An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 42 (of 95 parts) - Sutton Tragedy Part 2

c) Tragic Demise of Sutton Nash's 'Owd Tolly' | d) Tragic Suicide of Annie Makin

e) Rabid Railway Shunter from Herbert Street | f) The Romantic Sutton Suicide

g) The Drunken Steeplejack | h) Crossing The Line – Rail Deaths in Old Sutton

i) Maternal Murder and Suicide in Old Sutton | j) Child Tragedies in Old Sutton

k) The Sutton National School Storm – A Remarkable Story of Tragedy and Heroism

l) Accidental Drownings in Old Sutton Appendix: Coroners Inquests in Old Sutton

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me Research Sources

The Legendary Curse of St. Anne's Well

Tragic Demise of Sutton Nash's 'Owd Tolly'

The Tragic Suicide of Annie Makin

Rabid Railway Shunter from Herbert Street

Romantic Sutton Suicide | Drunken Steeplejack

Crossing The Line – Rail Deaths in Old Sutton

Maternal Murder and Suicide in Old Sutton

Child Tragedies in Old Sutton, St Helens

The Sutton National School Storm

Accidental Drownings in Old Sutton

Appendix: Coroners Inquests in Old Sutton

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Old Sutton in St Helens

Curse of St. Anne's Well

Tragic Demise of 'Owd Tolly'

Tragic Suicide of Annie Makin

Rabid Railway Shunter

The Romantic Sutton Suicide

The Drunken Steeplejack

Crossing The Line

Maternal Murder & Suicide

Child Tragedies in Sutton

Sutton National School Storm

Accidental Drowning in Sutton

Appendix: Coroners Inquests

The 'Strange Confession' of the Distraught Mum

As Sutton's industrial works built up during the nineteenth century, so substantial water supplies were required for cooling and other uses. So a number of reservoirs were created, mainly in the St Helens Junction district. As described in this story, they created opportunities for play when they were covered in ice that could lead to tragedy. However, the reservoirs didn't have to be frozen to be death traps.On the evening of May 17th 1900, 49-year-old Sarah Walton of 15, Sutton Moss, was walking her two youngest children across the fields by the unfenced reservoir that supplied the Sutton Rolling Mill, when seven-year-old Lily fell in. The screaming mother jumped into the water to try and save her daughter and was followed by three-year-old Agnes May. Passers-by, Edward Williams and Archibald Thompson, heard her cries and pulled all three out of the water. Dr. Bates was summoned from his Junction Lane practice but could only pronounce both children dead.

Mother of ten Sarah was physically unhurt but endured severe shock. Inquests, in those days were held as quickly as possible after death, usually within 48 hours. However, the collier's wife was in no fit state to give evidence and so the hearing was postponed until May 30th. When the delayed inquest took place in the Locomotive Inn at the corner of Ellamsbridge Road and Peckers Hill Road, Sarah was present but was clearly far from well. The Liverpool Mercury of May 31st 1900 described her as in a 'dazed and poor condition' and when it was her turn to give evidence she dropped a bombshell declaring: "It is no use me saying anything. I have done the deed."

Coroner Brighouse asked her what she meant but she simply repeated that she had "done it" . Sarah Walton then asked to speak to the Coroner and Dr. Bates privately and then made a further statement of guilt. Back in the inquiry room, a concerned Sam Brighouse said that considering her condition, it would be unfair to proceed with the inquest and so the Coroner adjourned it. He concluded by advising John Walton, husband of Sarah, to get a solicitor for his wife. The Liverpool Mercury commented: 'The strange confession of Mrs. Walton quickly leaked out in the neighbourhood, and occasioned a sensation.'

Marty Strutt illustrates the scene with little Lily crying for help, Mum attempting a rescue while Agnes wanders closer to danger

Marty Strutt illustrates the tragic scene at the Rolling Mill reservoir in Sutton

Marty Strutt illustrates the tragic scene

Sutton's Sergeant Jackson then gave evidence that he believed Sarah was suffering "very great mental distress" when she'd made her self-incriminating statement of drowning her daughters and so the jury decided to return an open verdict. This saga was brought to an end on June 15th when the case against Sarah Walton was discharged at St.Helens Police Court. Town clerk G. W. Bailey had forwarded all depositions in the case to the Solicitor to the Treasurer who felt that she was under a hallucination when she confessed to drowning her girls. The devoted mother had spent 16 days in custody, mainly in prison, but finally justice was done although her ordeal was not quite over.

Although returned to her family by the courts, Sarah is thought to have spent a long time in Rainhill Asylum, recovering from the mental trauma, before eventually returning home. If you can furnish further details of exactly what happened to Sarah after 1900, please do contact me. Just maybe there's a happy story waiting to be told!

The Legendary Curse of St. Annes Well

When we talk of St. Anne's in Sutton, we automatically think of the Roman Catholic church that John Smith built in 1849 for Dominic Barberi, which now also bears the name of the beatified Passionist priest. However hundreds of years earlier there was another St. Annes located to the west or south-west of what we now call Sherdley Park and which suffered from Henry VIII's draconian Dissolution of the Monasteries. However, the manner of the appropriation has long been the subject of conjecture as to whether there was both a conspiracy and a curse. We'll never know the truth but according to reports, there were certainly a number of tragedies.St. Annes or Sutton Priory was quite small with never more than a dozen priests but with an extensive estate leased to well-off farmers. This brought in a good revenue for the monks who worked a small farm nearby with much of their produce given to the Sutton poor. They also had a well in a field located nearly a mile from the Sutton Priory and half-a-mile from present-day Rainhill station. It was six feet deep and five feet nine inches square and was said to have remarkable healing and curative powers. Large numbers of people travelled from great distances to bathe in the well and a small three roomed house was built over it. Two of the monks lived there to give assistance to those seeking relief from their afflictions. The cure of skin and eye diseases was a speciality of the well, which like the priory, had St. Anne as its patron saint. Indeed the monks claimed that their patroness had one day manifested herself there and bathed in the waters of the well.

By the 1530s the prior was Father Delwaney who fell into dispute with Hugh Darcy, the steward or estate manager of Sir Thomas Bold, the neighbouring landowner. They disagreed over access rights to the well and the boundary between the two estates. The dispute came to a head one day with a row that ended with Darcy suggesting that the prior would not be in position for much longer. This puzzled Fr. Delwaney but it was the reign of King Henry VIII who, at the suggestion of Thomas Cromwell, was busy dissolving monasteries.

A couple of days after Darcy's prediction, two of the king's commissioners, Dr. Layton and Dr. Lea, accompanied by several officers rode up to the priory to take possession. They presented to the prior the orders of Cromwell, the Vicar General, that they were to be removed from Sutton and taken to an abbey at Parr, with each monk allowed just one gown and £2. Fr. Delwaney was also instructed to take the officers to the well so that they could take possession of that as well.

St.Helens Leader article on St.Anne's Well which was part of a series on local traditions and legends c.1877

St.Helens Leader article on St.Anne's Well which was published about 1877

St.Helens Leader article c.1877

The king subsequently granted Hugh Darcy the farm on which the well stood and he demolished the building over it. For a while everything seemed to be going well for him but within three months of Delwaney's death, the steward's only son died of a mysterious illness. Soon afterwards, the bereaved father suffered financial losses through poor investments and he subsequently took to drink, which cost him his job with Thomas Bold. One night after a heavy drinking session at a tavern near Micklehead, Darcy walked back to his home in Rainhill. However, he never arrived and in the morning his concerned wife woke their neighbours who searched for him. The shortest road home was a footpath by St. Anne's Well and Hugh Darcy's body was found in the waters with his head crushed in.

So the curse of the prior had come true and the former warden had received his just deserts. Alternatively, Fr. Delwaney may have had a heart attack and Darcy's son may have died from a childhood disease, that afflicted so many youngsters in those days. Plus the highly intoxicated Darcy may have fallen into the well, caving in his head in the process. Coincidences and simple explanations are not, of course, as romantic a chain of events as the retribution of a deceased monk. It all depends on how much you believe in myths and legends! Incidentally the well has a connection with the derivation of Elephant Lane in Thatto Heath. The then track originally ran to the well and so became known as Holy Font Lane, which was later corrupted to Elephant Lane.

St. Anne’s has long been hidden but in October 2016 experts from Oxford Archaeology North conducted an excavation and uncovered a 2 x 2 metre well, with three steps leading down to a pool of water. Funding has been provided by Historic England to replace stones that had fallen into the well.

The Tragic Demise of Sutton Nash's 'Owd Tolly'

When Arthur Helsby was laid to rest in Sutton Churchyard on July 10th 1930, a huge crowd of over 2,000 mourners sang 'Abide With Me' led by Rev. W. E. Colegrove. The Vicar of Sutton eulogised over the man who'd been a music teacher at Sutton National Schools for almost three decades and had also been the choirmaster and organist at All Saints Church in Ellamsbridge Road for many years:In his memoirs written in 1987, Frank related how he and his classmates were fearful when told that they were moving up into Standard VII, Mr. Helsby's class. The teacher had quite a fearsome reputation for using the strap on his pupils if they couldn't answer his questions. Soon Frank's fears were realised:

Joan Heyes (née Williams), who now lives in Sydney, used to visit All Saints after school to listen to the organ being played. She lived with the Withington family, to whom she was related, initially in Ellen Street and later in Mill Lane. Emily Withington received private organ lessons from Mr. Helsby on Thursday afternoons. Joan recalls regularly climbing the church steps and standing at the side of the long bench that Emily sat on. Tutor Arthur Helsby stood at the other end of the bench but never acknowledged Joan's presence in any way.

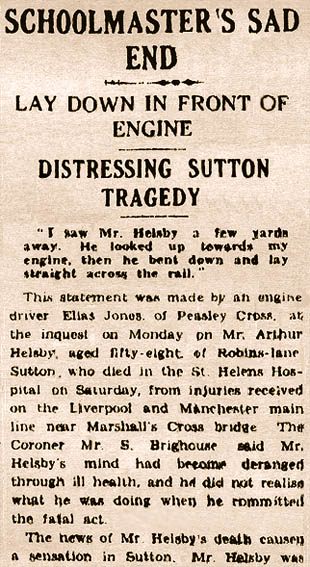

Depite his unpopularity with some, 'Owd Tolly' was so well-known and had participated in so many aspects of Sutton life that it came as a huge shock to the local community when word spread of his death. The St.Helelens Reporter said the news of his suicide had caused 'a sensation'. Fifty-eight-years-old Helsby had walked from his Robins Lane home to Marshalls Cross Road bridge, then made his way down to the railway line before lying down on the tracks in front of an oncoming engine. Coroner Sam Brighouse said Helsby's mind had become "deranged through ill-health" as his son described to the inquest how his father had met with a cycling accident some thirty years earlier in which he'd received serious head injuries. Arthur Francis Helby, a fitter, said that as a result his Dad endured severe headaches and he'd only recently returned to the school after a period off work.

On his final day after a restless night, Arthur Helsby Snr. informed his wife Louisa that he "felt poorly and complained of his head being bad". During the day he sat about the house and watched his son repairing his motor vehicle. The family thought that he'd then gone to his room for a rest but at 6pm they received word that Arthur had been struck by a goods train travelling towards St.Helens Junction from Lea Green. Coroner Brighouse added that Helsby was not in a fit state of mind to appreciate that his actions were "wrong in the sight of God and against the law of the land".

The final word on 'Owd Tolly' has to come from Frank Bamber who concludes his chapter on his Sutton Nash schooldays by summing up his thoughts on his former teacher:

The Tragic Suicide of Annie Makin

The death of many young women as a result of childbirth and disease, created a dilemma for many nineteenth century fathers. Who would cook and keep house for them and look after their children? Remarriage was the solution for quite a number and some took another wife with almost indecent haste. Hiring domestic servants was another option for widowers, although it was cheaper to get other female family members to do the work. When Rachel Makin died in 1881, her husband James hired Elizabeth Burrows to be his housekeeper. The family then lived in Hammond Street, Parr and Makin had six children to bring up. He was only a labourer and despite 'domestics' being poorly paid, he would have struggled to pay Elizabeth as well as provide for his three sons and three daughters.It seems that after moving to 50 Sutton Street in Peasley Cross, which was then part of Sutton, Makin's eldest daughter Sarah was given the task of running his home. Upon her marriage, the responsibility fell upon Sarah's young sister Ann. By 1890, she was just 15-years-old and was clearly a deeply unhappy child with a lot on her young shoulders. Annie was expected to cook and keep house for her four siblings, as well as look after her demanding 45-year-old father, who had a violent temper. On several occasions during the previous year, Sutton bobby PC Littler had been called to Makin's home by worried neighbours who were concerned that he was killing the children.

Early in September 1890, Annie accompanied her friend Mary McNamara when she visited Roughdales pottery works with her brother's dinner. When the pair passed the old water-filled pit at Sherdley Delph, Ann shocked Mary by suggesting that they drown themselves in it. Then on Sunday September 14th, Ann told friend Ellen Lynan, whilst they were in Sutton Churchyard, that if her father "beat her or sauced her again", she would kill herself.

Four days later, Ann was given a severe scolding by her father for letting two friends into the house and giving them currant cakes. So after taking her young brother and sister to school, she went to the Delph where she was seen standing by the water's edge. Witness Joseph Gerrard said she "seemed somewhat strange". Her father took over two days to report his 15-year-old housekeeper daughter missing and was drunk when he went to the police. By then Ann's hat had been found floating in the waters of the Delph, which was some 30 to 40 feet deep. Ann had tightly pinned her dress to reduce the buoyancy effect and it took several more days before her body could be recovered.

At Ann's inquest held on October 2nd, 1890 at the Griffin Inn, coroner Sam Brighouse was highly critical of Makin's treatment of his daughter. The chemical labourer attempted to defend his behaviour, claiming that he hadn't beaten Ann for "three or four months since". In censuring Makin, the coroner commented that he had other children to bring up and hoped that he would "do better to them than he had to the deceased."

The Rabid Railway Shunter from Herbert Street

One of the most feared conditions of the nineteenth century was rabies. Otherwise known as hydrophobia, distressed rabid or 'mad' dogs often bit those that they came into contact with and passed on the deadly disease. However, rabid dogs didn't always foam at the mouth and boisterous canines were often mistaken for afflicted ones. So panic soon became as big a threat as the contagion itself.

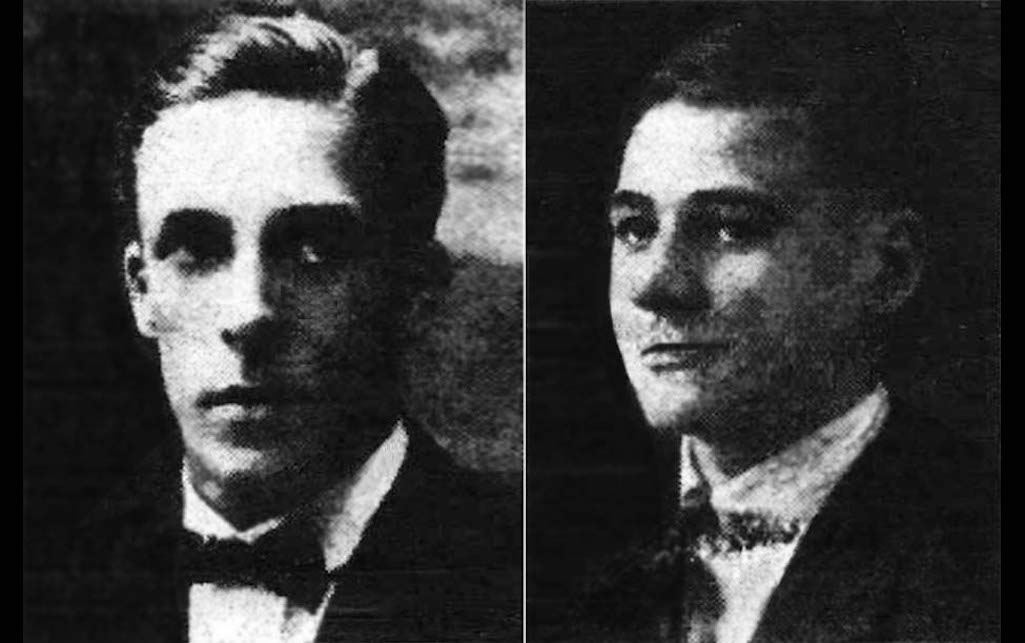

Left: 1824 Liverpool Mercury headline; Middle: Liverpool Mercury September 13th 1892; Right: James Lucas and James Wood

Liverpool Mercury from 1824 and 1892; Right: James Lucas and James Wood

Two Liverpool Mercury articles, James Lucas & Chief Constable James Wood

Irish railwayman John Campbell of 118 Herbert Street developed rabies after being seconded to work in Preston. On June 23rd 1892, while in charge of a level crossing, the 41-years-old shunter saw a collie dog on the line. Concerned that the animal would be run over, he called it over to him. The St.Helens Reporter described how the dog came quietly but on reaching him:

At John Campbell's funeral on the following Sunday, thousands of Sutton folk lined the streets to pay their respects. Roughdale's Brass Band led the procession to St. Annes church and over 200 railway employees participated. Instead of a hearse, the coffin was carried by relays of railwaymen. Campbell left a widow Ellen and six young children and the St Helens Reporter described how the funeral affected his family: '…the procession slowly filed down the church. The widow completely broke down and had to be assisted along the aisle, followed by the little crying children.'

John Campbell had arrived in Sutton about 1881 and the Reporter said he had been a 'finely built fellow', having served in the army. In fact he'd relived his army life in his delusions just before he died. Campbell was considered a hero for saving the life of a dog. His kindly act had led to his own death and there was much sympathy for his family's plight. So in September a fund was opened to support the Campbells managed by St Helens Junction stationmaster, James Lucas.

The rabies plague reached its peak in Lancashire during the 1890s. On November 12th 1892, the Chief Constable of St Helens, James Wood, issued his annual report. He revealed that proceedings had been taken against 100 people for breaching the controversial Rabies (MuzzIng of Dogs) Order. Wood's police force had obtained convictions against 97 people and 138 dogs had been seized of which 74 were destroyed. This was not because they had rabies, it was simply that the dogs were on the streets unmuzzled.

Dog lovers were enraged by the order being implemented in St Helens, despite there having been 26 cases of rabies in Lancashire during 1893. At a St Helens Town Council meeting on October 3rd 1894, Councillor Mearns said it was a "pitiable sight" to see big policemen "running about the streets chasing little animals about the size of kittens". The muzzling order ended within a few years, although it wasn't until 1922 that rabies was eradicated from Britain.

As regards Ellen Campbell, she endured a second tragedy after marrying James Garner, who was also a railway shunter like her first husband. They lived at 148 Mill Lane in Sutton and had three children, Joseph, Ellen and Claude. Garner worked for the L and NW railway for 27 years, until he was killed in a wagon accident at Ravenhead on May 12th 1902. James and Ellen's daughter Ellen, incidentally, married James Emblem Johnson, who is featured in Sutton at War Part 2.

The Romantic Suicide

The death of a spouse after many years of marriage can, of course, be very hard to bear. Today there is bereavement counselling and social services that can help. However, in old Sutton there was nothing. When Margaret Birch of 76 Baxters Lane died in June 1891, her husband John was distraught. They'd been married for around forty years and the 62-years-old soon became depressed over his loss. It probably didn't help that he'd retired early from his job as a sawyer, and so had little to occupy his mind. He'd been employed in sawing timber for many years and perhaps an industrial accident had caused his retirement. In those days someone of John's age was considered quite old. However, with little pension provision, they would usually work for as long as physically able.John Birch had two daughters and a son and he told them that he would die within two yards of their mother's grave. Margaret was buried in Sutton Churchyard, although it's not known whether his prediction was perceived as a suicide threat. However, on the morning of Tuesday April 25th 1893, all doubt was removed when Birch wrote the word 'Poison' on a bottle of liniment and went to the churchyard. The widower drank from the bottle and then lay down on his beloved wife's grave.

The sexton at St. Nicholas Church, Mr. Lester, found Birch sprawled unconscious and immediately summoned Dr. Baker Bates from his Junction Road surgery. Sutton's popular medic conveyed Birch to the Cottage Hospital, but within hours he was dead. The Manchester Times headlined their report 'Romantic Suicide at St. Helens', and described how the usual verdict of 'suicide while of unsound mind' had been returned at Birch's inquest.

St.Nicholas Church photographed from New Street around 1910 with part of the old graveyard

St.Nicholas Church pictured around 1910 with part of the old graveyard

The old graveyard at St.Nicholas

John Birch's burial took place the day after his inquest and it is listed in the Sutton parish records (no. 556). However, just what happened to his remains is not known or, indeed, that of his wife's. Grave location numbers were not allotted until 1906, but a careful search of the old graveyard has revealed no trace of Margaret's grave. Could the children have had their mother's remains removed from its grave and interred with their father in unconsecrated ground, so they could lay together? Perhaps there was a romantic ending to the romantic suicide?

The Drunken Steeplejack

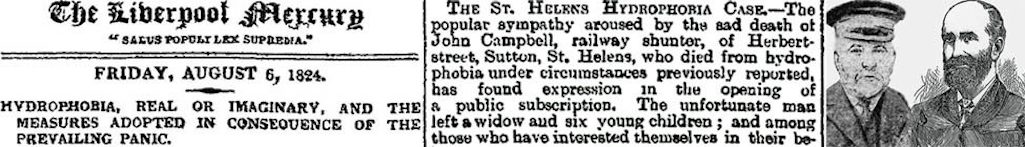

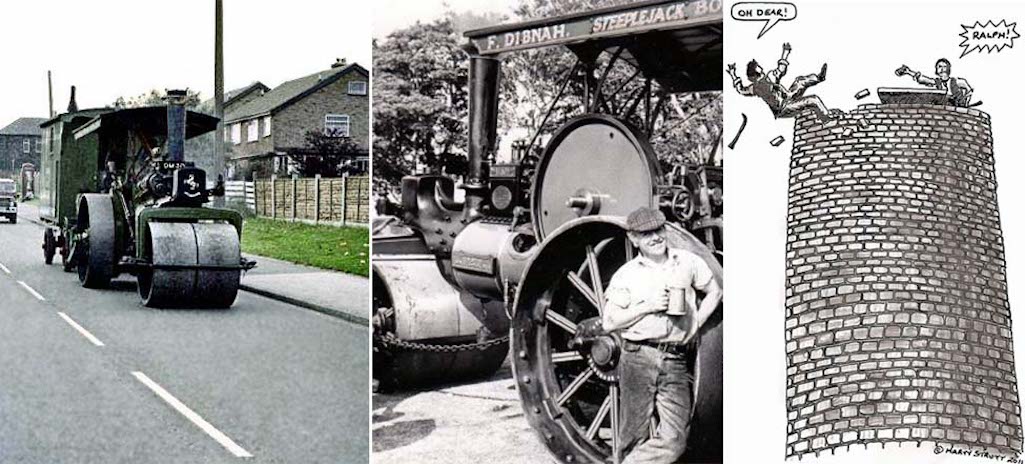

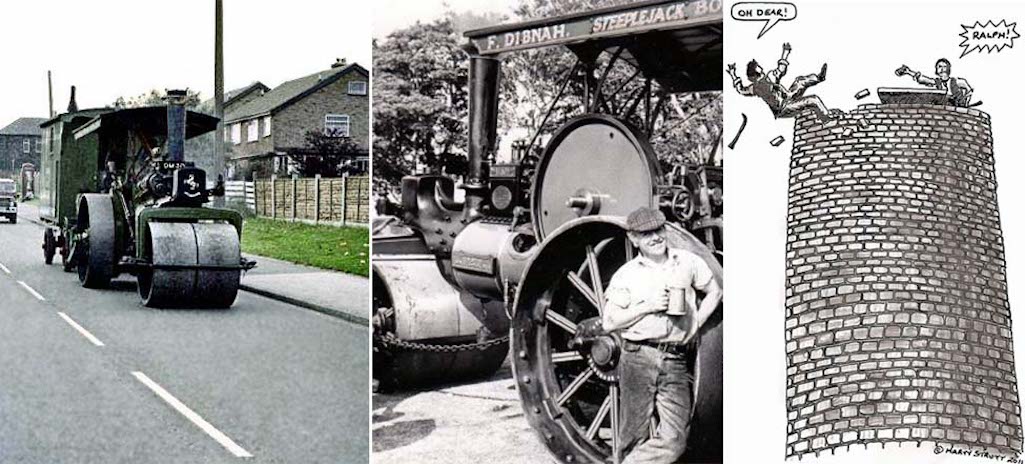

The risky work of steeplejacks was brought home to television viewers by Fred Dibnah in his BBC series of the '70s and '80s. I'm unaware of Fred undertaking any work in Sutton, but he certainly came here when appearing at the St.Helens Show in Sherdley Park. His trademark steamroller is pictured below in Mill Lane in 1996, taken by Jim Lamb. During Fred's time, there weren't that many chimneys and steeples in the district that needed repair or demolition. In old Sutton there were far more and working on them would sometimes lead to tragedy. Herbert Eden tells me that around 1930, the old steeple at St.Annes church had seen off a steeplejack and a stone in the graveyard commemorated the death.Although an eccentric, Fred Dibnah was a careful climber and not a risk-taker, aware that he'd only fall off a chimney once! He certainly liked his pint but didn't do any climbing after having a skin full. This was in stark contrast to Ralph Woods who in 1892, fell 183 feet to his death from a chimney at Sutton Copper Works. The 27-years-old had only been working for S. P. Bidder's chimney builders and repairers of Manchester for nine months. However, he'd already developed a reputation for recklessness and liking his beer too much.

At Wood's inquest at the Manor Arms in Sutton Road, his co-worker John Mains described their boozing on the day of the accident. He said they'd left Warrington on the 10 o'clock train on August 8th 1892, but had got off at Earlestown, where they went to the Railway Hotel. Mains said they stayed there until 2pm, but claimed they'd only drunk two pints each. This seems rather unlikely over a period of 3½ hours. He also said they drank a pint while walking to Sutton and another during a break from the chimney work.

a) Fred Dibnah in Mill Lane contributed by Jim Lamb; b) In Sherdley Park; c) Marty Strutt illustrates the drunken steeplejack

Fred Dibnah in Mill Lane and Sherdley Park and drunken steeplejack illustration

Fred Dibnah in Sutton and an illustration of the drunken steeplejack

The duo's approach to health and safety was minimal and there was no scaffolding. Instead the two steeplejacks stood on boards at the top of chimney, which had a diameter of 11 feet. It had only been built in 1882 to a height of 183 feet but had suffered during recent storms, shedding a number of bricks and stones. Woods and Mains used small crowbars to 'prize off' the brickwork. They worked on opposite sides of the chimney and the brickwork and coping gave them a standing width of just two feet. They threw broken bricks and stones down to the ground and a crowd of hundreds gathered to watch them.

About 7.30pm, Woods pushed over some stones and bricks and was seen to stagger. The horrified onlookers then saw him fall headlong to the ground, his skull striking the edge of a brick, crushing it into the earth. Dr. Bates was called to the scene and found every bone in Wood's body smashed to pieces. Word soon got round Sutton, and the crowd of people multiplied into thousands.

The deceased's boss accepted no responsibility for the accident and was instead critical of his own employee. S. P. Bidder said Woods was a "reckless and careless man", and added that he would unnecessarily walk round the chimney top, exposing himself to danger. The coroner felt that drink was the real culprit saying "They don't fence round the chimney, and they don't fence the public house." This wasn't the first fatal fall at Sutton Copper Works. Less than a year earlier, 12-years-old William Dean had fallen from a scaffold within the plant after being told to retrieve a mallet. By the time that the steeplejack fell to his death, Sutton Copper Works, owned by Newton, Keates and Co. and located near Worsley Brow, was gradually laying off staff. It smelted its last ore in December 1895 after over 60 years of production.

Crossing The Line – Rail Deaths in Old Sutton

My grandfather, Edward Wainwright, was killed by a train at Rainford in 1962. The exact circumstances will never be known as he was said to be depressed as well as deaf, offering two possible reasons for the tragedy. One would have thought that it would be quite difficult to not see a big, noisy steam loco coming at you. However, the more I've researched Sutton, the more examples I've found of people who'd been accidentally mowed down by trains.Much of the old railway network in Rainford is now a pleasant linear park. However in old Sutton, railway lines made for handy linear paths that created shortcuts. With no cars and buses, most people walked to and from work. Using the railway lines could save a few minutes, although it cost a number their lives. Tough miners, who faced death daily down the pit, were prime offenders who thought nothing of walking and crossing the lines.

In 1895, George Clarke, an 18-years-old collier from Pye Street, was killed by an express passenger train while taking a 'near cut' to Bold Colliery. Clarke's inquest was held, rather appropriately, at the Railway Hotel at St. Helens Junction on July 2nd. His mate James Butler told the inquiry that they'd climbed over the railway fence so they could walk to work along the line. Engine driver George Shaw stated that he blew his whistle for a quarter of a mile and a juror who heard it remarked that the whistle was loud and prolonged. However, Butler claimed that they didn't hear a thing. Coroner Brighouse said: "I don't like to say anything harsh, but if people will do these things they must run the risk."

Sometimes, like my grandfather, it was a question of crossing the lines as opposed to walking along them. Even though a footbridge had been provided for Bold miners to safely cross the railway track, some preferred to walk directly across. This cost 16-years-old Walter Houghton his life on July 11th 1899 after leaving the colliery to walk home to Parr. He was run down by an express passenger train from Liverpool and was said to have received shocking injuries.

This was despite a safety campaign in which detectives had brought actions against colliers who they'd seen on the lines. On August 20th 1894, twelve miners - Patrick Gaffney, Patrick Powell, Harry Taylor, William Routledge, Harry Travis, James Hayes, Thomas Highcock, John Tynan, William Houghton, John Murphy, Anthony Smith and James Owen – were each fined 5 shillings for trespassing on the lines of the London and North Western Railway Company. They were spotted at Lea Green and at St. Helens Junction and it was remarked in court that despite a number of deaths, people were still risking their lives.

A year earlier, on April 19th 1893, Bold Colliery miner Joseph Newton had successfully brought an action for false imprisonment against the L & NW company. He was walking along the line at Sutton Moss with other colliers after leaving work when Detective White of the railway company seized him. Newton alleged that White had dragged him through a broken fence, handcuffed him, then put him into the van of a goods train that the detective had stopped. The miner was taken to Sutton Oak, then transferred to Widnes where he was locked up for the night. The jury at St.Helens County Court awarded Joseph Newton £5 damages for the detective's over-zealous actions.

The railway track could also be used by thieves to make their getaway. On July 6th 1856, James Wilson used the line at Sutton Moss to return home after stealing 14 cabbages. He was earning good money as a blacksmith but decided to help himself to produce from the garden of John Slater in the dead of night. He was struck down by the mail train at 2:30am and discovered by John Ferguson about an hour later. Today, one would contact the emergency services and not be expected to touch the body. However, it was quite different in Ferguson's time with no telephone, hospital or ambulance service and with only a small, limited police force. So when accidents happened, people often took the dead to the nearest pub, as that was where their inquest would be held. Ferguson picked up Wilson's lifeless body and took it to the Wheatsheaf, which was then in Lionel Street. His inquest was held there the next day and the condition of his remains was described as a 'sickening spectacle'. Wilson left a wife and five children.

On November 5th 1896, the Gamble Institute was officially opened in St.Helens and the 2nd Volunteer Battalion of the South Lancashire Regiment paraded as part of the ceremony. Patrick Ryan of 17, Sutton Moss was a member of the battalion and when the event ended, he enjoyed a few drinks in a town centre pub and then walked home. While walking on the railway line near to Sutton Oak station, the Irishman was struck by an engine that was proceeding to the nearby sheds. The 43-years-old furnaceman at Sutton Copper Works was instantly killed. Both of his legs were smashed and his body was badly mutilated. Patrick Ryan left a widow Mary and three young children.

People who lived near railway stations were also prone to walking the lines to save them time before taking a train or after departing one. On October 7th 1871, Samuel Lucas was walking home from Sutton Oak station when he was run over and killed by a train. One of his feet was cut off and his face was said to have been completely smashed. Even railway workers who were fully aware of the dangers walked the line to and from work. On September 18th 1892 a signalman called Harrison who lived in Sutton Leach was knocked down by an engine while walking along the line to his signal box at Clock Face. An arm was severed from his body and his skull was fractured.

The deadly lines at Sutton Oak station - it was easier to walk across the track than use a footbridge

Deadly lines at Sutton Oak station - many chose to walk across the track

The deadly lines at Sutton Oak station

Then on the morning of November 16th 1881, Father Sebastian of Sutton Monastery was cut to pieces - literally - after stepping in front of the ten o'clock Liverpool to Manchester express. The Italian was only two yards from the footbridge to the other platform. However, concerned he'd miss his train, he chose instead to dash across the rails to his death. One of the saddest tragedies took place at Sutton Oak station on November 23rd 1889. It was a foggy night and Mrs. Canning, a 23-years-old glassmaker's wife, carried her young child over the 'metals'. She failed to see a goods train approaching and the child was instantly killed and the mother died in the Cottage Hospital in Peasley Cross five days later.

People who trespass on the railway these days are more likely to be committing vandalism, stealing copper cable or taking their own lives, rather than using the lines as a short-cut. With much better roads and transportation, Sutton folk have no need to walk or cross the lines anymore. However nationally as many as fifty individuals lose their lives each year by trespassing on the railway.

Maternal Murder and Suicide in Old Sutton

In the article Tragedy of a Pond in Sutton Tragedy Part 1, Rachel Machin suffering from post-natal depression chose to end her life but not that of her child. However, this was not always the case. With depression rarely treated by medical practitioners, mentally-ill mothers sometimes took the lives of their children as well as their own.On April 23rd 1885, 40-years-old Jane Hamilton threw herself and her four-years-old son Thomas off a Sutton bridge into the waters below. A rag gatherer called Hagan waded into the water, which was only four feet deep. However, he decided to turn back and some time elapsed before two other men jumped in and retrieved their dead bodies. Jane was the wife of James Hamilton, who was a labourer at Sutton Glass Works and the former gardener of glass boss William Blinkhorn. They lived at Highfield Terrace in Sutton and she was reported to have been depressed.

At the inquest held at the Running Horses in St Helens, her husband disputed this and an open verdict was returned. Perhaps James felt it would be shameful to admit any mental illness in the family. Shame was the reason that Louisa Hunt gave for killing herself and her six-months-old child Elizabeth. This occurred in July 1896 after she'd been accused of stealing a pair of boots. Clearly disturbed, Louisa drowned her baby and herself in the Ravenhead Glassworks' reservoir. In her suicide note she denied the theft and said she'd be better off dead than endure disgrace.

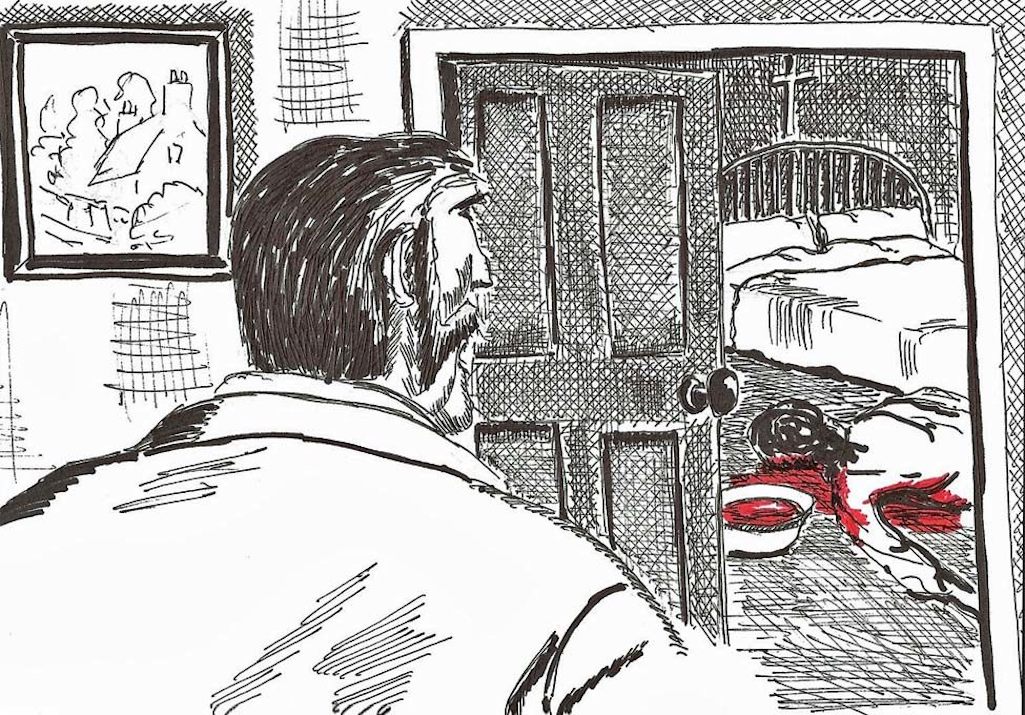

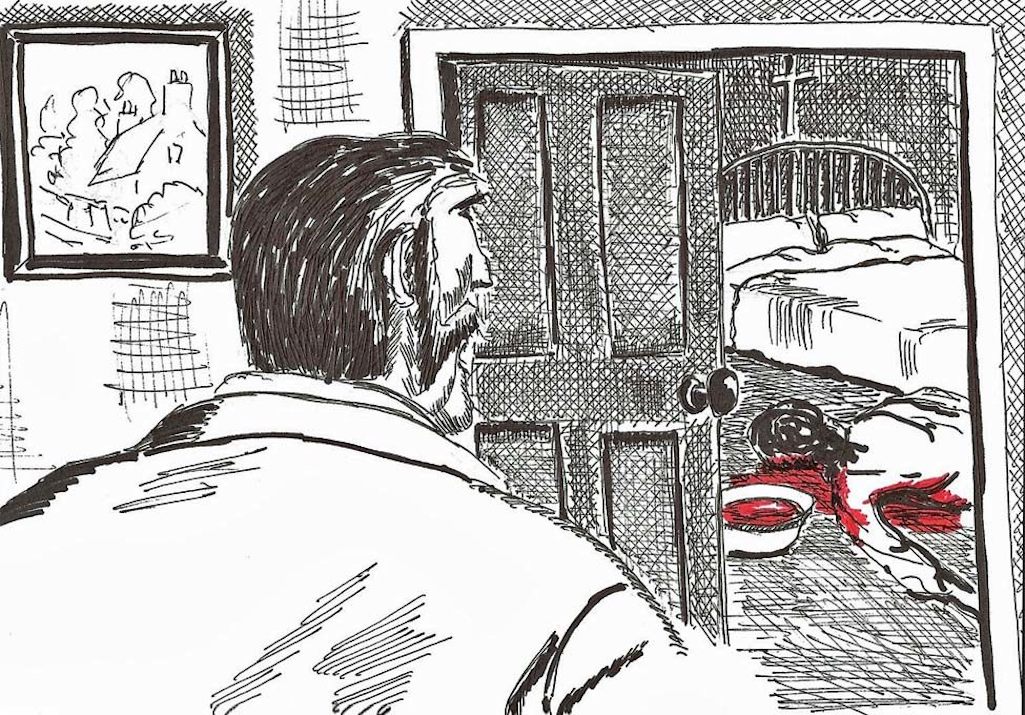

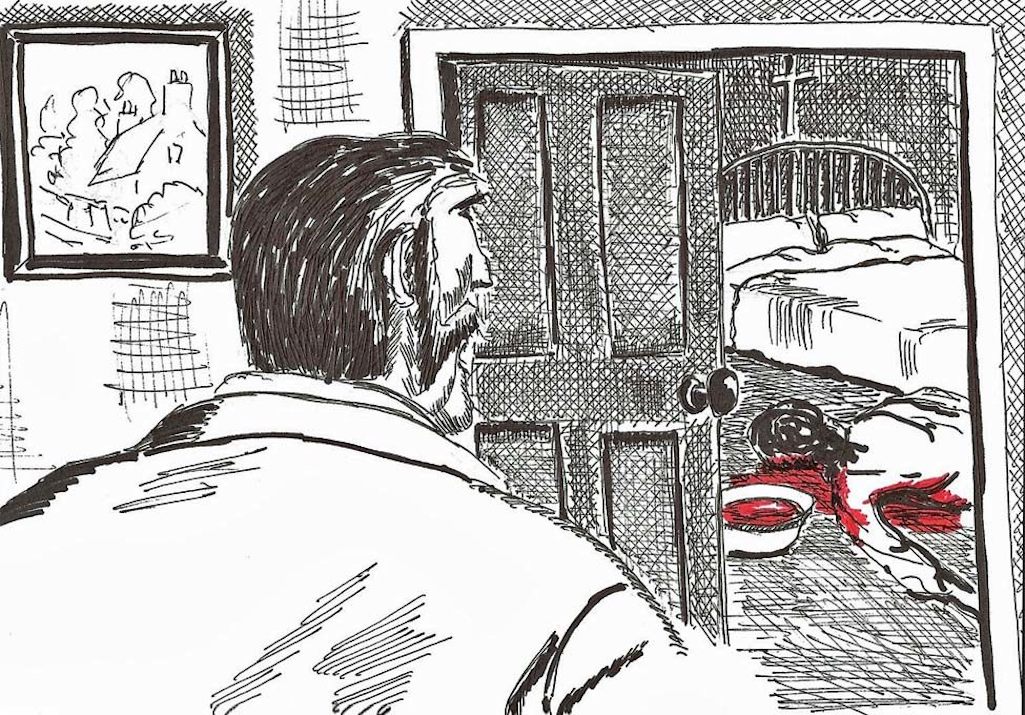

Fourteen years earlier, on March 28th, 1882, 27-years-old Mary Rawlinson of Mill Brow sang with her husband as he got dressed. Alfred Rawlinson was the manager of the Lancashire Chemical Company's Manure Works at Sutton and his wife was the daughter of a Barnsley boiler maker. They'd only moved from Barnsley some months earlier, where Rawlinson had an administrative post at a local colliery. Mary had been depressed as her father and brother were seriously ill, but she now seemed in better spirits. Certainly when Alfred returned from work at ten minutes past six that evening, he could never have imagined the scene of horror awaiting him.

Illustrator Marty Strutt visualises the scene inside the bedroom after breaking the door chain

Marty Strutt visualises the scene after the bedroom door chain is broken

Illustrator Marty Strutt visualises the gory scene inside the bedroom

However, worse was in store for Rawlinson. On looking into a cradle by the side of the bed, he discovered that his son was also dead, killed by his mother. The boy had been named Alfred after his father but was known to the couple by his middle name of Arnold. Touching his son he found him quite cold and a post-mortem revealed that he'd been suffocated around lunchtime. However Mary had only killed herself minutes before her husband's return. When Police Sergeant Richard Banks searched the room he found a suicide note. Mary had hidden it behind a picture and addressed it to her husband. She wrote:

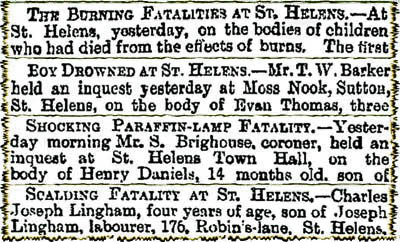

Child Tragedies in Old Sutton

It wasn't easy being a youngster in old Sutton. Child mortality rates were high with low resistance to infections and diseases like typhoid and scarlet fever. Then there were numerous hazards for toddlers to overcome, such as open fires and dolly tubs within the house and ponds, deep brooks and reservoirs outside. Coal fires were ruthless killers with flickering flames and crackling sounds that proved a great attraction to kids. With no central heating, children would sit very close to fires during the winter months in order to get warm. There were countless fatalities as youngsters died a horrible death as their flammable clothing was set alight by sparks, cinders or firewood. Their bereaved parents then had to live with their guilt for leaving their kids alone, albeit often for brief periods of time.On January 18th 1891, the mother of two-years-old Thomas Evans of 4 Powder Works Yard in Sutton was called to a neighbour's house. She was only away for a few minutes but it was long enough for the toddler's nightdress to ignite. The boy was sitting on a stool by the fire when a cinder fell from the grate. A lad named Grice ran into the house and badly burnt his hand trying to extinguish the flames. Young Thomas received severe burns to his body and died three hours later. At his inquest, the lad Grice was complimented for his bravery in attempting to save the boy and a juror handed him a reward.

Death often came very quickly as with five-years-old Archibald McKinnon of Ditch Hillock in Sutton. On December 12th 1865, the boy went downstairs and sat next to the fire to get warm. A piece of firewood fell from the grate and immediately ignited his shirt. The son of glassmaker Duncan McKinnon received severe burns and was soon dead. Even the police endured such domestic tragedies. PC Carter of Peasley Cross kept a fire burning in the kitchen grate during the periods he was on duty. On March 24th 1884 his 4-years-old son William Edward crept down the stairs while his parents were asleep and by some means set his nightdress on fire. The Liverpool Echo said Willie had been 'shockingly burnt' and later died of his injuries.

PC Henry Fillingham's daughter Lilly burned to death on November 27th 1891 after her clothes were set alight when she put coal on the fire. Both her parents were upstairs at the time in their Helsby Street home. After hearing their child's screams, the pair rushed down the stairs so fast that they fell and hurt themselves. Both Henry and his wife Ann needed medical treatment as a result, but it would have been the least of their worries. PC Fillingham was a member of St.John's Ambulance but his first aid skills couldn't save his own daughter. On the following day, three-years-old Samuel Kirkham of 9 Burtonhead Road died after being left alone for a few minutes. The son of a bricklayer was warming his hands on the fire and received severe burns to his body and legs. Dr. Casey attended Samuel but couldn't save him.

A distressing spectacle took place in Marshalls Cross on November 29th 1897 when Elizabeth Smart caught fire. The four-years-old had briefly been left home alone at 7 Chester Lane when somehow her clothes got ablaze. The little girl was the daughter of chemical labourer Joseph Smart and she ran into the street to get help. Although her flames were quickly extinguished, Elizabeth had been severely charred and burned and died two hours later.

Three-years-old Emma Forrest of 22 Clock Face Road was badly burned about the face and arms on November 10th 1899. The little girl had used the fire to light a piece of paper and her clothes were set alight. Dr. Baker Bates attended but couldn't save her life. Paraffin lamps were also a fire risk for inquisitive children. Fourteen-months-old Henry Daniels of 26 Taylor Street in Sutton pulled a lamp off a table while visiting his grandmother's house on September 2nd 1892. Badly burned, the toddler died five days later at Providence Hospital in St.Helens.

A fire began and the child was so badly burned that she was said to resemble a roasted chicken. The jury foreman told the coroner that they considered the conduct of the mother "most inhuman and deserving of all the censure you can give her". However their criticism might have been influenced by Freeman's admission that she'd left her husband, who since 1914 had been fighting in France. In fact for the last fourteen months, she'd been sharing a house at 16 Fenney's Lane, Sutton, with colliery worker Robert Forster. That in itself would have been considered quite scandalous.

In Victorian times the kitchen fireplace was usually the centrepiece of a range that provided cooking facilities and hot water as well as heat. A cast iron kettle was either hung over the fire on a hook and chain or placed on iron plates. These days kettles are less accessible to playful children but not so in the past. In March 1862, four years-old Jane Talbot was scalded to death by a kettle of boiling water. Her inquest was held at the Navigation Tavern where it was stated that the child was playing when she fell against the kettle.

Just over a year later on June 19th 1863, an inquest was held at the Hawk and Buck on Joseph Freeman. The little boy had been playing inside his Peasley Cross Lane home when he fell against a can of hot water. The scalding he received brought on convulsions from which Joseph died. Then on New Year's Day 1892, four-years-old Charles Lingham of 176 Robins Lane received a severe scalding to his body. His mother Rose had placed a pan of boiling water on the floor and the playful child fell into it. Despite the efforts of Dr. Baker Bates, the young boy died two days later. Little Ethel Garner of 81 Clock Face Road had only just recovered from pneumonia when she fell backwards into a pan of boiling water that her mother had carried into the yard. The accident happened to the three-years-old girl on December 27th 1918 and she died from her scalds on the following day.

Accidental drownings of young children were more common in Victorian times than today and could even occur in and around the home. Three-years-old Michael Ratagan of 6 Moss Nook in Sutton died on September 2nd 1892 after playing in his yard. He'd fallen into a dolly-tub and was found face down in ten inches of water. Three-years-old Evan Thomas drowned in a pit of water near to his parents' cottage at Moss Nook on May 16th 1879 while out playing. Then in July 1895, two-years-old painter's daughter Mary Fisher of Leach Farm drowned in a three-feet-deep brook that was just 200 yards from her home. It was said at Mary's inquest that she'd wandered from her house and fallen into the brook.

The saddest case that I've come across occurred in August 1855 when a girl called Ellen Stringfellow found the putrefied remains of a child. It was thought that the unknown child had been with tramps who had simply deserted him or her after death. The body had lain in a Marshalls Cross lane for two to three weeks before young Ellen made the grisly discovery. Deaths of children were so common that just seven lines were devoted to the story by the Liverpool Mercury.

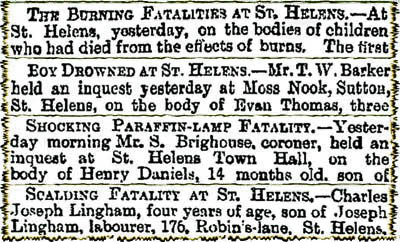

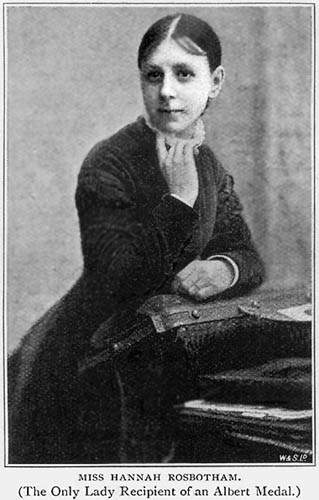

The Sutton National Storm – Tragedy and Heroism

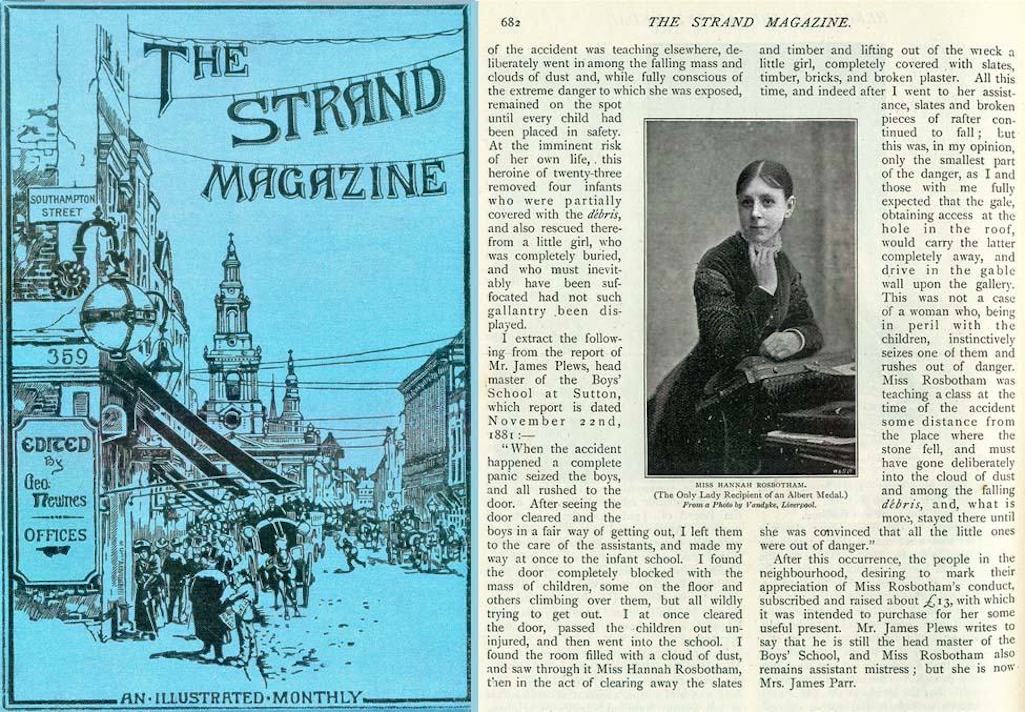

At the National Schools almost two hundred little children were crammed into the infants' schoolroom as the gale reached its climax. The winds struck the school belfry and blew down a stone that weighed almost a ton onto forty infants who were standing on a gallery. Four-years-old Harriet Bradbury was instantly killed and other youngsters were badly injured and covered in debris.

Assistant schoolmistress Hannah Rosbotham was teaching elsewhere as the disaster unfolded but rushed to the scene. While others fled to safety, the 23-years-old bravely entered the schoolroom and rescued five pupils who were covered in debris, as slates, bricks and pieces of rafter rained down. There was also a grave danger of the schoolroom's gable wall caving in on them. One little girl was completely buried in debris and would have soon suffocated if it hadn't been for Hannah's prompt action.

Most of the children escaped unhurt but about eight were badly injured. Newspapers reported that young Ellen Challoner and Josiah Marsh were so severely hurt that their lives were 'despaired of'. However they both seem to have survived and Harriet Bradbury was the only reported loss of life. The little girl had lived at 5 Blinkhorn Row in Sutton, near New Street, with her 60-years-old labourer father Jonathan and mother Mary Ann. Although 56 years of age, Mary had given birth just a year earlier and the couple had a total of nine children still living at home.

The poor people of Sutton thanked teacher Hannah Rosbotham for her bravery by holding a collection that raised the sum of £13 (about £1,500 in today's money). Hannah was the daughter of glass cutter Peter Rosbotham and at the time of the disaster was living at 8 New Street with mother Elizabeth and siblings Mary, John and Frances. The Rev. George Tripp, a curate at St. Nicholas church, was a boarder with the family.

On December 16th of 1881, Queen Victoria conferred the Albert Medal on the heroine from Sutton. Often described as the Victoria Cross for civilians, the award had been instituted in 1866 in memory of Prince Albert for acts of gallantry at sea. It had only been extended to cover the saving of life on land four years prior to Hannah being given her award and she was the first female recipient. In fact by 1896 when Strand Magazine profiled Hannah, she was still the only female award holder. The popular illustrated monthly was renowned for publishing Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories and other notable contributors were H.G. Wells, Agatha Christie, Rudyard Kipling, P.G. Wodehouse and Winston Churchill.

Their article on Hannah included this extract from a report on the Sutton tragedy by Boys' School headmaster James Plews, dated November 22nd 1881:

Part of the Strand magazine's article on heroic Hannah Rosbotham of Sutton which was published in 1896

Strand magazine's article on heroic Hannah Rosbotham published in 1896

Strand magazine's article from 1896

The simple gravestone of Hannah Parr (née Rosbotham) in Sutton Parish Churchyard

The gravestone of Hannah Parr (née Rosbotham) in Sutton Parish Churchyard

The simple gravestone of Hannah Parr

Why there is no mention of the award on her gravestone is a bit of a mystery. There's not even the letters 'AM' inscribed after her name. However Hannah and James don't appear to have had any children, so those responsible for her burial in 1935, fifty-three years after the award, may not have been aware of it. Hannah's medal has survived and is in a private collection in the United States. What a shame there is nothing in St Helens to commemorate her brave act.

Accidental Drownings in Old Sutton

Every year 400 people in the UK die from drowning, although in the past this figure, with a much smaller population, was far higher. The many works’ reservoirs, ponds and clay pits were a magnet for the adventurous and suicidal. These tragedy pages have so far examined cases of children drowning while skating on frozen reservoirs, a Home Guard drowning on a training exercise, suicide in ponds and lakes, plus accidental deaths of children who’d fallen into water. This article will concentrate on the deaths of individuals who lost their lives while swimming in Sutton.In August 1911 the Mayor of St.Helens, Sir Joseph Beecham, said at a council meeting that at present they saw boys bathing "wherever they could get into water". This was in a discussion stimulated by Cllr. Abbott who was calling for the conversion into open-air baths of three Sutton sandpits. Alderman Dixon-Nuttall – a former councillor for West Sutton and President of St.Helens Swimming Club – said that would be "most objectionable, most dangerous, and most undesirable".

Youngsters swimming in an old clay hole near to St Helens Hospital in Peasley Cross - contributed by Ian Bate

Youngsters swimming in an old clay hole near to St Helens Hospital

Youngsters swimming in an old clay hole near to St Helens Hospital

P.C. Alexander Trail had only recently returned to work after a serious illness but ran half a mile to get to the scene. He was only a fair swimmer but immediately dived into the reservoir, which was 11 feet deep with a foot of mud at the bottom. The constable, who had five children of his own, used a pole to try and locate the boy and only stopped after becoming exhausted. On August 24th Trail and two other men who'd assisted in the failed attempt (including Joseph Jump of 3 Rolling Mill Lane) were commended and given framed certificates and a 15 shillings reward.

Swimming in Sutton’s waterways was, however, a practice not reserved just for boys. On Sunday September 29th 1895, 27-year-old collier John Kerfoot of 21 Sutton Heath Road was drowned in Sutton Lodge dam after consuming four pints of beer. Initially they had swum in St.Helens Canal, which was a popular venue for outdoor swimming, before transferring to the Lodge dam. He decided to race his pal John Molyneux across the water for half a gallon of beer. But after half the distance had been covered, Kerfoot was seized with cramp and immediately sank in the water. He was drowned before his body could be recovered.

In another incident on one warm late Spring day in 1932, a group of mineworkers decided to go for a swim in the Lea Green Colliery reservoir. This was despite the fact that it was considered such a dangerous place to swim, that it had been banned by the colliery’s management. That fact hadn’t deterred a number of schoolchildren, who were also enjoying themselves in the water.

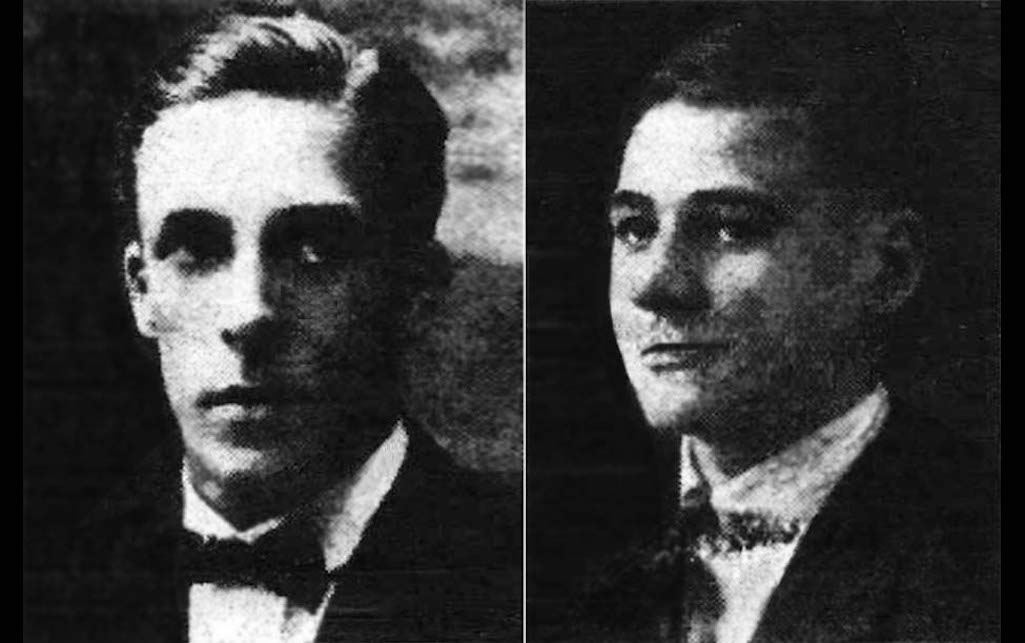

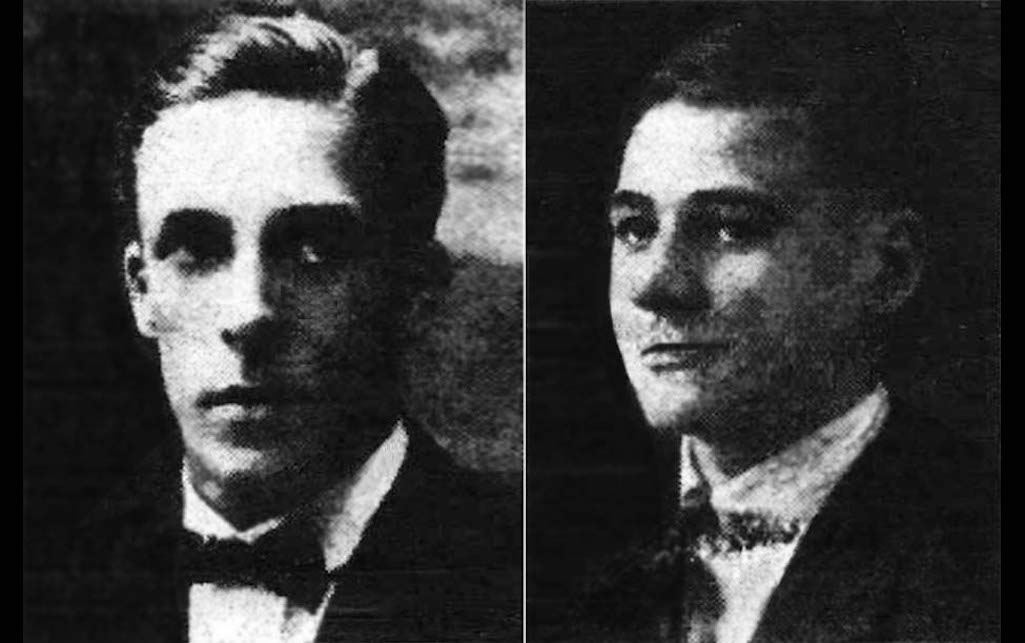

Left: Ralph Barber; Right: Joseph Stanley who drowned at Lea Green - contributed by Jo Bailey

Ralph Barber and Joseph Stanley who drowned in a Lea Green reservoir

Ralph Barber and Joseph Stanley

Artificial respiration was attempted for twenty minutes on the body of Joseph Stanley but he failed to revive. P.C. Derby made several dives into the water searching for Barber’s body but as it was so muddy and dangerous, he was forced to give up. At the pair’s inquest at St Helens Town Hall, coroner Samuel Brighouse told Joseph Stanley’s father Edward - a daywageman at Sutton Manor Colliery - that he would always have the memory that his son had lost his life bravely going to the rescue of a drowning man.

These examples are typical of the many deaths in Sutton’s waterways through accidental drowning while swimming. Warm weather, ignoring of danger warnings, tales of heroism and in some cases swimming while drunk, were often factors revealed at inquests. These days with youngsters not venturing out as much and with many alternative leisure and sporting activities, along with a lesser number of dangerous ponds and reservoirs, plus water safety education campaigns, the numbers of such fatalities have thankfully been greatly reduced.

Appendix: When The Dead Went To The Pub! – Coroners Inquests in Sutton

Picture this strange old Sutton scene. Crowded inside a dingy room within the Locomotive Inn is Coroner Samuel Brighouse, at least 12 male jurors, some witnesses and an uncovered dead body on a table! It does seem bizarre today for inquests to have been conducted in pubs, along with the deceased. However, it was the norm throughout the nineteenth century and this scene was regularly repeated.The Locomotive was located on the corner of Ellamsbridge Road and Peckers Hill Road and was just one of a number of Sutton pubs where the circumstances and causes of tragedies was investigated. Historically referred to as inquisitions, inquests were also held in the Red Lion, Griffin Inn, Golden Cross and the Navigation Tavern, amongst others. The latter tended to specialise in the demise of those unfortunate enough to have fallen or jumped into the adjacent canal. Pubs were chosen as venues because there were few alternative meeting places capable of accommodating so many people. Snugs were ideal and with a hearth fire lit in winter, were nice and cosy.

The Locomotive Inn in Ellamsbridge Road in Sutton, St.Helens where inquests were often held

The Locomotive Inn in Sutton, St.Helens where inquests were often held

The Locomotive Inn in Sutton where inquests were quite often held

The inquest on seven-year-old Lily and three-year-old Agnes Walton who, as described above, perished within the Rolling Mill reservoir, was held in the Locomotive. What a harrowing experience it must have been as a juror, legally required to view their bodies. They usually received just a shilling (5p) for their trouble. However, it was considered an honour to be a juryman, of which a minimum of 12 and a maximum of 23 members were required.

Due to the small pool of suitable male candidates, there were many regulars and some developed an expertise in prodding the dead and asking questions of the living. Do bear in mind that in old Sutton, people had more exposure to the dead than today. Even children were taken to view laid out bodies in the parlours of houses to pay their respects. Everyone in the street would draw their curtains during the mourning period, as many older readers of this article will recall.

Coroner's juries did have some clout and could make written recommendations, known as ‘presentments'. They made one on May 21st 1861 when they called for an overbridge to be built in Sutton's ‘Pudding Bag' to 'protect the public from accident'. This was at the inquest on the death of William Crooks, which was held in the Golden Cross. The 67-year-old gateman, who manned a level crossing, had died near the pub just the day before when struck by a train.

Although verdicts such as accidental death were the norm, juries investigating a violent death could bring in a verdict of murder or manslaughter against a named perpetrator. This curious pre-judging of a future court case happened quite often when the jurors felt there was strong evidence against an individual. Sometimes the alleged killer was found not guilty when they were later tried at the assizes. This happened after carter Richard Phythian had been arrested at his sister's house at St.Helens Junction on January 2nd 1868. The jury investigating his wife's death at their home in Greenbank returned a verdict that Phythian had committed wilful murder, killing his wife Mary without provocation. However on March 27th at Liverpool Spring Assizes, the defendant was cleared of the murder charge.

Although many jurors (and witnesses) undertook their task with relish, there were some individuals who refused to participate. On August 29th 1855, William Davies from Sutton was fined ten shillings by a coroner for refusing to be on a jury investigating a Ditch Hillock man's death. On May 15th 1888 the coroner fined the matron of St.Helens Cottage Hospital 40 shillings for not attending an inquest held at the Griffin Inn. Annie Stocks said she refused to appear as a witness, because she objected to the hearing being held in an inn.

Then on January 19th 1891, Alfred Hardy, the landlord of the Boilermaker's Arms, was fined £2 for declining his invitation to attend. Hardy was also a coal miner, so probably didn't want to lose a day's pay. At an inquest on September 2nd 1895, a juror asked Coroner Samuel Brighouse (1849 - 1940) what the circumstances were under which a man could be exempted from serving on one of his juries. The sharp-witted coroner replied: “A man must either be a lunatic, an idiot, or insane, and if he likes to advance any of those three reasons then I always excuse him”.

Sir Samuel Brighouse - Courtesy of Lionel Taylor, Practice Manager, Brighouse Wolff, Solicitors, Ormskirk

Sir Samuel Brighouse - Courtesy Lionel Taylor, Brighouse Wolff, Ormskirk

Sir Samuel Brighouse (by Lionel Taylor)

Many safety improvements in pits were brought in through Brighouse's critical comments and in Sir James Sexton's autobiography published in 1935, the former MP for St.Helens (1918 - 31) wrote that "the miners of South-West Lancashire regard Sir Samuel Brighouse as one of their greatest champions". Sexton also commented how he had also been a "valuable friend" of the dockers and through Brighouse's assistance, dock accidents had been greatly reduced.

The smell from corpses at inquests must, at times, have been dreadful. They were usually held within 24 to 48 hours of death to minimise the decomposition and odour caused by putrefaction. In 1894 Coroner Brighouse bitterly complained about the compulsory and distasteful viewing of dead bodies at the start of inquests. This was in the case of a collier killed in the sawpit of Lea Green Colliery. When the coroner arrived he was informed by Sergeant Small that the jury were not able to view the body as "owing to the frightful stench, it had been screwed down in the coffin". The Birmingham Daily Post of July 30th 1894 described how Brighouse had reluctantly ordered that the coffin be unscrewed and had commented how the viewing of deceased persons should only have to be made when absolutely necessary:

At the inquiry, the Widnes works of the United Alkali Company and the St.Helens Co-op Society tried to claim the money, arguing that the sovereigns were the proceeds of robberies that they'd both had. However they couldn't substantiate their claims and the Coroner's jury ruled that the find was treasure trove and so the cash was handed to the Duchy of Lancaster with compensation for the finders. Brighouse's sense of humour came through during the proceedings. Emptying a pile of gold coins onto his desk, the coroner said to the jury "This is the body, gentlemen"!

Brighouse ruffled feathers from time to time and in one inquest held on July 31st 1933 an extraordinary message was conveyed to him by the police. Sergeant Garlick had asked St.Helens doctor Patrick J. O'Keefe to write a note for the coroner about the medical history of a deceased patient. Not only did he refuse but told the officer to tell Brighouse that he could "go to hell". The aged coroner responded by inviting the sergeant to inform the medical man that he would "decline to accede to his request".

On June 27th 1934, Samuel Brighouse, who was born in Lathom and educated at Ormskirk Grammar School, had a Knighthood conferred by King George V. On October 4th, he was in a party of dignitaries that welcomed Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald back home after three months in Canada. During the 1930s, he called for better mortuaries, as some were pitifully basic, as well as improvements in road safety. With the increasing popularity of motor cars, Brighouse found himself conducting many inquests into road deaths. In August 1935 he claimed that he could halve the number of road accidents if his own suggestions were enacted. These included "special places where pedestrians could cross with safety...when they were crossing I would have the road blocked against motor traffic". Pedestrian crossings, in other words.

The days have long gone since inquests were conducted in pubs. Towards the end of the 19th century, there was a call for them to be held in venues more appropriate to the solemnity of the occasion. An increasing number were held at St.Helens Town Hall, where in 1895 a mortuary had opened. This allowed the jurors to leave the jury room to inspect the deceased and then return to listen to witnesses. Other inquests were held in school or church buildings, although this didn't always go down well with Samuel Brighouse.

On December 27th 1904, he conducted two inquests in the United Methodist Free chapel in Marshalls Cross. The coroner complained that it was as "cold as death" and said that in future inquests in the district must be held in the public house, probably referring to the Bull & Dog nearby. He added that when inquests were held in pubs, there was "a nice fire and everything was comfortable". Dedicated courts are now employed for the purpose of conducting inquiries into the deceased and since 1927, coroner's juries have been sparingly used. Advances in science and medicine have also obviated the necessity of having dead bodies in coffins lounging around on tables.

Sir Samuel Brighouse was still coroner when he died in bed on January 15th 1940 at the age of 90. He had his diary and notebook open in front of him and his fountain pen in his hand. References to Coroner R. W. Brighouse (c.1876 - 1941) in St.Helens local newspaper reports of the 1930s, refer to Sir Samuel's son, Robert Wales. His career as a deputy coroner was overshadowed by his illustrious father and RW's obituary in the St.Helens Newspaper in June 1941 focused on his Dad's achievements, rather than his own. As well as conducting inquests, the pair ran a family legal practice that began in the 1870s in Ormskirk. My late mother worked for the firm as a secretary during the 1940s and Brighouse's solicitors of Ormskirk and Southport still exist.