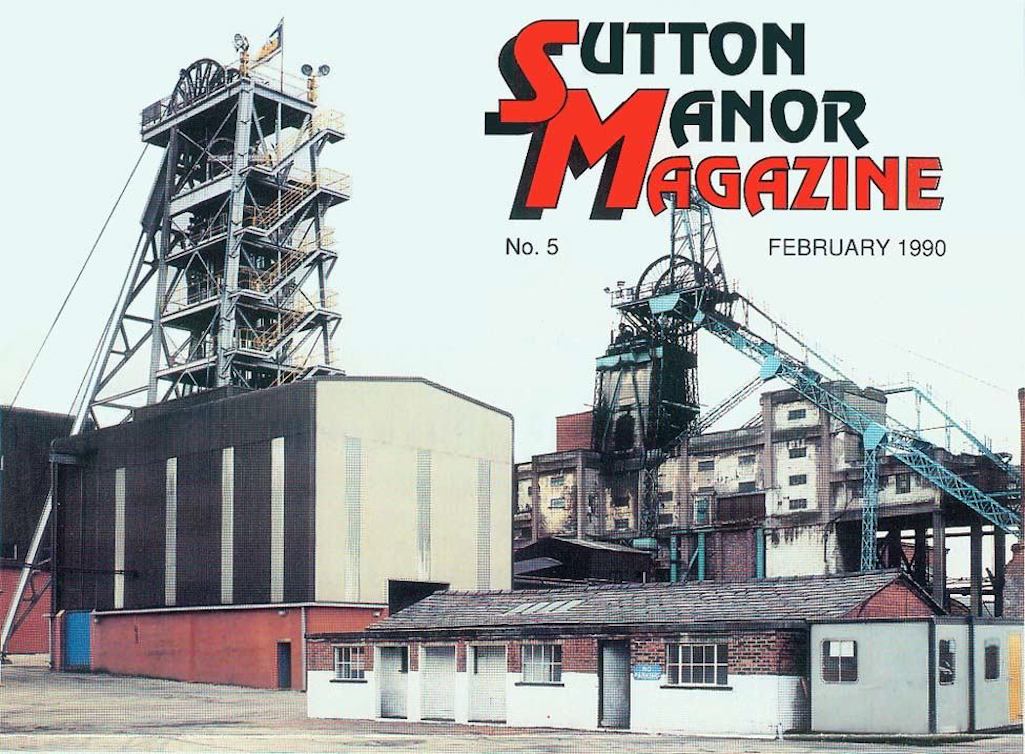

Sutton Manor Colliery on the front cover of British Coal's in-house Sutton Manor Magazine

Sutton Manor Colliery in British Coal's in-house Sutton Manor Magazine

The colliery in Sutton Manor Magazine

However only a quarter of its 800 miners were working, compared to the Lancashire average of 58% with 77% employed in the whole Western area. As production resumed, NCB Western Area director John Northard announced that the investment planned for Sutton Manor had risen to £17.4 million. The three-year modernisation programme, would, said Northard, turn a consistently and heavily-loss-making pit into a profitable one, although there would be a slight reduction in labour. The improvements would entail a new electric winder, new ventilation fan, compressors and boiler plant, as well as modifications to the Coal Preparation Plant. It was claimed to be the biggest ever investment page in a North West pit.

On January 14th 1985 Manager Peter Earnshaw wrote to all still on strike outlining the £17m investment package and stating that 330 men were now back at work. A tax-free payment of more than £2000 was on offer to men who returned to Sutton Manor ending with the plea: “Finally, why not start 1985 by putting the strike behind you and join your mates back at work.” Advertisements were also placed in St.Helens newspapers inviting strikers to return, again telling those who were still out that ‘Your mates are back’. Unfortunately not everyone at Sutton Manor could still be described as mates after the strike ended in March.

Aerial plan of Sutton Manor Colliery with photograph by Ian Lally - see below for details

Aerial plan of Sutton Manor Colliery with photograph by Ian Lally

Aerial plan of Sutton Manor Colliery

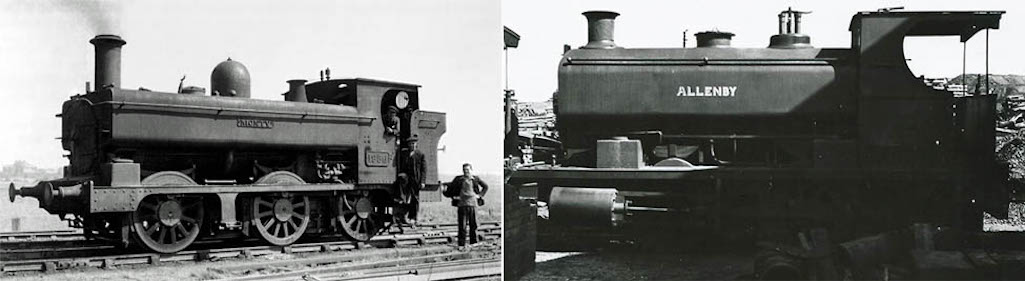

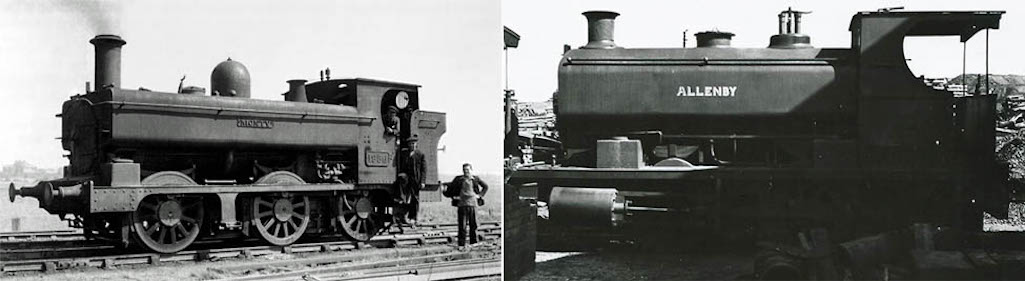

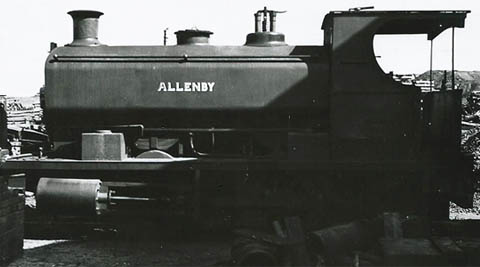

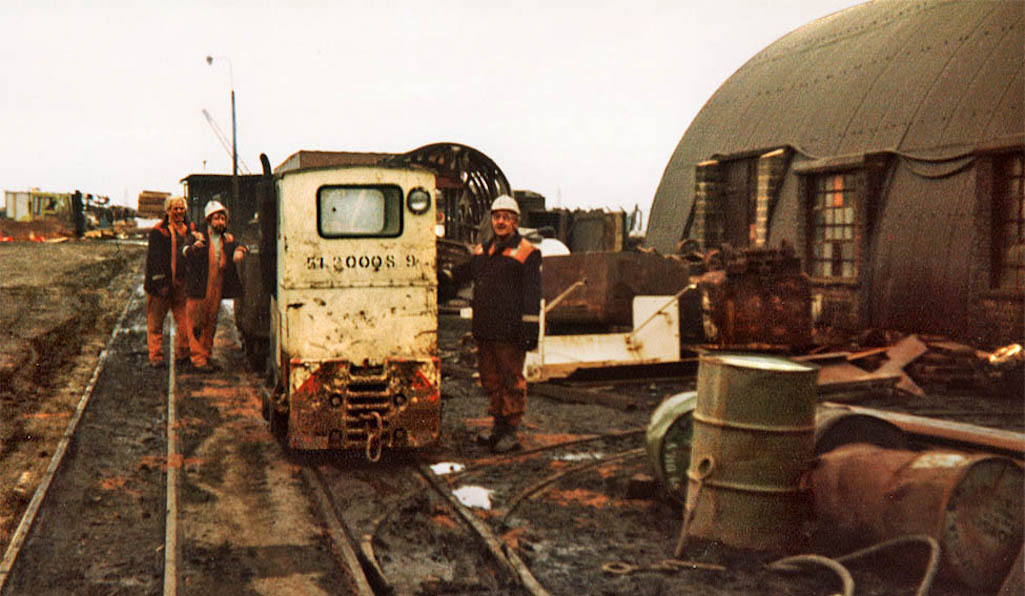

Soon after the ending of the strike in 1985, coal distribution by rail ceased at Sutton Manor with transport made by road instead. Over the years a number of locomotives served the colliery, with one of the first being a four-coupled steam engine called Samson, which was broken up in WW1. In 1908 a saddle tank called Ajax was acquired from Andrew Barclay of Kilmarnock, which after the war was renamed Haig. Barclay’s also supplied Allenby in 1919 and this and Haig were responsible for pulling all Sutton Manor’s wagons until Monty arrived in 1940. Originally known simply as no. 1956, Monty was quite an old engine having been built in Wolverhampton in 1888.

Left: Monty (formerly no. 1956) which arrived at Sutton Manor Colliery in 1940; Right: Allenby in 1948

Left: Monty which arrived at Sutton Manor in 1940; Right: Allenby in 1948

Loco Allenby at Sutton Manor in 1948

Around this time the colliery ceased using its private railway to the Liverpool and Manchester line at Lea Green, with all coal subsequently sent over the St Helens and Widnes line. During the 1960s Sutton Manor continued its mix of steam and diesel locomotives, with steam engine Amazon acquired in 1964 and another diesel loco arriving from Chisnall Hall Colliery three years later. However diesel became increasingly used and as the need for shunting work decreased at Sutton Manor, just one loco was in daily use.

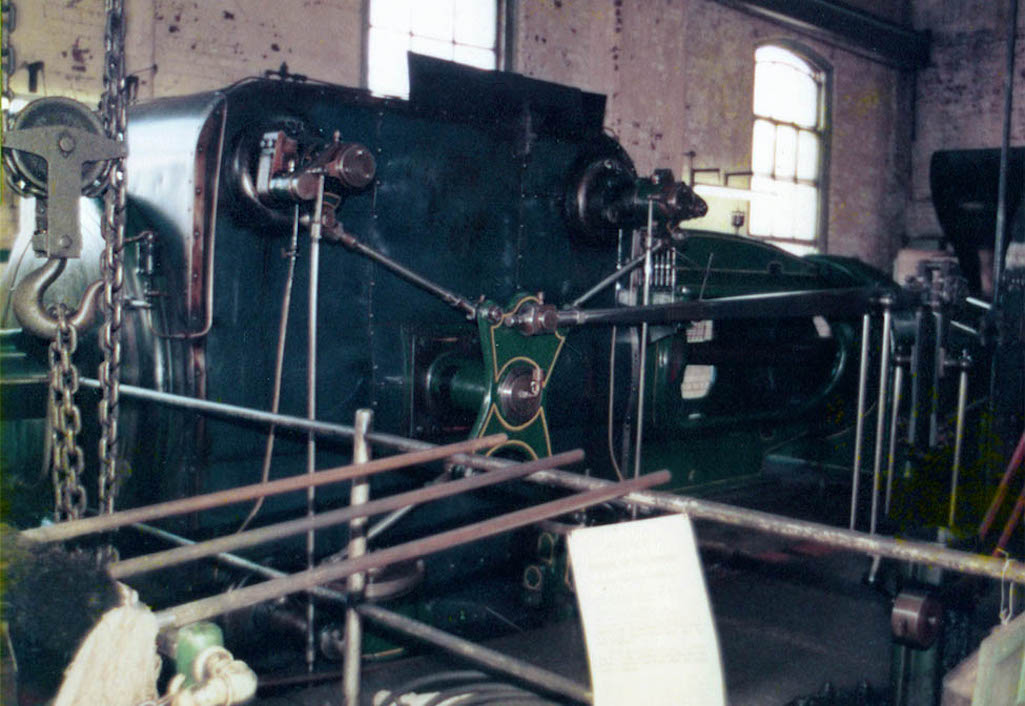

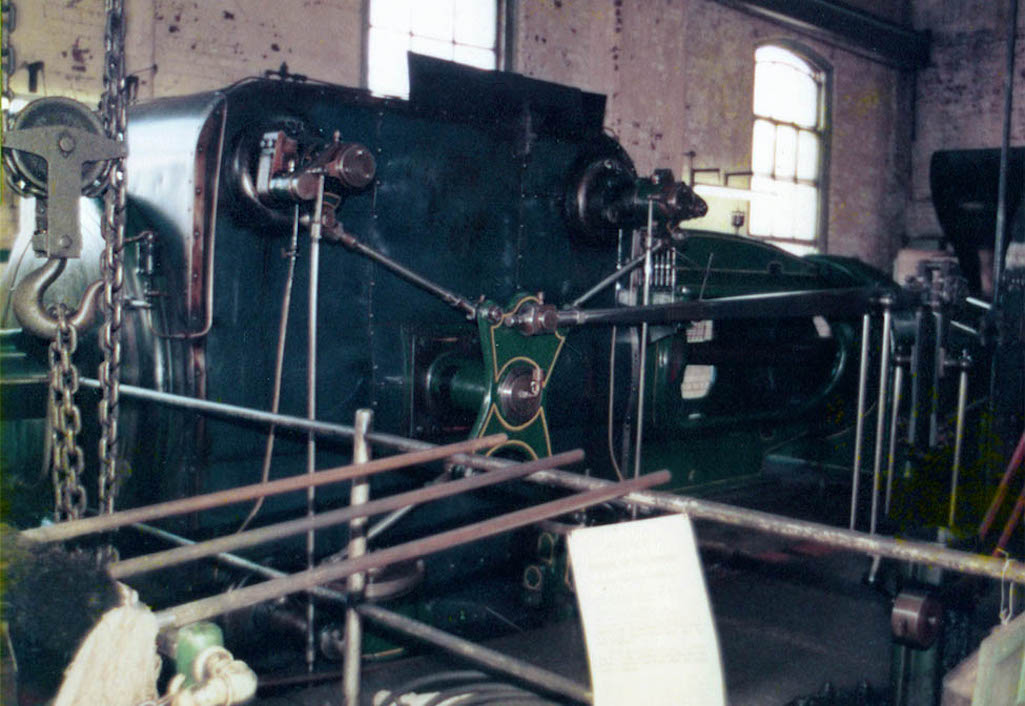

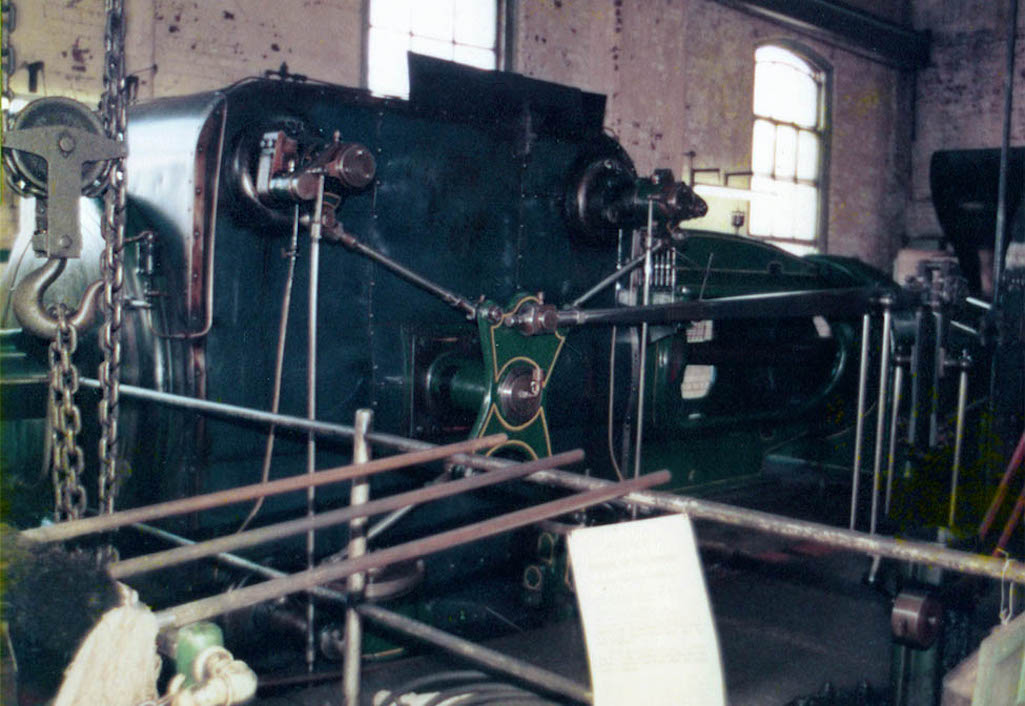

The steam engine at Sutton Manor Colliery which powered the No. 2 shaft’s winder (John Oates Collection)

The steam engine at Sutton Manor which powered No. 2 shaft’s winder

No. 2 shaft’s steam engine at the colliery

On May 20th at a meeting of Bold Parish Council, George McNicholas, a deputy at Sutton Manor, declared that contrary to rumours the colliery would still operating in forty years time. This was during a discussion about water from one of the coal faces, which had been flooding the top of Abbots Hall Avenue in Sutton. After the meeting Councillor McNicholas said: “We have antiquated machinery that will be replaced by August and will help us to make the pit more profitable”.

During the Spring and Summer of 1986, the NCB's successor, British Coal, electrified Sutton Manor's No. 1 shaft steam winder, leaving the No. 2 shaft winder in its original condition of steam. Sutton Manor colliery was, for a time, unique in possessing one of the newest electric winding engines, as well as having one of the oldest in number 2 shaft's steam winder. In fact it was the last colliery in the country to use steam as the St.Helens Reporter had reported eight years earlier:

Work to electrify the no.1 pit's steam winder and shaft at Sutton Manor colliery by Qualter Hall in 1986

Work to electrify no.1 pit's steam winder and shaft by Qualter Hall in 1986

Work to electrify the no.1 pit's steam winder and shaft during 1986

The new work was undertaken by engineering consultant's Qualter Hall & Co. of Barnsley and the opportunity was taken to replace the old coal tubs with modern skips, which upon reaching the surface were emptied onto a conveyor system that led to washery screens. As a result of the electrification, No. 2 shaft now became the primary shaft for winding and transporting men and materials. However there were no changes of mine ventilation with No. 1 continuing as the downcast shaft and No. 2 shaft as the upcast.

Photographed in August 1986 the new no.1 headgear and the no.2 headgear at Sutton Manor (Mel Moran Collection)

Photographed in August 1986 the new no.1 headgear and the no.2 headgear

The new no. 1 headgear and the no. 2 headgear at Sutton Manor Colliery

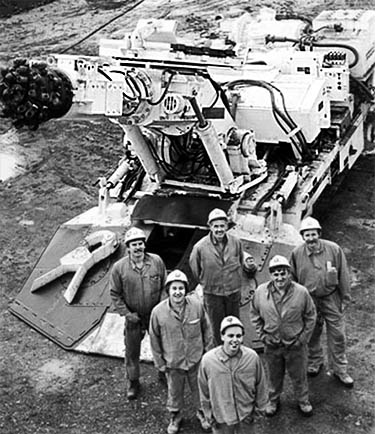

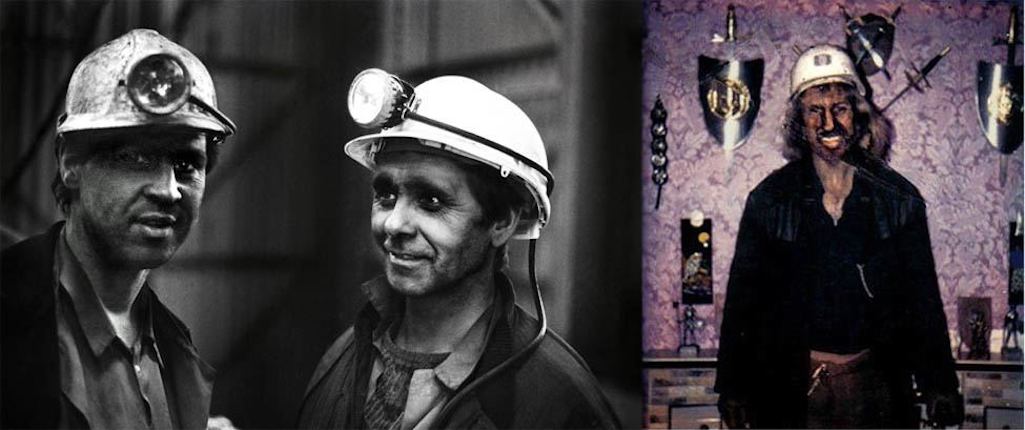

Gilford, top dog of the Sutton Manor Colliery lamp room, with his pitmen pals in June 1988

Gilford, top dog of the Sutton Manor Colliery lamp room, with his pitmen pals

Gilford the lamp room dog in 1988

The warning was quickly heeded and by December 1986 British Coal was able to announce that productivity had reached an all-time high of 3.7 tonnes per man. This was one tonne above the previous record that had been set in 1976. At the same time a new coal face productivity record was claimed of 22 tonnes per manshift, almost two tonnes better than previously. Manager John Warwick said they had some of the best quality coal in the Western Area and called for a consistently high performance from the Manor men, in order to prove to British Coal that the colliery can be relied upon to produce coal at the right price and in the right quantities.

This photograph from the 1980s was taken from Jubits Lane and shows the demolition of the Martin Stoker boiler

This photograph shows the demolition of the Martin Stoker boiler

Demolition of Martin Stoker boiler

Western Area Director Jack Evans had set them an output figure of 12,500 tonnes of coal a week and on December 3rd it was revealed that the Manor men had produced 10,026 tonnes during the past week. This was a record - as was the productivity per man-shift figure - but these were still not good enough. NUM Secretary Colin Brown claimed that the production goals were “totally unreasonable, given the circumstances”, with a cutting tool operating on a brand-new face at just three-quarters of its full capacity.

A fortnight later British Coal held a meeting with union representatives and informed them that Sutton Manor would be given more time to prove they could meet ‘realistic’ production targets. Jack Evans said the colliery had been given a “suspended sentence”, rather than a reprieve. But output and productivity did improve and by the end of January 1988 the colliery was making a profit of up to £200,000 a week. The Sunday Times on January 31st wrote that ‘the turnaround in the once-doomed pit is dramatic’, describing how three times as much coal was being produced at Sutton Manor than before the 1984 strike, with less than half the number of men. Their earnings had also increased from a take-home pay of £80 per week to around £130, along with increased productivity bonuses.

In February British Coal said the nationwide dispute concerning the pit deputies union NACODS was the equivalent of an “own goal” for the future of Sutton Manor, as it was likely to affect output. Safety rules meant that pits couldn’t operate without the presence of deputies and so miners had to be sent home when the deputies were on strike or observing an overtime ban. Union secretary Colin Brown said: “We have shown we are capable of meeting their targets but if we cannot get down the mine we cannot produce the coal”.

On June 16th 1988 Manor pitmen Kevin Mather, Bob Baugh, Alan Swift and the aforementioned Colin Brown appeared in the St.Helens Star with their pet pooch Gilford. The dog had wandered into their lamp room some weeks earlier and decided to take up residence. As the animal had been found above ground, it was given the name of the colliery’s surface superintendent. Whether Terry Gilford considered it to be a tribute or insult wasn't recorded!

This was the communication centre for contact with and from all underground districts and was the nerve centre of the colliery. The control room could be contacted by telephone and via an underground tannoy system known as ‘DACS’, after the name of the manufacturer, Derby Automation Consultants. These pictures are part of the John Oates Collection in Sutton Manor Colliery Photo Album 8, with captions and above descriptions and ids by Ken Bailey Jnr.

In August 1988 it was announced that the colliery had broken another productivity record with output breaking through the six tonnes a man barrier for the first time. Output from the pit’s 280-metre long Florida 24s face set a record of 14,550 tonnes, which was more than 1000 tonnes better than the previous best coal face tonnage.

In 1989 Sutton Manor miner Steve Sullivan was made president of the Lancashire area NUM but continued to work on the coal face. Steve had played a leading role in the 1984/5 strike, during which he discovered that he had a talent for public speaking. As an activist he helped to ensure that the majority of Lancashire mineworkers went on strike and that Sutton Manor pitmen stayed out for as long as they did. Sadly Steve died aged just 41 in 1997, after a long fight against cancer.

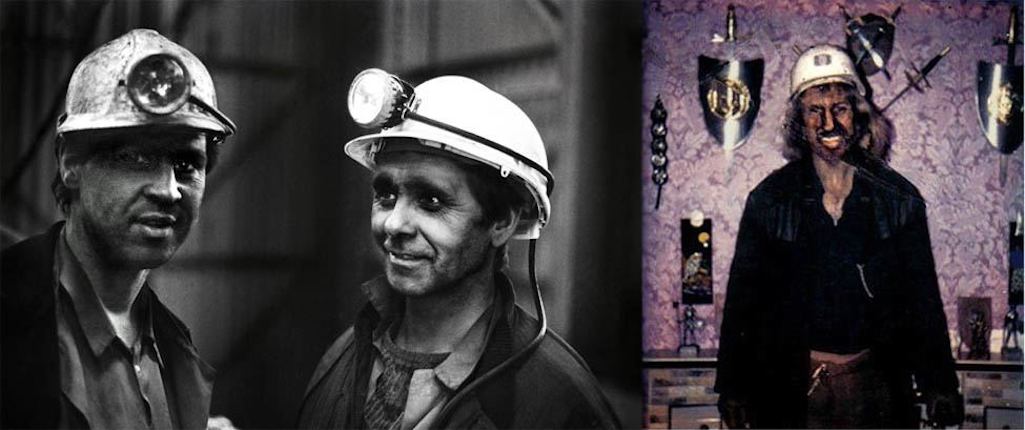

Left: Anonymous Manor miners (Frazier Nairn Collection); Right: Bill Mullaney at his Milton Street home after a nightshift

Manor miners and Bill Mullaney (rt) at his Milton Street home after a nightshift

Unknown Sutton Manor miners

A photograph which appeared in 'Sutton Manor Magazine No.5' published in February 1990

A photo which appeared in 'Sutton Manor Magazine No. 5' in February 1990

This photo appeared in 'Sutton Manor Magazine No.5' in February 1990

On February 1st the St.Helens Star published an article on the production success, which featured a photograph of Sutton Manor mineworkers holding up letters that formed the word ‘CHAMPS’. They wrote: ‘These powerhouse pitmen have hacked away at the record books and helped protect the future of their colliery’. Similar record breaking coal production levels had been achieved in 1988 and in both years a Sutton Manor ‘Record Breakers’ tie was given to all members of the workforce.

Concerns for the future of the colliery were raised again on March 15th 1990 when it was included in a lit of 41 pits that were considered most at risk of closure. In an in-depth report issued by the Coalfield Communities Campaign, economists Stephen Fothergill and Stephen Witt predicted that the Government’s plans to privatise British Coal would lead to the closure of many collieries, causing 35,000 mining job losses over five years.

However British Coal dismissed the forecasts as “no more than guesswork” and Sutton Manor’s NUM Branch Secretary Rod Fraser said that the duo’s comments were “alarmist”, with privatisation actually helping the colliery. This was through an increase in orders for coal from National Power at Bold Power Station and PowerGen at Fiddlers Ferry. Fraser added that Sutton Manor’s coal was extremely high in calorific value with 85% of its output going to power stations.

By December 1990 the Colliery Manager was Peter Redford and in the Christmas edition of 'Sutton Manor Magazine (no. 9) he informed the pitmen that in the quarter that ended in October, output had gone down. He claimed that British Coal had lost money and so Sutton Manor had been put back into the 'Reconvened Review Procedure'. However, the colliery manager also revealed that since October, the week by week tonnage was starting to rise and there was some cautious optimism for the future with Redford also referring to planned development work.

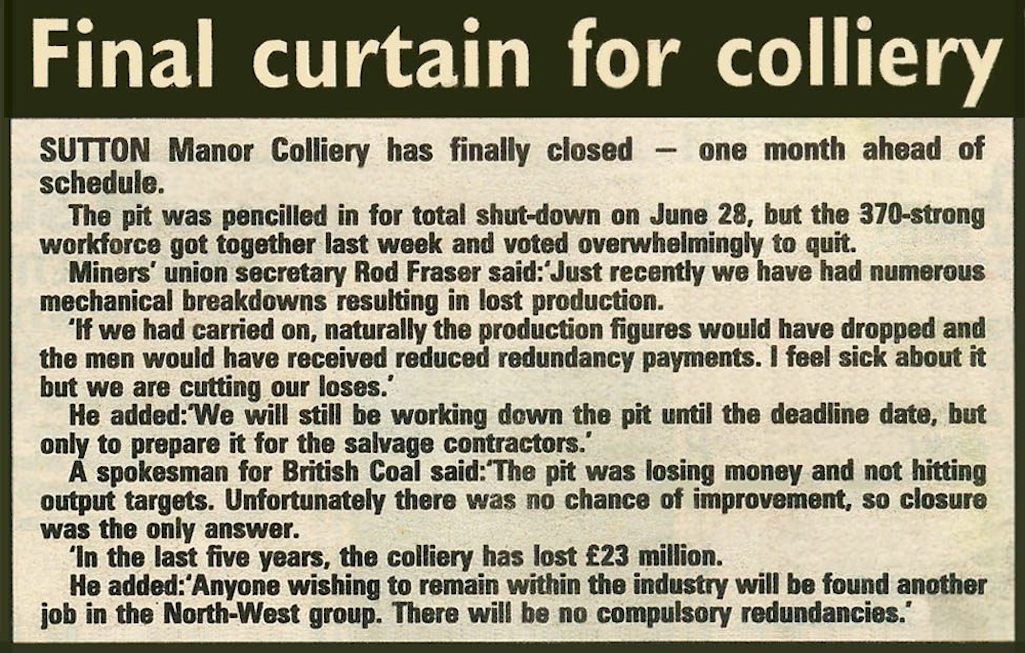

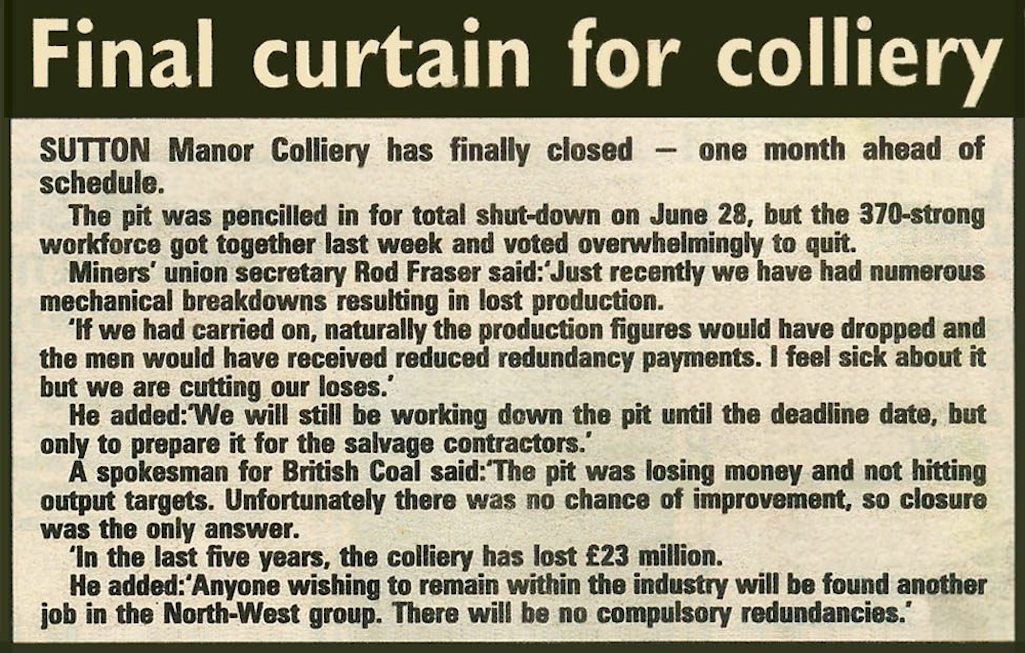

So there was some bewilderment when on March 11th British Coal’s North West Group announced that the pit was unviable and recommended its immediate closure to the Corporation of British Coal. They claimed that Sutton Manor Colliery had lost £23 million over the previous five years, including a loss during 1991 so far of £3.2 million. On the following day members of the local NUM met to decide what action to take.

Branch and Area President Steve Sullivan reported to the media that the men had voted to appeal against the decision. North Group Director Frank Middleton said he hoped there would be no compulsory redundancies and that those of the 450 men at Sutton Manor, including contractors, who wished to continue working for the company would be found work at other pits.

The MP for St.Helens South, Gerry Bermingham, criticised the decision and said he would raise the matter in the House of Commons:

Some left Sutton Manor as NCB employees but then returned working for private mining salvage companies until all the equipment had been removed. By the end of 1992 the whole site had been flattened. Budge Mining (now known as UK Coal) then spent two years with six staff in a mobile washroom, washing the coal that was picked out of the colliery spoil heap.

St.Helens Star report on the closure of Sutton Manor Colliery from May 30th 1991

St.Helens Star report on the closure of the colliery from May 30th 1991

St.Helens Star from May 30th 1991

The old National Coal Board gates in Jubits Lane and the remnants of the pit shafts are all that’s left to remind visitors of the site's illustrious past. After the colliery’s closure, the shafts were filled with stone from the pit bottom up to the first inset. Concrete was then poured in and more stone added up to the next inset, where more concrete was introduced. This process was repeated up to the top of the shaft, where a concrete cap and pipe were added.

The capped pit shafts in Sutton Manor Woodland - The first two images show pit 1 and the third pic is pit 2

Capped former colliery pit shafts within Sutton Manor Woodland

Capped pit shafts in Sutton Manor

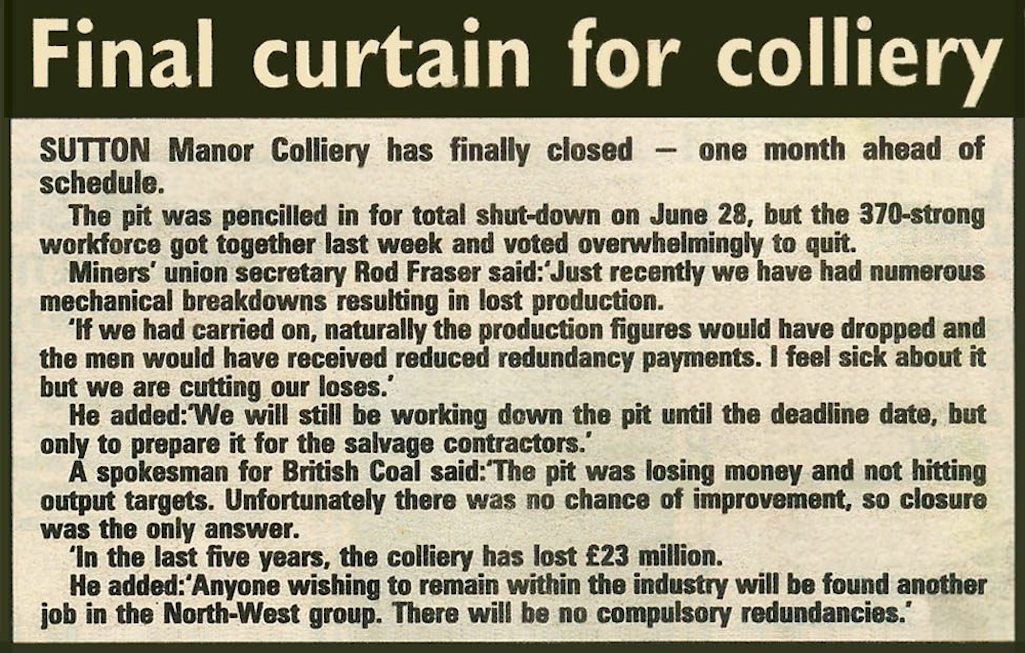

Noah Lamb (1898-1990)

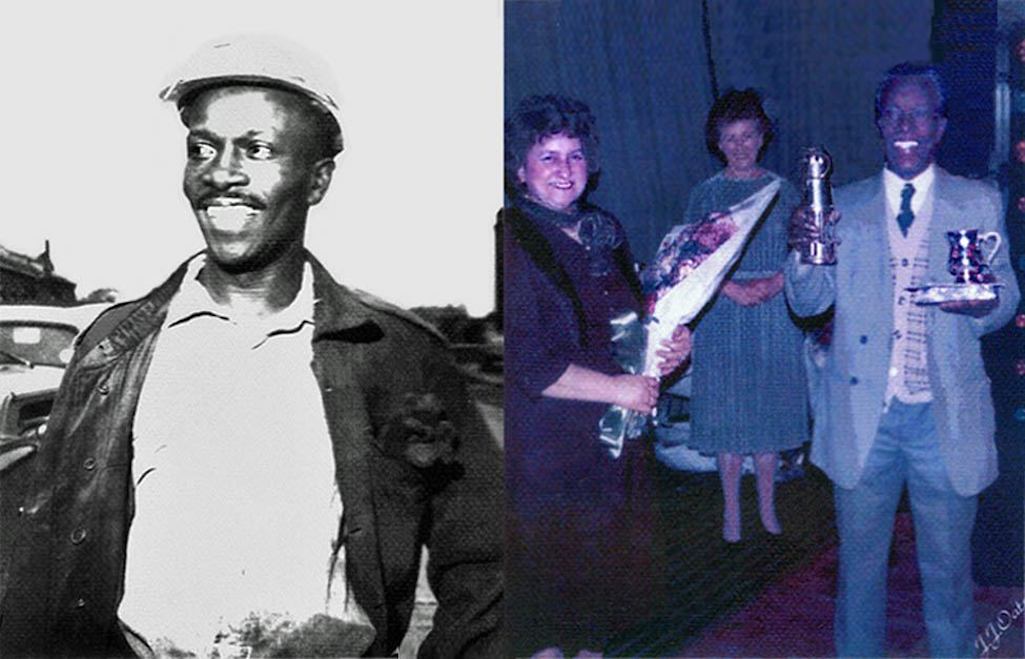

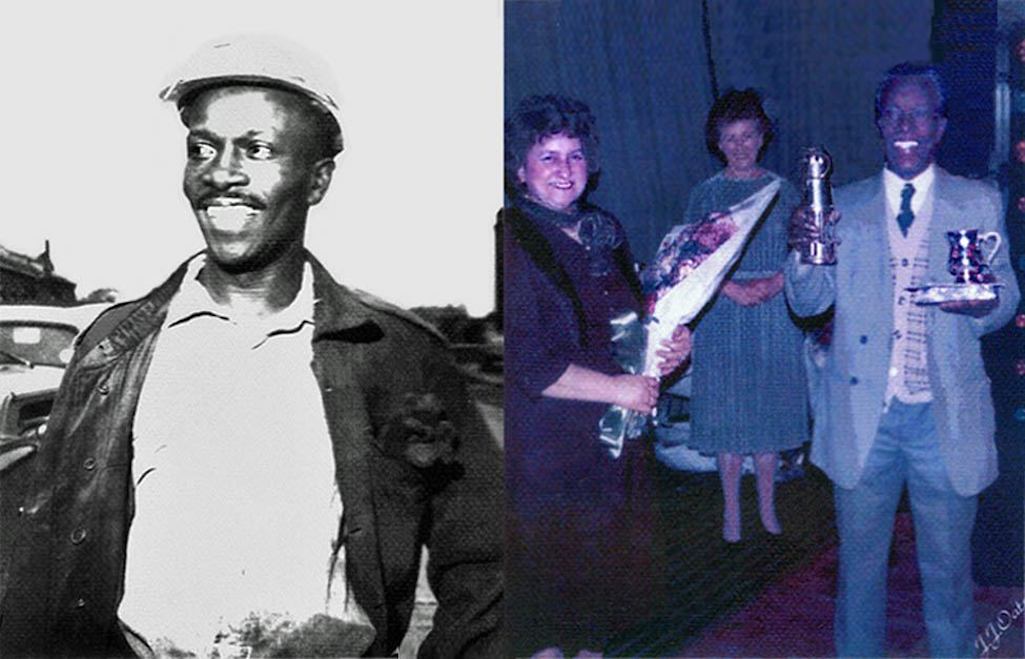

Pit deputy George Streete pictured in 1960 and at his retirement in 1980 (contributed by Esther Streete)

Pit deputy George Streete pictured in 1960 and at his retirement in 1980

Pit deputy George Streete in 1960

A number of former Sutton Manor pitmen became councillors or civic leaders such as Harry Williams, who worked at the colliery for 50 years as a foreman in the power house. In fact his brothers Arthur and Wilfred worked for similar durations and so the trio put in about 150 years combined service at the pit. Harry held the distinction of being the Mayor of St.Helens in 1973, its final year as a borough council prior to becoming a Metropolitan Borough under Merseyside.

Mike McGuire served as MP for Ince from 1964 to 1983 and was then the parliamentary representative for Makerfield until 1987. When at Sutton Manor, McGuire served as full-time branch secretary of the NUM. Dr. Ken Moses CBE from Thatto Heath was a General Manager at Sutton Manor Colliery and later worked as a senior executive at British Coal. Former pitman Brian Spencer was until 2010 the Leader of St.Helens Council.

Ernest Patterson deserves a mention too for his football prowess. The Manor miner of Shakespeare Road played some games for Manchester City in the early 1950s and was scouted by Doncaster Rovers. Alan Durband who became chairman of the Everyman Theatre and a member of Radio Merseyside's Local Broadcasting Council had at one time worked underground at Sutton Manor Colliery.

House and garden of Albert Rigby from Ditton who often won NCB garden competitions - Contributed by Pat Beesley

Garden of Albert Rigby from Ditton, who often won NCB garden competitions

House & garden of pitman Albert Rigby

Post-war many of the mineworkers were proud of their gardens. The NCB held an annual garden competition and there was keen rivalry between neighbours. Pictured above is the home and garden of Sutton Manor pitman Albert Rigby, who lived in one of the Ditton houses. A keen gardener, Albert won the competition or was runner up on several occasions. Pictured in the 1950s prior to smokeless fuel, the houses are soot-stained like many other buildings at that time.

Although there were many improvements in terms of technology and practice during the 20th century, working down Sutton Manor was never easy. Ex-pit man Gary Conley described the conditions on BBC North West Tonight on March 4th 2009, in a report that commemorated a quarter of a century since the start of the 1984 strike: "It was hotter than the flames of hell in some sections and cold as the Antarctic in others."

Despite the often harsh conditions, the bonds of friendship between the workforce, in what's been called a family pit, were very strong. Almost twenty years since the closure, many mineworkers still have a considerable connection to the site. On May 31st 2009 as part of the Big Art Project, a work of public art called Dream was officially opened at the apex of the former colliery's spoil heap, which rises 270 feet above sea level.

This artwork towers over the M62 and was designed by Catalan artist Jaume Plensa both to serve as a memorial for the site's heritage but also to look forward to the future. Appropriately, former Sutton Manor pitmen have played a pivotal role in commissioning this monument to the blood, sweat and toil that took place underneath the statue for eighty-five years of the twentieth century.

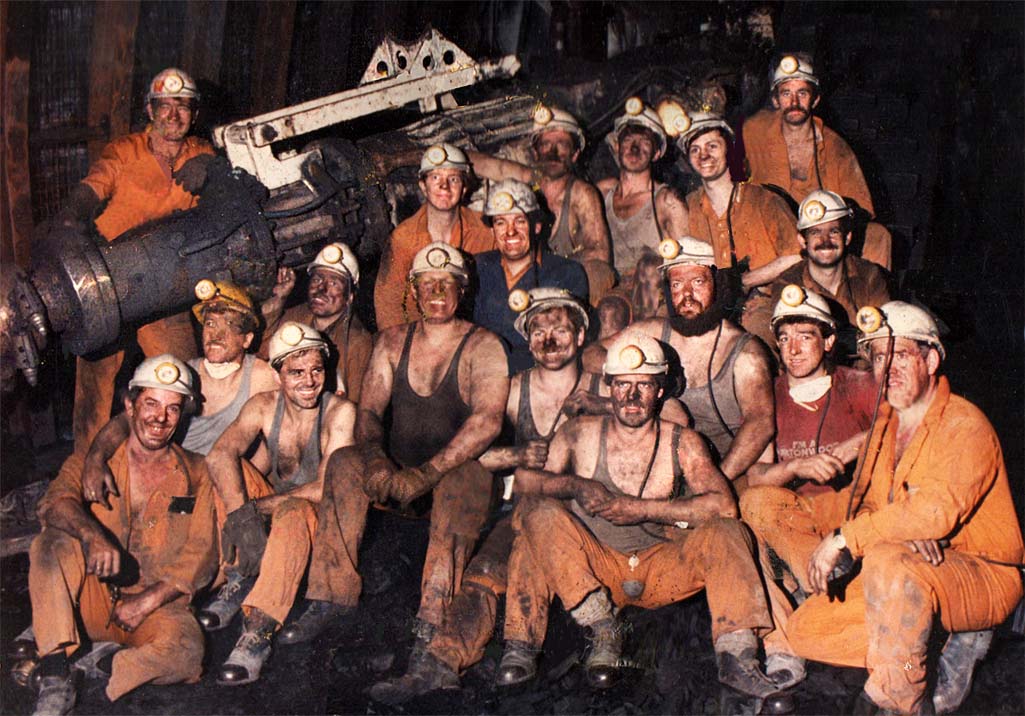

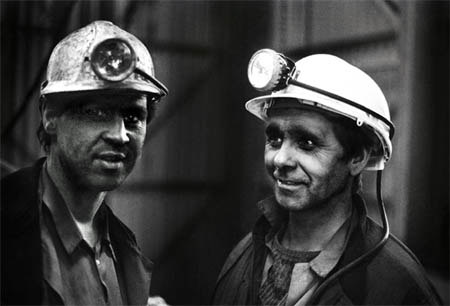

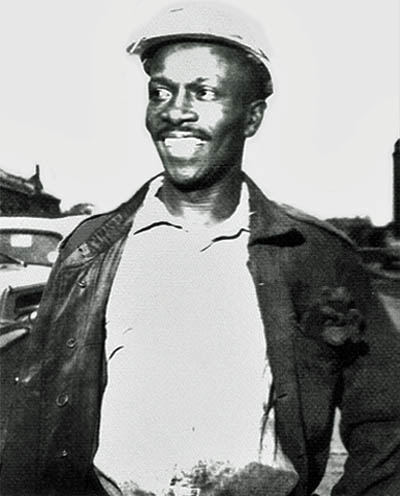

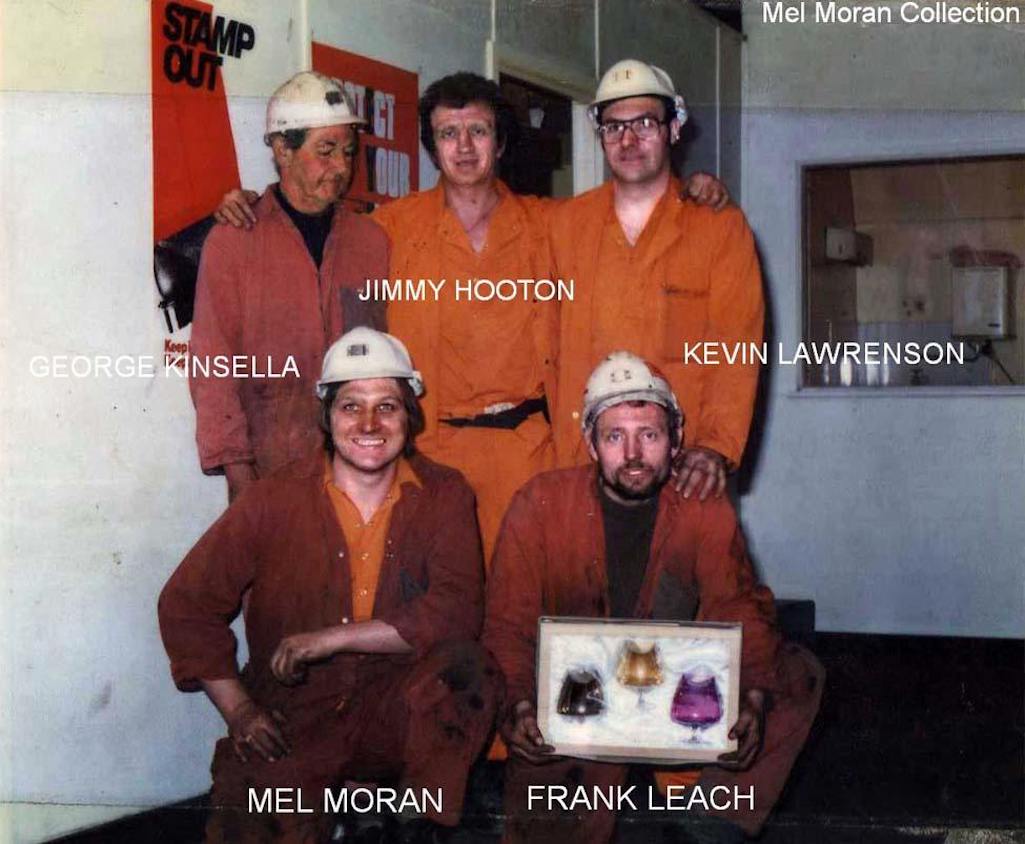

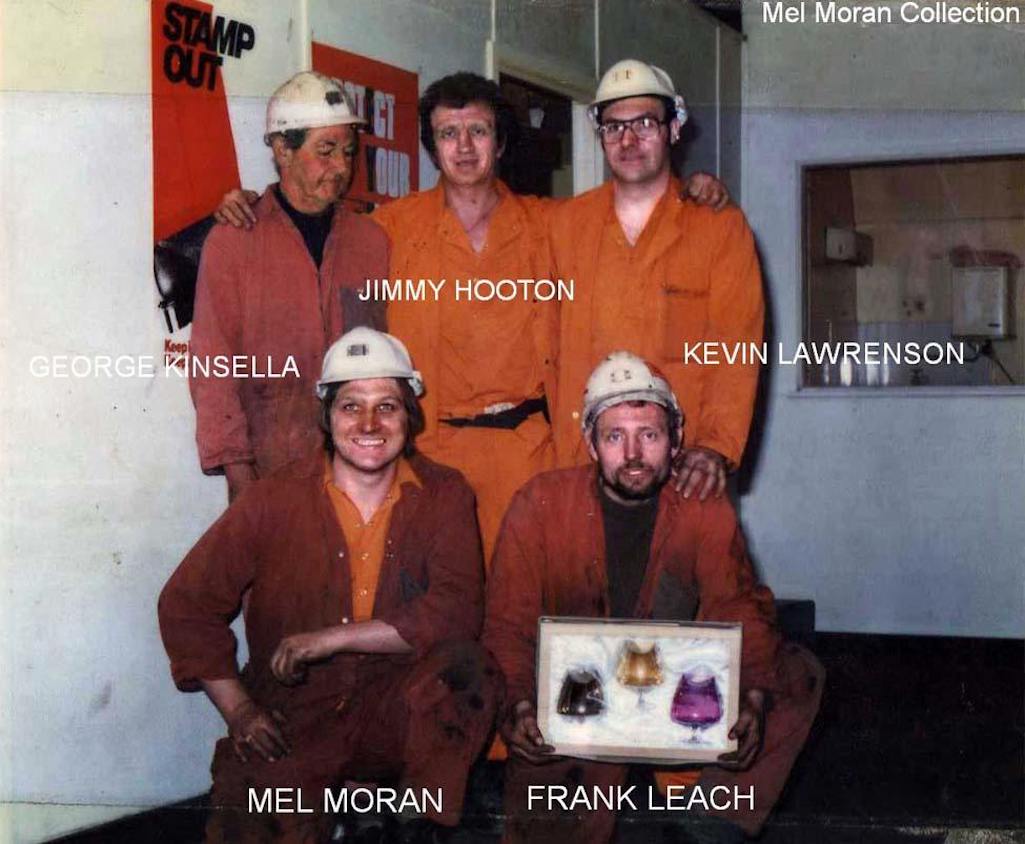

Sutton Manor Colliery mineworkers pictured during the 1980s (Mel Moran Collection)

Sutton Manor Colliery mineworkers pictured during the 1980s

Sutton Manor pitmen during the 1980s